Retrospective Analysis of Systemic Corticosteroids for Alopecia Areata in Pediatric Patients

Abstract

Background

Therapy for alopecia areata (AA) in a pediatric patient population is challenging and controversial. Common treatments include a variety of topical or injected agents. Systemic steroid treatment in children is controversial due to concern of negative side effects. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of systemic corticosteroid therapy for the treatment of AA in pediatric patients.

Methods

This retrospective chart review included patients treated with standard courses of oral corticosteroids (3-week taper starting at 1 mg/kg) for AA who were managed by the Dermatology Section at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia between 2015 and 2018. The following data was extracted from patients' charts: Severity of disease measured by Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores for AA, treatment regimen, duration of treatment and number of steroid courses, side effects, age, gender, and weight percentiles. SALT scores and weight percentiles were recorded at pretreatment as well as at 3 months and 6 months after initiation of treatment. SALT scores, when available, were additionally recorded at 9, 12, and 15 months after initiation of treatment.

Results

82 pediatric subjects were included in the study. Subjects were grouped according to severity at pretreatment with systemic corticosteroids with < 50% SALT as mild and > 50% SALT as Severe. Subjects in the > 50% SALT score group followed at 5 intervals (pre-treatment, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months, 15 months) showed statistically-significant improvement/lowering of SALT scores, while subjects in the < 50% SALT group did not over the same time period. No serious adverse side effects were documented in any subjects treated. However, 67 patients of a total of 82 studied relapsed during the time intervals observed. The average time to relapse was 21.9 weeks after initiation of treatment (standard deviation: 16.76 weeks; range: 4.71 to 73.43 weeks; median: 15.43 weeks). Additionally, weight percentiles had a statistically significant increase from baseline.

Conclusion

Patients with baseline SALT scores ≥ 50 improved significantly after a course of systemic steroids but relapsed on average 4-5 months later with concomitant weight gain.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic disease in which T-cell mediated autoimmune processes cause non-scarring patchy hair loss [1]. The prevalence of AA has been estimated to be between 0.1 and 0.2% [2]. It has been previously reported that AA's lifetime incidence is approximately 1.7% worldwide, but more recent studies estimate it to be approximately 2.1% [3-5]. In the United States between the years 1990 and 2000, this amounted to 2.4 million office visits related to AA [6]. This autoimmune disease also increases the risk for depression and anxiety [3]. Other psychosocial impacts of AA include decreased self-esteem, difficulties with interpersonal relationships, phobias, paranoia, and an overall negative impact on quality of life [7-9].

Multiple studies evaluate the efficacy of systemic corticosteroid therapy in adults with AA; however, few assess safety and efficacy in children [10]. Given that the onset of AA occurs before the age of 20 for 40.2% of patients, there is a particular necessity for the investigation of treatment options in pediatric populations where there are limited systemic options [3,10].

The severity of AA can significantly vary between patients in terms of both number and size of patches of hair loss. In addition to patchy hair loss, AA can involve total loss of scalp hair only, known as alopecia totalis (AT), or can involve loss of all body hair, known as alopecia universalis (AU) [11]. Common treatments for AA include intralesional triamcinolone injections, topical agents including corticosteroids, minoxidil, irritants, and allergens, as well as ultraviolet light-based therapies, and systemic therapies including oral corticosteroids, methotrexate, biologics, and off-label agents such as JAK kinase inhibitors [12].

A recent retrospective study conducted on pediatric patients treated with IV methylprednisolone demonstrated that shorter disease duration, younger age of onset, and lower disease severity (AA vs. AT/AU) were associated with better response to treatment. However, this study only included 24 children, and among the 16 patients out of 24 who responded, 81% of them eventually relapsed at 9.5 ± 12 months after the last course; only 3 children reported side effects, and none of them were severe [13].

Another study with a larger sample size of 65 children in Serbia, involved administration of oral dexamethasone as well as clobetasol propionate 0.5% ointment. In this study 61.5% of all patients were deemed "good responders," meaning they had at least 50% hair regrowth. A higher percentage of good responders were in the mild AA group that lasted < 12 months. In this study, 16.9% of patients had relapses, defined by an increase in affected scalp surface area by at least 10%, during the treatment period, but no patients suffered severe side effects [14]. While there have been more studies regarding intravenous pulse-dosed corticosteroid therapy in pediatric alopecia areata patients, there are overall very few utilizing oral corticosteroid therapy [15] or include a specific regimen in additional to oral corticosteroids [16]. Additionally, these studies have relatively few subjects.

The use of corticosteroids in AA is controversial; some studies have reported that the desired therapeutic outcome is only temporary and hair loss continues after withdrawal of medication [17]. Although systemic corticosteroids are commonly prescribed for those with extensive AA, their use is often limited by the side effects, including hyperglycemia, weight gain, immunosuppression, dysmenorrhea, hypertension, and acneiform eruption and mood changes [18,19]. There are also arguments claiming that glucocorticoid use in pediatrics patients is linked to adverse growth and bone health, which is of particular concern to some practitioners and parents [20].

Here we look at 82 pediatric subjects with AA that were treated with 1-3 courses of systemic steroids in 3-week periods of time (1 mg/kg/day for one week, then 0.5 mg/kg/day for one week then 0.25 mg/kg/day for one week). We examine change in Severity of Alopecia Tool Score as well as time to relapse and secondary side effects.

Methods

With institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective chart review of pediatric patients at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia with a clinical diagnosis of AA, AT, or AU who were treated with prednisone or prednisolone between 2015 and 2018. Therapy for all enrolled subjects age 1-18 years of age consisted of oral steroids (1 mg/kg/day for one week then tapered over the next 2 weeks) often in combination with topical therapies and/or intra-lesional triamcinolone acetonide injections. Many patients received additional courses of corticosteroid treatment after the first three-week course, with varying amounts of time between treatment courses. We documented the following in the patients' charts: Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores at start of treatment as well as approximately 3 and 6 months after the start of treatment, steroid used, steroid dose, number of steroid courses, duration of treatment, patient weight percentiles at each visit, gender, and age. Improvement was measured by changing SALT scores. Reported side effects of treatment at each visit were also recorded. Side effects assessed were increased incidence of infection, gastrointestinal symptoms, mood lability/changes, sleep disturbance, change in level of activity, increased appetite, or acne and other rashes. Subjects were excluded for the following reasons: 1) Treatment did not occur during the time-frame being analyzed; 2) If they had AA and were using steroids, but the steroids were intended to treat conditions other than AA; 3) Failure to complete corticosteroid therapy as directed (one patient did not complete therapy due to a gastrointestinal illness); and 4) Lack of follow up or SALT scores. Relapse was defined by any increase in SALT score following any decrease in score, signifying worsening hair loss after a period of improvement.

Please operationally define relapse. Specifically, to what does it refer? For example, any increase of SALT score from one time-period to the next.

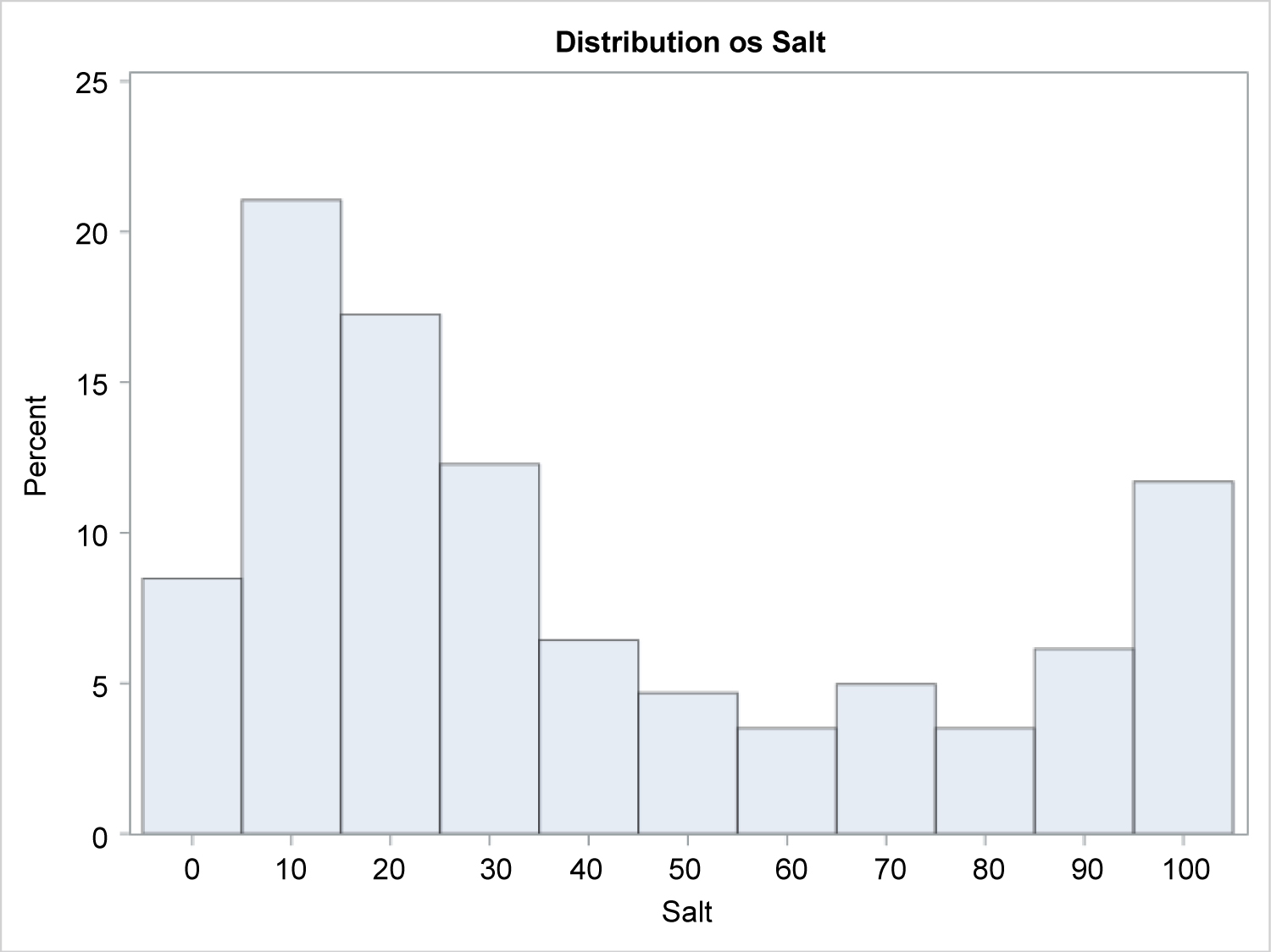

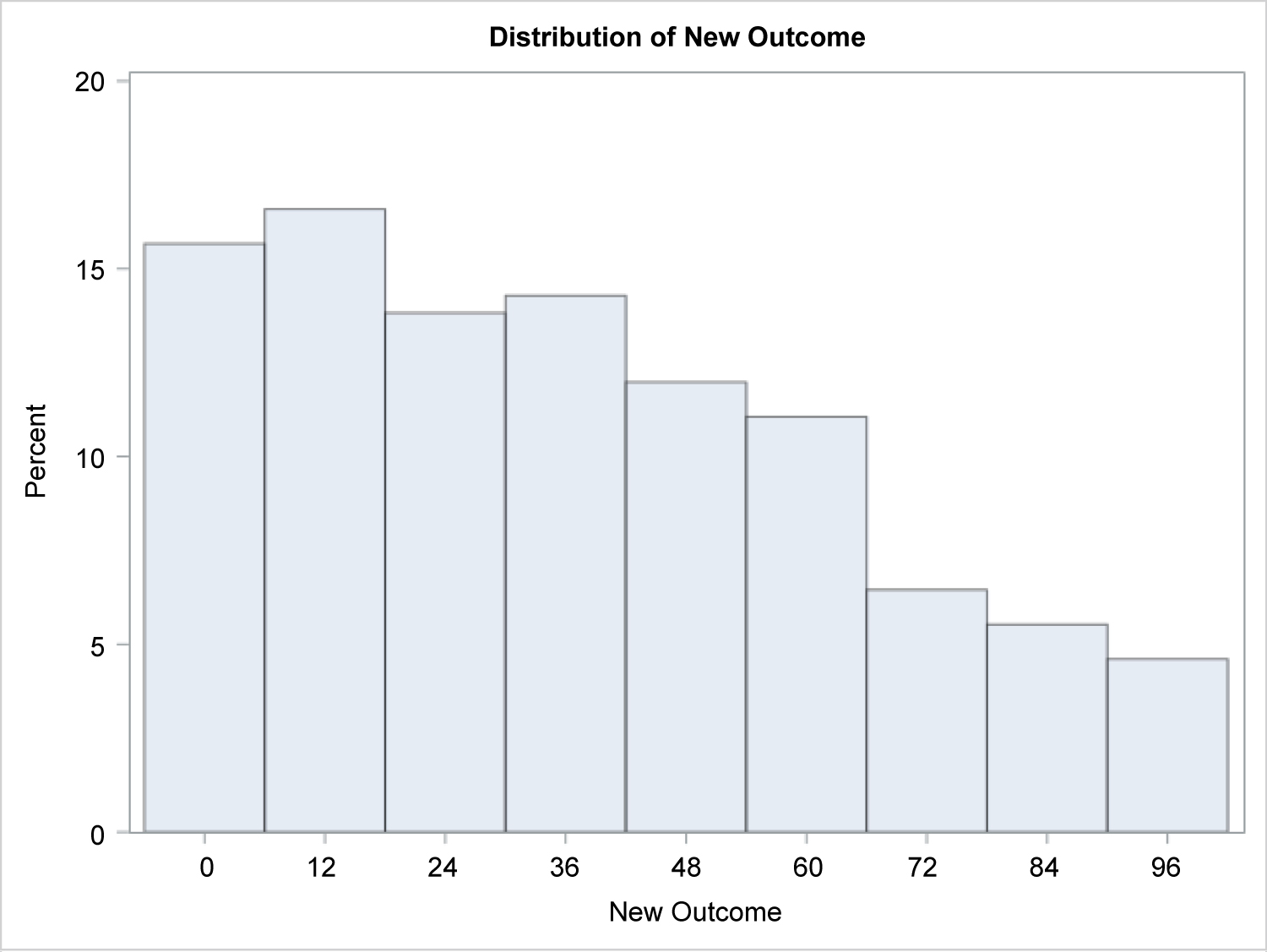

Statistical analysis was performed by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Biostatistics and Management Core. In analyzing treatment efficacy, SALT scores were the primary metric. Given the right skewed nature of the distribution of the outcome variable (i.e. SALT), a Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model using a Gamma link function was used to observe the association between SALT and Time. Repeated Measures Ordinal and Binary Logistic Regression Models were used to observe the differences in SALT scores over time.

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests were used to evaluate the difference in SALT scores from baseline versus each consecutive time point, using a Bonferroni p-value adjustment. After correction, significance was considered for p-value < 0.01.

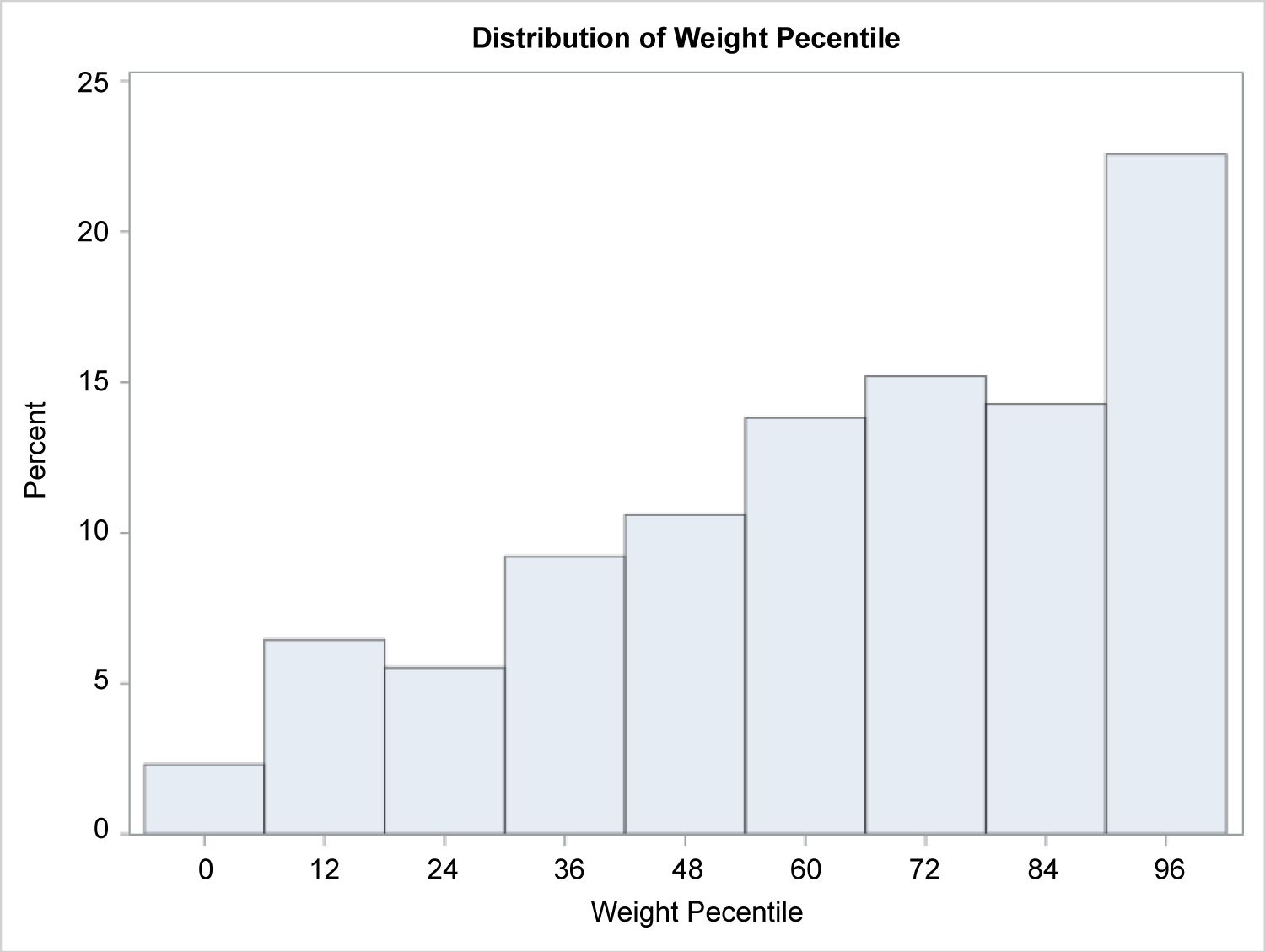

In addition, further analysis of toxicity was performed, principally based on patient weight percentile. Given the right-skewed nature of the distribution of the outcome variable (Weight Percentile), we first took a transformation of the outcome (100 - Weight Percentile) and ran a Generalized Linear Mixed Model using a Gamma link function to observe the association between transformed Weight Percentile and Time. Essentially, we are modeling decreasing weight percentiles at each time point.

Results

A total of 82 patients were included in this study (35 males and 47 females). There were 34 patients with Alopecia Areata (AA), 22 with ophiasis pattern alopecia areata (OP), 16 with Alopecia Totalis (AT), and 10 with Alopecia Universalis (AU). The mean age of diagnosis was 10 years (range of 1 to 17 years) and the mean time between corticosteroid courses was 18 weeks (Supplemental Table 1). Distribution of baseline SALT scores were found to have a right skew (Figure 1). Other therapies utilized to treat AA included topical corticosteroids, topical steroid-sparing agents, local irritants, and intralesional triamcinolone (Supplemental Table 2).

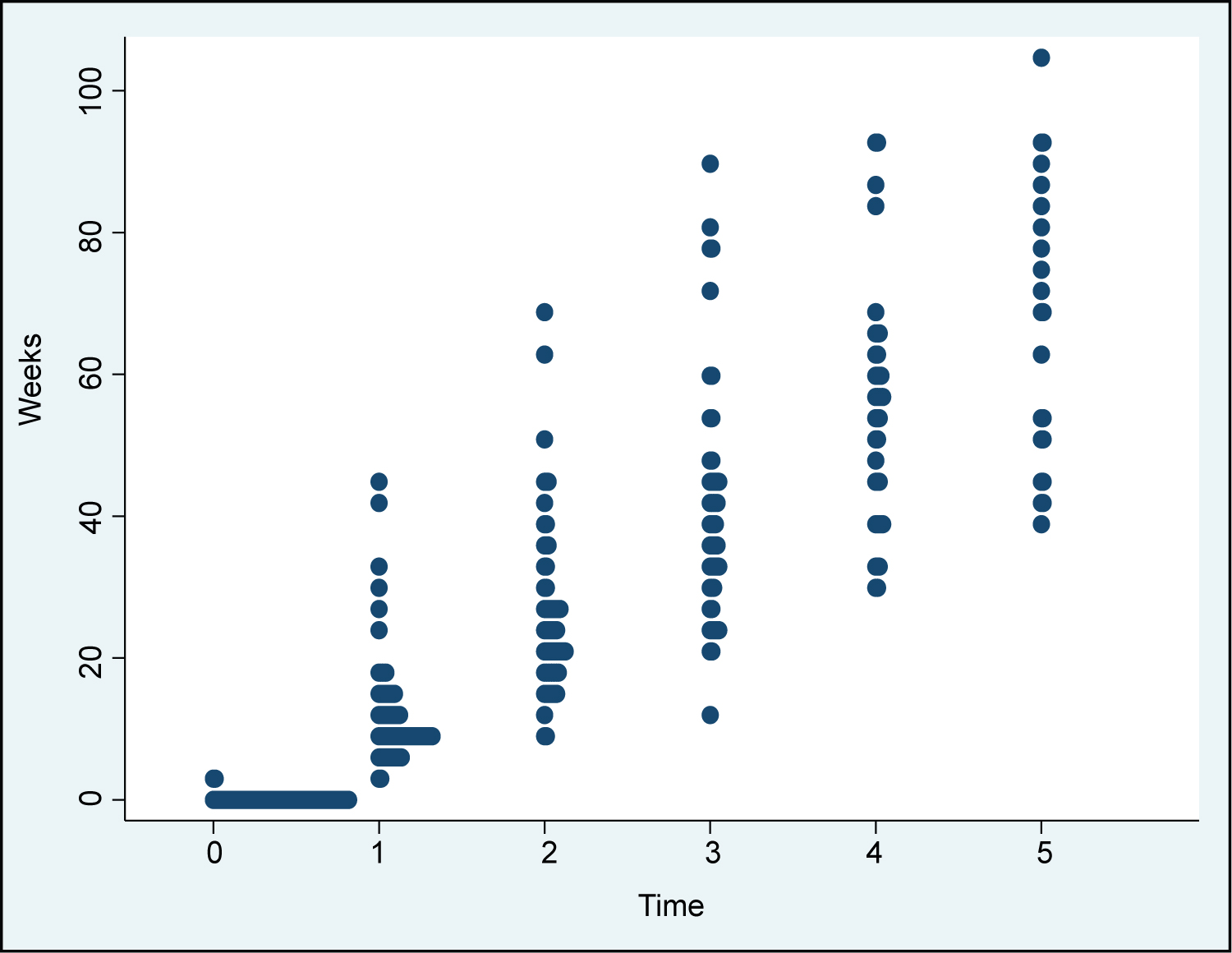

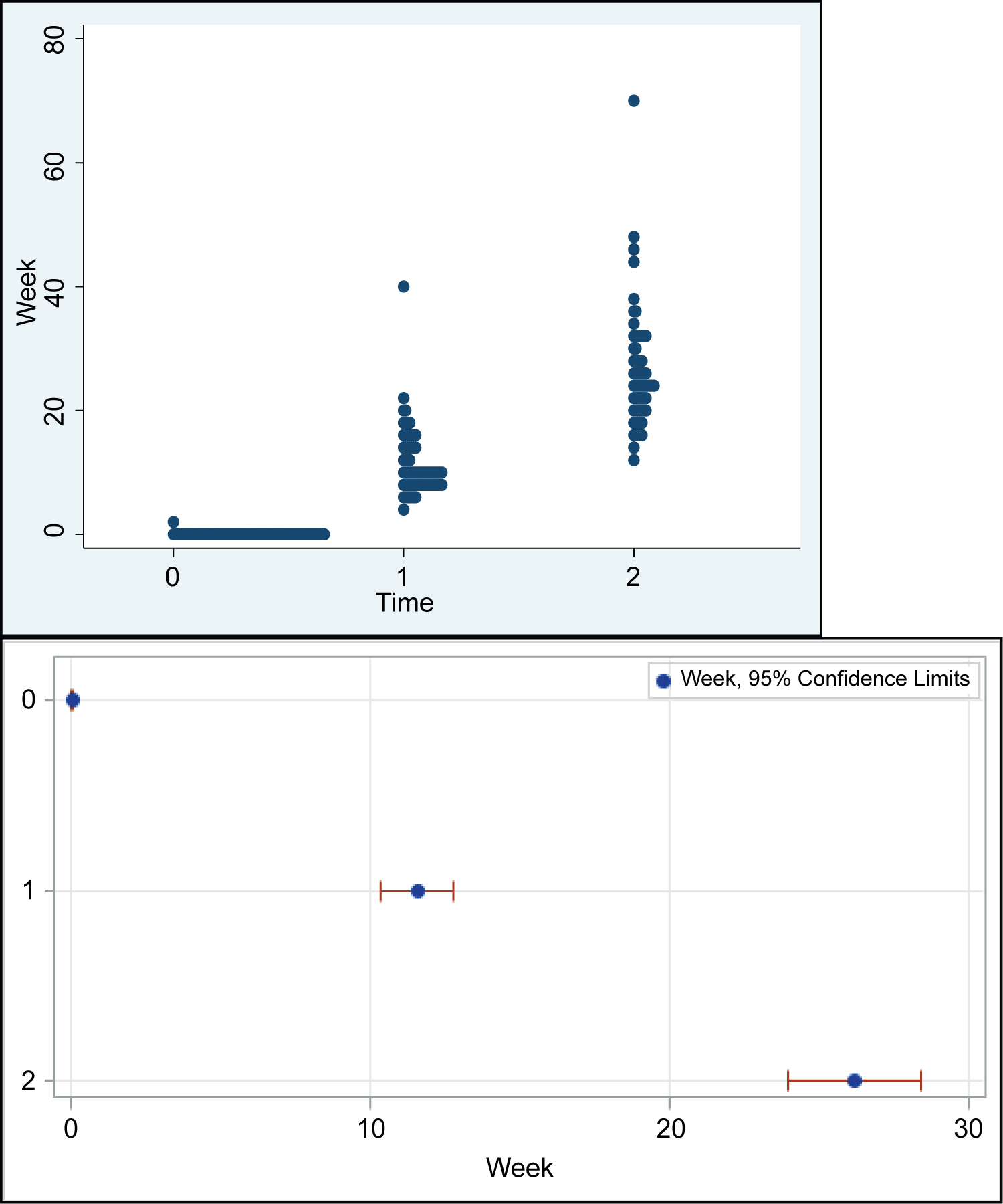

Because of the study's retrospective design, time points for follow-up measurement correspond to an approximate time of: 0, 12, 24, 36, 60, and 72 weeks, which have been annotated as time T0, T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5, respectively (with T0 being the time of diagnosis). Finalized Times points 0-5 do not necessarily correspond to the exact same gaps in time. The time points were selected to be distinct from each other, but there is some minor overlap. However, for the most part, we do not see a large overlap of average week, over time. The plot shows this, where the 95% only overlap slightly at the later time points (Supplemental Table 3).

For the full group of participants, regression of SALT scores over time using a generalized linear mixed model showed no statistically significant reduction in scores over the time period analyzed. Results of the generalized linear mixed model showed that there is no significant difference in SALT percentiles over time. Specifically, SALT percentiles at time 0 were not significantly different than SALT at any other time point (Supplemental Table 4 and Supplemental Table 5).

Subsequent, post hoc analyses failed to show a statistically significant reduction in SALT over time when measuring efficacy as either an ordinal (4 level) or binary response (Supplemental Table 6).

Neither ordinal nor binary logistic regression model methods showed significant differences in odds of increasing SALT scores or odds of high SALT scores, over time. In observing the odds ratios, there seems to be small increases in the odds, but there is probably not enough power in the data to detect these differences (Supplemental Table 6).

Results of the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests showed that SALT values were not significantly different from at any time point versus baseline values, using the p-value adjustment (Supplemental Table 7).

When all patients are combined into one group, scores at T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5 were not significantly lower than baseline. However, when grouping patients into two groups by baseline SALT scores (SALT = 50 cut-off), scores at T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5 were significantly lower than scores at T0 for SALT ≥ 50. Conversely, we observed negative changes in SALT score when patients' baseline measurements are < 50, though these results are not statistically significant (Table 1 and Table 2).

67 patients of a total of 82 studied relapsed during the time observed. The average time to relapse was 21.9 weeks with a standard deviation of 16.76 weeks, range of 4.71 to 73.43 weeks, and median of 15.43 weeks (Supplemental Table 8).

Results of the generalized linear mixed model showed that weight percentile is significantly different at baseline versus T1 (p < 0.0001) and T2 (p = 0.012; Table 3, Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Figure 3, Supplemental Figure 4, Supplemental Table 9 and Supplemental Table 10).

Discussion

The data for patients with baseline SALT scores ≥ 50 suggests they are more likely to improve, as measured by decreasing SALT score, over the course of their systemic steroid treatment than patients with baseline SALT score < 50. No patterns of improvement are seen when the two groups are combined, indicating an effect that may be unique to the group with baseline SALT ≥ 50. In this case, the group with baseline SALT > 50 is found to trend towards decrease in SALT score, and are statistically significant when looking at baseline vs. time 1,2, and 3, but was not statistically significant for baseline vs. time 4 and 5. This may be due to the fact that there are fewer subjects for which there were SALT scores recorded at time 4 and 5. Additionally, there may be relapse at this time.

Because of the lack of control group, the decreasing SALT scores cannot be confidently attributed to the systemic steroid treatment, as this change very may well be due to the natural course of the disease and "peaking" of AA flares. It is already a well-known phenomenon that patients chronically relapse, and that episodes of AA self-resolve. When comparing baseline SALT scores at any time point, no statistical differences were found. This may reflect an imprecise separation of patients into groups.

With regards to time points 0,1,2,3,4,5 at which weight percentiles were obtained, there was no major week or time overlap. Therefore, using the 0,1,2 time points are valid as they pertain to the time since start of treatment and are sufficient for comparing weight percentiles.

At baseline versus T1 and T2, weight percentile was statistically different. Specifically, weight percentile was higher at T1 and T2 than at baseline. This is consistent with the understanding that systemic steroid treatment leads to weight gain. Further studies documenting long-term effects in pediatric populations being treated with systemic corticosteroids for AA would help to elucidate how long these effects may last. Furthermore, as evidenced by the lack of patients in this study reporting serious adverse events requiring hospitalization or further treatment relating to the systemic corticosteroid therapy regimen, it appears safe to use during the course of treatment.

Mean time to relapse was found to be 21.9 weeks. A future thorough analysis should be conducted to better characterize the degree of relapse experienced, and whether the relapse of the AA was refractory to treatment. The timing of relapse recorded was limited to the time at which patients reported worsening and/or when the earliest appointment at which worsening was noted.

Limits to this study include small sample size, non-normal distribution of baseline SALT scores, and lack of control groups. A larger sample size would be necessary to potentially observe subtler benefits of systemic corticosteroid use. A good control group for future studies would account for age, gender, AA subtype, and additional topical therapies being used (nearly every patient in this study also was being treated with topical agents or locally injected steroids). Use of oral steroids may be a temporizing measure in children with SALT scores of > 50% at baseline but the effect is short with high likelihood of relapse and weight gain.

References

- Spano F, Donovan JC (2015) Alopecia areata: Part 1: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis. Can Fam Physician 61: 751-755.

- Safavi K (1992) Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol 128: 702.

- Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M (2015) Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: A systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 8: 397-403.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. (1995) Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Pro 70: 628-633.

- Mirzoyev SA, Schrum AG, Davis MDP, et al. (2014) Lifetime incidence risk of alopecia areata estimated at 2.1% by Rochester Epidemiology Project, 1990-2009. J Invest Dermatol 134: 1141-1142.

- McMichael AJ, Pearce DJ, Wasserman D, et al. (2007) Alopecia in the United States: Outpatient utilization and common prescribing patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol 57: S49-51.

- Tucker P (2009) Bald is beautiful?: The psychosocial impact of alopecia areata. J Health Psychol 14: 142-151.

- Rencz F, Gulácsi L, Péntek M, et al. (2016) Alopecia areata and health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 175: 561-571.

- Titeca G, Goudetsidis L, Francq B, et al. (2020) ‘The psychosocial burden of alopecia areata and androgenetica’: A cross-sectional multicentre study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 34: 406-411.

- Luggen P, Hunziker T (2008) High-dose intravenous corticosteroid pulse therapy in alopecia areata: Own experience compared with the literature. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology: JDDG 6: 375-378.

- Pratt CH, King LE Jr, Messenger AG, et al. (2017) Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers 3: 17011.

- Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E (2017) The changing landscape of alopecia areata: The therapeutic paradigm. Adv Ther 34: 1594-1609.

- Friedland R, Tal R, Lapidoth M, et al. (2013) Pulse corticosteroid therapy for alopecia areata in children: A retrospective study. Dermatology 227: 37-44.

- Lalosevic J, Gajic-Veljic M, Bonaci-Nikolic B, et al. (2015) Combined oral pulse and topical corticosteroid therapy for severe alopecia areata in children: a long-term follow-up study. Dermatol Ther 28: 309-317.

- Sharma VK, Muralidhar S (1998) Treatment of widespread alopecia areata in young patients with monthly oral corticosteroid pulse. Pediatric Dermatology 15: 313-317.

- Dey V (2016) Combination treatment of extensive and recalcitrant alopecia areata with oral and topical steroids with topical minoxidil: An open-label study of efficacy and safety in pediatric patients. Indian Journal of Paediatric Dermatology 17: 173-178.

- Brzezinska-Wcislo L, Bergler-Czop B, Wcislo-Dziadecka D, et al. (2014) New aspects of the treatment of alopecia areata. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 31: 262-265.

- Alsantali A (2011) Alopecia areata: A new treatment plan. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 4: 107-115.

- Aljebab F, Choonara I, Conroy S (2017) Systematic review of the toxicity of long-course oral corticosteroids in children. PloS one 12: e0170259.

- Mushtaq T, Ahmed SF (2002) The impact of corticosteroids on growth and bone health. Arch Dis Child 87: 93-96.

Corresponding Author

Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; Division of General Pediatrics, Section of Dermatology, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, 3401 Civic Center Blvd, Wood Center 3rd Floor Dermatology 3335, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

Copyright

© 2020 Tamazian S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.