Ethnomedicine Museums On-Call: How Cultural Heritage is Addressing Health Challenges

Abstract

The internationalisation of diseases and cultural pluralism are increasingly characterising our societies. This contribution highlights the role of cultural values in the definition of health and the practice of caring. Today, an approach to health and wellbeing mediated by anthropology and the medical humanities more generally and supported by the expressions of material and immaterial culture is necessary to review our way of conceiving health and its promotion.

In the syllabus of the Health Anthropology teaching provided in Nursing and Midwifery degree courses of the School of Medicine of the University of Genoa, an in-depth study on the care systems in different cultures was included through an experiential activity carried out at the Museum of Ethnomedicine of the University of Genoa (Italy). The Museum, unicum in the world, collects traditional medicines from the five continents. In order to foster critical thinking in health education, students were asked to explore the care systems of other cultures through artefacts, images, and videos in the Museum, in the form of cooperative and collaborative learning.

This research aims at evaluating the interest in acquiring anthropological skills in the caring relationship by healthcare students and the didactic effectiveness of an experiential module involving cultural heritage integrated into the traditional teaching course of Health Anthropology.

In the last three academic years before the COVID-19 pandemic, 1140 first-year students in Nursing, Paediatric Nursing and Midwifery were involved in this engaging and interactive teaching approach. The pilot study showed a very high level of student satisfaction and underlined the crucial role of heritage mediated by an intercultural approach.

A museum experience integrated into a humanisation of care teaching can be an essential part of the educational toolkit for health professions degree courses. It encourages the development of crucial skills for professional life, such as reflection or critical thinking skills; it offers a more open and inclusive view of other cultures and practices of care; it stimulates continuous professional development and a constant search for excellence.

Keywords

Anthropology of health, Science museum, Traditional medicine, Medical students, Visual thinking strategies

Introduction

There are many uses of art in the field of health. Tangible and intangible heritage plays a crucial role in the physical and mental wellbeing of individuals and communities in terms of 'perspective', memory, beauty, and 'places of refuge'.

Many good practices consider the impact of cultural heritage on people's wellbeing and on the reduction of specific health conditions [1,2]: From art therapy to the "re-construction" of health care places to increase patients' wellbeing following the holistic orientation indicated by the World Health Organisation.

The concept of humanisation in health care has developed around this approach and is based on the evolutionary process that has seen changes in the understanding of 'health' and the means used to ensure it. The transition from the biomedical approach to the bio-psycho-social approach has introduced a multidimensional view of health, shifting the focus from the diseased organ to the individuals, as a whole. It has definitively established the principle of the 'centrality of the patient'.

In this renewed cultural context, the patient is understood not only as a carrier of pathology but also as a person with physical, functional, psycho-emotional, relational needs, and an inalienable world of values.

At the international level, the concept of humanisation, referring to patients and their caregivers, is expressed by the term 'patient-centred care' according to which, as the International Alliance of Patients' Organization (IAPO) states, the "system of care should be designed around the patient with respect for the person's preferences, values and/or needs" [3].

An approach characterised by dimensions such as respect for the values, preferences and needs expressed by the patient finds its primary references in the Medical Humanities, born in the United States in the 1970s, which represented a long process of rediscovery of the relational and narrative dimensions of medicine, favouring, in the doctor-patient relationship, aspects specifically related to the human and personal dimension. The Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) model has spread in contemporary medicine, with enormous and unquestionable merits, leading to the incredible development of the therapeutic potential of contemporary medicine. However, every development is not without risks. The practice of EBM, detached from the anthropological vision of health, has gradually led to see, as the object of its practice, no longer the patient, but the disease, no longer the sick person, but the body or the sick body part, in a progressive process of alienation.

This situation and important consequences in the relationship with the patient, which we will see later, leads to a progressive impoverishment of the diagnostic process, reduced to instrumental analysis.

The Medical Humanities movement has reacted to this situation with various sensitivities and approaches. It represents an important development of awareness within the medical environment as a reaction to medical activity that is excessively oriented towards a fragmented and technological practice. The Medical Humanities make it possible to develop an in-depth reflection on the significant recurring themes in the socio-health field, such as the relationship with the patient, the meaning of illness, death and dying, and the relationship between medicine and culture. These experiences, which must be known and explained in health contexts scientifically, can hardly be understood in their meaning through such activities. The Medical and Health Anthropology, and the Medical Humanities in general, can represent a way of teaching and getting to know the experience of illness in all its complexity, developing observational and interpretative skills and constructing the meaning of illness.

Thus, the role of Medical Humanities in training health personnel would be to build soft skills in correlation with the hard skills constituted by the biomedical and surgical disciplines.

A crucial element is to recover a correct relationship in the clinic. The explosion of evidence-based medicine and, more specifically of instrumental diagnostics, with the enormous potential it has brought with it, has increasingly eclipsed the traditional anamnesis. Conversely, as significant studies have shown [4], contextual factors linked to the patient also emerge in the clinical interview: the patient is not a monad, but lives embedded in a system (social and family) whose individual parts are mutually interconnected. Therefore, the disease impacts not only the biological level but also the entire family and social system. An intervention or a healing plan must necessarily consider the context, values, practices, and traditions of the culture it belongs to.

The training of future doctors, nurses, and other health professions, historically embedded in scientific curricula that offer little or no scope for interdisciplinary medical-humanistic reflection, must necessarily pay attention to the different cultures that coexist in the same area.

Thanks to the introduction of the Medical Humanities into university curricula, particularly the anthropological perspective, new paths for the training and updating of professionals have been opened.

In this context, art can also play an essential role in medical education. Several studies have suggested that art can be used to address the different needs of healthcare staff training [5]: Reflection, critical thinking skills, observational skills [6,], better communication, empathy, as well as improved resilience to limit the risk of stress and burnout [1,7,8].

On the other hand, there is little research on the use of cultural heritage as a tool for social inclusion in the training of future health professionals, who must necessarily be open to the cultures of peoples to take care of everyone under the beliefs and practices of the culture they belong to.

However, an even more intriguing aspect stimulated by the Anthropology of health and the cultural heritage linked to the medicines of peoples (ethnomedicine, ethnopharmacology, ethnobotany, etc.) offers a more specific look. It is a vehicle for criticising the dominant Western paradigms in medicine. Such a look intends to indicate a path to stimulate us to know how other cultures have dealt with problems related to health/disease, bringing us to our reality with greater acquired awareness, able not only to know other procedures but also to look at our own with critical awareness.

Spindler & Spindler [9] argue that cultural education and cultural transmission are never separated, except by convention, in an overview of anthropology and education. Framing education as cultural transmission highlights the need to teach students the values and knowledge essential to operating effectively in a particular culture. The authors [9] use the term "cultural compression" to refer to a specific form of cultural transmission that occurs at any point in life, when an individual may encounter cultural restrictions that affect the role he or she plays at that moment in his or her group and society, and that affects him or her with the most incredible intensity, leading to a change in social identity. This concept is particularly significant for the health professions, where training experiences are traditional learning methods and internships are intense and rigorous.

Certain features of medical education, such as a lack of attention to other cultures and their different systems of care, favour 'cultural compression'.

Within this framework, do museums of traditional peoples' medicines have something to offer to health education? Do they play a role in improving the holistic education of medical students?

This is the background of this study, which aims to combine an anthropological perspective with an experiential activity for health professions students in a unique museum, the Museo di Etnomedicina A. Scarpa of the University of Genoa, Italy.

Anthropological perspectives between the life sciences and the humanities

The movement of peoples increasingly brings about the need for a new cultural awareness of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, and other health professionals.

We have become familiarised with a social context that is not very oriented towards the culture of otherness and treating all patients in the same way without considering their different cultural backgrounds, which is a clear sign of professional ethnocentrism.

The need for an anthropological approach to the 'health system' goes to the very heart of politics and civil coexistence, especially where the phenomenon of immigration and the new social and cultural stratifications involve forms of exacerbation of poverty and marginality.

Health professionals must be encouraged to reflect on these elements and acquire the ability and willingness to listen to and observe their diversity and others'. Anthropology plays an important role here.

Rivers (1927) [10] was the first to conceptualise medicine as a cultural system and medical systems as integrated strategies of socio-cultural adaptation.

A medical system comprises all the beliefs, actions, scientific knowledge, and techniques that promote the health of a human group. The anthropologist has the task of assessing differences in human behaviour in care as an expression of the division between different human groups produced by culture. In the list of adaptive responses to life's challenges, there are theories of health and illness that cannot be understood without knowing the culture and social structure of the groups that transmit them [11].

Medical anthropological research has shown that, in contrast to the Western world, cultural definitions of illness in other populations are characterised by the dependence of health imbalances on other domains of social reality such as family organisation, political relations between groups and environmental interactions [12,13].

The ethnographic description of peoples' beliefs and behaviour has been and still is often tainted by an ethnocentric bias that tends to devalue what differs from the observer's culture.

According to Jaspers [14], the figure of the health professional is characterised by 'scientific knowledge and technical skill on the one hand, and a humanitarian ethos on the other'. The two traits refer to two very different scenarios, which are not easy to see composed and unified in a single personality.

Leininger (1978) [15], the first nurse to ask what role culture should play in the expectations of nurses and nursing care, stated that: 'For human beings to live and survive in a healthy, tolerant, and meaningful world, it is necessary for nurses and other health professionals to learn the beliefs, values, and lifestyles of culturally related peoples in order to provide valid and culturally congruent health care.'

As pointed out by Alici, et al. [16], universities need to prepare future health professionals who also have knowledge of anthropology, sociology, psychology, bioethics, and epistemology.

According to Antonio Guerci [17], humans are subject to a historical variable; human beings are not the result of already available data (genetic, ecological, etc.). However, in constant evolution, they result from a long process of 'humanisation' which transforms and shapes them both culturally and physiologically. Each person who falls ill is part of a worldview that must be considered in interpreting symptoms, illness, and relationship with the sick body.

Moreover, while illness is an individual issue, health is a collective issue, and is now a social issue at the heart of the anthropological question. Having become a reference value, health is defined as a socially and politically elaborated construction whose limits are constantly being re-discussed, especially in the unprecedented, globalised context in human history [18].

Anthropology applied to health and medicine is the product of a multiplicity of voices and experiences; it aims to combine and make medicine 'the realm of rationality and the natural sciences' interact with the fundamentally historicist vision of anthropology, according to which 'all knowledge is cultural and relative to an era and a historical perspective': This can lead to the development of new languages and new research methods, so as both to advance empirical research and to open up the field to a more humane treatment practice [19].

Looking at biomedicine from an anthropological perspective, exploring the intertwining of material bodies with history, environment, culture and politics, Lock and Nguyen criticised the biological sciences' assumption of a universal human body that can be uniformly standardised [20].

In fact, despite the cruciality of an approach that considers the body not so much as a 'natural' object, but as a historical product, i.e. a cultural construction that varies according to the different social contexts, not all the programmes of degree courses in the health area in Italy have considered it essential to introduce an anthropological look at the world of care [21] or have included the teaching by integrating it with the disciplines characterising the course of study.

In contrast, the degree courses in Nursing, Paediatric Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Genoa (Italy) have shown great attention to this issue. For more than ten years, they have included an integrated course entitled 'Nursing in models and relationships of care' in their curriculum, focusing on the anthropological view of illness and health.

After the first years of implementation in a traditional way with lectures and case discussions, the teaching was integrated with a visual, emotional, and reflective experiential module through in-person visits to a unique museum, the Museum of Ethnomedicine Antonio Scarpa, of the University of Genoa, Italy.

Human care: A journey through images

Genoa is increasingly becoming a multicultural and multi-ethnic city. In this context, not devoid of conflicts and potential riches, the study of traditional medicines represents a privileged bridge to bring together immigrant communities and national and local institutions, cultures, and individuals.

Antonio Scarpa (1903-2000), medical doctor and periodeuta, travelled the five continents for almost sixty years, collecting objects, remedies, instruments, texts, etc., concerning the traditional medicines encountered, observing that the different therapies were based on a cosmological and ecological principle aimed at restoring social, mental, and physical order.

The Scarpa collection constitutes a unique collection of objects from over one hundred human groups related to the different medical traditions of the world. The approach to Traditional Medicines includes a highly topical reading of health, anthropological, social, and ecological problems related to health, wellbeing, and the environment.

To cure himself, man has always drawn remedies from his habitat, adopting different therapeutic strategies depending on the climatic, pedological, phytogeographical and faunal characteristics, and the cultural and socio-structural typologies.

Every human population, in every age, through its culture, constructs a particular representation of the world, resulting in specific constructions of the body and thus of health and illness.

Starting from a peculiar perception of the body, anatomy, physiology, biology, the position of the human being in the animal world, the notion of normal and pathological, each culture elaborates a constituted knowledge, transmits it, declines it in the everyday world and on institutional occasions.

Through the exhibition of a selection of artefacts, images, iconographic material, and films from the Scarpa collection, the Museum can provide students in the health area with elements of understanding for a plural approach to healing and caring. The study of the traditional medicines of peoples follows an itinerary in time and space through the preventive, hygienic and curative procedures of the populations that have inhabited and still inhabit our planet. Starting from this plurality, the aim is to stimulate future health professionals to enhance and spread the culture of "taking care", thus encouraging the transition from a vision of illness as an individual event to one that interprets it as a collective-social fact.

The Museum presents itself as a facilitator to improve the understanding of populations' culture and cultural productions, including their knowledge of traditions, practices, rituals, and other forms of expression related to health and healing. This contributes to the development of social norms that hold society together regarding conflict prevention and the reduction of prejudice and discrimination [22].

The collection embraces a dynamic and dialogical notion of 'cultural heritage', understood as a resource that can be authentically shared by all and continuously put back into play, and not just preserved and transmitted.

It promotes the respect, promotion, and preservation of cultural diversity, recognising that 'the past is a foreign land', even more difficult to decipher for those from 'elsewhere'.

Intercultural education is perceived as the only education capable of helping all citizens, young or old, build their future projects and dialogue in a plural society.

To promote the free participation of citizens in the cultural life of their society and to enable them to express their cultural identity, the Museum's mission supports the development of relational skills and dialogical identities and not only of disciplinary knowledge.

In line with this, the Museum has been a place of study and in-depth education of traditional healing practices open to medical students for years.

Methodology

Design overview

The teaching of Health Anthropology for the degree courses of the Health Professions of the Medical School of Genoa has been developed for years around an in-depth study of medicine in different cultures and is enriched by a visit to the Museum of Ethnomedicine A. Scarpa of the University of Genoa, Italy.

The course's main objectives are to enable students to address issues related to health, environment (biotic and abiotic) and disease from an 'anthropological perspective'; to raise awareness of the close relationship between human beings and their natural and social environment; to explore traditional healing practices.

The course is divided into three didactic modules ("Anthropology and Human Variability", "Anthropology of Health and Interaction between Care Systems") and an experiential module ("Care in Other Places" through the collection of the Museum of Ethnomedicine).

The teaching activity is carried out in blended mode, online for the theoretical part of the first two modules and in presence in small groups for the experiential part at the Ethnomedicine Museum for a total of one university credit. The visit implies dividing students into small groups and an approximate time commitment at the Museum of two hours. A teaching method is applied that enhances critical thinking skills through discussions of visual images facilitated by the teacher. This is achieved thanks to the more than 1500 objects related to traditional healing practices collected on the five continents by Antonio Scarpa.

Before starting the course, a survey was conducted to determine the students' interest in visiting the Museum of Ethnomedicine, sharpen their intercultural competence in the approach to care, and refine their reflective skills. In the three years observed, the survey results confirmed the interest in visiting the Museum, so a guided tour was organised for groups of students. The experiential activity is structured as follows.

During the visit, the pupils are asked to choose an artefact, observe it carefully, note down comments and answers, explore the Museum to find further stimuli, and then return to the chosen work and note down any new impressions. The in-depth study of the artefact was planned to be done alone or in groups, with the help of the documentation in the Museum or the teachers, depending on the preferences of each student.

Halfway through the visit, students are invited to discuss the selected artefact and their initial observations to compare and find new stimuli before returning to the selected artefact.

Each student is asked to complete a one-page reflection task on the museum experience, to be handed in within two weeks of the visit and in any case before the final assessment exam. Two weeks was considered adequate to process the experience and stimulate links with their own academic learning, skills development, and life experience. Finally, students were asked to respond to the following three statements:

- Describe the artefact you chose during the visit in as much detail as possible.

- Explain how the work makes you feel.

- Compare and contrast your initial impressions with your new impressions.

The final examination considers the answers to a multiple-choice questionnaire on the topics covered in the first two modules, the Museum's experiential part, and the related reflection on the artefact selected during the visit.

At the end of the course, the students were given a questionnaire to investigate the usefulness of an anthropological approach to medical education. During the small group meetings, some ideas prepared by the teachers were discussed to investigate the effectiveness of the third experiential module.

Objective

This study aims to evaluate the interest in acquiring anthropological skills in care relationships and the effectiveness of an experiential module integrated into the teaching of Anthropology of Health at the Museum of Ethnomedicine A. Scarpa. Scarpa.

Target

The target population consisted of 1140 first-year students enrolled in nursing, paediatric nursing, and midwifery courses in the last three academic years before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tools

The perceived usefulness of teaching health anthropology to health professionals was determined using a questionnaire with four items anchored to a Likert scale (0 = totally disagree and 10 = totally agree).

The second objective, to assess the interest in the experiential module, was assessed through the reflections made at the end of the museum visit by the small groups of students on the crucial role of an intercultural approach in heritage mediated care. The reflections were carried out based on suggestions previously elaborated and proposed to all groups, leaving the debate open and stimulating the interaction of all students. These activities were carried out before the examination to avoid any bias related to the formative assessment.

Results

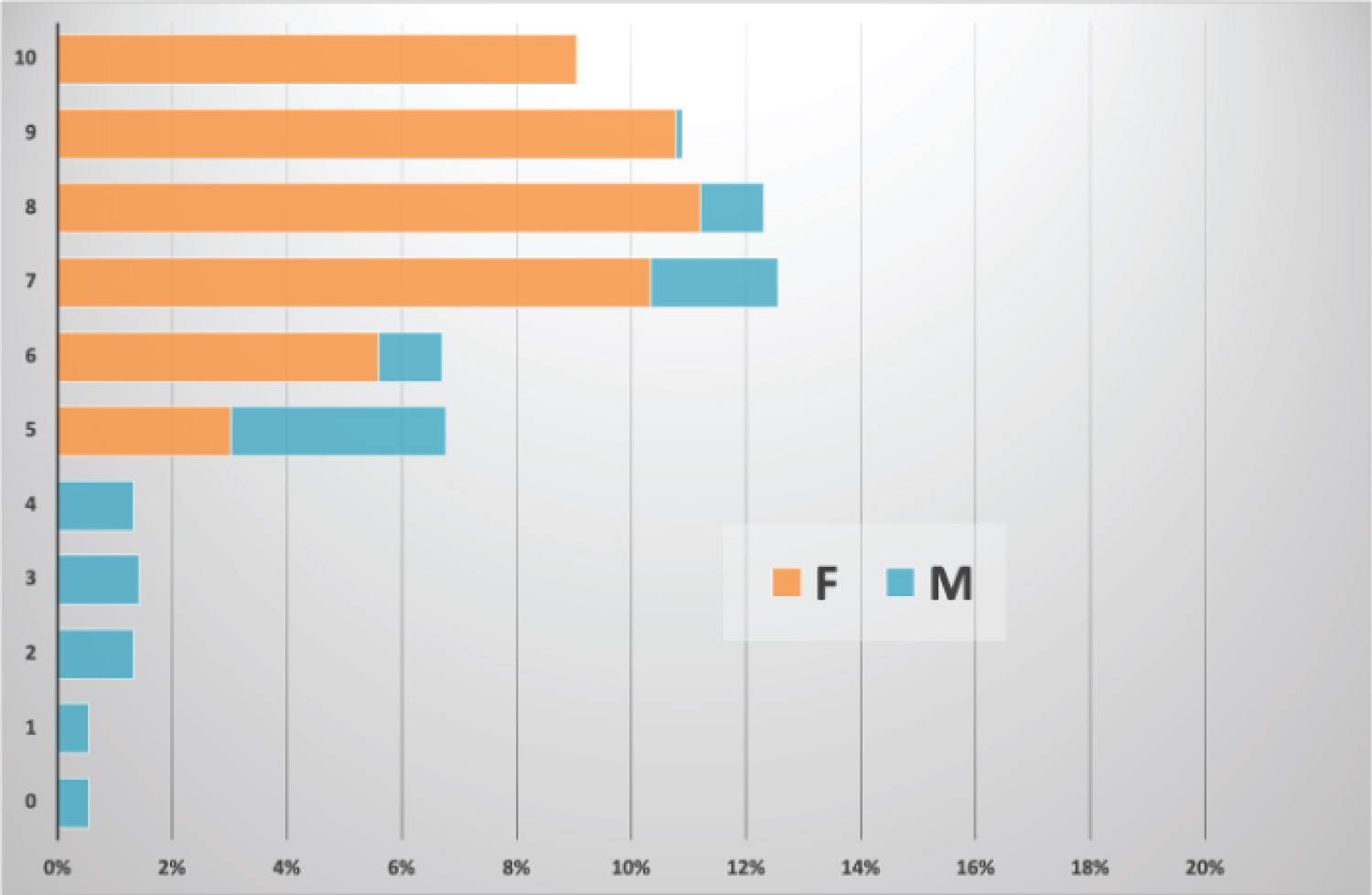

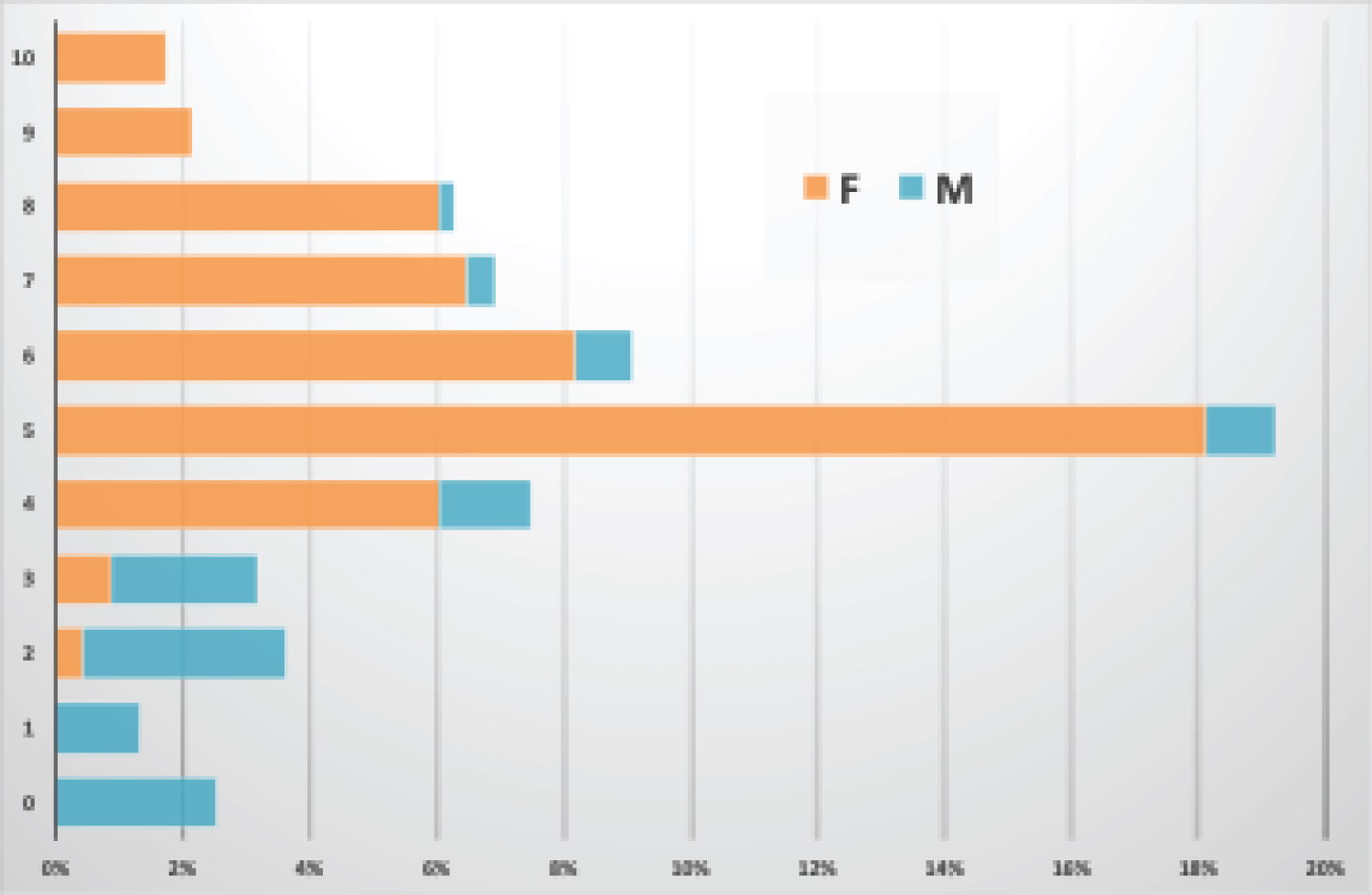

In the three years observed, 1140 first-year students from the degree courses in Nursing, Paediatric Nursing and Midwifery participated (males 20.4%, females 79.6%). 9.1% were non-EU international students. 63.6% had a regular matriculation age, while the remaining 36.4% were two or more years late.

Concerning social origin, 21.9% had at least one parent with a university degree, while 76.9 had no parents with a university degree, the remaining 1.2% did not answer.

71.7% came from high schools (8.4 classical high schools; 12.7 linguistic high school; 32.7 scientific high school; 15.5 human sciences high school; the remaining % from the artistic high school), 25.1% from technical and vocational institutes, while the remaining 3.2 had an undefined foreign qualification.

23.2% were student workers, and 39.7% were casual workers. Only 13.5% had a job consistent with their studies. About their job prospects, 85.5% said they enrolled in the degree course to acquire solid professional skills and the social utility of the profession they will pursue.

More than 45% of the students found the mixed teaching proposal exciting with a theoretical and experiential part at the Ethnomedicine Museum.

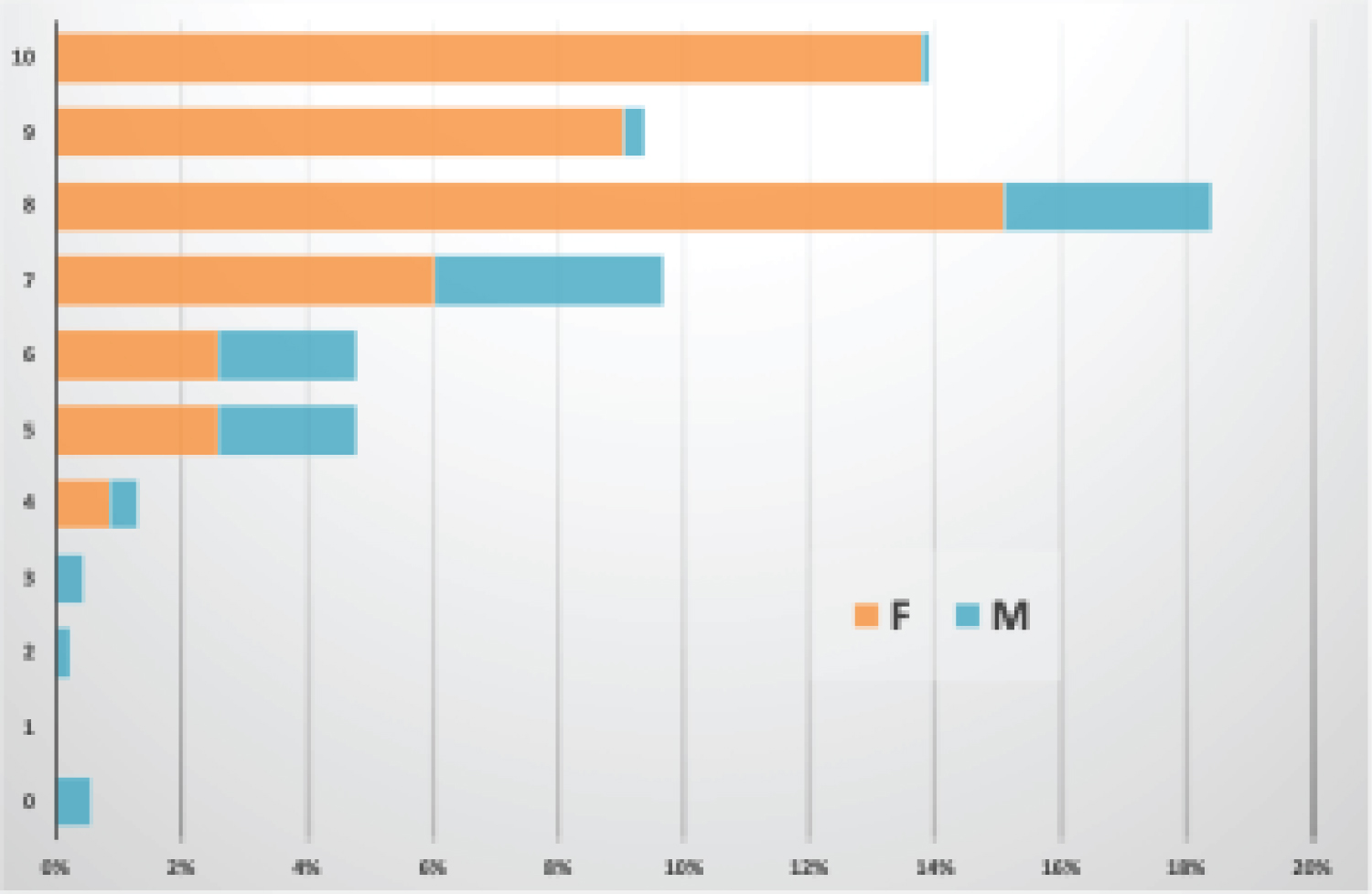

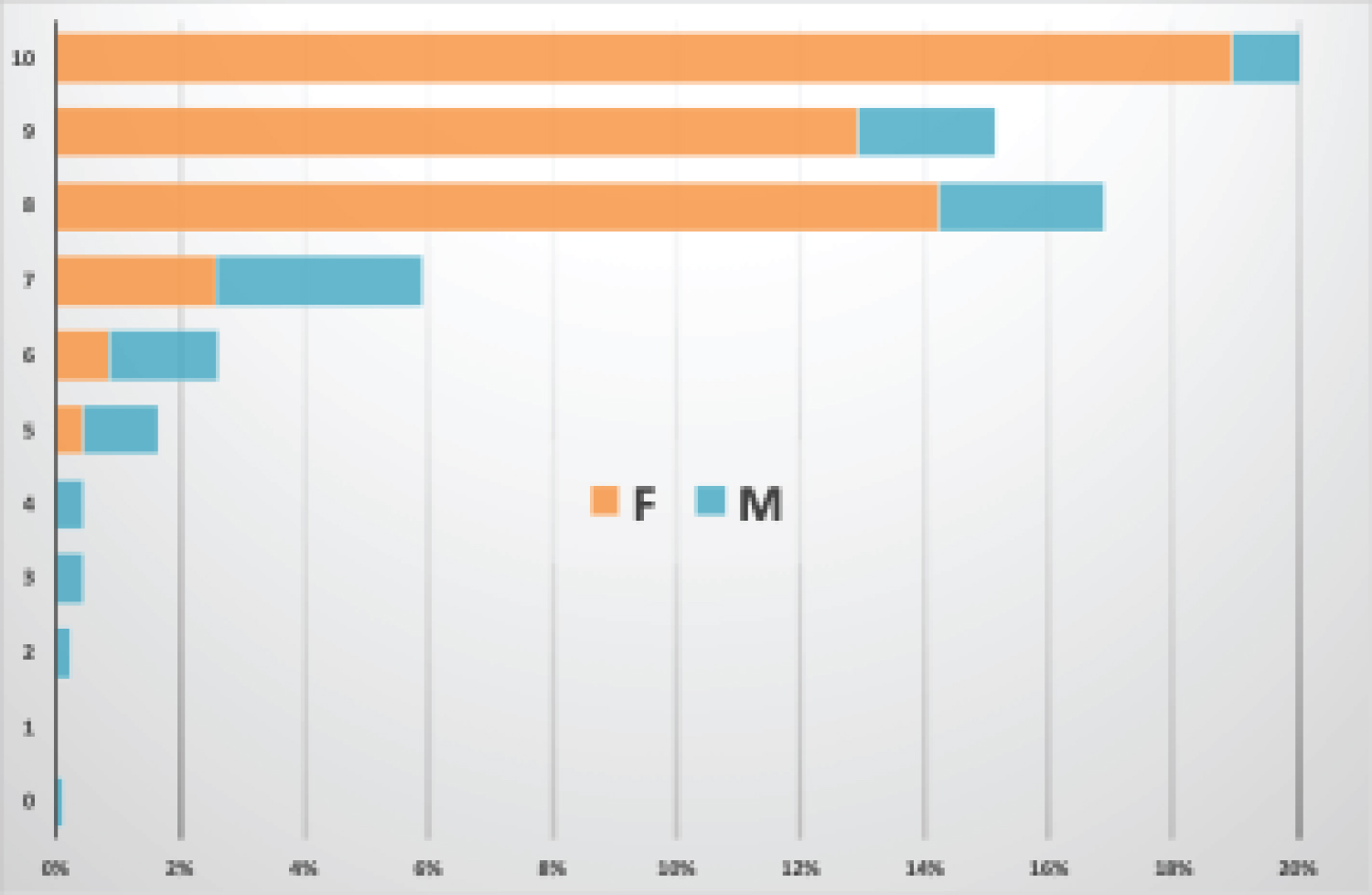

More specifically, Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the usefulness of teaching Health Anthropology in Medical School.

First, it emerges that males, although present to a limited extent in the courses surveyed, are decidedly less interested in an interdisciplinary and intercultural approach to heritage care and experience.

More than half of the students identified an anthropological view of care and health as necessary (Figure 2).

Most students agreed on the importance of cultural competence for the care and treatment of patients (Figure 3).

More than 19% of the students never experienced a lack of consideration of intercultural issues among health professionals (Figure 4).

The presence of a more remarkable lack of interest by students (mainly male) towards the activities proposed seems to be attributable to a more inadequate cultural background concerning the schools attended (mainly technical and professional institutes). From this emerges the need to extend an anthropological perspective to school education towards the other and increase the stimulus to enjoy the cultural heritage for improving knowledge and skills.

During the experiential activity at the Museum, several issues related to the applicability of traditional peoples' medicines in clinical contexts of Western medicine emerged. During the discussion between lecturers and students, it emerged that a high number of students (87%) are convinced that traditional healing practices will hardly find a place in this reality because current care practices, and even more so in the future, before being integrated into the clinical practice of hospitals must demonstrate scientific and empirical validity, characteristics that other medicines do not have so far. All the participants agreed that the attitude of governments towards other medicines would be decisive. Only if legislation opens the frontiers to integrating scientific medicine with other medicines will new horizons open, and scenarios could change considerably.

From the analysis of the answers provided by the students, a relatively clear picture emerges regarding the knowledge and interest that other medicines arouse in the surveyed student population. The most surprising fact concerns the transversal diffusion of this phenomenon. In fact, despite the different origins of the students, with different cultures, customs, and social peculiarities, all of them showed knowledge, even if superficial, and an interest in some traditional medicines of the peoples. Each has used them at least once in their life, considering them proper tools to cure some physical ailments, mainly to solve chronic physical problems and alleviate moments of general malaise (muscular-skeletal pain, chronic inflammation, allergies, etc., minor inflammatory conditions, infections of various kinds).

When asked during the museum visit and the experiential activity, "Would any of you be interested in working in this field? If yes, why? If not, why not?", the students stated that they were interested in other medicines and that they wanted to learn more about them, but only to increase their cultural background, to improve the relationship between the health worker and the patient and not given a possible job in the profession. According to them, in fact, other medicines are not scientifically proven and are not safe enough to be introduced in hospitals.

The reflection task, part of the third teaching module, was to be carried out two weeks after visiting the art museum. Two weeks provided sufficient time to process the experience. The outcome was an integral part of the students' summative assessment, aiming to obtain the expected university credit. This paper does not present it to focus only on the students' perception, free from the biases involved in formative assessment processes.

Interesting and discussed here are the reflections made by the students concerning the museum experience in medical education. They have been grouped into two main areas: the relationship between medicine and cultural heritage and cultural heritage to increase knowledge and skills in the medical area.

About the first point, students (74%) reported the effectiveness of visual stimuli to explore complex topics and pointed out that when looking at a work of art, it is as if time stops and there is space for questions, reflections, and thoughts.

Many students (87%) said they had learned that one should not stop at the first impression, even when confronted with an object. Furthermore, they suggested that this method of approaching things should always be used, especially in the health professions, because evaluating something or someone is a constantly evolving action and requires attention to detail. It is noteworthy that the students found that the exchange of opinions enriched their initial reflections with further insights that were verified in further discussions and insights. This made them think about how teamwork should be done.

Concerning the second point, students (77%) perceived the importance of working on the knowledge of care practices different from ours to put together a broader picture of the patient's situation.

The pilot study encouraged critical reflection on the crucial role of an intercultural approach to care mediated by material and non-material heritage, opening interdisciplinary and integrated teaching.

Discussion

For some years now, the process of 'humanising' Western medicine has been intersecting with the university training of health professionals. The progress that had distanced the doctor from his patient is now bringing him closer. The patient is once again the active protagonist of his own diagnostic and therapeutic pathway. The health professional is his privileged interlocutor, who guides him, listens to him with technical competence, culture, and humanity [16].

Several studies [23-26] and projects highlight the interactions between patients, culture, health, and wellbeing; few researchers address the issue of culture in the service of education. Silverman's [27] 'The Social Work of Museums' considers museums as places of inspiration and healing and proposes that museums can contribute to individual health in at least five ways: Promoting relaxation; immediate intervention to influence beneficial changes in physiology, emotions, or both; encouraging introspection; advocacy for public health; and improving health environments.

Students noted that not everyone sees the same thing when looking at objects and that seeing from different perspectives stimulates collaboration and communication. It emerges in the students' thoughts that an open mind and a willingness to listen to other team members help to improve understanding further, thus caring.

Culture seems so typical of human nature that it is taken for granted. We are so entirely shaped by a culture that we do not realise that it exists independently of us and that our actions usually reflect predetermined patterns and institutionalised dynamics. Any human expression cannot be separated from the particular cultural matrix of the society it belongs to.

We are used to a social context that is not very oriented towards the culture of otherness, and that treats all patients in the same way, without considering their different cultural backgrounds, in the name of professional ethnocentrism, which must be overcome by placing the person in his or her cultural context and designing care in such a way as to take this into account.

Two significant phenomena directly concern the world of health today: The internationalisation of diseases on the one hand and the cultural pluralism which increasingly characterises our societies on the other. Faced with the challenges of interculturality, it is increasingly necessary to move towards interdisciplinarity [28].

The need for art and science to be democratic and intercultural is stressed in many quarters. They are a valuable tool for broadening knowledge and understanding of the world, facilitating encounters with otherness, and thus reducing prejudice and stigmatisation towards those different from us.

Scientific collections, which over the years have performed educational and research functions by transmitting knowledge in a unidirectional way, are now increasingly becoming spaces for education, offering tools to decode and interpret the realities represented and opportunities to collaborate in the creation of content.

While maintaining a strong cultural and institutional role, museums in general, and scientific collections in particular, are increasingly rediscovering a social role: through 'heritage', identity is negotiated and shaped [29].

Museums conserve objects and testimonies on behalf of society, preserve historical memory for future generations and help to ensure equal rights and access to traditions for all peoples.

As a democratising, inclusive and polyphonic space, they foster critical dialogue about the future.

Therefore, the Museum is a prominent actor, which calls for responsibility, stimulates critical thinking, organises, and offers to support a conscious society. The purpose of the Museum is being redefined to welcome scholars, funders, owners of collections, and students, the community of citizens, the public, increasingly conceived also as potential co-curators of the contents themselves.

This is in line with the International Council of Museums' definition of a museum as an institution "at the service of society and its development" and the role that museums - especially those that hold ethnographic collections - can promote intercultural understanding and respect for others. Intercultural dialogue understood as a process that can stimulate an open and respectful exchange of views between individuals, groups and organisations with different cultural backgrounds and sensibilities, is fundamental in an inclusive society.

The trial highlights that young future health professionals are sensitive to experiences that do not focus their attentions exclusively on the techniques and practices of Western medicine but are curious to explore different worlds and ways of caring.

The museum visit within training in health anthropology was intended to be a learning experience using the ideas and concepts of Visual Thinking Strategies [30] and reflection. The outcomes of this experience were, on the one hand, the promotion of teamwork and attentive listening without jumping to conclusions, following Klugman, et al. [31], and, on the other hand, increased awareness of peoples' traditional care practices in line with Tullio Seppilli's lesson 'anthropology as a search in the very heart of society [...]. An anthropology to 'understand', but also to 'act', to 'engage' [...]' [32-34].

Observation and interpretation of art as a teaching tool can be used to develop communication and observation skills. The reflection task of the nursing and midwifery class confirms that reflection can be a powerful learning tool for a future health professional, as the internalisation of experience promotes understanding and can help future health professionals to provide more personalised care.

Conclusions

In this research, we wanted to propose heritage as a path to actively engage the student in the learning process. According to Lake, et al. [5], heritage experiences can stimulate the development of essential skills for the health professional, such as reflection and critical thinking.

Just as the museum experience can direct the audience to observe an artefact from different angles, so a museum relevant to the aims of the master's degree can help students develop not only critical thinking skills but also cross-cultural skills for understanding beliefs and practices of care that differ from placing and time and are all worthy of respect and consideration.

In a world such as ours, whose maps are constantly being redrawn by migratory movements and the presence of cultural otherness at the heart of Western societies, the challenge for medicine and the anthropology of health is to be able to engage in dialogue with local practices, but also to enhance a composite and articulated model of care.

A great help to the development of this idea is offered by overcoming the obsolete vision of the Museum as an emblematic space aimed at the consolidation of the values of the society and the identity that built them and at the transmission of unquestionable monologues. This vision allows to move around the capacity of museums to articulate discourses and suggest inferences and, therefore, to play the role of a platform for reflection on knowledge, beliefs, values, attitudes of the individuals that make up the society in which it is located.

A museum experience integrated with the humanisation of care teaching can be an essential part of the educational toolkit for health professions degree courses. It encourages the development of crucial skills for professional life, such as reflection or critical thinking skills; it offers a more open and inclusive view of other cultures and practices of care; it stimulates continuous professional development and a constant search for excellence.

All this needs to be done in line with the most recent WHO orientation that in the update of the objectives of the Traditional Medicine Programme has explicitly indicated the strengthening of interdisciplinary training and collaborative practice between practitioners of conventional medicine and practitioners of traditional medicine, to emphasise the individual [35].

References

- Wikström BM (2000) Nursing education in an art gallery. J Nurs Scholarsh 32: 197-199.

- Squires G (2005) Art, science and the professions. Stud High Educ 30: 127-136.

- International Alliance of Patients' Organizations - IAPO (2007) What is patient-centered healthcare? A review of definitions and principles. (2nd edn), IAPO, London.

- Engel GL (1977) The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 196: 129-136.

- Lake J, Jackson L, Hardman C (2015) A fresh perspective on medical education: The lens of the arts. Med Educ 49: 759-772.

- Nanavaty J (2018) Using visual thinking strategies with nursing students to improve nursing assessment skills: A qualitative design. Nurse Educ Today 62: 39-42.

- Staricoff RL (2006) Arts in health: The value of evaluation. J R Soc Promot Health 126: 116-120.

- Kumagai A (2014) From skills to human interests: Ways of knowing and understanding in medical education. Acad Med 89: 978-983.

- Spindler G, Spindler L (2000) Fifty years of anthropology and education 1950-2000. A Spindler anthology. Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey, London.

- Rivers WHR (1927) Medicine, magic and religion. Routledge.

- Kleinman A (1995) Writing in the margin: Discourse between anthropology and medicine. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Singer M, Baer H (2011) Introduction to medical anthropology: A discipline in action. Altamira Press.

- Inhorn MC, Wentzell EA (2012) Medical anthropology at intersections: Histories, activisms, and futures. Duke University Press, Durham.

- Jaspers K (1991) The physician in the age of technology. Raffaello Cortina Publisher, Milan.

- Leininger M (1978) Transcultural nursing concepts, theories and practices. Wiley, New York.

- Alici L, Danieli G, Manzoni T (2005) Humanities in medicine. S.l.: Il Lavoro editoriale.

- Guerci A (2007) Dall'antropologia all'antropopoiesi: breve saggio sulle rappresentazioni e costruzioni della variabilità umana. Lucisano, Milan.

- Rossi I (2003) Globalisation and multiple societies or how to think about the relationship between health and migration. Médecine et hygiène 2455: 2039-2044.

- Good B (1999) Narrare la malattia: Lo sguardo antropologico sul rapporto medico-paziente, ediz. Comunità, Torino.

- Lock M, Nguyen VK (2010) An anthropology of biomedicine. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Zito E (2017) Rethinking the 'marginality' of medical anthropology in Italy. Policies of resistance for all anthropology. Narrating Groups 12: 89-101.

- UNESCO (2013) Evaluation of the UNESCO internal oversight service of the convention for the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage.

- Ander E, Thomson L, Noble G, et al. (2012) Heritage, health and wellbeing: Assessing the impact of a heritage-focused intervention on health and wellbeing. International Journal of Heritage Studies 19: 229-242.

- Grossi E, Tavano Blessi G, Sacco PL, et al. (2012) The interaction between culture, health and psychological wellbeing: Data mining from the Italian culture and well-being project. J Happiness Stud 13: 129-148.

- Chatterjee HJ, Hannan L (2015) Engaging the senses: Object-based learning in higher education. Ashgate, London.

- Whiteley L, Tybjerg K, Pedersen B, et al. (2017) Exposing health and medicine as culture. Public Health Panorama 59-68.

- Silverman SK (2010) What is diversity?: An inquiry into preservice teacher beliefs. Am Educ Res J 47: 292-329.

- Rossi I (1999) Médiation culturelle et formation des professionnels de la santé - De l'interculturalité à la co-disciplinarité. Soz Präventivmed 44: 288-294.

- Lowenthal D (2005) Natural and cultural heritage. International Journal of Heritage Studies 11: 81-92.

- Yenawine P (2013) Visual thinking strategies: Using art to deepen learning across school disciplines. Harvard Educational Publishing Group.

- Klugman CM, Peel J, Beckmann-Mendez D (2011) Art Rounds: teaching students interprofessional visual thinking strategies in a school. Acad Med 86: 1266-1271.

- Seppilli T (1959) The contribution of cultural anthropology to health education. In: Barro G, Modolo A, Mori M, Principi, metodi e tecniche dell'educazione sanitaria. Atti del Primo Corso estivo di educazione sanitaria, Centro Sperimentale per l'Educazione Sanitaria, Perugia, 33-45.

- Seppilli T (2014) How and why to decide to "be an anthropologist": A personal case history in the Brazilian São Paulo of the 1940s, "L'Uomo. Society tradition development 2: 67-84.

- Pope C (2020) Tullio Seppilli: 'An anthropology to understand, to act, to engage'. Rivista della Società Italiana di Antropologia medica 49: 17-32.

- (2013) WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014-2023. World Health Organization.

Corresponding Author

Anna Siri, UNESCO Chair in Anthropology of Health. Biosphere and healing systems, University of Genoa, Italy, Tel: +39-328-4233341

Copyright

© 2021 Siri A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.