An Inquiry into Sexual Assault Experienced by Young Jamaicans during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic

Abstract

Introduction: The rate of sexual assaults remains high in Jamaica. This research inquires about the factors that lead to sexual assaults, particularly among young adults.

The objectives of the study are to:

1) To determine the levels of sexual assaults among young Jamaicans,

2) Assess where the cases of sexual assaults occur, and

3) Evaluate the gender disparity in sexual assaults among young Jamaicans.

Methods and materials: This study used a correlational research design conducted and by way of a web-based standardized survey, which consisted of twenty-five (25) closed-item questions. These questions aim to obtain demographic data, assessing the gender of the assaulted, where the incident took place, if it was reported, sexual activity, and the frequency of the same. Five hundred and six (506) Jamaicans ages 18 to 30 across the island participated in this study.

Findings: Thirty-six per cent of young Jamaicans have been sexually assaulted during the pandemic (females, 87.0%; males 11.4%; χ2 (3) = (39.275, P < 0.0001). One in every two of the sexually assaulted young female Jamaican has had penile penetration during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to nine in every 20 young male Jamaicans (χ2 (1) = 105.223, P < 0.0001). The majority of the cases occurred at home (13.8%) followed by at school (4.3%), and in a vehicle (4.2%). Of the 156 sexually assaulted respondents, the majority of them were assaulted by friend/family friend (38.5%, n = 60) followed by a family member (excluding father/stepfather, 25.6%, n = 40), a stranger (14.7%, n = 23), father/stepfather and taxi operators (4.5%, respectively). Seventy-six per cent of those who indicated reporting the abuse to someone were sexually assaulted compared to 95% of those who did not report the matter to anyone (χ2(1) = 15.109, P < 0.0001). Forty-six per cent of the respondents indicated that they have been threatened following the sexual encounter, 31.6% have been physically assaulted, and 52% stated that they informed someone of the sexual encounter.

Conclusion: Social isolation and lack lockdown have created a sexual pandemic as young Jamaicans have become targets for sexual predators in their homes. The reality is sexual assaults are occurring in an environment where victims are presumed to feel safe, and these cases are likely to go unreported. Policymakers, therefore, need to implement measures to address a pending public health crisis that may include sexually transmitted infections, post-traumatic stress disorder, and unwanted pregnancies.

Keywords

Sexual assault, Rape, Sexual violence, Young adults, Pandemic, Sexual predators

Introduction

Sexual assault is a crime that occurs when a person is pressured, coerced, or tricked into sexual acts against their will or without their consent [1-3]. Sexual assault takes into consideration several factors; including the kind of sexual encounter (whether it was noncontact, touch, penetrating or mere attempts) and the degree of force (unwanted versus consensual sexual experiences) [4,5]. The World Health Organization [6] refers to sexual violence as a public health concern, which means that the matter is more than unwanted sexual encounters or exploitation. In fact, WHO identified sexual assault or violence as "short- and long-term consequences on women's physical, mental, and sexual and reproductive health" and the matter equally extends to men.

In the article, "A discussion on sexual violence against girls and women in Jamaica" Smith, et al. [7] described Sexual violence in Jamaica as an endemic. Furthermore, Dunkley-Willis [8] opined that "SEXUAL predators [in Jamaica] have gone on a rampage since the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) restrictions started in March, assaulting a number of children who were forced to stay home after Government ordered school shut in the face of the pandemic." In addition, Bourne, et al. [9] using data from 1970-2013, found that "Over the studied period (i.e., 44 years), on average, 778 ± 465 people (95% CI: 626-931) were murdered in Jamaica compared to 1,062 ± 333 (95% CI: 952-1,171) who were raped or carnally abused" (p. 588). Nevertheless, this problem has not motivated the public into action with the same level of intensity as other types of violence inclusive of intentional homicide. It has not received the scholastic intensity and the communal investments it deserves [7]. The Statistical Institute of Jamaica [10] published that in 2019, the end of year population of young adults (ages of 15-29) was a total of 735,269 (females, 361,557; males, 373,691) (STATIN, 2021), which represents 26.9% of the population of the nation (young females ages 15-29 years constituted 13.2% of the end of year population compared to 13.7% for young males ages 15-29 years). Unfortunately, according to Elntib, et al. [11], "Rates of sexual assault remain high in Jamaica, although victims are often reluctant to report incidences to the police. Those cases which are reported by victims are investigated by the Jamaica Constabulary Force's Centre for Sexual Offences and Child Abuse [11].

The intent of this study is to assess and determine whether: Young adults are the ones being assaulted, females are more likely to be assaulted, sexual assaults occur in an environment where victims are presumed to feel safe, sexually assaulted are threatened or physically harmed and whether sexual assaults are likely to be reported.

Theoretical framework

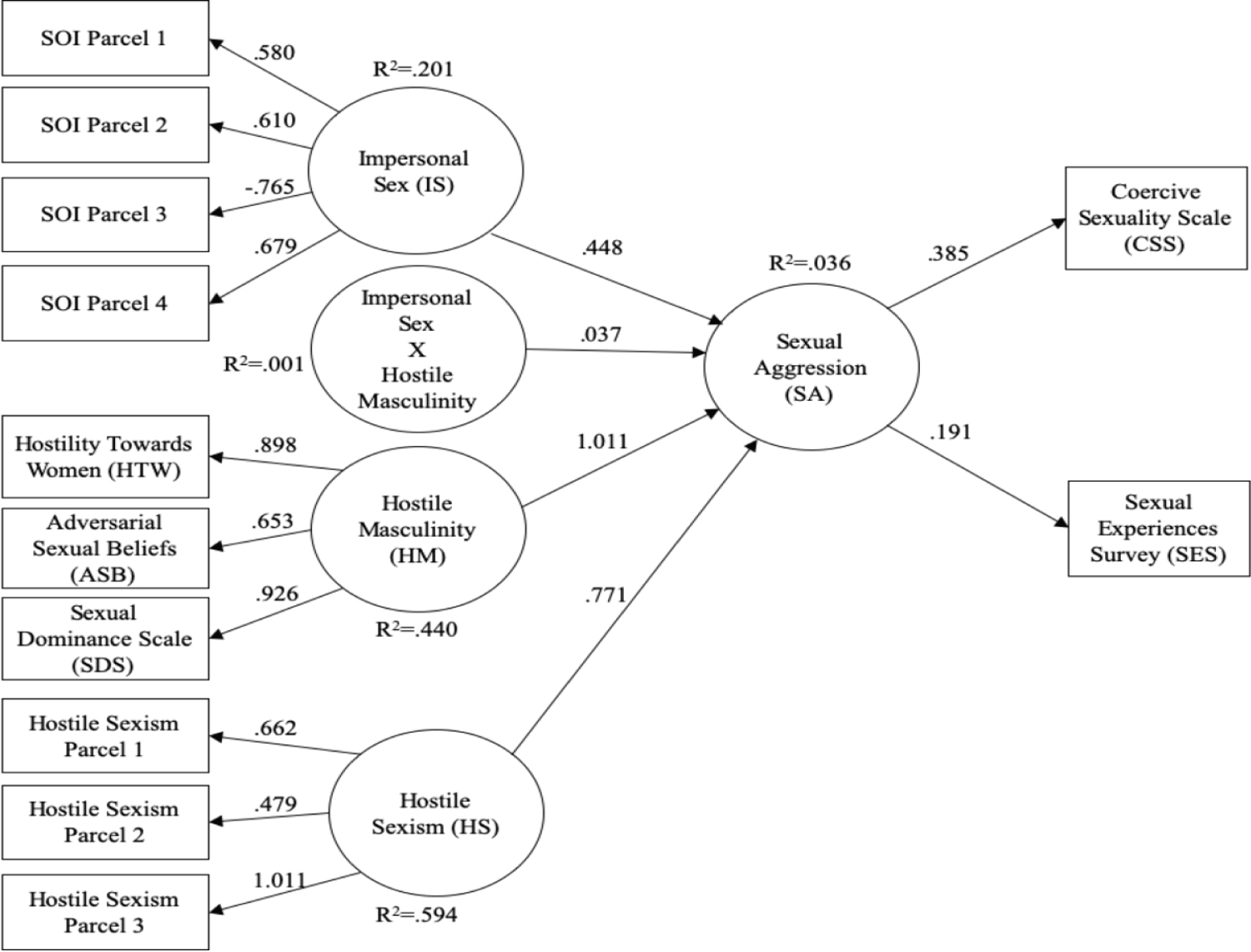

The Confluence Model is well promulgated in the literature to address factors that account for men's sexual penetration and sexual aggression against women. The factors are encapsulated into two areas- promiscuous-impersonal sex and hostile masculinity- merge to result in sexually aggressive behavior [12-15]. According to the Confluence Model, a desire for intimacy through sex and the development of long-term relationships or monogamous sexual activity is lacking. The relevance of sexual promiscuity to sexually aggressive behavior is related to evolutionary theory. In short, natural selection has created fundamentally different psychological mechanisms in the brains of women and men with regard to sex and intimacy, resulting in the male's preference for short-term over long-term mating patterns. If men are adapted for sexual performance in impersonal contexts, then a disinterested or unwilling partner may fail to inhibit or may even entice sexual aggression [13,14].

Hostile masculinity involves dominating and controlling personality traits, particularly in regard to women. According to Malamuth, et al.'s theory, it is in women's reproductive interest to withhold sex from insufficiently invested partners. Drawing on an earlier study that found that withholding sex angers men [14]. Malamuth and colleagues theorized that if a woman repeatedly withholds sex from a man, or does so at a developmentally significant time, the male may develop a chronically hostile interpersonal style. Thus, the male will be easily angered and resort to coercion and force to assert his dominance whenever he perceives that a woman is threatening his reproductive success.

Dean & Malamuth [16] introduced a third component to the confluence model- the influence of a high-dominance, low-nurturance approach to interpersonal relationships. This personality style is distinguished by self-interested motives and goals, a lack of compassion or insensitivity and little concern for potential harm to others [14]. Malamuth and colleagues suggested that the level of dominance or nurturance traits develops as a result of early childhood socialization and the incorporation of familial and cultural messages. Malamuth, et al. [14] also believed the development of a dominant personality style was due in part to evolutionary processes. Using quantitative methodology, Yucel established factors that influence sexual aggression and their contribution to the overall confluence model of sexual aggression (Figure 1) [17].

A theory involves inductive reasoning that brings across a certain phenomenon [18-22] which is the rationale for its usage in this research. This study uses a confluence model to explore issues explaining sexual assaults against young adult Jamaicans. It examines whether the perpetrators used aggressive behavior such as threatening, physically harming the victims and using dominance to intimidate and inform the victim that nobody should be told about the assault.

Literature Review

The Sexual Offense Act 2009 defines rape as the use of physical force or to penetrate an individual without consent, this takes into consideration marital rape where a husband can rape his or her spouse in specified circumstances [1,2].

Rape is a form of sexual assault, but not all sexual assault is rape. The term rape is often used as a legal definition to specifically include sexual penetration without consent. For its Uniform Crime Reports, the FBI defines rape as "penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim."

RAINN's definition provides some context for sexual assault of people. Hence, sexual violence in the home is the same in Jamaica as is the case across the world. The reality is women are more at risk of sexual violence in the homes as men. Women are nearly thirty (30) times more likely than men to be sexually assaulted by family members and family friends [23].

Rape can be a one-time occurrence, or it can be ongoing and may involve the use of alcohol and other drugs hence it makes the victim more vulnerable. In some instances, weapons were brandished to force the victim into performing sexual acts. Many perpetrators of Confluence Model of Sexual Aggression (CSA) were male relatives or someone in their neighborhood. Perpetrators of some sexual assaults were not previously known to the victim and the attack occurred at random. Some victims were on their way from various places when they were assaulted. Children require protection from sexual violence in the home. The Jamaica Injury Surveillance system has shown that eighty-six percent (86%) of sexual assault cases reported in 2002 and 2003 were committed by a relative, a friend, and or an acquaintance. One of the most enduring misperceptions commonly expressed, is that sexual violence is at the fault of the victim, due to his/her behaviour [24].

Sexual abuse impacts both genders and it is seen to be common in Jamaica. In many instances, the abuse is so deeply entrenched into the Jamaican culture that it is generally condoned as men being men. In the meantime, many victims of rape suffer in silence, refusing to get help from the relevant agencies because of the societal culture, and so they tend to mask the real situation as it relates to the crime of rape. Sexual abuse impacts both genders it is seen to be common in Jamaica.

A study by Bourne, et al. [25] revealed that for at least four decades (1970-2013), "...on average, 778 ± 465 people (95% CI: 626-931) were murdered in Jamaica compared to 1,062 ± 333 (95% CI: 952-1,171) who were raped or carnally abused" (p. 588). They referred to sexual violence as a new pandemic and this was before COVID-19. Furthermore, Bourne, et al. [26] found that there were 590 ± 109 cases of rape and/or carnal abuses in Jamaica for decades of the 1970s (1970-1979) followed by 901 ± 127 cases in the 1980s (1980-1989) and this increased to 1,295 ± 268 in the 1990s (1990-1999) and marginally decrease to 1,232 ± 116 in 2000s (2000-2009). The matter of rape and/or carnal abuse as well as intentional homicide is at a pandemic stage with little policy emphasis to address this public health crisis.

Another study by Bourne, et al. [27] found that the average rape and/carnal abuse rate in Jamaica for a 44-year period (1970-2013) was 43.9 ± 11.0 per 100,000 population compared to 23.5 ± 6.2 per 100,000 population for New York. Comparatively, the average homicide rate for the period (1970-2013) was 8.6 ± 3.6 per 100,000 population for New York and 31.0 ± 16.2 per 100,000 population of Jamaica. The reality is, one is more likely to be raped in Jamaica than New York as well as in Jamaica. Rape is expressed through sex but is not primarily about sex, and the number of cases is at least 480 per year since 2014-2019 [28,29]. The violent act is for most victims an unforgettable crisis that can lead to depression, insomnia, sexual dysfunction, difficulties with relationships, fears, phobias, nightmares, and several other mental conditions. Some victims will never recover emotionally from rape; post-traumatic stress disorder, (PTSD) is a common complication associated with sexual assault. More than fifty percent (50%) of rape victims have some difficulty in re-establishing relationships with spouses, partners, or, if unattached, in re-entering the "dating scenes."

Based on research conducted there was little recourse for justice as the current definition of rape in Jamaica does not consider forcible anal penetration as rape but as "buggery". The culture legal framework only protects females who are survivors of forcible sexual violence under the law criminalizing carnal abuse. This narrow definition creates barriers for male survivors of sexual violence. Some males were preyed on because they were perceived to be sexually available and because of their assumed homosexuality. These individuals were less likely to report the abuse and assault. Some individuals were assaulted by persons with power and privilege, this was done by perpetrators from respectable organizations such as police officers and persons who hold positions within churches.

These activities started from unwanted and inappropriate touching. This was used to test the boundaries of the targeted individuals, which escalated to the exposure of genitalia and ended in direct nonconsensual sexual acts. These tactics are not new but are commonly seen in other instances in our society, of sexual assault among adults. Other settings depict that gay and bisexual men in Jamaica often fail to report crimes committed against them to the police, fearing that the police would be unresponsive to their claims because of their sexual orientation [24].

Methods and Materials

This research employed a correlational research design and collected data using a web-based standardized survey method. The survey was distributed via various social media platforms such as WhatsApp, email (google forms), and face-to-face interactions. The data were from young Jamaican adults across the 14 parishes by way of purposive sampling method. Data collectors were trained in the areas of ethics and data collection, and they were assigned to all the parishes across the island. They collected data from their parishes via a web-based instrument. The instrument consists of twenty-five (25) closed-item questions. These questions aim to obtain demographic data, assessing the gender of the assaulted, where the incident took place, if it was reported, sexual activity, and the frequency of the same. The survey was conducted from June 1 to August 1, 2021. Using purposive sample, some five hundred and six (506) young Jamaican adults ages 18 to 30 participated in this study and sample was determined based on the population for 2018 [10]. The data were analyze using descriptive conjectural statistics, and cross tabulation via the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows Version 25.0. A p-value of at most 5%, was used to determine the level of significance.

Results

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of Sampled Respondents shows that 26.9% of the respondents were males and the remaining 72.9% were female. The table also shows the age of respondents starting with under 18-years with 4% of the respondents, 18-22 with 46%, 22-24 25.5%, 24-26 4.5%, 26-28 9.3%, 28-30 with 14% and the remaining 2% to 44-years.

Of the sampled respondents (n = 506) most of them were females (72.9%) and between the age range of 18-22 (46.0).

Table 2 represents factors relating to sexual assault. Firstly, it shows that 36.4% of the respondents were sexually assaulted and the remaining 63.6% were not. Secondly it shows where the incident took place 13.8% of the respondents were assaulted at home, 1.8% in bushes, 1.2% in a taxi, 0.8% at church, 4.2% in a vehicle other than a taxi, 1.6% at work, 1% at a friend's house, 4.3% at school, 0.2% at the beach, 0.4% at a villa, and the remaining 0.4% while coming home. Forty-six per cent of the respondents indicated that they have been threatened, 31.6% have been physically assaulted, and 52% stated that they informed someone of the sexual encounter.

In order to assess particular research questions, this section of the findings will present some cross-tabulations.

H0: There is no statistical relationship between the sexually assaulted young Jamaican adults and gender

H1: There is a statistical relationship between the sexually assaulted young Jamaican adults and gender

Table 3 represents a Cross-tabulation between the sexually assaulted young Jamaican adults and gender. The findings reveal that there is a statistical relationship between the two aforementioned variables (χ2 critical is = 9.348 < χ2 obtained = 36.275, p = 0.000) hence, we reject the null hypothesis, hence there is a statistical relationship between the two variables, females are more likely to be sexually assaulted than males.

The table also shows that individuals who identify with both genders are most likely to be sexually assaulted followed by those who identified as non-binary followed by those who selected female to be there and finally the least likely to were those who identified as males.

Table 3 shows that 56.4% of the female respondents were not sexually assaulted while the remaining 43.6% were sexually assaulted. The table also shows that 63.6% of the male respondents were not sexually assaulted while the remaining 36.4% were sexually assaulted. In addition, 87.0% (n = 160) of sexually assaulted respondents were females compared to 11.4% being males (n = 21).

Table 4 presents a cross-tabulation of sexually assaulted young people and gender. Of the sampled respondents (n = 506), 36.4% have been sexually assaulted for the studied period. Eighty-seven per cent (n =160) of the sexually assaulted young Jamaicans were females compared to 64.3% of those who were not sexually assaulted. Furthermore, 11.4% (n = 21) of the sexually assaulted young Jamaicans were males compared to 35.7% (n = 115) who were not sexually assaulted (χ2 (3) = 39.275; P < 0.0001). In addition, young female Jamaicans were 7.6 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than young male Jamaicans.

A cross-tabulation between being sexually assaulted and age cohort is presented in Table 5. Forty and three tenths per cent of those ages 22-24 years-old were sexually assaulted compared to 36.9% of those 18-22 years-old, 100.0% of those less than 18 years, 34.8% of those ages 24-26 years-old, 29.6% of those 28-30 years, and 31.9% of those ages 26-28 years, with there being no statistical association between previously mentioned variables (χ2(6) = 6.809, P = 0.339).

Of the 184 respondents who indicated being sexually assaulted during COVID-19, 84.8% (n = 156) provided a description of the perpetrator (Table 6). Of the 156 sexually assaulted respondents, the majority of them were assaulted by friend/family friend (38.5%, n = 60) followed by a family member (excluding father/stepfather, 25.6%, n = 40), a stranger (14.7%, n = 23), father/stepfather and taxi operators (4.5%, respectively).

Seventy-six per cent of those who indicated reporting the abuse to someone were sexually assaulted compared to 95% of those who did not report the matter to anyone (χ2(1) = 15.109, P < 0.0001; Table 7).

Of the 184 young Jamaicans who have been sexually assaulted during COVID-19, 96.2% (n = 177) have provided answers to the types of act encountered. Penile penetration was the most frequently occurring act of sexual assault against young Jamaicans (49.2%, n = 87) followed by fondling the genital/genitalia (33.9%, n = 60). One in every two sexually assaulted young female Jamaican had experienced penile penetration during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to nine in every 20 young male Jamaicans (χ2(1) = 105.223, P < 0.0001).

Discussion

Sexual assault is one of the most traumatic types of criminal victimization, and Faupel & Przybylski [29] opined that sexual abuse is a learned behaviour. While persons who fall victims to the assault may find it difficult to engage in the discussion involving the topic. Many victims of sexual assault are intensely traumatized not only by the humiliation of their physical violation but by the fear of being severely injured or killed, and this is more so for the sodomized young males in Jamaica. The current study found that one in every two sexually assaulted young female Jamaican had experienced forced penile penetration during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to nine in every 20 young male Jamaicans (χ2(1) = 105.223, P < 0.0001). In addition, 87% of the sexually assaulted young Jamaicans are females and 11.2% being males.

Sexual assault is notably under-reported and under-prosecuted because of what many consider to be sexual assault others recognize as "normal" sexual behavior between adults in our society [23]. Another notable rationale for the under-reporting of sexual assaults is because the perpetrators are known to the victims inclusive of biological family members. The current reality is, 85.3% of the sexually assaulted young people in this survey indicated that the encounter was carried out by someone they know (father/stepfather, other family members, taxi operators, co-workers, partners), and this may account for the challenge in reporting the incident. The current findings on cases of sexual assault among young Jamaicans during COVID-19 is in keeping with reports from the Jamaica Injury Surveillance system dating to 2002 and 2003 (86%) [24].

Sexual assault is associated with numerous negative complications, whereas victims can face immediate psychological, emotional, and physical consequences as well as chronic effects that can impact their adjustment throughout their daily lives. This research is geared towards determining whether females are more likely to be assaulted, sexual assaults occur in an environment where victims are presumed to feel safe, or sexual assaults are likely to be reported.

Based on the data obtained from the survey it was evident that most of the respondents were female, which accounted for seventy-two-point nine percent (72.5 %) whereas twenty-six-point-nine percent (26.9%) were males. Persons who viewed themselves not as male or female but as both sexes showed a non-binary figure which accounted for zero-point-six percent (0.6%). Table one also reported on the age of the respondents, which ranges from 18-30 years-old. Persons under the age of 18-years-old accounted for 0.4% or two persons which was the least number of respondents by age groups. Respondents between the age of 18-22 years-old reckoned for forty-six percent (46%) or 233 persons, walking away with the highest number of respondents by age group. Persons of ages 22-24 years-old accounted for twenty-five-point-five percent (25.5%) or 129 respondents. Ages 24-26 years-old accounted for four-point five (4.5%) or 23 persons, ages 26-28 years-old accounted for nine-point three percent (9.3%) or 47 persons whilst persons between the age 28-30 years-old accounted for fourteen percent (14%) or 71 persons. However, the survey further shows that the majority of the assaults happened at home, and the home should be a safe place instead people are mostly assaulted there.

Malamuth's Confluence Model indicates that men are more likely to be the perpetrators of sexual assault, because men are likely to engage in promiscuous-impersonal sex and use hostile masculinity and aggression to coerce sexual acts. Results from this research have shown in Table 1 that 26.9% of the respondents were males and the remaining 72.9% were female. Table 3 shows that 56.4% of the female respondents were not sexually assaulted while the remaining 43.6% were sexually assaulted. The table also shows that 63.6% of the male respondents were not sexually assaulted while the remaining 36.4% were sexually assaulted. Again, females are more likely to be assaulted than males. Males are more likely to commit sexual assault on females. Females are inferior to men in terms of strength. Men assert their dominance through coercion and aggression towards females leading to assault. Home, Church, School are examples of environments where people are presumed to be safe. Table 2 shows that the majority of the respondents were assaulted at home 13.8%, followed by at school 4.3%, then 4.2% in a taxi. The research proves that these incidents take place in an environment where individuals feel safe. Table 2 shows that 21.3% told someone of the incident and another 20% did not tell anyone. It also shows that 13.0% were physically harmed and another 28.35 were not. Additionally, 17.6% of the respondents were threatened and 20.9% were not.

The majority of the respondents told someone of their incident of sexual abuse. Majority of the respondents were not threatened, and the majority of the respondents were not physically harmed. Physical violence is also a feature of sexual assaults, and the victims exposed to more than one traumatic experience following the event. A study by Arscott-Mills, et al. [30] revealed that the highest reported cases of injuries recorded at the Accident and Emergency units in hospitals in Jamaica were physical injuries (51%), and that some of cases would have included sexual assaults. Based on the findings of this research, the assumption is made that the perpetrators of these sexual acts commit these acts as a means of sexual pleasure or reproduction, furthermore majority of the respondents were not threatened yet by a small margin of 1.3% separates who told someone of their incident. In summary, females are more likely to be assaulted. Sexual assaults occur in an environment where victims are presumed to feel safe, and sexual assaults are likely to be reported.

Conclusion

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, this analysis of data, research, and experience show that sexual assault remains a serious and pervasive problem here in Jamaica. The research has also shown that it has gotten worse, due to the COVID-19 pandemic which caused persons to be home for a longer period. To conclude, the survey has found that female assault is more prominent, with the majority of incidents occurring in the home, in an environment where victims are presumed to feel safe.

Recommendations

It is the recommendation of the researchers who conducted this study for Policy makers to implement measures to protect women from sexual assaults and that they address a pending public health crisis that may include sexually transmitted infections, post-traumatic stress disorder, and unwanted pregnancy.

The current findings did not examine the obvious long-term consequences of sexual assault. According to Dube, et al. "Compared with those who did not report CSA, men and women exposed to CSA were at a 40% increased risk of marrying an alcoholic, and a 40% to 50% increased risk of reporting current problems with their marriage (p < 0.05)" [31]. Hence, this study is forwarding that the long-term effects of sexual assault should be brought into discourse.

References

- (2011) Sexual offences act 2009. Ministry of Justice (MoJ), Kingston: Jamaica.

- (2021) Sexual assault. RAINN.

- (2021) Sexual assault. US. Department of Justice.

- Leserman J (2005) Sexual abuse history: Prevalence, health effects, mediators, and psychological treatment. Psychosom Med 67: 906-915.

- Types of sexual violence. RAINN.

- (2021) Sexual and reproductive health: Sexual violence. World Health Organization.

- Smith D, McLean Cooke W, Morrison S (2019) A discussion on sexual violence against girls and women in Jamaica. Journal of Sexual Aggression 26: 1-12.

- Dunkley Willis A (2021) Sexual savagery. Kingston: Jamaica Observer.

- Bourne PA, Hudson Davis A, Pryce S, et al. (2015a) Homicide, rape and carnal abuse in Jamaica, 1970-2013: The New Health Pandemics. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience 17: 588-597.

- (2019) Population statistics: (Total) End of year population by age. Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN).

- Elntib S, McPherson P, Ioannou M, et al. (2018) When sex is more than just sex: Evaluating police perspectives regarding the challenges in interviewing victims of sexual offences in Jamaica. Policing and Society 30: 255-275.

- Huntington C, Pearlman DN, Orchowski L (2020) The confluence model of sexual aggression: An application with adolescent males. J Interpers Violence 37: 623-643.

- Malamuth NM, Hald G (2017) The confluence mediational model of sexual aggression. In: D. P. Boer Ed the Wiley Handbook on the Theories, Assessment, and Treatment of Sexual Offending.

- Malamuth NM, Heavey CL, Linz D (1996) Confluence model of sexual aggression: Combining hostile masculinity and impersonal sex. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 23: 13-37.

- Malamuth NM, Linz DH, Barnes G, et al. (1995) Using the confluence model of sexual aggression to predict men's conflict with women: A 10-year follow-up study. J Pers Soc Psychol 69: 353-369.

- Dean KE, Malamuth NM (1997) Characteristics of men who aggress sexually and of men who imagine aggressing: Risk and moderating variables. J Pers and Soc Psychol 72: 449-455.

- Yucel E (2019) Reassessing the confluence model of men's risk of sexual aggression.

- Babbie E (2010) The practise of social research. (12th edn), Ohio: Wadsworth.

- Creswell WJ (2013) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach 4th edition, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. SAGE Publication Inc.

- Crotty M (2005) The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. London: SAGE.

- Theory. Merriam Webster.

- (2006) Sexual violence against women and girls in Jamaica: "just a little sex. Amnesty International.

- Neuman WL (2014) Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. (7thedn), New York, Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

- Harris OO, Dunn LL (2018) "I kept it to myself": Young Jamaican men who have sex with men's experiences with childhood sexual abuse and sexual assault. Arch Sex Behav 48: 1227-1238.

- Bourne PA, Hudson Davis A, Sharpe Pryce C, et al. (2015b) Rape, carnal abuse and marriage in Jamaica, 1970-2013: Is there non-consensual sex in marriage? World J Pharm Pharm Sci 4: 199-230.

- Bourne PA, Hudson Davis A, Sharpe Pryce C, et al. (2015c) Homicide, sexual homicide and rape: A comparative analysis of Jamaica and New York, 1970-2013. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 4: 231-260.

- (2017) Justice and crime. Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN).

- Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC) (2020) Jamaica 2020 crime & safety report.

- Faupel S, Przybylski R (2015) Chapter 2: Etiology of adult sexual offending.

- Arscott-Mills S, Gordon G, McDonald A, et al. (2002) A profile of injuries in Jamaica. Inj Control Saf Promot 9: 227-234.

- Dube S, Anda R, Whitfield C, et al. (2005) Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. Am J Prev Med 28: 430-438.

Corresponding Author

Paul Andrew Bourne, Acting Director of Institutional Research, Northern Caribbean University, Mandeville, Manchester, Jamaica, WI.

Copyright

© 2022 Bourne PA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.