Decision-Making as a Self-Organizing Process

Abstract

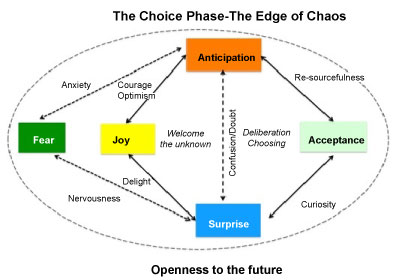

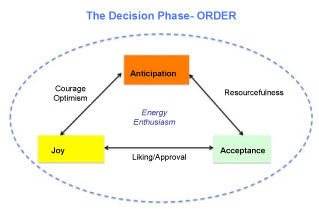

In this article, we present the analysis of the process of decision-making by applying the main concepts of complexity science linked with the theories of emotions. Decision-making in our personal or immediate social life concerns our future and involves surprises, uncertainty, and complexity. This is why complexity science, and especially the idea of self-organization is the most suitable for studying this unpredictable and surprising phenomenon. We propose that the process of decision-making in human life goes through three phases: The will phase, the choice phase, and the decision phase. Primary emotions of surprise and anticipation and self-organizing patterns of emotions such as curiosity, attraction, doubt, optimism, resourcefulness, open-mindedness, enjoyment of unknown, and enthusiasm play a significant role in this process. In the discussion, the process of decision-making from the perspective of metacognition is included.

Keywords

Decision-making, Self-organization, Emotions, Bifurcation, Complexity, Far-from-equilibrium, Metacognition

Introduction

In this article, we present the analysis of the process of decision-making by applying the idea of self-organization linked with the theories of emotions. Self-organization involves the spontaneous emergence of new states, patterns, and behaviours in an open, nonlinear, and complex system. External stimuli, such as unexpected events, challenging situations, artistic experiences, interpersonal relationships, and stimulating ideas, evoke in individuals a variety of emotions, which become a source of instabilities and fluctuations. They activate the internal processes and consequently trigger phase transitions or bifurcations that generates new patterns of behaviour. Therefore, we propose that the self-organizing mechanism represents the process of decision-making in human life. The decision-making process, especially for difficult and life-changing decision is a complex process.

To illustrate the process of decision-making we use one of the author's decisions described in her book Feeling Life [1]. We examine what basic emotions and then patterns of emotions are involved in decision-making and what is their role in this process. Based on this analysis, we present a conceptual model of the decision-making process, which contains three phases: 1) The will phase, characterized by a state of far-from-equilibrium in which the will emerges; 2) The choice phase, characterized by a complex state in which the choice is made, and finally 3) The decision phase, characterized by a dynamic order from which a final decision emerges.

In the first part of this article, the idea of self-organization, the theories of emotions, and the review the literature regarding the role of emotions in the process of decision-making are introduced. In the second part of this article, the detailed analysis of the process of decision-making by applying theories of emotions with the idea of self-organization is presented. Finally, the process of decision making from the metacognition perspective is discussed.

Self-Organization

Self-organization is not a single theory or a conceptual model; it is rather an idea that explains the process of the spontaneous emergence of new structures and new forms of behaviour in open, nonlinear, and complex systems. Lately, the idea of self-organization has been introduced to developmental psychology, especially to the emotion-cognition relations [2-6], personality development [7,8], adolescent development and creativity [9-12] and brain development [12,13].

The external environment preconditions the changes in the system and becomes a source of instabilities and critical fluctuations, which activate the internal processes. In a far-from-equilibrium state, the rapid flow of energy through feedback loops links its components into more ordered patterns. Ilya Prigogine introduced the concept of dissipative structures [15-17]. Such structures, to maintain their existence, must interact with their environment continually by keeping the flow of energy into and out of the system. Ilya Prigogine, in his book, Order out of Chaos wrote, "At equilibrium, molecules behave as essentially independent entities; they ignore one another... However, non-equilibrium wakes them up and introduces a coherence quite foreign to equilibrium" [17]. This is the concept of "order through fluctuations".

This global reorganization occurs at bifurcation points or phase transformation where old patterns break down and new one appear. At bifurcation point, the system "hesitates" between different directions of change. Even little fluctuations in the system can combine through the positive feedback loop, becoming strong enough to shatter the pre-existing organization. At this point, the disorganized system either disintegrates into chaos or leaps to a new, higher order of organization.

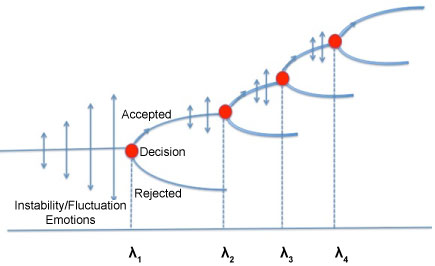

When we think of ourselves as nonlinear, dynamic, open systems, bifurcation points can be viewed as special events along the flow of our lives during which we make decisions to influence our future possibilities (see Figure 1).

Psychological bifurcations are the rapid transformations of sensory, perceptual, cognitive, and affective experiences that may radically alter our lifestyles. They appear in the process of learning, in creativity, in motivational states, in brain activity, in developmental stages, in the development [18]. Here are some examples of psychological bifurcation points: a) "Aha!" moment, or insight experiences, when a rapid perceptual or cognitive restructuring takes place in the context of working on a difficult problem; b) Moments when we experience overwhelming emotional transformations (e.g., falling in love); c) The moment when "of body" information rises to our attention (e.g., feeling of hunger) [19].

In complex systems, information about the result of a change flows through the loop of positive and negative feedback. Positive feedback pushes the system to change. More change leads to exponential growth whereas less change leads to decline. Sometimes, positive feedback drives a system to explode, spiral of out of control, or totally block all of its activities. For example, in psychological systems, emotions are dynamic processes of change. They act as positive feedback loops by amplifying cognitive activities. Negative feedback keeps things in check and regulates the stability of the system. In psychological systems, cognition plays the role of negative feedback by controlling and regulating emotional processes.

Self-organizing systems become more ordered and more complex over time. Two dimensions-differentiation and connection characterize the complexity of the system. Differentiation refers to a variety of different components behaving in different ways and leads to disorder. Connection, on the other hand, defines the links between the components of the systems and leads to order. Complexity arises when both of these dimensions are present. It can be said that complexity is situated between order and disorder, when the system finds itself at the "edge of chaos" [20]. At this state, the system is displaying intelligent behaviour in adapting to environmental stimuli. A complex system is capable of change, adaptation, and growth [11,12].

Emotions

Emotions can be understood as flows of energy that links our organism with the external world. They signal a need to make changes in our lives, assign a value to what is meaningful and important to our wellbeing, increase our awareness and influence our imagination. In some critical external conditions, evoked emotions create a far-from-equilibrium in our mental state. In this state, we become more aware of our situation and more attentive and focused on our problems. Therefore, we become active participants and sensitive observers of the ongoing processes of our experiences.

Emotions are dynamic and complex processes. They usually appear as the interactive patterns of emotional states rather than single entities. An emotional system is highly sensitive to changes in the internal and external environments. A concrete situation activates a discrete emotion that organizes and motivates behaviour. The activated emotion, depending on the context of its situation recruits other emotion. In effect, a coherent pattern of interacting emotions emerges through the process of self-organization [2]. The concept of emotional patterns as a source of multiple and dynamically interrelated motivational conditions increases understanding of event-emotion-action sequences [2,21].

Many emotion theories proposed a patterning of emotions such as affective-cognitive structures by Izard [2,22,23], emotion schemas by Izard [24], emotional interpretations by Lewis [3-5,7] secondary and tertiary emotions by Plutchik [25,26] and TenHouten [27], and developmental dynamisms by Dąbrowski [28-32]. These emotional patterns provide alternatives and an increased capacity to deal with complex and challenging problems [2]. They become a natural outcome of emotion and cognition, increase in number and complexity with development, and involve higher order cognition and complex appraisals development [2,24,28,29,31,32].

Ultimately, emotional experiences depend on how we perceive and evaluate our situation and the surrounding environment. In other words, we can understand emotions as adaptive functions that guide attention to the most relevant aspects of the environment, and of emotional appraisals as monitoring and interpreting events in order to determine their significance to the self [3].

Aaron Ben-Ze'ev [33], in his book, The Subtlety of Emotions, discusses the intentional dimension of emotions. He considers intentionality as a relation of "being about something" that involves our cognitive ability to help us separate ourselves from surrounding stimuli in order to create meaningful subject-object relationships. He proposes that the intentional dimension of emotions can be divided into three components-the cognitive, evaluative, and motivational. The cognitive component consists of information about any given circumstances; the evaluative assesses the personal significance of this information; and the motivational addresses our readiness to act.

Similarly, Nico Frijda [34] proposes that emotional experience is a complex phenomenon, and is a combination of experience of the world with a particular situational meaning structure (appraisal awareness), experience of affect, experience of a state of action readiness, and experience of arousal. Emotions are aroused when some event is being appraised. Appraisal means that some event obtains affective value. Appraisal of an object or event strongly depends upon the appraising individual: Upon his or her current concerns, his or her goals, sensitivities, interest, and values. The information mostly just happens to emerge from one's interactions with the environment. Appraisal and action readiness form a sequence that represents the core of any emotional reaction.

Frijda introduced general rules of emotions: The law of situational meaning-emotions arise in response to patterns of information that represent the meaning of eliciting situations; the law of concern-emotions arise in response to event that are important to the individual's concerns; the law of apparent reality-emotions are elicited by events with meanings appraised as real, and their intensity corresponds to the degree to which this is the case; and the law of change-emotions are elicited not so much by presence of favourable or unfavourable conditions but by actual or expected changes in favourable or unfavourable conditions [34].

The Role of Emotions in Decision-Making

In this section, we introduce a review of the literature on the role of emotions in the process of decision-making.

The process of decision-making in our personal or immediate social lives concerns our future and involves a great deal of uncertainty and complexity. Making a good decision means selecting a response that will be beneficial for our wellbeing. But the process of decision making based on rationality is enormously time and energy consuming. Because of a limited capacity of working memory, we can lose track of our calculations and might choose incorrectly and later regret our decision [35]. A Portuguese-American neuroscientist and neurobiologist, Antonio Damasio [35,36] proposes that emotions play an essential role in decision-making. He argues that when we make a choice, a variety of mental images or thoughts regarding that choice appear and disappear continuously in consciousness. We also experience some feelings related to the choice. Damasio calls these thoughts and feelings "somatic markers" because they're signals coming from our body. He defines them as "a special instance of feelings generated from secondary emotions. Those emotions and feelings have been connected, by learning, to the predicted future outcomes of certain scenarios" [35]. Somatic markers may lead to the rejection of some options (negative somatic markers) or to the acceptance of other options (positive somatic markers). This is why somatic markers help in the selecting process of options by quickly detecting an appropriate scenario. But, we have to understand that somatic markers are acquired by our experiences and are the result of our interactions with the social and cultural worlds.

Similarly, Peters [37] and Pfister and Bohm [38] suggest that at the moment of judgment or decision process, we should consult our feelings because they act as information to guide our decision.

Peters [37] proposes three additional separable roles of emotion/affect. It can act as a spotlight focusing us on different information and then that information is used to guide further our decision. The affect-as-spotlight hypothesis predicts that decision-makers who have positive feelings about the event/situation will spend more time learning about it. Next, affect can motivate us to take action, and finally, affect acts as a common currency allowing us to compare and integrate good and bad feelings rather than attempting to make sense out of a multitude of conflicting logical reasons.

While Pfister and Bohm [38] propose a four-fold classification of emotions with respect to their functions in decision-making. They suggest the following emotional functions in decision making: 1) To provide information (useful for evaluation); 2) To enable rapid choices under time pressure (concerned with speed; 3) To direct the decisions maker's attention to relevant aspects of the situation (depends on how the situation is appraised); 4) To generate commitment in social decision making (to implement decisions in the long run).

However, Loewenstein and Lerner [39] distinguish two ways that emotions impact decision-making. One involves the expected emotions, which consist of predictions regarding the consequences of decisions and another involves the immediate emotions, which are actually experienced during the actual decision-making process. They propose that the essential role in decision-making involves immediate emotions that direct attention to important events, provide useful information about different courses of action, and generate the motivation necessary to implement a chosen course of action. While the main benefit of expected emotions is that they guide behaviours affecting the long-term consequences of one's actions.

The Process of Decision-Making

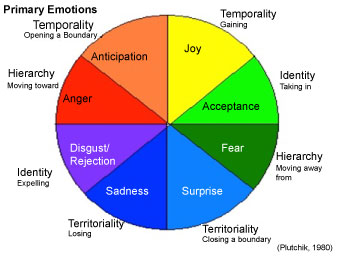

For the analysis of the process of decision-making, we combine the Plutchik's Psycho-Evolutionary Theory [25] with the idea of self-organization. For Plutchik emotions are adaptive reactions to the basic problems in life. He introduced eight primary emotions that are adaptive reactions to these basic problems of life. They come in pairs of opposites-one for adapting to positive situations (opportunities) and one for negative, problematic situations (obstacles) (see Figure 2).

Plutchik [25] proposed that all other emotions are derivative states occurring as combinations of the eight primary emotions. When two primary emotions are mixed, they produce secondary emotions, when three, tertiary emotions. Similar to color theory, the combining of these primary emotions produces a variety of emotions. They form patterns that stabilize over time and describe personality traits. Plutchik [25] noted that it was possible to find emotion names for each of the mixtures of two adjacent primaries, but for some mixtures of emotions that are more widely separated on the emotion circle, it was more difficult to find univocal names. He suggested that these mixtures of emotions are harder to imagine or less likely to be experienced than those that are closer on the emotion circle [25].

TenHouten [40] revised and extended Plutchik's theory by adding four additional emotions that combine the pair of opposite primary emotions into twenty- four secondary emotions, as defined by Plutchik [25]. There are twenty-eight secondary emotions that are in agreement with a combination formula (8!/2!6! = 28). He also defined seventeen tertiary emotions, but by using a combination formula (8!/3!5! = 56), fifty-six tertiary emotions could be produced.

The secondary and tertiary emotions emerge during the process of mental development, as primary emotions are combined into pairs and even triples [40]. There are three stages in the acquisition of complex emotions. In the first stage, primary emotions are developed, some of which are present at birth and the rest of which develop very early. In the second stage, the primary emotions are associated mentally to form the 28 secondary emotions. Beginning as early as age 7 years, children learn that a single event can cause two emotions. Over the next 3 or 4 years, they increase their understanding of co-occurring patterns of emotions [41]. And, in the third stage, tertiary emotions are formed, either by mental association of three primary emotions or by combining a secondary emotion and a primary emotion, which can be done in any of three ways [40]. Patterns of emotions involved in self-observation, self-evaluation and social comparisons tend to increase in middle and late childhood [42] and in early and middle adolescence [9,10,43]. For example, confusion can be expressed by anticipation and surprise, or embarrassment as a combination of fear with sadness.

In late adolescence and early adulthood, particular patterns of emotions experiences correspond with particular traits of personality. For example, a trait of ambition as a strong drive to accomplish one's goals can be understood as a combination of secondary emotion of pride (anger & joy) and anticipation. Or a sanguine trait of personality characterized by vitality, energy, and an abundance of ideas, can be expressed by resourcefulness (acceptance & anticipation) with joy [10,12].

The Event

To illustrate the process of decision-making, we present one of the decisions described by the author in the book Feeling Life.

"My attention was constantly directed toward the political situation in Poland and Eastern Europe. Because I cared deeply for what was going in Poland, news about the changes there evoked the emotions of surprise, delight, and curiosity" [1].

The news about political changes in Poland became the event that had a stimulating influence on her mental state. She recognized it as potential sources of meaning or even self-development.

Fogel [44] defines events as "the psychological experiences of real or actual entities such as objects, actions, feelings, or thoughts". He writes, that when we experience something as real, we are participating in the process by which orientations have coalesced into an awareness of events (p. 98).

Hermans and Hermans-Jansen [45] argue "the strategy of sharpening of the client's awareness of concrete and significant events may be very helpful at the start of the changing process. The success of these attempts is, however, highly dependent on the clients' capacity to direct their attention to these events and their openness to admit that these events are relevant to their self-exploration" (p.50).

The Will Phase

Surprise

Frijda [34] notes, that emotions arise in response to events that are important to the individuals (the Law of Situational Meaning) and to events that are taken to be real (the Law of Apparent Reality).

The event about political changes in Poland evoked in Laycraft [1] a variety of emotions. First of all, she became surprised. Surprise is activated by a change in environment and prepares individuals to deal effectively with new and sudden situations. It signals that more attention should be allocated to the situation and by recruiting other emotions contribute to change in their mental structure [22]. Tomkins [46] called surprise a "channel-clearing emotion". It clears the neural pathways for new activities. Charles worth [47] suggested that surprise increases arousal, instigates, and directs attention to the object or event eliciting the surprise. He wrote, "The surprise reaction can be viewed as consisting of a number of complex stimulus-producing responses that may serve to mediate, cue, arousal, instigate, "illuminate" and reinforce a variety of other responses that ultimately contribute to changes in existing cognitive structure" (p. 308). Therefore, surprise reorganizes and prepares consciousness for the possibility of different affective experiences and for different affective-perceptual processes.

The cognitive-psycho-evolutionary model of surprise designed by Meyer, et al. [48] considers surprise as an adaptive and evolutionary mechanism. A surprise-eliciting event triggers a series of processes. It starts with the appraisal of the event and as it exceeds some threshold value of unexpectedness, the feeling of surprise is evoked simultaneously with the interruption of the ongoing processing. The interruption of the ongoing activities permits focusing of attention on the surprising event and preparing the detailed analysis of this event. This process is characterized by an action delay.

In other words, surprise has two functions: 1) Informs the individual about the occurrence of mental disturbance and then 2) Provides a motivational stimulus for the analysis of the surprising event by evoking curiosity about its nature. Depending on the outcome of this analysis, the knowledge/beliefs may be extended or restructured. It is in agreement with Charles worth's [47] idea that surprise is a precondition for learning and cognitive development.

Delight

Events are not pleasant or unpleasant by themselves; they are appraised (p. 5) [34]. When the surprising event is appraised positively, surprise recruits joy and the secondary emotion of delight emerges but when is appraised negatively, surprise recruits sadness and disappointment emerges [25,40].

Delight, as "pleasant surprise", is an emotion that emerges through the conjunction of two kinds of social experiences: 1) An individual has gained some desired social outcome or resource that he/she was hoped for or expected (Poland becomes a democratic country- I hoped for it since my adolescence) and 2) That is also interpersonally gratifying (I believed that would bring changes for good in Poles' lives.).

Curiosity

As mentioned above, for the deeper analysis of the surprising events, curiosity is evoked. Curiosity is a secondary emotion, defined by a combination of surprise with acceptance [25,40]. This means that curiosity is the desire to voluntarily, intentionally, and pleasurably accept, or incorporate, that which is new or unexpected [40]. Curiosity is thus the willingness of an individual to expose him/herself to new information [49]. Frijda [34] wrote, "in curiosity the known world expands and offers new unknown areas at its frontiers" (p. 37).

In Berlyne's theory [50], curiosity is a state of arousal brought about by complex stimuli and uncertainty, leading to exploratory behaviour. The complexity of a stimulus, containing "novelty", "change", "surpriseingness", "incongruity", "complexity", "ambiguity", and "indistinctiveness" may increase arousal level and induce curiosity. In the case of "ambiguity" and "indistinctiveness", there is uncertainty due to a gap in available information. In some forms of "novelty" and "complexity", there is uncertainty about how a pattern should be categorized. In the case of "surprisingness" and "incongruity", there is a discrepancy between information embodied in expectations and information embodied in what is perceived (p. 245) [51].

The optimal level of arousal, where the individual becomes "curious", is just above the "tonus level" characterized by the moderate, pleasurable level of stimulation in which an individual functions most effectively. Day [52] describes the optimal level of arousal as one in which an individual enters a "Zone of Curiosity". With too much uncertainty, the individual becomes overwhelmed or anxious ("Zone of Anxiety"). With too little stimulation, on the other hand, the result is disinterest and demotivation often characterized by boredom. In either case, the individual is likely to withdraw from the exploratory behaviours before resolving his "conceptual conflict". By conceptual conflict, Berlyn [50,51] means conflict between incompatible attitudes or ideas evolved by a stimulus situation.

The tolerance and preference for arousal potential are different for different individuals. What one individual may find optimally arousing, another may find overwhelming or the other extreme, under-stimulating. Preference for arousal potential can vary from individual to individual and from occasion to occasion.

In the information-gap theory, Loewenstein [53] views curiosity as a feeling of deprivation, which occurs as an individual recognizes a gap in his/her knowledge and is motivated to obtain the missing information to reduce or eliminate the feeling of deprivation. The information gap is the difference between what one knows and what one wants to know, called the informational "reference point". Curiosity arises when one's informational reference point in a particular domain is above one's current level of knowledge. So, according to the information-gap perspective, a focus on missing information is a necessary condition for curiosity. Loewenstein [53] also proposed that as a person's knowledge of a particular domain increases, his/her awareness of information gaps in that knowledge will also increase, thus setting a necessary condition for curiosity to occur.

Curiosity has been conceptualized as a positive emotional-motivational system associated with the recognition, pursuit, and self-regulation of novelty and challenge [54]. Kashdan and his colleagues [54,55] designed the informational-processing model, in which curiosity leads to an increase in attention allocated to scan and orient oneself toward novel and challenging stimuli. This, in turn, leads to cognitive and behavioural explorations of stimuli, resulting in a flow-like engagement with these stimuli and activities, and ultimately to the integration of novel experiences by assimilation or accommodation [55].

Attraction

"Poland attracted me like a seductive lover. Where did its power come from? I asked myself why we were attracted to this difficult and challenging country, to its language and culture, to its rich but tragic history. The images of my parents and friends came to my mind" [1].

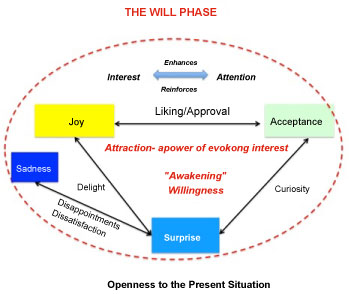

Surprise, joy, and acceptance interact with each other through positive feedback and self-organize themselves into a tertiary emotion of attraction [10] or seductiveness [40]. This emotional state can be described as a power of evoking interest in what is happening that increases the importance of images, memories, and ideas ("The images of my parents and friends came to my mind"). It makes them occupy a larger space in the field of the consciousness and remain in it for a longer time. It enhances and reinforces attention. Conversely, attention tends to increase interest through a positive feedback process ("I likened it to a black hole that sucked all my energy, thoughts, and feelings"). An individual becomes open and receptive not only to the external environment but also to internal environment ("I'd started to experience feelings of dissatisfaction with my life in Canada. It had become too stable and predictable"). She becomes an active participant and sensitive observer of ongoing processes of her experiences.

The will

The tertiary emotion of attraction combined with the emotion of dissatisfaction created a far-from-equilibrium state. Prigogine writes, "The remarkable feature is that when we move from equilibrium to far-from-equilibrium conditions, we move away from repetitive and the universal to the specific and the unique" (p.13) [17]. The far-from-equilibrium conditions relate to the critical amounts of energy and matter that flow and provide an opportunity to discover new and unique patterns of behaviour.

In our case, the new pattern of behaviour emerges in the form of the idea expressed by the will of returning to Poland.

"My attention was continually focused on Polish news. It was like an obsession that triggered the idea of returning to my native land" (p. 5) [1].

Thus the will can be understood as a bifurcation point that introduces a radical change in the functionality of the mental system and sets up a definite path for the process of decision-making.

In the book, The Act of Will, Robert Assagioli wrote, "The discovery of the will in oneself can change a man's self-awareness and his whole attitude toward himself, others, and the world. He perceives that he is a ‘living subject' endowed witsh the power to choose, to relate, to bring changes in his own personality, in others, in circumstances" [56].

While Karol Wojtyła in his philosophical work, The Acting Person, wrote, "Every authentically human "I will" is an act of self-determination". Then he continued, "When I will, I always desire something. Willing indicates a turn toward an object, and this turn determines its intentional nature" [57] (Figure 3).

In this phase, called the will phase, the decision-maker has experienced emotions, which had a direct impact on the process of decision-making by generating the will of returning to Poland (see Figure 3). Loewenstein and Lerner [39] call them immediate emotions. They transformed Laycraft's [1] predictable and stable world into the world in which she began paying attention to what is happening, desiring to take in and experience the situation, desiring to enlarge the range of interactions, and readiness to act.

The Choice Phase

Anticipation

"I was very much oriented to the future and anticipated it with a feeling of uncertainty. I reasoned that things might, or might not work out, and felt that the future would bring either joy and happiness or sadness and disappointment" (p. 6) [1].

The will of returning to Poland was only a part of a larger capacity for anticipation of the future events. Anticipation opens a boundary through exploration and an ability to plan. Anticipation can be understood as a feeling of excitement about something that is going to happen in the near future.

Anticipatory behaviour involves the concept of feed-forward, rather than feedback. The essence of a feed-forward system is that the present change of state is determined by an anticipated future state, derived in accordance with some internal model of the world (p. 20) [58]. In other words, and anticipatory system takes its decisions in the present according to forecasts about something that may eventually happen [59,60].

Hardy and Gres [61] view anticipation in the broader sense, as a capacity for a complex knowledge system to infer or expect the future state of a system, or future events. Anticipatory systems are able to plan a course of action or modify their internal organization. They are not single, monolithic type of process, but rather a set of different processes interrelated with each other. They include rationality-logic and scientific predictions, affects-feelings, hopes, desires, shared experiences, instincts, memory, beliefs-values, ethics, worldview, intentions-visions, will decisions, planning, active myths-personal myths, symbols, dreams, and intuition-inner feeling, harmony, vision, imagination, and emergent processes.

Goals -Values

Scheier, et al. [62] assume that people's behaviour is organized around the pursuit of goals that are values to them. While, for Schwartz [63] values are desirable, trans-situational goals, which vary in importance and serve as guiding principles in people lives. People then try to fit their behaviour to values they see as desirable and try to keep away from the values they see as undesirable (p. 32) [62].

"My objective was to bring joy, happiness, and satisfaction into my life by living and working in my own country, creating my own school, being with my parents, and connecting with my old friends" (p.6) [1].

In the above statement, the decision-maker expresses her goals-values and her emotions, which are not experienced as emotions per se at the time of decision-making, but they are rather expectations about emotions that will be experienced in the future. Their main role is to choose optimal actions that maximize positive emotions and minimize negative emotions [39].

Resourcefulness

For Klein, et al. [64] anticipatory thinking is the process of recognizing and preparing for future challenges and opportunities. They distinguish it from prediction because anticipatory thinking is functional - people are preparing themselves for future events, not simply predicting what might happen.

"I believed in my ability to apply the skills that would attain the goals I had created. I was confident in my capacity to survive in difficult and challenging conditions" (p. 7) [1].

A combination of anticipation with acceptance creates a secondary emotion of resourcefulness, which is defined as the ability to activate one's internal resources in any challenging situations.

Anxiety & Doubt & Ambivalence

But, the will of returning to Poland evoked in the decision-maker anxiety and doubt. Laycraft was concerned about her children who were approaching the difficult period of adolescence.

"How would they grow in these new conditions? Would their classmates accept them? I believed in their strength and resilience, but how would they feel there? So, the uncertainty of living in Poland made me feel anxious. I began to doubt our decision". (p. 4-5) [1].

Anxiety is a strong feeling of worry, nervousness, or unease about something with an uncertain outcome. So, anxiety is defined as a secondary emotion of fear and anticipation [25,40]. Thus, fear changes into anxiety as the focus of one's concern extends into the future (p. 98) [40].

Doubt is an expression of uncertainty and can be defined as a secondary emotion of surprise and anticipation. Doubt arises from two opposed tendencies-to simultaneously both believe and disbelieve what one has experienced (p. 108) [40]. But doubt acts as a sort of correcting mechanism-a means by which we test and appraise that what is meaningful for us, what is worth for us. Doubt can potentially play a creative role. Through doubt, we recognize our possibility of mistake in our thinking, and by applying our creative capacities we can correct our mistakes or avoid them.

Experienced emotions of anxiety and doubt arise from contemplating the expected consequences of the decision itself. Loewenstein and Lerner [39] call them anticipatory influences, which through a negative feedback loop can have some effect on immediate emotions and consequently on the decision itself.

In this phase of decision-making, the decision-maker experienced also a strong emotion of ambivalence that refers to the coexistence of contradictory attitudes or emotions toward an attitude object [40]. Ambivalence can be also understood as a conflict between the two sides of the attitudinal issues and to psychological discomfort resulting from conflicting beliefs or feelings [65]. In other words, ambivalence is the emotional manifestation of a conflict in which an individual both wants and does not want the same goal. Laycraft wanted to return to Poland but was nervous and afraid of the uncertainty of life in new Poland. She experienced a conflict between staying in Canada and returning to Poland. Her ambivalent feelings were both accepting and rejecting the decision of returning to Poland.

To reduce these feelings, Laycraft [1] had to make a mental effort by evaluating and then accepting the anticipated consequences of her decision.

"I reasoned that things might, or might not work out, and felt the future would bring either joy and happiness or sadness and disappointment" (p.6) [1].

Only by dialectical thinking that is characterized by accepting the opposed beliefs or opposed emotions, she was able to calm down and began to trust in her capacity to survive in difficult and challenging conditions. She came to believe that any encountered problems in her life could become an opportunity for new learning and development.

"I'd never been a fearful person; on the contrary, I was curious, courageous and open to new challenges. I'd always joked that I felt good in chaos and knew intuitively that in chaos, something interesting could happen" (p. 4) [1].

Optimism and Courage

"However, my optimism and courage were much stronger than my pessimism and drove me forward into unexpected possibilities that might involve a loss of the stability and security in Canada" (pp. 6-7) [1].

Anticipation and joy self-organizes into optimism and courage [25,40]. Optimism is positively related to favourable outcomes in life, to effective coping, satisfaction, and to a sense of wellbeing [40]. While, courage is the individual's capacity to overcome fear and anxiety, and to stand up for his or her core values [66].

Polish psychiatrist, Antoni Kepinski, in his book, Anxiety, wrote, "If we have the courage to visualize the darkness of the future and brighten it with a plan of action, then time becomes constructive. We feel we're a creator of our future. On the other hand, if we remain powerless in the face of the unknown, we become victimized and destroy any possibility of our future" (p. 6) [67].

In this case, optimism and courage can be understood, as immediate emotions arising from the traits of personality. When confronting an obstacle or threat, optimists tend to take a posture of confidence and are likely to assume the adversity can be handled successfully, whereas pessimists are more doubtful and hesitant and likely to anticipate disaster [62].

As we see from her statement, Laycraft [1] had chosen to live in the world of novelty, challenges and independent action and rejected the values of security, safety, and social order (Figure 4).

In this phase, called the choice phase, the negative feedback starts to influence the psychological systems, changes decrease, and stability slowly emerges. This condition allows Laycraft [1] to make a choice. Her choice emerges as a result of interaction between the anticipated emotions arising from contemplation of the consequences of the will and the emotions arising from personality traits (optimism versus pessimism) (see Figure 4).

Hypothetical choice

But, if we assume that Laycraft's pessimism, nervousness, anxiety, and doubt were stronger than her optimism, courage, confidence, and resourcefulness, we will see a different scenario of her life. Laycraft felt nervous because she knew that the idea of returning to Poland was a risky enterprise. She was uncertain about her ability to live and support her family in unknown and challenging conditions. Based on her previous experiences of living in Poland, Laycraft experienced also a strong feeling of anxiety. She thought about bad things that could happen in Poland. Therefore, Laycraft felt doubt, which choice would turn out best for her family and herself. She experienced her life in Poland, as well, her life in Canada then what options to choose. Because of the closeness of these two options, Laycraft had a really hard time to choose. Finally, after a prolonged time, she has chosen a security, safety, and stability instead of looking for changes, challenges and novelty in her life.

The Decision Phase

"In spite of my doubt, I felt enthusiastic and willing to experience something new" (p. 6) [1].

Enjoyment of the unknown

Emotions of surprise, joy, and anticipation self-organize into a tertiary emotion called enjoyment of the unknown [10]. This emotion expresses a readiness for surprise that means not being locked into a particular way of doing or thinking but appreciating some new and surprising possibilities. It means being ready and even happy to welcome the unknown and the unexpected.

Open-mindedness

Emotions of surprise, acceptance, and anticipation self-organize into a tertiary emotion called open-mindedness. Open-mindedness is an intellectual virtue that involves a willingness to take relevant evidence into account in revising former beliefs or values. It means being critically receptive to alternative possibilities [68].

Enthusiasm

Joy, anticipation, and acceptance create a strong emotion of enthusiasm. Enthusiasm helps us focus all our internal resources to reach high-value goals and enhance psychic energy and persist in goal pursuit [69].

In this phase, called the decision phase, the decision-maker stopped to struggle with herself, accepted the new reality, opened herself to new experiences, and fully embraced the unknown (see Figure 5).

A hypothetical decision

In the hypothetical scenario, when Laycraft has chosen to stay in Canada instead of returning to Poland, the main emotion was fear, which influenced her final decision. Fear had a functional value for her life. She was afraid that by moving to Poland, she could lose an interesting job, financial stability, a network of friendly people, material goods, and expose her children to unknown hardships. Therefore, her fear prevented Laycraft from getting into challenging and risky situations by moving to Poland. She made a final decision. She was staying in Canada. So, her doubt, anxiety, and nervousness disappeared.

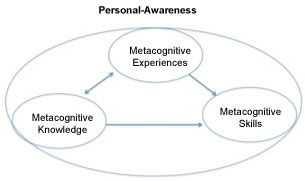

Decision-Making from the Metacognition Perspective

We look here at the process of decision-making from the metacognition perspective. Metacognition defined as cognition of cognition serves two basic functions, namely, the monitoring and control of cognition [70]. There are three facets of metacognition: Metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, and metacognitive skills [71].

Metacognitive knowledge (MK) in the context of decision-making is the kind of information a decision-maker posses about himself/herself including personal characteristics or traits, as well as information about goals, tasks, strategies, and cognitive functions such as attention and memory [70]. Metacognitive knowledge consists of an awareness and understanding that help individuals to make decisions effectively.

Metacognitive experiences (ME) are what the person is aware of and what she or he feels when coming across a task and processing the information to it. They take the form of metacognitive feelings, metacognitive judgments, and estimates [71]. MEs are likely to occur in situations that stimulate careful and highly conscious thinking. They can have very important effects on cognitive goals or tasks, metacognitive knowledge and cognitive actions and strategies. MEs can activate metacognitive skills [70].

Metacognitive skills refer to the deliberate use of strategies in order to control cognition such as orientation strategies, planning strategies, strategies for monitoring the execution of a planned action, and strategies for the evaluation of the outcome of task processing [72].

The process of decision-making can be expressed by the dynamical relationships between these three components of metacognition (see Figure 6).

The external event evoked in the person a variety of emotions/feelings, thoughts, and mental images (metacognitive experiences). Then these metacognitive experiences combined with the existing metacognitive knowledge caused her to select and used the cognitive strategies such as asking proper questions, getting new information, and appraising herself. The answer to her questions and the acquired information triggered additional metacognitive experiences (metacognitive feelings), which consequently activated new metacognitive knowledge (the will of returning to Poland). In the next phase, the process is similar. Activated metacognitive experiences (a variety of opposing feelings) combined with her increased metacognitive knowledge by selecting and using metacognitive skills such as the ability to effectively set goals and dialectical thinking allowed her to make a choice (a new metacognitive knowledge). And finally, the process continued in this same way until the final decision was made (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3).

As we have shown above, "metacognition is not cold (i.e. purely cognitive) as the nature of metacognitive knowledge would suggest; it is hot because affect is integrated with the monitoring of cognition in the case of metacognitive feelings" (p. 281) [71]. Metacognitive feelings, by activating metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive skills play a major role in the process of decision-making.

Summary

We have shown that decision-making is a self-organizing process, which begins with the meaningful event and then goes through three phases:

• The will phase that is characterized by the openness to the present situation, in which surprise plays the main role and by combining with joy and acceptance creates a condition of far-from-equilibrium for the will to emerge.

• The choice phase, situated between chaos and order, is characterized by the openness to the future, in which anticipation by combining with other emotions generates a condition for making the choice.

• The decision phase, in which the final decision emerges in a condition created by tertiary emotions expressing acceptance the new reality, openness to new experiences, and enthusiasm needed to remain in the effort for achieving the anticipated goal.

As we have shown, emotions play a significant role in the process of decision-making. By interacting with each other, they create a variety of emotional patterns, which emerge into a series of events, from the meaningful event into the will, then to the choice, and finally into the final decision. Emotion patterns and events can be understood as different aspects of awareness of self. Emotional patterns are connected with change and awareness of becoming, and events with stability and the awareness of being (p. 99) [44]. Therefore, the process of decision-making contains periods when being and becoming are present in a mutually stimulating dynamic equilibrium.

The emotions of surprise and anticipation play a special role in the process of decision-making. They both deal with the idea of territoriality [25]. Territory doesn't have to only be in the sense of a physical area, but can be our internal world, our rationality, affects, beliefs, intuition and so on. Understanding what is our "territory" allows us to anticipate what happens around us, how to adjust present behaviour in order to address future problems, what decisions to take in the present according to forecasts about something that may eventually happen. However, the emotion of surprise is the opposite of anticipation, as it is outside our scope of familiar "territory". Surprise prepares us to deal effectively with a new and sudden situation and directs our attention to it. Surprise starts a learning process in which our "territory" maybe extended or restructured. So, the process of decision-making can be understood as a transformation of consciousness to higher levels of awareness and understanding. The process of decision-making is similar to "transformative learning" [73,74], which "involves experiencing a deep structural shift in the basis premises of thought, feelings, and actions. It is a shift of consciousness that dramatically and permanently alters our way of being in the world" [75].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments. I would also like to thank Bogusia Gierus for reading the draft of this paper and her helpful comments.

References

- Laycraft KC (2014) Feeling life: Patterns of emotions. Aware Now Publishing, Victoria, BC.

- Izard CE, Ackerman BP, Schoff KM, et al. (2000) Self-organization of discrete emotions, emotion patterns, and emotion-cognition relations. In: MD Lewis, I Granic, Emotion, development, and self-organization: Dynamic systems approaches to emotional development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, US, 15-36.

- Lewis MD (1995) Cognition-emotion feedback and self-organization of developmental paths. Human Development 38: 71-102.

- Lewis MD (2000) The promise of dynamic systems approaches for an integrate account of human development. Child Dev 71: 36-43.

- Lewis MD (2000) Emotional self-organization at three time scales. In: MD Lewis, I Granic, Emotion, development, and self-organization. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, US, 37-69.

- Lewis MD, Granic I (1999) Self-organization of cognition-emotion interactions. In: T Dalgleish, M Power, Handbook of cognition and emotion. Wiley, West Sussex, England, 683-700.

- Lewis MD (1997) Personality self-organization: Cascading constraints on cognition-emotion interaction. In: A Fogel, MC Lyra, J Valsiner, Dynamics and indeterminism in developmental and social processes. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, 193-216.

- Lewis MD, Ferrari M (2005) Cognitive-emotional self-organization in personality development and personal identity. In: HA Bosma, ES Kunnen, Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction: Identity and emotion: Development through self-organization. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 177-198.

- Laycraft K (2011) Theory of positive disintegration as a model of adolescent development. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol Life Sci 15: 29-52.

- Laycraft KC (2012) The development of creativity. A study of creative adolescents and young adults. Doctoral dissertation, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

- Laycraft KC (2014) Toward the pattern models of creativity: Chaos, complexity, creativity. In: D Ambrose, B Sriraman, KM Pierce, A critique of creativity and complexity. Deconstructing clichés. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam, Boston, Taipei, 269-290.

- Laycraft KC (2014) Creativity as an order through emotions. A study of creative adolescents and young adults. Promontory Press, Victoria, BC.

- Lewis MD (2005) Bridging emotion theory and neurobiology through dynamic systems modeling. Behav Brain Sci 28: 169-245.

- Lewis MD (2005) Self-organizing individual differences in brain development. Developmental Review 25: 252-277.

- Prigogine I (1980) From being to becoming, time and complexity in the physical science. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Prigogine I (1997) The end of certainty. Time, chaos and the new laws of nature. The Free Press, New York, London,Toronto, Sydney, Singapore.

- Prigogine I, Stengers I (1984) Order out of chaos. Man's new dialogue with nature. Bantam Books, Toronto, New York, London, Sydney, 180-181.

- Abraham FD (1995) Introduction to dynamics: A basic language; a basic modeling strategy. In: FD Abraham, AR Gilgen, Chaos theory in psychology. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 31-49.

- Gilgen AR (1995) A search for bifurcations in the psychological domain. In: FD Abraham, AR Gilgen, Chaos theory in psychology, Westport, CT: Praeger, 139-144.

- Bertuglia, Vaio (2005) Nonlinearity, chaos, and complexity: The dynamics of natural and social systems. 287.

- Izard CE (2002) Translating emotion theory and research into preventive interventions. Psychological Bull 128: 796-824.

- Izard CE (1977) Human Emotions. Plenum Press, New York and London.

- Izard CE (1984) Emotion-cognition relationships and human development. In: CE Izard, J Kagan, RB Zajonc, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 17-37.

- Izard CE (2007) Basic emotions, natural kinds, emotion schemas, and a new paradigm. Perspect Psychol Sci 2: 260-280.

- Plutchik R (1980) Emotion: A psychoevolutionary synthesis. Harper & Row, New York.

- Plutchik R (1994) The psychology and biology of emotion. HarperCollins College Publishers, New York.

- TenHouten W D (2007) A general theory of emotions and social life. Routledge. Taylor & Francis Group, London, New York.

- Dąbrowski K (1973) The dynamics of concepts. Gryf Publications Ltd, London.

- Dąbrowski K (1996) Multilevelness of emotional and instinctive functions. Towarzystwo Naukowe, Lublin.

- Dąbrowski K, Kawczak A, Piechowski M (1970) Mental growth through positive disintegration. London: Gryf Publication Ltd.

- Dąbrowski K, Piechowski MM (1977) Theory of levels of emotional development. From primary integration to self-actualization. Volume 2, Dabor Science, New York.

- Dąbrowski K, Piechowski MM (1977) Theory of levels of emotional development Volume 1 - Multilevelness and positive disintegration. Dabor Science, New York.

- Ben-Ze'ev A (2000) The subtlety of emotions. A Bradford Book, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England.

- Frijda NH (2007) The laws of emotion. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey, London.

- Damasio A (1994) Descartes' error: Emotion, reason, and human brain. Penguin Books, London.

- Damasio A (2003) Looking for Spinoza. Joy, sorrow, and the feeling brain. A Harvest Book Harcourt Inc, Orlando, Austin, New York, San Diego, Toronto, London.

- Peters E (2006) The functions of affect in the construction of preferences. In: S Lichtenstein, P Slovic, The construction of preference. Cambridge University Press, New York, 454-463.

- Pfister H-R, Bohm G (2008) The multiplicity of emotions: A framework of emotional functions in decision making. Judgment and Decision Making 3: 5-17.

- Loewenstein G, Lerner JS (2003) The role of affect in decision making. In: RJ Davidson, KR Scherer, HH Goldsmith, Handbook of Affective Science. Oxford University Press, 619-642.

- Ten Houten WD (2009) A general theory of emotions and social life. New York: Routledge

- Harter S, Buddin BJ (1987) Children's understanding of the simultaneity of two emotions: A five-stage developmental acquisition sequence. Developmental Psychology 21: 388-399.

- Ruble DN, Flett GL (1988) Conflicting goals in self-evaluative information seeking: Developmental and ability level analyses. Child Dev 59: 97-106.

- Laycraft K (2009) Positive maladjustment as a transition from chaos to order. Roeper Review 31: 113-122.

- Fogel A (2001) A relational perspective on the development of self and emotion. In: HA Bosma, ES Kunnen, Identity and emotion. Development through self-organization. Cambridge University Press, 93-114.

- Hermans HJM, Hermans-Jense E (1995) Self-narratives: The construction of meaning in psychotherapy. The Guilford Press, New York, US.

- Tomkins SS (1962) Affect, imagery, consciousness: The Positive affects. Volume I, New York: Springer.

- Charlesworth WR (1969) The role of surprise in cognitive development. In: D Elkind, J Flavell, Studies in cognitive development. Oxford University Press, London, 257-317.

- Meyer WU, Reisenzein R, Schutzwohl A (1997) Toward a process analysis of emotions: The case of surprise. Motivation and Emotions 2: 251-274.

- Day HI, Langevin R, Maynes F, et al. (1972) Prior knowledge and desire for information. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science 4: 330-337.

- Berlyne DE (1960) McGraw-Hill series in psychology. Conflict, arousal, and curiosity. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, US.

- Berlyne DE (1965) Structure and direction in thinking. John Wiley, Oxford, England.

- Day HI (1982) Curiosity and the interested explorer. NSPI Journal, 19-22.

- Loewenstein G (1994) The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin 116: 75-98.

- Kashdan TB (2004) Curiosity. In: C Peterson, MEP Seligman, Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press, Washington, DC, 125-141.

- Kashdan TB, Rose P, Fincham FD (2004) Curiosity and exploration: Facilitating positive subjective experiences and personal growth opportunities. Journal of Personality Assessment 82: 291-305.

- Assagioli R (1992) The act of will. Arkana, Published by the Penguin Group.

- Wojtyla K (1979) The acting person. D. Reidel Publishing Company (Translated from the 1969 Polish edition Osoba i Czyn), Dordrecht, Holland, Boston, USA, London, England.

- Louie AH (2010) Robert Rosen's anticipatory systems. Foresight 12: 18-29.

- Poli R (2010) The many aspects of anticipation. Foresight 12: 7-17.

- Poli R (2010) An introduction to the ontology of anticipation. Futures 42: 769-776.

- Hardy C, Gres S (2004) Anticipation: Humans versus Machines, International Journal of Computing Anticipatory Systems (IJCAS), 1-15.

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW (2001) Optimism, pessimism, & psychological well-being. In: EC Chang, Optimism & pessimism: Implications for theory, research, & practice. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, 189-216.

- Schwartz SH (1992) Universals in the content and structure of value: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In: M Zanna, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Academic Press, NY, 25: 1-65.

- Klein G, Snowden D, Chew Lock Pin (2012) Anticipatory thinking. In: KL Mosier, UM Fisher, Informed by knowledge. Expert performance in complex situations. Taylor & Francis Group NY& London: Psychology Press, 235-246.

- Van Harreveld F, Van der Pligt J, De Liver YN (2009) The agony of ambivalence and ways to resolve it: Introducing the MAID model. Personality and Social Psychology Review 13: 45-61.

- Lachman VD (2007) Moral courage: A virtue in need of development? MedSurg Nursing Journal 16: 131-133.

- Kepinski A (2002) Lek (Anxiety). Krakow: Wydawnictwo Literackie (in Polish).

- Hare W (2012) Open-minded inquiry. Helping students assess their thinking.

- Poggi I (2007) Enthusiasm & its contagion: Nature & function. In: Paiva ACR, Prada R, Picard RW, Affective Computing & Intelligent Interaction. Lecture Notes of Computer Science, Sprnger, Berlin, Heidelberg, 4738.

- Flavell JH (1979) Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive developmental inquiry. American Psychologist 34: 906-911.

- Efklides A (2008) Metacognition: Defining its facets and levels of functioning in relation to self-regulation and co-regulation. European Psychologist 13: 277-287.

- Veenman MVJ, Elshout JJ (1999) Changes in the relations between cognitive and metacognitive skills during the acquisition of expertise. European Journal of Psychology of Education 14: 509-523.

- Mezirow J (1997) Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Direction for Adult & Continuing Education 74: 5-12.

- Mezirow J (2000) Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- O'Sullivan E, Morrell A, O'Connor M (2002) Expanding the boundaries of transformative learning: Essays on theory & praxis. New York: NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Corresponding Author

Krystyna C Laycraft, The Center for CHAOS Studies, P.O. Box 549, Nanton, Alberta, Canada.

Copyright

© 2019 Laycraft KC, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.