An Integrated Cognitive Perspective of Travel Motivation and Repeated Travel Behaviour

Abstract

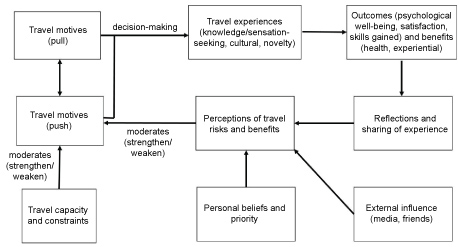

The present paper offers an integrated conceptual approach to the process model of travel motivation. It is important to understand why individuals are motivated to travel and how travel experiences benefit them. The proposed framework also hopes to understand travel constraints and perceived travel risks as their perceptions will influence repeated travel behaviour. The key factors associated with the process model of travel motivation include travel motives, travel experiences and sharing, as well as external influences on travel. Besides the push-pull factors as antecedents to travel, the process model of travel motivation also includes other factors such as external influences, personal beliefs and priority on perceived travel risks and benefits. Travelling has potential health benefits and outcomes that should be strongly encouraged. Furthermore, this paper attempts to offer some direction for future research in travel motivation.

Introduction

The topic of travel motivation has been increasingly important because tourism boosts the economy and tourists benefit from a vacation [1]. Travel is considered educational as it broadens one's perspective and mind. Besides educative outcomes, travel also benefits one's mental health and psychological well-being. It was found that individuals taking a vacation can reduce burnout and stress, as well as feel happier and healthier [2].

Recent studies in tourism have investigated and established travel motivations and travel behaviour in different types of travellers such as students, backpackers and seniors [1,3,4]. However, travel motivation is a dynamic and complex concept that varies from individual to individual. There is no integrated conceptual framework that focuses on travel motivation and repeated travel behaviour, as well as other related factors. Hence, the literature on these aspects in the general context is scarce.

Travel motivation is a dynamic process of travellers or tourist behaviour. Travel motivation is still considered in its infancy stage and this calls for more research in this area. The present paper aims to fill the research gap in the existing literature by proposing a process model of travel motivation and detailing the importance of each factor in repeated travel behaviour. For the purpose of this paper, travel behaviour is defined as the outbound travel or visitation of an outbound destination (i.e., across two countries). The key contribution of this paper is to establish a process model of travel motivation and how it can impact individual well-being.

First, the present paper began by providing an overview of the motivation theories related to travel, with inclusion of existing empirical literature. Second, it proposed a process model of travel motivation, understanding the underlying mechanism of individuals' repeated travel behaviour. Third, it explained the introduced key concepts in the model (see Figure 1) in each sub-section. Fourth, it explained repeated travel behaviour, linking back to the process model of travel motivation. Fifth, it included discussion and implications, identifying the gaps in existing research, contributions and related suggestions for future research directions. Finally, it ended with concluding remarks, focusing on cognitive and personal perspectives.

An Overview of Travel Motivation

Motivation has been an important topic in research studies, including education and tourism. It is viewed as the "driving force behind all actions" [5]. Motivation is thereby defined as the drive within individuals and the volition to act [6]. In this paper, travel motivation relates to a set of needs that impels an individual towards a certain travel activity or destination. For instance, the most common motives for travel overseas are knowledge, relaxation and novelty [2,7].

There are several theories in explaining the travel motivation of individuals such as push-pull effect [8,9] Ahola's escape-seeking approach [10], travel career approach to motivation [5], and theory of planned behaviour [11].

Push factors refer to the travellers' desires based on their inner needs and motivations, while pull factors include the attributes of a destination or an activity [12-14]. Push and pull motives are key concepts to explain travel motivation in a dynamic setting [15]. Recent empirical findings [16,17] supported the interaction between push and pull motives to visit a destination. For instance, Leong et al. [17] examined the impact of individual push motive on pull motive, indicating that individuals with the need for nostalgia are attracted to the historical and heritage pull attributes of a destination. This conceptual framework is widely accepted in measuring travellers' motivation, as it could explain the travellers' destination choices and responses to various destination attributes.

Escape-seeking approach [10] refers to the desire to leave the current place and obtain intrinsic rewards through travel to a new or particular destination. These two dimensions are similar to the push and pull factors, whereby push factor refers to "seek" and pull factor relates to "escape". The significant difference between escape-seeking approach and push-pull approach is, the "seeking" relates to intrinsic rewards or benefits, whereas the "pull" refers to the specific attractions of the destination that induces the traveller to go there.

Travel career ladder framework is a specialized concept of career's value and experience approach to tourism [5]. The underlying assumption of this travel career approach is, individual level of motivation increases when he or she accumulates travel experiences. The travel career ladder theory may predict individual travel motivational patterns. Some individuals' motivation may not progress, depending on contingency or limiting factors such as health and financial status. A recent study built on the travel career pattern approach to assess tourist motivation, uncovering the motivational patterns of Muslim tourists from Indonesia and Malaysia [18]. Thirteen push factors were identified and the participants ranked relationship, nature and novelty as top three important travel motives, while nostalgia and recognition (e.g., having known or recognized by others) were least important.

The theory of planned behaviour is influenced by the social environment [11]. Based on subjective norms, an individual may perceive what is important to him or her, resulting him or her to behave in a certain way. Likewise, an individual's beliefs and values may influence his or her perceived behavioral control [19]. Behavioral intention is expressive and displayed by attitudes. Attitudes, which are often resistant to change, have a powerful effect on thoughts and behaviours [2]. When deciding on a travel activity or destination, it requires deliberative processing of both internal and external information. Therefore, attitudes help to understand the dynamics behind travel motivation. According to Ajzen [11], the use of attitudes to predict behavioral intention is a unidimensional concept as it involves only affective component. As motivation relates to behavioral intention, travel motivation herein relates to the intention to travel.

Self-determination theory is also used to explain travel motivation [20]. Self-determination theory focuses on three basic psychological needs namely, autonomy, competence and relatedness. The fulfilment of these three needs will lead to intrinsically motivated behaviours and health benefits. Ahn and Janke [20] investigated the perceived motivations and benefits of senior participants (55-year-old and above) engaged in educational travel programs. Their findings showed that the educational travel programs promote health benefits, active engagement and socialization. This suggests that educational travel experiences are beneficial to elderly and could be an avenue for promoting healthy aging. Interestingly, this study also found that older females reported higher levels of intrinsic motivation than older males, due to the opportunities for self-expression and social engagement.

Most empirical studies focused on the factors and motives of travel in the context of tourism. Despite the abovementioned theories related to travel, there is no comprehensive theoretical framework because of the diverse human needs and challenges. Based on our existing knowledge, there is no literature that examines the "why" as well as the process of travel motivation and repeated travel behaviour.

There is still a gap in understanding the underlying mechanism or process of travel motivation and repeated travel behaviour. Specifically, why travel is considered 'addictive' to some individuals while meaningless to others and what are travellers seeking when they decide on a particular destination. This proposed framework of travel motivation adds to the understanding of travellers' perspectives that include the senior tourists, students and even backpackers. What is the underlying mechanism that explains repeated travel behaviour? Based on the review of over 20 recent empirical studies (2009-2018), the present paper proposes an integrated process model of travel motivation that is described in the next section (see Figure 1). This paper adapted the methodology for article search Chen and Petrick [21]. The search focused on primary research articles (i.e., empirical studies) from 2009 to 2018 in order to identify the research trends in travel motivation for the past decade. The literature review is also based on the key concepts in Figure 1.

Push factors or motives such as the search for knowledge or novel experiences may drive an individual to travel. Besides the push factors, individuals also seek a particular destination for various reasons or pull factors (e.g., UNESCO sites). Push factors often play a substantial role in the desire to travel overseas, especially in volunteer decision-making or volunteer tourism motivation [22]. The attraction to a particular destination could be due to knowledge or sensation (e.g., nostalgia), as well as culture or novelty. In a recent study [17], the need for nostalgia (i.e., destination choice push motive) affects a traveller's response to a specific destination attribute (i.e., pull motive). Consequently, travel experiences will have influences on one's psychological well-being, satisfaction as well as health and experiential benefits.

The involvement of a travel trip usually brings back memories of the places visited. After their travel expedition, individuals are likely to reflect on and share their experiences. Individuals could value such travel experiences when benefits are perceived. For instance, senior travellers who want to maintain or increase their cognitive functioning may be more interested in knowledge-seeking experiences and they will be involved in educational travel program [20]. They will also be more intrinsically motivated and engaged during their trip. Likewise, if they do not engage actively during the trip, they may not gain any skill or knowledge as an outcome. Hence, these travel experiences may support or thwart one's perceived travel benefits. Moreover, their perceived travel risks may impede their travel motives, discouraging them from travelling abroad. External influences such as media or friends may contribute to one's perceived travel risks and benefits. Personal beliefs and priority may also influence one's perception of travel risks and benefits. This in turn may support or undermine one's travel motives. Travel capacity and constraints may further moderate the travel motives. The abovementioned factors are further described in subsequent sections.

Travel Motives

Travel motive is defined as the reason that drives an individual to travel to a particular destination [16]. Travel motives can be categorized into push and pull factors. The former refers to intrinsic factors while the latter includes extrinsic factors. Intrinsic or push motives (e.g., experience or learn about local culture) evoke the need to travel while the extrinsic or pull motives are related to destination attributes (e.g., iconic landmark). Push factor such as nature-seeking and pull factor such as cultural attractions are the prevalent ones.

According to Xie and Ritchie [15], they identified the push and pull motives for the measure of travel motivation. They conducted factorial analyses on this travel motivation questionnaire, obtaining a two-factor push motive and a three-factor pull motive. The two factors for push motives include experiencing extreme activities and getting away, ranging from 3 to 4 items each. The three factors for pull motive include lodging and transport, cultural opportunities, as well as recreation and entertainment. Push motives include experiencing a new destination, learning something new and finding excitement. Pull motives include clean accommodation, convenient transportation, cultural attractions, and recreational activities or entertainment.

As there are numerous factors of travel motivation, the Table 1 consolidates the factors based on the empirical studies conducted over the last ten years.

The abovementioned factors of travel motivation drive an individual to travel to a particular destination, and experience a new or nostalgic environment. Travel motives are antecedents of travel experiences.

Travel Experiences

Pearce and Lee [5] identified four motivational dimensions within the travel career pattern. They are novelty-seeking, escape-seeking, relationship-seeking and self-development motives. Novelty-seeking motive is the main focus on travel motivation. It is defined as the pursuit of stimulation, whereas escape-seeking motive is viewed as the getaway from overstimulation. Relationship-seeking motive refers to the desire to establish social relationship through vacation travel. The social relationship includes kinships and permanent or temporary relationships. Self-development motive relates to personal growth and/or desire to learn. It also includes interaction with a host culture and the community, as well as meeting the locals there and experiencing different cultures. These four motivational dimensions also relate to the travel experiences in terms of what are the types of experiences that a traveller seeks. Travel experiences also include activities that are attractive and enjoyable, such as nature trekking, island hopping and many others. For instance, an individual may seek novelty experience in volcano trekking. He or she may plan for a volcano trekking in Japan (e.g., Mt. Fuji in Shizuoka) or Indonesia (e.g., Mt. Bromo in Surabaya).

The first three dimensions are likely to convey an emotional attachment. It is argued that affective attitude has an impact on novelty-seeking [23]. A tourist who has satisfying travel experience may foster emotional ties with the destination. Attitude which is considered an emotional construct includes pleasant, enjoyable and satisfying experiences [24]. Hence, a traveller seeking novelty will exhibit a strong effect on his or her attitude toward the particular destination. Self-development motives include knowledge- and cultural-seeking, which are considered rational. The knowledge-seeking experience may not exhibit a strong effect on one's attitude. However, the cultural-seeking experience is likely to have a strong influence on one's travel motivation. Zhang and Peng [6] found that the motivation of seeking cultural experiences became stronger when individuals accumulate their travel experiences.

Positive travel experiences can contribute to an individual health, relationships and well-being [21]. However, the positive effects of travel experiences may vary across individuals. This is due to individual perceived satisfaction and happiness during and after the vacation. Travellers who felt happy after the trip could be due to the positive incidents during their travel. However, this happiness might gradually diminish in the days after the vacation because of workload or job-related stress. Similarly, the family or friend relationship may strengthen after the vacation, leading to a stronger bond and travel satisfaction. This also links back to the motivation dimension of relationship-seeking and socialization benefit. It is also important to note that not everyone has positive travel experience and benefits from taking vacations. There are exceptional cases like travellers may get sick after their trip or suffer from jetlag due to time zone difference.

Generally, the antecedents of travel experiences such as the push or pull motives will influence the travellers' outcomes (e.g., satisfaction) and benefits (e.g., experiential). The outcomes and benefits of travel experience are discussed subsequently.

Outcomes and Benefits of Travel Experience

Travelling overseas can potentially relieve one's stress and contribute to health and psychological well-being. Recent empirical studies have demonstrated travel benefits in individuals such as happiness, health and relaxation [2,6]. Individuals perceive travel benefits differently, which in turn will influence their travel behaviours. Individuals are likely to travel when they perceive travel benefits from taking a vacation [25]. Therefore, individuals with perceived travel benefits will likely have positive effects of travel behaviour.

Travel benefits refer to the desirable outcomes from taking a vacation or pleasure trip [25]. The three desirable outcomes are relaxation, health and experiential benefits. Relaxation benefits include stress relief, getting away and recharge. Health benefits comprise better sleep, longevity and well-being. Finally, experiential benefits include novelty, knowledge, as well as experiencing nature and new cultures. Research findings from Chen and Petrick [25] showed that perceived relaxation, health and experiential benefits have positive effects on travel behaviour Prebensen et al. [26] revealed an additional benefit of socialization that includes meeting new people and participating in activities. Socialization is positively related to levels of involvement and satisfaction.

Based on recent literature review, the outcomes attributed to travel include knowledge and skills; self-confidence; adaptability; as well as attitude [27]. Experiential benefits include cognitive and affective learning, social and cultural awareness, transformative learning, as well as personal growth. Transformative learning refers to the change in viewpoints of a traveller during his or her travel, such as from "an ordinary resident" to "transformed homeowner" [28]. Hence, travel may bring about transformative experiences to the traveller.

Types of outcomes and benefits may be perceived to varying degrees across age groups. For instance, young adults are likely to recognize the importance of knowledge-seeking [29] and cultural learning [1]. On the other hand, socialization benefits were highly regarded by older travellers who were 55 years of age and above [20]. Older adults seemed to perceive active engagement in life as the most important benefit of travel.

Reflections and Sharing of Experience

Past travel experience can have an effect on an individual's attitude toward future travel or revisit intention [23]. For instance, if one's travel motive is to seek cultural experience in a specific destination and is not satisfied, this will likely negatively affect the revisit intention.

Satisfaction of travel is likely to strengthen the belief component of repeated travel behaviour. The motivation to travel is the act of satisfying one's psychological needs or desires relating to sensation-seeking or cultural experiences. Sensation-seeking includes satisfying curiosity or enjoying exotic food or shopping [4]. The sharing of travel experiences from individuals will reinforce their repeated travel behaviour in terms of perceived travel benefits or risks. One Asian study investigated the theory of planned behaviour in mainland Chinese travellers with the intention to revisit Hong Kong [23]. Their study found that travellers' satisfaction of past travel experience contributed to their revisit intention. In addition, travel motivation and past experience had a large combined effect on revisit intention. The travellers' intention to revisit Hong Kong may be associated with the quality of their past experience. The sustainable visitation interest may impact the country's tourism and economy. Through reflections and sharing, travellers are likely to capitalize on their choice by deciding to travel during times of economic progression. Similarly, they may reduce the visitation to a destination during times of economic downturn.

It is also important to accumulate travel experiences continuously and understand one's level of travel needs. By sharing travel experiences, it opens an avenue to yield better understanding of one's travel choice and demand. Prior travel experiences may increase or decrease one's propensity to travel. For instance, individuals have a higher propensity to travel or take future trips when they have a high level of travel involvement [30]. Involvement is defined as a personal relevance of the decision depicted by the amount of drive [26]. Hence, travel involvement is a motivational variable toward travel and decision-making with respect to travel. Prebensen et al. [26] found that motivation and involvement are linked to travellers' experience. Likewise, the perceived experience value of the destination and motivation could affect the level of involvement.

Perceived Travel Risks and Benefits

Travel risk is defined as potential injury or loss perceived by travellers during the process of travel intention and at the destination [31]. Jani [16] found that individuals who are motivated to travel because of cultural opportunities are likely to search for information to reduce the risks. Jani's findings also suggest that culture-based motives have a greater impact on risk travel information needs. It is interesting to investigate the relationship between motives and perceived travel risks, and how an individual changes his or her decision based on the contextual characteristics of the destination and available resources. For instance, the traveller may know that the geographical location of the country has natural catastrophes, yet he or she is still motivated to travel there. In this case, it could be the seeking of cultural experience or opportunities that he or she capitalizes on and is likely to search for information to deal with potential risks.

Travelling has physical, mental, and emotional benefits. Benefits include a sense of fulfilment and personal growth. Health benefits of travelling relate to travellers being happier and healthier. Perceived benefits refer to the individual's perception of travel benefits and how it may influence his or her decision to travel. For example, if an individual perceives the benefit of developing social and communication skills, it in turn strengthens his or her motive and motivation to travel. Then, this benefit actually developed the skill in the process of travel. A recent study found that individuals with perceived travel benefits attach personal importance to travel and they are more likely to travel frequently [25]. Hence, perceived travel benefits have impact on the traveller's motive and travel behaviour.

External influences such as social media (e.g., Facebook, YouTube) impact an individual's perceived travel risk and benefits. Social media is becoming increasingly important in travel planning and behaviour. For instance, there is a strong correlation between social media level of influence on destination and accommodation choice [32]. Findings suggest that travellers were more likely to change holiday plans in terms of destination and accommodation selections when their perceived influence from social media on destination and accommodation choices increase. As the choice of destination is related to perceived travel risk and benefits, information from social media will decrease the uncertainty of a destination. Similarly, external influence such as friends' recommendations may reduce the perceived travel risks and increase perceived benefits. External influence such as friends or relatives by word-of-mouth information sources could also influence one's travel decision [33]. It is interesting to note that travellers with previous experience were less likely to rely on word-of-mouth sources of information.

Personal belief is "paramount in personal change because it provides motivation and incentive to overcome barriers to change and evokes feelings of empowerment to enact change" [34, p. 484]. Personal beliefs and priority may influence a traveller's perceived travel risks and benefits. For instance, individuals with a strong personal belief of intangible benefits such as improved health or happiness may place their priority on health and have a strong affiliation to travel. When travellers perceive travel risks, the psychological component of negative messages may counter their initial desire to travel and they may not travel.

Travel Capacity and Constraint

Capacity is defined as the ability of an individual to carry out a particular activity [35]. Travel capacity herein refers to the ability of travellers to visit the destination choice. Individuals with travel capacity include financial stability, physical ability, general and mental health.

Travel constraints refer to the reasons that limit or inhibit individuals from travelling to the destination choice. There are three key factors associated with travel constraints, namely intrapersonal, interpersonal and structural. First, intrapersonal constraints include personal attributes such as health, personal ability, interest and perceived travel risk. Second, interpersonal constraints refer to attributes such as the willingness of others to travel with the individual and finding a travel partner. Structural constraints refer to external and situational factors that inhibit tourists from visiting the particular destination. Examples of such factors include limited financial resources, lack of time and distance barriers as well as catastrophes, weather and poor economic conditions.

Travel constraints have negative effects on perceived travel benefits and importance of travelling [25]. General health and psychological status contribute to higher travel motivation [20]. Particularly in older adult travellers, their travel constraint is likely high when they do not have a fair health status. Changes in health status may affect one's travel motivation as he or she may perceive higher travel risk and uncertainty. In addition, the travel itinerary or program may not match the physical level of the elderly traveller.

Travel Behaviour

Travel behaviour herein can be defined as the act of visiting a destination, driven by travel motives. The destination choice intention is usually informed by the theory of planned behaviour [19]. Travellers may visit the same destination again for nostalgia or a new destination for novelty. Travel behaviour is likely influenced by prior travel experiences, external values or personal beliefs. It is therefore important to understand the dimensions of travel motivation and how these contribute to one's repeated travel behaviour.

The motive to travel usually involves the choice of destination and the process of the selection. This process of destination selection encompasses three stages, namely the initial consideration, late consideration and final decision [30]. The first stage includes the individual awareness that is usually based on previous travel experiences or passive information from external influence. The second stage involves the action or search for information of selected destinations. The final stage is when the choice of destination is made and the selected destination is deemed most desirable and feasible place of visit.

Travel behaviour can be measured by the frequencies and percentages of travel [16]. Other variables that can relate to travel behaviour include travel mode (e.g., package tour or independent), travel purpose (e.g., leisure or business) and length of stay (i.e., number of nights).

Besides motivation, travel behaviour and destination choice are also related to personality. For instance, the personality trait of interest in cultural experiences, is related to the travel propensity for adventure travellers [36]. This suggests that the travellers placed value of importance on cultural aspects of adventure travel.

Linking back to personal beliefs and priority in the process model of travel motivation (see Figure 1), personality may also interact with the environment to influence one's repeated travel behaviour.

Discussion and Implications

This paper presented an integrated conceptual framework of travel motivation, with a definitional clarity in the process variables and an inclusion of factors associated with repeated travel behaviour. The intention of this paper is to propose a process model of travel motivation that is related to one's travel intention and repeated travel behaviour. This conceptual paper makes a theoretical contribution to the fields of motivation and tourism. It is one of the first attempts to incorporate key concepts or factors into the study of travel motivation and behaviour. The integration of factors, which are the influences of travel intention and behaviour, may facilitate the understanding of travel motivation from psychological, cognitive and sociological perspectives. This conceptual paper also provided some direction for future research, examining the interactions between travel motives and repeated travel behaviour, as well as between travel motives and individual perceptions. From a practical standpoint, the present paper reviewed the push-pull motives and how they could influence individual repeated travel behaviour, contributing to potential health benefits and well-being.

Based on the abovementioned review of empirical findings, travel motivation is beneficial to an individual's personal growth and well-being. Besides the benefits of travel motivation, it is also important to understand how perceived travel constraints and travel risks could influence repeated travel behaviour. As travel motivation is dynamic, future research is needed to establish the underlying mechanism of repeated travel behaviour. Future research should also test the relationships among travel motives, travel outcomes and behavioral intention. Nevertheless, there are some key implications to consider for future studies.

The tourism market and demand may be volatile because tourist demands change across time and the demand to specific destinations also varies. The demand to specific destinations may not remain stable as it is dependent on the cycles of an economy. The volatility of travel demand is also dependent on socioeconomic forces and demographic factors [30]. For instance, personal traits of an individual such as age, income, gender, and education will influence the travel demand. Likewise, socioeconomic situational factors such as unemployment rate will affect the degree of volatility.

The travel motivation herein focused on the push and pull motives. Hedonic motivation such as fun and pleasure should be addressed, exploring the benefits of hedonic travel experience. Likewise, it is interesting to contextualize the push and pull motives for hedonic experience as well as to identify potential profiles of individual travel motivation and perceived travel benefits.

Taking a vacation can relieve one's job-related stress and contribute to mental health and well-being. This paper puts forth an integrated conceptual framework of travel motivation and repeated travel behaviour. However, it did not discuss about the perceptions of non-travellers and individuals who are not interested to travel despite the travel benefits. Considering the cost and other factors, future research should examine the underlying mechanism of individuals who are not interested to travel versus travellers. Finally, further work should review topics such as travel decision-making that warrant a comprehensive review.

Concluding Remarks

"The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page" - Saint Augustine.

Travel motivation relates to why we travel. We travel for a variety of reasons such as adventure, relaxation, self-discovery and learning about another culture. We value our travel experiences and travel motivates us. The present paper proposed an integrated conceptual framework of travel motivation, which is an important issue in the study of tourism and psychology. It adds a cognitive perspective of travel motivation: an understanding of the underlying mechanism that explains repeated travel behaviour. The intention to visit a particular destination is usually informed by the theory of planned behaviour. Besides the empirical evidence of travel benefits, travelling also has the potential to broaden one's mind and perspective. Despite the known benefits of travel, there are still constraints and perceived travel risks to be taken into consideration. Most importantly, travellers should embrace a mindset that travel experiences are invaluable and enriching.

In our perspective, travel motivation is inextricably linked to human relations as well (i.e., forging new friendships and/or strengthening current relationships). For us, one of our most cherished memories are from the times when we were travelling together. Not only were we able to try new activities (e.g., helmet seawalker dive at the Great Barrier Reef), we were also rewarded with a host of unforgettable experiences that would not have been possible in our home country. While it may not be easy to find a travel buddy who shares the same travel interests and style, having a travel companion has its advantages. On a tangible aspect, there will be cost-savings as accommodation and other trip expenses are shared. On an intangible aspect, we develop our interpersonal skills as we learn to be open, accepting and appreciative of each other's differences and presence. As we return from our trip, new friends and the sense of nostalgia undeniably become motives for our subsequent revisit intentions.

Nevertheless, even if we choose to travel alone, the experience will be equally precious as we learn to slow down the pace of our lives, listen to our inner voice and heighten our awareness of our immediate surroundings. Solo travel is one of the few occasions when we are able to make decisions fully based on our internal considerations and bear the consequences on our own. Consequently, this gives us an empowering sense of responsibility and independence. Moreover, as we recognize our minute presence in the world, we learn to think beyond ourselves, be more tolerant to others and empathetic to issues at large. For example, being close to the wonders of nature could prompt us to rethink about living a consumerist lifestyle at the expense of the environment, and urge us to make more prudent and considerate choices.

Travelling also has the potential to broaden our horizon as we immerse ourselves in a different culture, set of customs and practice. Our routine ways and thoughts are challenged as we step out of our comfort zone and leave ourselves vulnerable to many uncertainties in an unfamiliar context, particularly in communities which speak a different language from ours. Faced with novel situations or problems every day, we get to understand our inadequacies and that it is alright to make mistakes as part of a learning process. Shedding our reputation and usual responsibilities in a foreign land, we find travel to be a humbling and transformative experience. We are encouraged to learn about others as much as we are to learn about ourselves. It may be attributed to survival instincts, but travelling makes clear and sharpens our ability to adapt, change and grow with new perspectives.

Some may prefer a 'mainstream' travel itinerary or style such as visiting iconic landmarks and splurging on luxury recreation while others may prefer exploring paths lesser known to visitors in suburban or rural area s. Notwithstanding, we encourage one to diversify his or her travel experiences as much as possible for each motive and behaviour has its own unique benefits to offer. Travelling also provides an opportunity to remain active and curious, contributing to our overall physical and mental well-being. With proper precautions and preparations, perceived and actual risks can be minimized or even eliminated. Like life, travel is an enriching learning journey to be anticipated and enjoyed; experiences, both good and bad, are to be treasured as they will build on our individual identity.

References

- Khan MJ, Chelliah S, Ahmed S (2018) Intention to visit India among potential travelers: Role of travel motivation, perceived travel risks, and travel constraints. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1467358417751025.

- Chen CC, Petrick JF, Shahvali M (2016) Tourism experiences as a stress reliever: Examining the effects of tourism recovery experiences on life satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research 55: 150-160.

- Hsu CY, Lee WH, Chen WY (2017) How to catch their attention? Taiwanese flashpackers inferring their travel motivation from personal development and travel experience. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 22: 117-130.

- Lu J, Hung K, Wang L, et al. (2016) Do perceptions of time affect outbound-travel motivations and intention? An investigation among Chinese seniors. Tourism Management 53: 1-12.

- Pearce PL, Lee UI (2005) Developing the travel career approach to tourist motivation. Journal of Travel Research 43: 226-237.

- Zhang Y, Peng Y (2014) Understanding travel motivations of Chinese tourists visiting Cairns, Australia. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 21: 44-53.

- Chen CF, Wu CC (2009) How motivations, constraints, and demographic factors predict seniors. Asia Pacific Management Review 14: 301-312.

- Dann G M (1977) Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 4: 184-194.

- Dann GM (1981) Tourist motivation an appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research 8: 187-219.

- Ross ELD, Iso-Ahola SE (1991) Sightseeing tourists' motivation and satisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research 18: 226-237.

- Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179-211.

- Crompton J L (1979) Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research 6: 408-424.

- Iso-Ahola SE (1980) The social psychology of leisure and recreation. WC Brown Co Publishers.

- Song H, Bae SY (2018) Understanding the travel motivation and patterns of international students in Korea: Using the theory of travel career pattern. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 23: 133-145.

- Xie L, Ritchie BW (2018) The motivation, constraint, behavior relationship: A holistic approach for understanding international student leisure travelers. Journal of Vacation Marketing.

- Jani D (2018) Residents' perception of tourism impacts in Kilimanjaro: An integration of the Social Exchange Theory. Turizam: Medunarodni znanstveno-strucni casopis 66: 148-160.

- Leong AMW, Yeh SS, Hsiao YC, et al. (2015) Nostalgia as travel motivation and its impact on tourists' loyalty. Journal of Business Research 68: 81-86.

- Oktadiana H, Pearce PL, Pusiran AK, et al. (2017) Travel Career Patterns: The Motivations of Indonesian and Malaysian Muslim Tourists. Tourism Culture & Communication 17: 231-248.

- Li M, Cai L A (2012) The effects of personal values on travel motivation and behavioral intention. Journal of Travel Research 51: 473-487.

- Ahn YJ, Janke MC (2011) Motivations and benefits of the travel experiences of older adults. Educational Gerontology 37: 653-673.

- Chen CC, Petrick JF (2013) Health and wellness benefits of travel experiences: A literature review. Journal of Travel Research 52: 709-719.

- Grimm KE, Needham MD (2012) Moving beyond the "I" in motivation: Attributes and perceptions of conservation volunteer tourists. Journal of Travel Research 51: 488-501.

- Huang S, Hsu CH (2009) Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research 48: 29-44.

- Hsu CH, Cai LA, Li M (2010) Expectation, motivation, and attitude: A tourist behavioral model. Journal of Travel Research 49: 282-296.

- Chen CC, Petrick JF (2016) The roles of perceived travel benefits, importance, and constraints in predicting travel behavior. Journal of Travel Research 55: 509-522.

- Prebensen NK, Woo E, Chen JS, et al. (2012) Experience quality in the different phases of a tourist vacation: A case of northern Norway. Tourism Analysis 17: 617-627.

- Stone MJ, Petrick JF (2013) The educational benefits of travel experiences: A literature review. Journal of Travel Research 52: 731-744.

- Morgan AD (2010) Journeys into transformation: Travel to an "other" place as a vehicle for transformative learning. Journal of Transformative Education 8: 246-268.

- Mohsin A, Lengler J, Chaiya P (2017) Does travel interest mediate between motives and intention to travel? A case of young Asian travellers. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 31: 36-44.

- Wong IA, Law R, Zhao X (2017) When and where to travel? A longitudinal multilevel investigation on destination choice and demand. Journal of Travel Research 56: 868-880.

- Reisinger Y, Mavondo F (2005) Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of travel risk perception. Journal of Travel Research 43: 212-225.

- Fotis J, Buhalis D, Rossides N (2012) Social media use and impact during the holiday travel planning process. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 13-24.

- Murphy L, Mascardo G, Benckendorff P (2007) Exploring word‐of‐mouth influences on travel decisions: Friends and relatives vs. other travellers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 31: 517-527.

- Dewar DL, Plotnikoff RC, Morgan PJ, et al. (2013) Testing social-cognitive theory to explain physical activity change in adolescent girls from low-income communities. Res Q Exerc Sport 84: 483-491.

- Cambridge dictionary. (2018).

- Schneider PP, Vogt CA (2012) Applying the 3M model of personality and motivation to adventure travelers. Journal of Travel Research 51: 704-716.

Corresponding Author

Betsy Ng, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, 1 Nanyang Walk, Singapore 637616, Singapore.

Copyright

© 2018 Ng B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.