Covid-19, Isolation, Mammalian Dispersal Patterns, Urban Density, Social Distancing and Mass Psychogenic Disease

Abstract

Similarities between past Mass Psychogenic Disease events and mass behavior during the Covid-19 pandemic are compared. Isolation of mass populations in typically dense urban areas are examined as an unusually condition that could form initial stimulation for MPD. Psychological factors like uncertainty, confused political discourse, blaming of subgroups and minorities as well as rival political or religious groups could also be motivations. Conclusion of MPD events in the past are also examined and relation of the development of MPD in the past and parallels with the present. Social distancing and quarantine are not new methods to control and shape epidemics. Invented during the Bubonic Plague in the 14th century in Venice, the methods have varied considerably and human responses to isolation have been also numerous. These are similar to mammalian dispersal patterns in response to stress. In the current situation separation of workers from co-workers has taken place in a new context. Prior to the pandemic many individuals either lived alone or traveled long distances to families they typically spent little time with. This report draws attention to several emerging trends as a result of these conditions. Cities in history have reproduced cycles of urbanism, density, disease and dispersal. Current theories to modify density are aimed at reducing this cycle. Cultural Factors in transmission, government responses and time of arrival of disease are considered as well as SAS of populations and ethnicity. Behavioral responses to the pandemic have taken marked trends seen in past cases, including violence against minorities, attacks on medical workers and forms of denial and mass behavior against governments. Some pandemics in the past have manifested forms of mass psychogenic disease. As Covid-19 is just beginning to mature as a pandemic we might see the appearance of such mass illness. Human adaptations to pathogens and human caused changes in the environment have undergone dramatic change as has medicine one specific human response to disease.

Keywords

Covid-19, Mass psychogenic disease, Pandemics, Urban density, Isolation, Dispersal

Introduction

In recent years interest in mass outbreaks of behavior aberrations have brought renewed interest to the syndrome of mass psychogenic disease (MPD). Bartholomew, et al. [1-3] have focused attention on a subset of cases that seem to have environmental or toxic causation [4]. Many earlier studies looked at a variety of agencies, including fungus in grain and stress. One should consider that isolation and quarantine as well as people leaving cities for the countryside or suburbs are forms of general mammalian dispersal in response to disease [5]. Dispersal is related to a number of factors in mammals, including resource availability, predators and competition [6]. The main problem for humans is the apparent lack of an effective general dispersal pattern for modern populations. We have lost earlier hunter-gatherer dispersal patterns with urbanization and food production. Lack of dispersal patterns seen also in other social animals (e.g., some insects) may be a consequence of eusociality.

Some research was aimed at outbreaks of violence in prisons [7,8]. Isolation in prisons seems to result in depression, psychosis, other mental health problems and physiological problems. Hysteria in factories (e.g. two incidents in the south of England, see [9]), especially in parts of Asia where factory work, unfamiliar situations, isolation from family and the demands of sweatshop conditions seemed to have considerable effects [10].

One must consider that living in dense urban conditions is new to our species and has only a history of less than 10,000 years and for most human activity, less than 2,000 years at best. States and nations have lifespans of about this age and what is called civilization, around this length as well even using ideas from Jasper [11] or Toynbee [12]. The point is that our urban lifestyles are fragile and though nation states collapse and are often seen to transition to new organizations (see Yoffee and Cowgill [13]). We can ask if humanity has learned its adaption to urban life and if that learning is affected by pandemics or if a long period (undefined) of isolation will affect that state of that learning? Hominoids, our ape relatives are not highly social, and chimpanzees only slightly so. If we compare ourselves to the eusocial insects and examine the effects of their pandemics, the scenario is troubling. Colony Collapse Syndrome is thought to be spread by a pathogen and magnified by stress [14], the outcome is the end of social life for colonies across the globe. Human children learn social life in the context of their environment, if that environment is as limited as quarantine has become, what effect will that have?

The mass media is publishing articles speculating on the possibilities of violence and disorder due to the isolation and stress of the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g., Hertz [15]).

In one of these, Noreen Hertz writes on social isolation, depression and aggression [16]. She cites experiments with rodents on the relationship between social isolation and aggression (likely referring to work by Fone and Porkess [17]), suggesting that isolation is the cause of aggression in mice. She then generalizes this conclusion to human experience, specifically Covid-19 isolation, urban living, depression and right wing politics. The missing context is that in the rodent experiments she refers to, the social isolation is from birth and like the, Dodsworth and Harlow [18] experiments in the 1950s and 1960s with macaque mothers and their offspring, what is missing is any social experience and learning. Obviously extrapolating from rodents to humans is problematic, but equating the pathological condition produced by complete lack of social training to contemporary human life is more than distorted. Yet there is evidence of disease production related to isolation [19].

Isolation's effect on social credit is negative, reducing a store of association based on familiarity, conditioning rewards and fraternity over time. This reduction leaves people without a foundation of real experiences to draw on to allay feelings of loneliness and depression. The ultimate consequences of which is a rootless reference point for emotional interpretation. As Kelly [20] found, people construct their identities from their social experiences and without continuous references they can fall into the chaos of Laing's "false self" identity [21]. This can be the foundation of social psychosis and lead to scapegoating, violence and disorder of a mass scale. Noreena Hartz [15,16] has made this connection regarding modern life in a recent book, centered on the production of depression, loneliness and loss of identity. As she makes numerous references to Durkheim's theories of society and the individual, one conclusion that could be made from Laing and Durkheim [22] is that whereas the individual can find the "false self" in such control that the real self is "murdered" or a suicide, in the social context the individual is so divorced and alienated from society they become exiles and society an enemy, the meaning of their detachment and suffering.

While there is considerable literature on the creation of human atomization as a result of urban housing and city design, the outcomes are usually associated with depression and suicide. Jane Jacobs in her famous book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities [23] demonstrated how streets in the same city, populated by people of similar backgrounds and incomes could be either safe or dangerous. I have favored congregate living over single unit housing (see my book, An Ethnography of the Goodman Building: The Longest Rent Strike, [24]), The nature of contemporary urban landscapes seems to promote depression, but not more aggression when we factor in increased density and population per square mile. This problem of density was mentioned in the recent Financial Times article by Jonathan Wheatley (Pandemic forces rethink by city planners in emerging nations, Sept 23, 2020) [25]. Concerns about health in living in cities and the design and location of cities, has been a topic of discussion for well over 2,000 years [26-28]. The problem of hollowed out modern cities of the Covid-19 pandemic are being approached with 20th century ideas of reinvigorating suburbs and reconceptualizing sprawl [29]. This does not bode well for sustainability of energy or pollution unless drastic changes in energy production and consumption are made.

Ms. Hertz addresses also the stress of the pandemic as well as isolation and here we get combinations of stimuli that relate to increased likelihood of aggression as reported by Xian-cang Ma and colleagues in 2011 [30]. Stress, depression and isolation create uncertain conditions that seem to promote conflict. In my study of human behavior during past pandemics (Caldararo, Niccolo, Evolutionary Aspects of Disease Avoidance, [31]) we do find an increase in violence as well as burning, victimization and mass migration, as in the remarkable European flagellants who, by the thousands, marched across parts of Europe during the Black Plague. But in these cases of chaos the main factor was a lack of strong institutions and government. Today if there is any parallel it is in the attacks on medical institutions like those of the Trump administration on the CDC and the failure to produce unified government organization to repress the disease.

During the Middle Ages mass events, like the movements of large populations of the flagellantes, kissing nuns or manic dancers were explained by possession or other religious causes. Mass events among colonists, especially in the Americas and most famously in New England with the Salem witch trials attracted some attention from researchers [32]. This last example has some parallels with today's Covid-19 social distancing guidelines in producing a reduction of contact between individuals used to constant interpersonal contact in densely population urban zones.

In the Salem example, we have people transported from one nation and culture thousands of miles to a location unlike that of their home environmental and cultural training. They also were limited in contacts from the normal situations of their home milieu. The cramped ship journey and immediate strange colony and unfamiliar populace, were preconditions of psychological trauma. While lower population density was possible they were hemmed in by a relatively unknown and often hostile enemy largely unseen most of the time. They were assaulted by disease and low food availability. The uncertainty of the situation might be seen as similar enough to use as a laboratory for studying Covid-19 and a number of populations around the globe. In Salem, the colonists turned on themselves, today with Covid-19, like many epidemics of the past, the targets are foreigners, minorities, doctors and government.

Past Examples and Present Course

Physician and bacteriologist, Hans Zinsser, wrote in his book, Rats, Lice and History, that the appearance of a new disease was like an invisible animal, one could not see it, but it could be known by the effects it had on its environment. Since 1935 when the book was published, we have come to know more about diseases, their causative agents and their natural history. One aspect of the "life" of disease is how it comes to adapt itself to hosts to survive and replicate. Since, as Theodore Dobzhansky [33] put it, "nothing makes sense in biology except in the light of evolution," so with Covid-19. It is a virus that has evolved and invaded a new host, adapting its biological functions to humans. In this context, we also know from the work of evolutionary biology in disease, that pathogens evolve over time to become more or less virulent. Once it was thought they always became less virulent, a logical idea based on the premise that pathogens would adapt to hosts and become semi-harmless chronic infections. Why kill the host was a general refrain. Paul Ewald undermined this scenario in 1993 with his book on the evolution of disease [34].

So, if we use this background to look at the current Covid-19 pandemic we cannot predict the outcome of the disease. SARS and MERS, two coronaviruses behaved differently as pandemics, and coronaviruses in particular are quite varied. Will Covi-19 disappear like SARS or become endemic like MERS [35]? Will it return year after year like the flu or return in waves of lessening strength over centuries and then disappear as a pandemic like the Bubonic Plague? The Plague is still with us but seldom affects many people [36,37]. It is believed the bacteria that caused the disease has mutated or the most susceptible populations have died off, conditions have changed and also treatment for the infection is rather effective [38]. Pneumonic plague was the most dangerous as it could be spread from person to person, otherwise the bacteria was spread by the bite of fleas, other forms being septicemic plague and bubonic plague all caused by Yersinia pestis bacteria.

Here we might have learned something from plague for Covid-19. Plague adapted to close conditions of European medieval cities and became the pneumonic plague. Medieval populations of Europe responded to plague by a number of behaviors, fire, killing infected people, running away to the country, quarantine and mass troops of people wandering over the countryside beating each other with chains, etc. and other forms of religious devotion. Today we are seeing many of these same mass behavior patterns in response to Covid-19. What is also worrying is the general impatience people are demonstrating with social isolation techniques and the economic disruptions. It is unlikely the epidemic will be over this year, as many politicians argued in the spring. Some scientists projected from other viral pandemics that it would taper by summer with warmer weather. That also has not taken place. Some suggested a second wave as in the 1918-1919 flu, perhaps even this fall in combination with the fall flu season. This is becoming increasingly likely, yet figures already seem to indicate a second wave now and it has been argued the 1918 - 1919 flu had a third wave [39] which appears possible for Covid-19 [40]. Efforts to produce a vaccine or a cure are gaining significant funding and government energy, yet the products of this work are likely to be months, if not years off. And, like the common cold, Covid-19 could become recurrent, like the flu even with a vaccine.

Changing Nature of Disease and the Natural History of Infectious Agents, Changing Human Response and Behavior

Pathogens and their hosts are in a constant war to achieve either elimination or adaptation. The host marshals defenses and attacks with its immune system and the pathogen attempts means of avoiding destruction and maintaining its presence and the production of progeny using the host as a resource. This is an evolutionary struggle and humans, as primates have the residues in their DNA of many past battles and wars waged [41]. The diversity of our Major Histocompatibility Gene Complex or System (MHC) evolved long before the appearance of humans [42]. It is evidence of the complex interrelationships of pathogens of hosts, to the point that Woolhouse and associates [43] show a co-evolutionary pressure between hosts and pathogens. This includes CRISPRS and other anti-viral systems [44]. Some of our endogenous retrovirus sequences are evidence of this as is the structure of our main antibody machinery, the V(D)J recombination system (of the adaptive immune system) appears to be derived from a transposon [45].

Some diseases, by the effects of the infective agent like a virus, can change or otherwise affect the behavior of its host [14,46]. This relates to the "Dancing Manias" of Europe in the medieval period to the 16th century believed to be the result of human infection with wheat infected with ergot a mold related to LSD [47,48]. Mass human behavior has been described as pathological under the term, mass psychogenic disease, or epidemic hysteria. Some separate it from examples of mass or collective delusion; others use the term mass psychogenic disorder [2] or speak of mass psychological events [49]. Some cases are thought to be the result of poisoning or infection producing strange smells, tics, headache or vertigo. Neurological effects of Covid-19 infection are diverse, yet persistent smell, loss of smell, foggy thought processes, delirium, are a few of those reported [50].

Mass Psychogenic Disease and Social Disruption

There is no doubt that Covid-19 has had a major effect on human society since January of 2020. The disruption in economic life as well as religious activities, recreation and family have been of such magnitude that some social scientists have suggested that the aftermath will result in human society being fundamentally changed (e.g., [52-54]). The disease spread at a time a significant political disruption, from Brexit and the election of Donal Trump, to Black Lives Matter demonstrations as well as others across the globe related to populist movements. Social upheavals are often related to changes in the environment [55,56]. The combined effects of human political and economic uncertainty, climate change and Covid-19 should be seen in the background of past plagues and revolutions.

Assessments of past Mass Psychogenic Disease argue this illness only appears in closely related populations or those in similar situations and the illness spreads very quickly and dissipates fast [57]. Examples of this are also described as hysterical or irrational, but these descriptions often are laden with judgments of the particular outcomes. Nazi Germany can come under such a term, or the Salem Witch Trials, mob behavior where victims are produced often of minorities or certain classes or castes, as in lynching of African Americans [58]. These last examples are the consequence of the social disease called racism [59]. Malinowski [60] was perhaps one of the first to compare Nazi scapegoating and persecution, and that of the search for hidden communists and Trotskyists to witch hunting.

With regard to mass political movements, setting aside the complexities of revitalization movements, those like Nazi Germany can come to express the conditions of a population in terms of depression and anomie, the loss of cohesion as values and goals of a society appear to collapse. Recent studies have supported the idea of suicide and depression in both America and European countries [61]. The association of isolation, depression and the development of detachment from values and goals can create false-self construction in some cases of psychopathology according to some psychiatrist like Laing [21]. The false-self lives within a world dominated by childhood conditioning of repression and becomes over time a projection of the reality of the individual. Here the background of Donald Trump and Adolph Hitler show parallels, especially in the father figure and history of projection of persecution of contaminating or corrupting influences (Jews, Mexicans, FBI, IRS, etc., see Langer, [62]). The nature of the particular individuals is not as significant as the movements of people they create and represent. Trump, like Hitler, has been able to project his image of reality onto millions of Americans, though their individual psychological condition may be the consequences of real economic and political factors, they are unreal in analysis (deep state, for example, see Rohde, [63]). In the current situation with Donald Trump, his individual pathology seems to have linked to the mass dissatisfaction with life, expressed by millions as depression [64]. The ability to recruit and motivate masses of people to the purpose of eradication of a false-self world (e.g. attacks of "brown people" deep state actors), while seeming ludicrous, could be as dangerous of that of Hitler's. Defining both the Nazi movement and Trump's as potential mass psychogenic disease states, can only be born out, unfortunately, by time and the development of Trump's presidency. His infection with Covid-19 could make him even more unstable given some of the after effects in patients [50]. It is a magnification of what Eisenstadt [65] called "charismatic" authority. Should he cancel the election, or deny its validity and force a Constitutional crisis we would find the possibility of mass violence by his followers. Then, the persecution complex expresses itself as a destruction of its enemies in defense of the false-self image of reality. The outcome for Germany in the 30s was Nazism, for America in the 2020s could be worse. When the anti-self reality forces itself on the false-self, as in Hitler's case, the response was Armageddon, total war without end. What Trump's response is likely to be is more concerning for all given nuclear weapons.

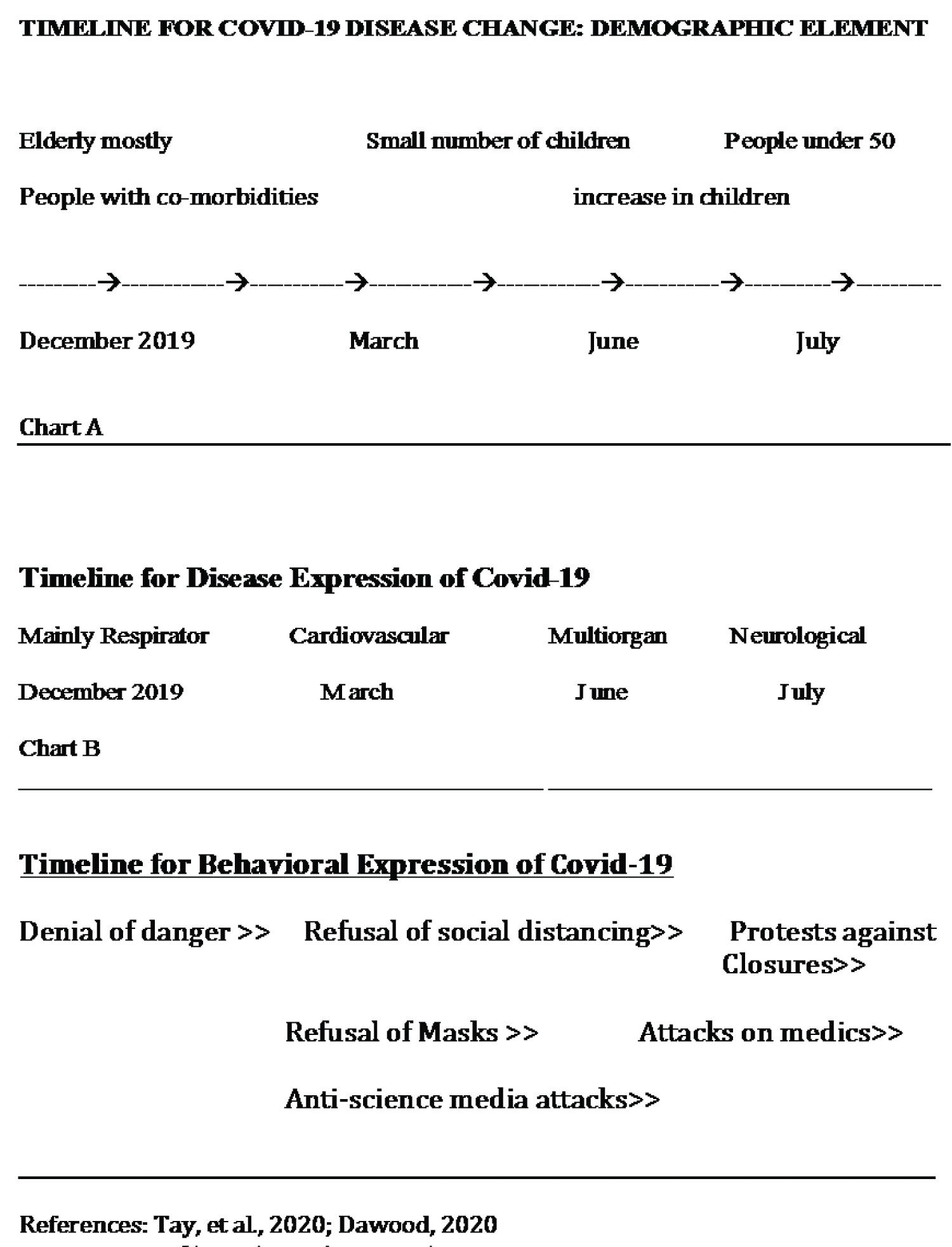

The natural history of Covid-19 and its evolution in context of human responses can be conceived in Charts A, B and C below. There is disagreement regarding the course of Covid-19, with some specialists arguing that the disease is producing fewer lethal cases and others suggesting that the death rate is reducing due to better treatments, younger infected cohorts of the population and more testing [66] (Figure 1).

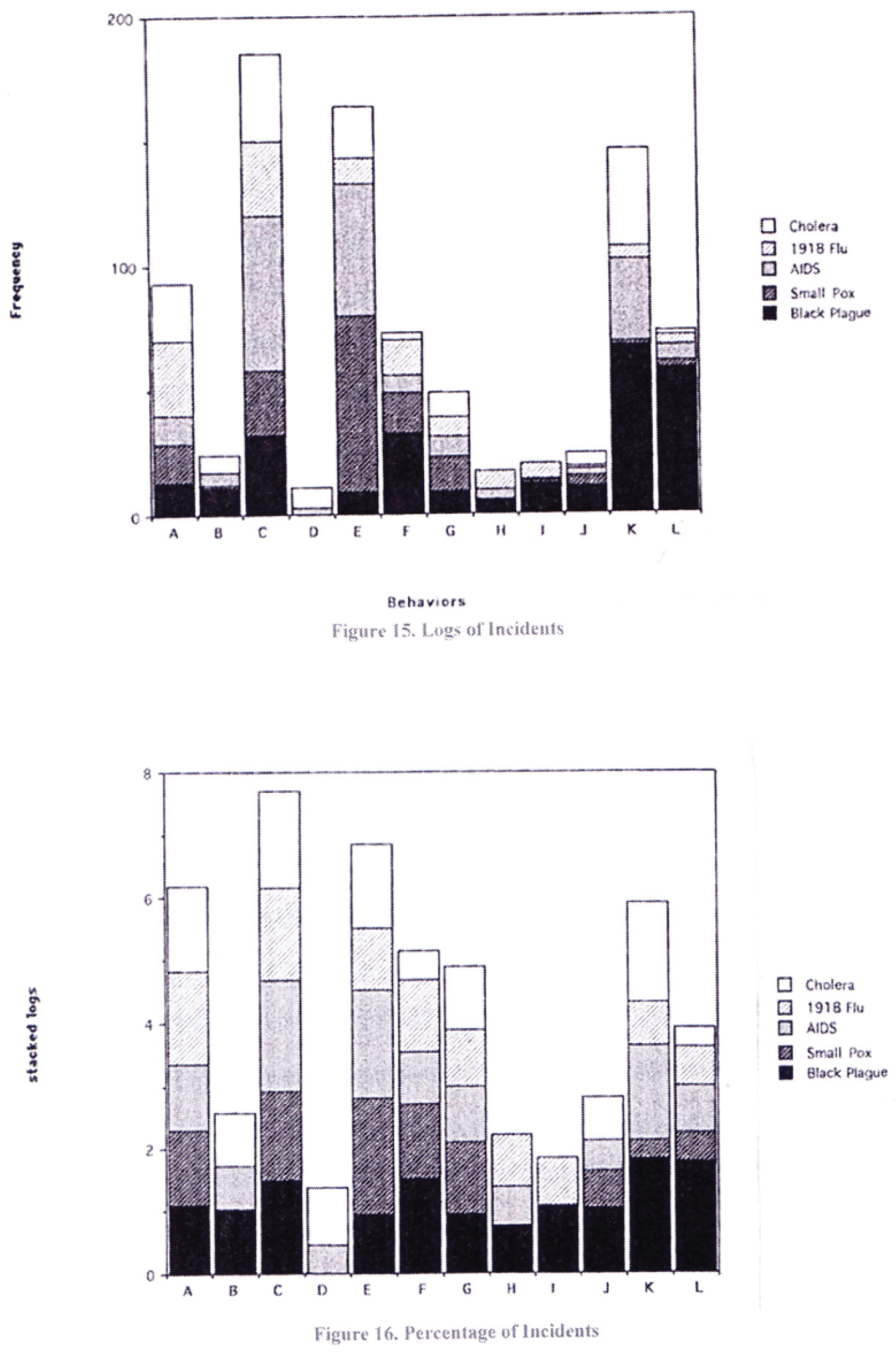

In many of the MPD outbreaks we find mass behavior of a number of manifestations and type as well as frequency of event. Manic dancing and violence against minorities are often seen combined [31]. The fanatic behavior of the colonists of New England reached fever pitch in attacks on individuals, public terror and trance as well as convulsions and public trials, punishment and execution [67-70]. Relieving the terror of uncertainty was exhausted by a combination of public intervention of religious figures (not always successful), public trails and violence. As long as the civil authorities were divided and unsure, the panic spread and intensified. Once it was unified and public displays were used to justify statements of an end to the threat, the panic ended.

Current reports show little violence against infected individuals or minorities, though some anti-Chinese behavior has been reported [71]. However, one should keep in mind that data from past epidemics charted in Caldararo [31] are based on time factors, which covered the entire course of the disease. Covid-19 has just begun and some patterns are appearing new and varied in some locations, for example, Mexico where attacks on patients and staff have occurred [72,73]. On August 5th of 2020, Mello, et al., reported increasing attacks on health workers across the USA. Worldwide attacks are summarized by Devi [74,75].

Rasmussen, [76] discusses the unprecedented attacks on public health officials and mainly the independence and integrity of the Centers for Disease Control.

In like manner, we have seen the Covid-19 pandemic spread over the globe with considerable rapidity, causing fear and uncertainty throughout the general public as well as the medical community and our political and religious institutions. This uncertainty and fear induced large-scale disagreements among the population, political leaders and religious and medical organizations. At approximately the same time we saw mass movements of an unrelated nature breakout across the world aimed at achieving justice for oppression and discrimination. These mass movements were often associated with violence and widespread destruction of property in similar patterns in a variety of developed and underdeveloped nations. This association in no way diminishes the relevance or legitimacy of the demonstrations, but only notes the fact of the timing and the violence produced.

Coronaviridae, Infection, Adaptation and Treatments (Old & New)

Treatment of patients with SARS was limited, usually including antibacterials, an antiviral and methylprednisolone [77]. This last is parallel to use today of corticosteroids [78]. However, since the SARS agent is a coronavirus search for cures took on the character of the virus. One possible means of prophylaxis came from a report in the Annals of Internal Medicine [79] where Dr. Sicore of Buffalo General Hospital noted that patients treated with cimetindine had few colds. Dr. Goldstein noted the effect of cimetindine on Epstein-Barr in the same year [80] and on genital herpies by Dr. Wakefield in 1984 [81]. But success in developing cures or vaccines for viruses has been poor indeed. With the exception of Polio, treatments for others like Hepatitis C and HIV produce chronic illness not cures. Claims for broad spectrum anti-virals have fallen short in practice (e.g., [82,83]).

There has been much discussion of "superspreaders" of the coronavirus responsible for the disease, both during SARS and now. However, emphasis is now being applied [84] on "super susceptible" those individuals who are most liable to infection and serious complications from the infection. Such variability initially focused for Covid-19 on the ACE2 receptor [85]. It is clear from the epidemiological evidence on SARS that while many people who had contact with infected patients in hospitals and hotels in Hong Kong and Toronto became infected themselves, many of those with intimate contact, including family members of some of the initial cases did not become infected, as noted by Klaus Stohr, WHO virologist on April 18th in a Washington Post interview. Household transmission, even of health care workers, varied depending on the isolation and sanitation intensity [86]. Use of a mask alone seems to provide a weakened exposure and allows a more protective response to infection [87].

Stohr also noted the relationship of the virus with certain characteristics of its survival and transmission; for example, the virus survives longer as acidity decreases in diarrhea and survived well in extreme temperatures [88]. This would seem to argue against an effect by H2 blockers, but the effectiveness of these agents (and Sicore notes the effectiveness of ranitidine as well) may not be in the specific action in lower acid production. Such a conclusion seems possible from work by Mezey and Palkovits [89] where it was demonstrated that the targets of antiulcer drugs appear to be cells of the immune system and not parietal cells as previously believed. Though results published by Diaz, et al. [90] and Fukushima, et al. [91], contradict these findings though not the knowledge of the intimate localization of immune cells in the gastric mucosa [89]. Cells active in the lamina propria of the gastric mucosa include lymphocytes, plasmocytes, mast cells and macrophages. Mezey and Palkovits [92] used immunostaining to identify the presence of these cells and found they were all distributed homogeneously throughout the lamina propria. Their results indicated that H2 blockers acted on immunocytes and these cells act on epithelial cells. While other research supports the idea of such interactions [93], the intimate association of these cells and action by H2 blockers may be a vehicle for protection from certain infections or act to augment them. We might assume that a secondary effects of these drugs (including famotidine and ranitidine) and related action by the H2 agents modulates immune cells in ways as Ghosh, et al. [94] summarized that reduces the potential for infection by certain viruses including SARS-COV. Cimetidine and ranitidine might act not as cures but as a means to reduce the susceptibility of some percentage of the population to infection or serious disease. However, treatment of patients with Covid-19 has resulted in ad hoc uses of multiple drugs and initial information on cimetidine reported its negative effect on the use of hydroxychloroquine [95]. Early in the pandemic a small study suggested famotidine had beneficial outcomes in Covid-19 infected patients [96]. This study was the Malone, et al. [97] preprint. One problem with the early reports of efficacy was the fact that many practitioners in hospitals, and especially with some of the sickest patients in ICUs were using multiple drug approaches so determining the one that was most useful was difficult. Shang, et al., report on how Chinese researchers and clinicians cooperated to organize treatment modalities at a number of hospitals to discover the most effective approaches [98]. Early reports of efficacy have been usually followed by controlled study results showing little or no effect or only under certain circumstances, as in the case of convalescent plasma [99]. Response to the pandemic has unfolded in a crisis of health care that has forced the medical community to respond in unprecedented fashion joining university departments that have diverted research to the virus with clinicians [100]. In a prescient paper on drug research and Coronaviridae, Totura and Bavari [101] summarized the available drugs and experiments with animal models, as well as approaches to neutralizing members of the virus class, producing treatments and vaccines.

In 2003 testing for SARS found only 40% of cases positive with a declining number over time [88]. This seems to parallel Covid-19 but with an added confusion of a lack of international cooperation and standardization [52].

In an interview with Geoff Dyer of the Financial Times (25 May 2003), Dr. Tony Fauci suggested that the virus may become a seasonal problem, like that of flu. Given the return of the 1918-1919 flu in several waves, this could be a prediction of possible recurrent epidemics of SARS. Of course, the 1918-1919 Flu may have had an earlier arrival in 1896, according to Knapp [102] Recovery from Covid-19 has produced varied outcomes, from neurological deficits to continued pulmonary and energy problems according to a number of reports [103]. Like many modern diseases (e.g., AIDS, Zika virus, herpies) lingering effects can produce chronic disease symptoms [104,105]. Along with increased numbers of people affected with forms of dementia and rising numbers of diabetics (including increasingly younger cohorts) the way modern humans live is producing mounting liabilities.

Questions of how long the virus can survive in an infected person's body after recovery have been complicated by suggestions of reinfection or reappearance of the virus and symptoms. Covid-19 could then become a chronic disease like AIDS or herpies that can reassert itself depending on the state of the immune system of the host [106]. It was noted in the early stage of the disease in Hong Kong from Dr. Lo Wing-lok an infectious disease expert there in an Associated Press interview, that many of those who died had a rare airborne form of the virus chlamydia as well as the SARS agent. This has been found again with Covid-19, coinfections and co-morbidities seem quite significant both to infection and disease progression [107,108]. Thus individuals susceptible to the syndrome may be victims of dual infections seen in AIDS, or superinfection conditions [41].

Changes in Human Behavior and New Forms of Family and Work

Current restrictions on work environments have left many people separated from their jobs. This creates several changes in life style. First, the work environment provides individuals with both an income and a sense of worth. Second, the interaction with people at work, typical experiences with others like baristas, lunch staff and support crew are reinforcements of social capital where individuals experience generally positive rewards. Thirdly, many people invest considerable emotional support in co-workers, in some cases this has been expressed as pseudo-kinship in a number of forms, for example, the "work spouse" [109].

In reports in past epidemics families were often trapped in their homes and refused the freedom to exit by authorities. We have good evidence from both Europe [110-114] and the Middle East [115] and ethnohistorical evidence regarding this practice [31]. Often people were aided by authorities if suspected of infection; sometimes they were attacked or driven out. Generally social institutions guided and framed the specific kind of treatment and the responsibility of individuals to act in accordance with rules regarding avoidance. We also have substantial evidence of very heavy population losses from a number of plagues, like Bubonic from 1346 to 1600 C.E. with substantial return of normal life and economic growth even in the context of wars [116].

The freedom of movement and reinforcement of habitual contacts of friends family and workers, can be seen as the framework of normality that maintains social cohesion. A breakdown of such normality, as in war and disease can have significant consequences on the mental health of a population and on the stability of a social framework. Experiments with isolation of individuals often report psychological pathology and this includes incarceration of individuals in prisons. Recent research has focused on the elderly and outcomes of social isolation and the onset of dementia [117]. Alarcon [118] has addressed the potential for long-term effects on the mental health of people due to the lock down and social distancing required to fight the Covid-19 pandemic. Fears of contact, of contamination of surfaces, of transmission in the air have increased tension. It has been reported in the recent past that bacteria and other pathogens can be spread by bathroom hot air hand dryers [119].

Usher, et al. [120] have looked at the current context of Covid-19 in relation to recent pandemics and noted the similarity of long-term effects to PTSD. Long-term developmental or behavioral problems in children do not seem to be prevalent on experiences in social isolation in early life [121]. Such outcomes are related to family situation and the current Covid-19 effects are greatest in lower income and ethnic groups, especially those with extended families so the pressure on family life can be expected to be a significant factor [122,123].

Background of Trouble in Stay-at-home-Covid-19

Today we find the general populace in significantly different contexts due to the change in the nature of modern work, family and associations. People commute for several hours according to the United States Census Bureau [124]. By bus, car, train or plane the U.S. commute is characterized by an average of 26.1 minutes with many metropolitan areas showing over an hour. This means that the average commuter spends at least an hour in transit and 8 hours or more at work. For couples or families this can create serious problems of association, especially if the adults work different shifts or hours. But in general it means that many families spend little time together. In the industrialized world this has progressed from people working 14 or more hours a day in the 19th century. But they often still had some substantial social support in extended families into early 20th century until the advent of the 8-hour day, where it was relieved to some degree [125,126]. Then we come to the flight to suburbia in the post-WWII period during the great effort to provide adequate and standardized, safe housing [127]. This led to the characteristic isolation and psychological conditions critics attached to such developments as Levittown [128]. But Gans [128] disputes the isolation and "wasteland" idea of these developments and his research shows substantial neighborhood organization and satisfaction by both women and men. The idea that these communities created as supportive systems as the extended families in the central cities is questionable but convincing data supports his argument. But this concept of vibrant communities united by extended families or neighborhood friendships creating foundations for social capital is appealing. My research in the town of Fairfax [129], a hamlet founded by dam workers and laborers in the 1930s, shows a similar environment of families helping each other for more than 3 generations. Handlin [130] makes a similar argument in attempting to compare life in European villages that people left to urban conditions including slums and suburbs where they immigrated or their children grew up.

Later, as more women entered the workforce, especially in response to the stagnation of wages after 1970, we found children attending to themselves as "latch key" kids. Derber [131] has linked the demise of unions, wage stagnation, off shoring of jobs, single parent families and two paycheck families with decreasing community and increasing violence. Today 75% of mothers' work, nearly comparable to data from 1900 show 20% of mothers worked and 40% of foreign-born women worked and were household heads. Today more than 70% of all children live in a home where both parents work [132].

A telling consequence of the economic shutdown and social distancing has been the increase in child and spousal abuse. In the UK information on the victimization is gathering and a mounting wave of suffering appears to be coming to the fore [133]. How to stop or reduce this feature of the shutdown seems to be lacking and efforts instead, in response to political unrest to open business in America appears to be leading to a premature opening and end of the virus-transmission limits. Yet reports of crime yield worldwide evidence of reductions across nations and regions [134]. Explanations of this drop are linked to social distancing and restrictions on movement, yet many people have difficulty gaining access to food and food banks and charities are pressed for resources. Whether this will result in more infection as appears to be the case in Sweden with its refusal to pursue these methods is unclear. Whether a second wave as in the 1918 flu [135] will occur and be so terrible that all this debate will be seen as so much confusion and waste is yet to be seen but is suggested by the Director of the CDC [136]. Other aspects of urban living are under stress, the food chains that stretch across the globe are failing and even food banks in developed countries running out of supplies. Among the poorest, especially in high concentration population areas where nations policies have made transportation difficult many of the poorest are stranded and without access to food [137].

Already by late April Sweden's Covid-19 numbers are twice those of nearby Denmark that instituted a closure (https://www.statista.com/statistics/1102203/cumulative-coronavirus-cases-in-sweden/). However, since Sweden's population is nearly twice that Denmark these figures seem to show that lockdown or increased infections, the effect is not resulting in any change in policy. Norway with half the population of Sweden has about one-third the Covid-19 cases as well [138,139]. Yet by September 2020 Norway's numbers had dropped significantly compared to Sweden with only 15% of Sweden's [138]. Finland had achieved not only very a very low rate of infection, but also a significant economic recovery [140]. This was due to both long term planning and investments in health infrastructure and government agency cooperation. In such considerations we should keep in mind that the Covid-19 as a disease and pandemic is not over, we do not know its course through the human body (natural history) nor its ability to evolve. Also, as Mols [116] found from a detailed examination of population and economic records of the 16th and 17th centuries, recovery of both took about a century. Current estimates by the IMF (International Monetary Fund) [141] are much rosier, which is most likely prudent given we do not know how the pandemic will unfold yet. In June of 2020 the IMF projected a minus 4.9% growth with a return to positive growth in 2021 of over 5%, by October the negative growth projection had risen to -4.4 % but the 2021 recovery had climbed to only 5.2% [142]. The pandemic is also having a challenging effect on economic theory, where during the 2007-8 credit crisis theorists like Carmen Reinhart had argued for austerity and a reduction of credit, now are reversing opinions are pushing for more debt on nations' central banks balance sheets [143]. During the crisis I was one of a few who argued for more credit and against austerity [144,145].

The difference in comparison with Singapore may be the nature of the immigrant population, mainly its housing status and the access to healthcare. The choices between Sweden and Norway, and Denmark may be cultural, in patterns of belief of interpersonal contact [146] as well as approach to sanitation and cleanliness [147,148]. Denial of disease or its danger is also seen in Brazil [149]. Africa is another separate case in the estimation of some demographers due to its population profile with a small elderly population. Given the high rates of infection of Somalis abroad and African Americans this may prove mistaken [150], and recent assessments imply significant increases [151].

Japan is another special case where closure has been limited even though Japanese scientists and health officials produced an early report on asymptomatic carriers of the disease [152]. Japan reports less than 5% of Sweden's rate (total of 14,088 cases) but only tested in the spring less than a tenth of the number that Sweden has (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/?utm_campaign=homeAdUOA?Si). Japan, with a population nearly ten times that of Sweden, is also not in total lockdown and business is largely operating normally. A state of emergency was made on April 7th but closures of schools, public gathering and business closures have been late as infections continue to rise [153]. Japan's spring rate therefore may be an artifact of low testing and limited testing areas. By August Japan saw a significant "second wave" of infections, but recent new controls seem to have reduced new cases [154].

Cultural and Urban Factors

Mass Psychogenic Disease is a varied condition that seems to be initiated by a variety of stimuli and agents. The infection of animals with pathogens has been found to produce behavioral changes, both long-term and short-term conditions. But cultural factors are not static, yet do seem to have long term effects on policy, as with the resistance to social distancing and economic closure in both the US and UK where a return to high rates of infection have occurred at the end of the summer [155], while Germany and the Scandinavian countries have seen lower rates. This breaks down when one considers the massive increase in cases in Spain [156] while Italy shows a steady decline. While reopening for tourists seems to me a major factor, the response of government appears again to be a telling factor. This is made more clear when comparing US states, especially New York to the so-called red states, or the failure of California to be able to maintain social distancing and closure of businesses in a uniform fashion [157] (Figure 2). Cultural response to disease shows an independent and generally unrelated pattern. This is clear from comparing rates of infection from the Nordics and Germany to southern Europe. Data sources have changed in recent months, for example, in France home care infections and deaths in France were not initially included [158]. Reportage of infections and deaths seem to be affected by a number of factors and by reference to historical averages of deaths by season it appears the death rates are about 60% higher than normal [159]. Official rates on a per capita basis reported by the European Centre of Disease Prevention and Control [138] are as follows and show a distinct pattern (Table 1).

In examining the per capita data one finds that Sweden is not comparable with Denmark and Norway, but has a rate that is 3 to almost 10 times the latter countries. The UK and France have comparable rates but the geographic division fails in comparing Portugal and Greece to Spain and Italy. The connections of the viral strains from China and the transit of individuals [160] seem to interrelate with cultural and behavioral differences. One additional factor is the socio-economic aspect were we find immigrant groups like the Bame from Somalia in Norway with high rates (perhaps complicated by cultural factors) [161] in the USA and UK where minorities, especially African Americans are hard it by co-morbidities and poverty in housing status and jobs (many are in low paid delivery, stocking and clerking positions as well as health care and care for aged individuals both in institutions and home care [162].

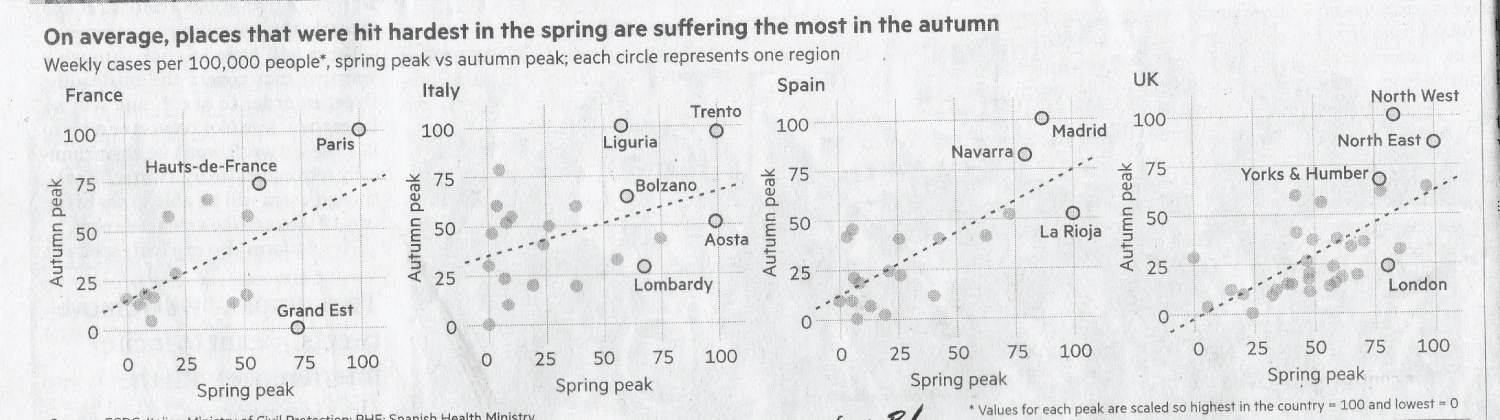

The use of new technologies and intensive tracing of contacts by government action is a different response and has been effective in South Korea, Germany, Israel and China [163,164]. The USA response and in the UK have been disorganized with the exception of some regions, as in California. Here political and cultural factors may be operating, as the most diverse parts of the country seem to be more proactive in testing and tracing contacts. Antibody tests in Southern California by USC researchers suggest infection rate could greatly exceed documented cases [165] which parallels a May UCSF study from the Mission and Bolinas [166]. This could bode well for the future as it might mean the mild or asymptomatic infections will not overload hospitals with severe cases, and the achievement of "herd immunity" is a practical goal or it could mean that the infection and cases are simply not yet producing severe disease in susceptible individuals. Yet evidence is accumulating that herd immunity may be difficult is not impossible to achieve with Covid-19. Dr. James Naismith, Director of the Rosalind Franklin Institute reminds us that there is no herd immunity for the common cold and Rupert Beale of the Francis Crick Institute called hopes for a Covid-19 herd immunity "wishful thinking" [167]. Though there is also evidence that infected individuals are producing a variety of antibodies, some less effective than others and more study of individual responses is necessary [168]. The prospect of endemic Covid-19 with yearly waves of concentrated deaths in people over 50 would have a substantial effect on the current demographic profile of developed countries. The idea of multiple waves of Covid-19 or persistence is supported by new evidence comparing cases from the spring break to autumn, data from the ECDC, Italian Ministry of Civil Protection and Spanish Health Ministry [167]. France, Italy, Spain and the UK all show significant case increases over the spring, Italy less so (Figure 3).

A comprehensive study of available ethnographic and historical evidence of human response to disease threat found similarities with of 5 major infectious diseases registering less than 25% agreement [31]. This would indicate perhaps that while these diseases are assumed to be relatively new to human experience as a whole, the evolutionary value of uniform behavioral response remains learned or passed down via myth, tales or other cultural means. A similar response to ancient, but recurrent catastrophic threat, was seen in the 2004 tsunami [169-171]. In fact, it seems that humans are devoid of any instinctual information concerning disease recognition. Understanding of jaundice where the skin and sclera of the eyes appears yellow due to the presence of bilirubin a bile pigment indicates a number of disease conditions (hepatitis, gallstones and tumors) should be a relatively easy signal to perceive. It is not clear that all humans have noticed this as a sign or disease or even if it only a recent recognition. Ideas of the evolution of the white sclera for disease recognition or social control of behavior are interesting but fail to provide specific evolutionary contexts, for example, the white sclera is not unique to humans but found also in macaques, see Figure 1 in Caldararo, 2009 [145]. We might expect human responses to be based on rational interpretation of signs and signals, but much of our information indicates that fear or perceived threats as defined culturally and as seen by individuals and processed into risks often are not rational processes and mob behavior, especially that described as mass psychogenic disease is an ill-defined process, especially in the current technological environment [2]. Evidence from antiquity is often clear on the irrational nature of responses [28].

One problem with such theories is the lack of a reference to human variation, for example, jaundice appears more readily as a difference where skill pigmentation is low and results from less melanin present. Human populations differ substantially in melanin deposition; some vary by season. One might argue that alcohol consumption, a major causal factor of the adult form, is too new a detriment to health to have produced a signal recognition of its presence. Jaundice does appear in the neonatal non-human Primate due to poor nutrition or starvation [172].

We should note, even in cases where adaptations to disease have developed into complex systems, in some as in health patterns in humans, novel disease overcomes them. A current case in the difference in "hygienic" bees which have what is considered an instinctual behavior to clean the hive of waste and foreign materials [173,174] do not seem to have faired any better when confronted with Colony Collapse Syndrome. Other cases of disease avoidance for the group are seen, for example, in ants where individuals exposed to the fungus Metahizium anisopliae (creates a pathogenic effect on hosts, Qui, 2019 [175]) leave the colony hours or days before death and die away from nest mates. Other examples of disease avoidance are given in Caldararo, 2012 [31].

Future of Megacities, Increased Population and Dense Living

This background to the current response to Covid-19 illustrates a global society where atomization and globally oriented manufacturing and distribution are creating fragility where we expect durability. Like a diversified portfolio of equities, bonds, etc. globalism was supposed to make our world more sustainable. Instead it has brought instability to the remotest parts of the globe. This fragility and, perhaps, failure of intent of investment, is mainly due to the concentration of responsibility and accountability in opaque financial institutions whose complexity of ownership makes tracing transactions near impossible. The recent case of Wirecard and the failure of accounting giant KPMG to validate reserves and third-party revenues are telling [176] as is the numerous breaches of rules by Barclays Bank [177,178]. Giving control of government funds for recovery, as in the cases of Blackrock [179] and Apollo Global Management [180] may only continue the dysfunctional culture of financialization and low investment in communities and healthcare that have resulted in the current institutional fragility.

In Singapore a substantial investment in housing seemed to make the city-state the envy of the world. The history of this achievement is presented in a simple story. "How Singapore Fixed its Housing Problem," we are told that the conditions of the war and how British colonialism had developed the area, led to a considerable housing deficit (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2cjPgNBNeLU). There was overcrowding, poverty and homelessness. The solution seemed to be found in an accidental fire that burned down the major slum and provided an opportunity to build low cost housing. While we may be skeptical over the origin of the fire and its "accidental" nature, the fact that the government used the freed up land (overriding concerns of ownership and claims to the land) for housing projects drawn from the needs of the majority of the population is remarkable. The fact that this trend has continued with more housing built to provide avenues for renters to own small apartments and for young families to move into larger units does seem to provide a model for rational development of housing based on need.

At the same time Singapore's economy has grown dramatically and many developments have been directed in design for middle incomes and luxury housing customers. Into this rosy picture we find a major criticism of Singapore's policy, population limitation. Many critics argue that Singapore's immigration policy is too limiting. Chih Hoong Sin in a 2002 [181] appraisal finds that the city state's ethnic quota policy, begun in 1989, was designed to produce a "balanced ethnic mix" but with 86% of the population living in government owned and run housing the outcome has been mixed itself.

However, the underside to this is noted by Charan Bal in a paper in 2017 [182], noting that one third of Singapore's workers (approximately 1 million) are from the Philippines, Bangladesh or Pakistan and are not allowed citizenship, permanent residence or official access to housing.

The pandemic has led to a concerted reexamination of city planning as reported in the Financial Times [25] in September, 2020. Sameh Wahba, World Bank global director for urban resilience and disaster risk management argues that designing the built environment to transform the problems of disease promoting density to livable density is the current goal. Eugene Gareache, managing director for Latin America and the Caribbean at the Global Resilient Cities Network notes that the pandemic has raised the focus on local level vulnerabilities in urban living. Remaking urban centers as healthy systems for living and working as well as reducing pollution and contamination from wastes has always been a problem of cities, but with today's technologies some policy makers believe sustainability if an achievable goal.

Conclusions: More Population or Investment in Infrastructure

The epidemic has ripped off the façade showing a vast hidden workforce of migrant labor living in squalid and dense conditions a perfect breeding ground for the virus [183]. Across the globe we see a similar picture, megacities built on old colonial foundations like Mumbai, Nairobi, Rio and Hong Kong reflect the massive population changes of the past 40 years as Western manufacturing has fled to low wage, low tax havens [184]. The hollowing out of the home countries' manufacturing capacity has been paralleled by a migration from the former colonies into the colonial capitals [185,186]. This was exacerbated by the counter move of Putin in supporting al-Assad in Syria to the West's support of Ukraine over NATO and Crimea. The massive refugee tidal wave smashed the political balance in most European countries and destabilized the EU. Now with the economic fallout over the Covid-19 pandemic this has reached a boiling point.

The more than 7 billion people in the world are living in denser conditions than ever before in human history. We are under assault by more pathogens and pathogens that are well adapted to both human ways of life and the human physiology. Transmission of pathogens either by sexual routes as in HIV, by attacking the developing fetus as in Zeka or in easily transmissible routes as in coughs, handshakes, surfaces of gathering places or transportation vehicles and packages will increase the speed of spread. We are at a crossroad about human future. Will we contain our population and attempt to produce sustainable conditions, approach climate change and modify our living structures (cities to rural hamlets?) or will we continue on as before? In his sweeping analysis of work, over the past 300,000 years, James Suzman [187] has demonstrated that the work of hunter gatherers had a rhythm and link to both individual satisfaction, social meaning and group achievement in ways lost since the period of mass society in the last 5,000 years. It is the missing frame for our lives that work, family, community and satisfaction are no longer united. The depression and loneliness that are the aroma of modernity are threats to the future of humanity.

While a vaccine for Covid-19 may appear and treatments for the infection become more effective, the fact remains that human society is creating conditions for more Covids and it is our response to disease as to living in dense conditions that may be the most dangerous future imaginable. Mass Psychogenic Disease is a disease of human presence, and that presence is only getting greater and more concentrated.

References

- Bartholomew RE, Wessley S (2002) The Protean nature of mass sociogenic illness: From possessed nuns to chemical and biological terrorism fears. Br J Psychiatry 180: 300-306.

- Bartholomew RE, Wessely S, Rubin GJ (2012) Mass psychogenic illness and the social network: Is it changing the pattern of outbreaks? JR Soc Med 105: 509-512.

- Frey BS, Savage DA, Torgler B (2010) Interaction of natural survival instincts and internalized social norms exploring the Titanic and Lusitania disasters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 4862-4865.

- Jones TF, Allen SC, Debbie HRN, et al. (2000) Mass psychogenic illness attributed to toxic exposure at a high school. New Eng J Med 342: 96-100.

- Lintott RA, Norman RA, Hoyle AS (2020) The impact of increased dispersal in response to disease control in patchy environments. J Theor Biol 323: 57-68.

- Chepko-Sade BD, Halpin ZT (1987) Mammalian dispersal patterns. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Haney C (2003) Mental health issues in long-term solitary and supermax confinement. Crime & Delinquency 49: 124-156.

- Smith PS (2006) The effects of solitary confinement on prison inmates: A brief history and review of the literature. Crime and Justice 34: 441-528.

- Maguire A (1978) Psychic possession among industrial workers. The Lancet 311: 376-378.

- Ong A (1988) The production of possession: Spirits and the multinational corporation in Malaysia. American Ethnologist 15: 28-42.

- Karl J (1953) The origin and goal of history. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Arnold T (1987) A study of history. Oxford University Press, London.

- Yoffee N, Cowgill GL (1988) The collapse of ancient states and civilizations. University of Arizona Press, Tuscon.

- Caldararo N (2015) Social behaviour and the superorganism: Implications for disease and stability in complex animal societies and colony collapse disorder in honeybees. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems 13: 82-98.

- Hertz N (2020) The lonely crowd. The Financial Times.

- Hertz N (2020) The lonely century: Coming together in a world that's pulling apart. Sceptre, London.

- Fone KC, Porkess MV (2008) Behavioural and neurochemical effects of post-weaning social isolation in rodents-relevance to developmental neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 32: 1087-1102.

- Harlow HF, Dodsworth RO, Harlow MK (1965) Total social isolation in monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 54: 90-97.

- Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, et al. (2016) Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart 102: 1009-1016.

- Kelly GA (1963) A theory of personality: The psychology of personal constructs. W.W. Norton and Company, New York.

- Laing RD (1965) The divided self. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth.

- Durkheim E (1915) The elementary forms of the religious life. The Free Press, New York.

- Jane J (1961) The death and life of great American cities. Random House, New York.

- Caldararo N (2019) An ethnography of the goodman building: The longest rent strike. Palgrave Studies in Urban Anthropology, Palgrave/Macmillan, New York.

- Wheatley J (2020) Pandemic forces rethink by city planners in emerging nations. The Financial Times.

- Cartwright FF, Michael DB (1972) Disease and history. Thomas Y Crowell, New York.

- McNeill WH (1976) Plagues and peoples. Doubleday, New York.

- Hope VM, Marsshall E (2000) Death and disease in the ancient city. Routledge, London.

- Valentina R, Murdoch JB (2020) Can ghost cities be revived? The Financial Times.

- Ma XC, Jiang WH, Wang F, et al. (2011) Social isolation-induced aggression potentiates anxiety and depression-like behavior in male mice subjected to unpredictable chronic mild stress. PlosOne.

- Caldararo N (2012) Some evolutionary aspects of disease avoidance. Scholar's Press, Saarbrucken.

- Harley D (1996) Explaining salem: Calvinist psychology and the diagnosis of possession. Amer Hist Rev 101: 307-331.

- Dobzhansky T (1973) Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. American Biology Teacher 35: 125-129.

- Paul E (1993) Evolution of infectious disease. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Azhar EI, David SCH, Ziad AM, et al. (2019) The Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS Infect Dis Clin North Am 33: 891-905.

- World Health Organization (2019) Plague.

- Stenseth NC, Bakyt BA, Mike B, et al. (2008) Plague: Past, present and future. PLoS Med 5.

- Demeure CE, Olivier D, Guillem MF, et al. (2019) Yersinia pestis and plague: An updated view on evolution, virulence determinants, immune subversion, vaccination, and diagnostics. Genes & Immunity 20: 357-370.

- Centers for Disease Control (2020) 1918 Pandemic influenza: Three waves.

- Chris W, Kluger J (2020) Alarming data show a third wave of COVID-19 is about to hit the U.S. Time Magazine.

- Caldararo N (1996) The HIV/AIDS epidemic: Its evolutionary implications for human ecology with special reference to the immune system. Sci Total Environ 191: 245-269.

- Doxiadis GGM, Nanine de G, Bontrop RE (2008) Impact of endogenous intronic retroviruses on major histocompatibility complex class II diversity and stability. Journal of Virology 82: 6667-6677.

- Woolhouse MEJ, Webster JP, Domingo E, et al. (2002) Biological and biomedical implications of the co-evolution of pathogens and their hosts. Nat Genet 32: 569-577.

- Villarreal LP (2011) Viral ancestors of antiviral systems. Viruses 3: 1933-1958.

- Lewis S, Gillian EW (1997) Origins of the V(D)J recombination system. Cell 88: 159-162.

- Murdock CC, Shirley L, Loren JC (2017) Immunity, host physiology, and behaviour in infected vectors. Curr Opin Insect Sci 20: 28-33.

- Waller J (2009) A forgotten plague: making sense of dancing mania. The Lancet 373: 624-625.

- Hagenback D, Lucius W (2013) Mystic chemist: The life of albert hoffman and his discovery of LSD. Synergetic Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

- Elias C (1966) Crowds and power. Viking Press, N.Y.

- Marshall M (2020) How Covid-19 can damage the brain.

- Omari IEl (2020) A new human being will emerge in the post-Covid-19 world. ORF Observer Research Foundation.

- Omori R, Mizumoto K, Chowell G (2020) Changes in testing rates could mask the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) growth rate. Int J Infect Dis 94: 116-118.

- Chakraborty I, Maity P (2020) Covid-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environmental and prevention. Science of the Total Environment 728.

- Milorad K, Jahic A (2020) How COVID-19 is changing the world: A statistical perspective. United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Reports.

- Jeffrey S (2006) Ecology and political upheaval. Scientific American.

- Taylor D, Robershaw P, Marchant RA (2000) Environmental change and political-economic upheaval in precolonial Western Uganda. The Holocene 4: 527-536.

- Weir E (2005) Mass sociogenic illness. CMAJ 172: 36.

- Aptheker H (1993) American Negro slave revolts. International Publishers, New York.

- Montagu A (1964) Man's most dangerous myth: The fallacy of race. Meridian Books, New York.

- Malinowski B, Phyllis MK (1945) The dynamics of culture change: An inquiry into race relations in Africa. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Reeves A, McKee M, Stuckler D (2014) Economic suicides in the great recession in Europe and North America. The British Journal of Psychiatry 205: 246-247.

- Langer A (1972) The mind of adolf hitler. Basic Books, Boston.

- Rohde D (2020) In deep: The FBI, the CIA and the truth about America's 'deep state'. WW Norton, New York.

- Case A, Deaton A (2020) Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Eisenstadt SN (1988) Beyond collapse. In: Norman Yoffee, George L Cowgill, The Collapse of Ancient States and Civilizations. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 236-243.

- Kuchler H (2020) Patient progress. The Financial Times.

- Boyer PS (1972) Salem-village witchcraft: A documentary record of local conflict in colonial New England, Northeastern University Press, Lebanon (New Hampshire).

- Burr GL (1914) Narratives of the witchcraft cases, 1648-1706. C. Scribner's Sons, New York.

- Hale J (1696) A modest enquiry into the nature of witchcraft. B. Green and J. Allen, Boston.

- Roach MK (2002) The salem witch trials: A day-to-day chronicle of a community under Siege. Cooper Square Press, New York.

- Timberg C, Chiu A (2020) As the coronavirus spreads, so does online racism targeting Asians, new research shows. The Washington Post.

- Joseph W (2020) Coronavirus protesters storm hospital in attempt to "rescue" patient. Daily News, New York.

- Carlos R (2020) Mexico urges end to harassment of health workers in pandemic. ABCNEWS and Associated Press.

- Mello MM, Greene JA, Sharfstein JM (2020) Attacks on public health officials during Covid-19. JAMA.

- Devi S (2020) Covid-19 exacerbates violence against health care workers. The Lancet 396: 658.

- Sonja AR, Ward JW, Goodman RA (2020) Protecting the editorial independence of the CDC from politics. JAMA.

- So LK, Lau AC, Yam LY, et al. (2003) Development of a standard treatment protocol for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet 361: 1615-1617.

- Prescott HC, Rice TW (2020) Corticosteroids in COVID-19 ARDS evidence and hope during the pandemic. JAMA.

- Sicore A (1986) H2-antagonists and the common cold. Annals of Internal Medicine 105: 803.

- Goldstein JA (1986) Cimetidine, ranitidine and Epstein-Barr virus infection. Ann Intern Med 105: 139.

- Wakefield D (1984) Cimetidine in recurrent genital herpies simplex infection. Ann Intern Med 101: 882.

- Rider TH, Zook CE, Boettcher TL, et al. (2011) Broad-spectrum antiviral therapeutics. Plos One.

- Yuan S, Hin C, Chan JFW, et al. (2019) SREBP-dependent lipidomic reprogramming as a broad-spectrum antiviral target. Nature Communications.

- Dobrindt K, Hoagland DA, Seah C, et al. (2020) Common genetic variation in humans impacts in vitro susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. BioRxiv.

- Benetti E, Tita R, Spiga O, et al. (2020) ACE2 gene variants may underlie interindividual variability and susceptibility to COVID-19 in the Italian population. European Journal of Human Genetics 28: 1602-1614.

- Dioscondi L, Carrisi C (2020) Covid-19 exposure risk for family members of healthcare workers: An observational study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 98: 287-289.

- Gandhi M, George WR (2020) Facial masking for Covid-19 - potential for 'variolation' as we wait for a vaccine. New Engl J Med 383: e101.

- Lawrence AK (2003) The sars epidemic: The scientists; Virus proves baffling, turning up in only 40% of a lab's test cases. New York Times.

- Hunyady B, Mezey E, Palkovits M (2000) Gastrointestinal immunology: Cell types in the lamina propria, a review. Acta Physiol Hung 87: 305-328.

- Diaz J, Vizuete ML, Taiffort E, et al. (1994) Localization of the histamine H2 receptor and gene transcripts in the rat stomach. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 198: 1195-2002.

- Fukushima Y, Ohmachi Y, Asano T, et al. (1999) Localization of the histamine H(2) receptor, a target for antiulcer drugs in gastric parietal cells. Digestion 60: 522-527.

- Mezey E, Palkovits M (1992) Localization of targets for anti-ulcer drugs in cells of the immune system. Science 258: 1662-1665.

- Biswas S, Benedict SH, Lynch SG, et al. (2012) Potential immunological consequences of pharmacological suppression of gastric acid production in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Med 10: 57.

- Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey S, et al. (2020) Famotidine against SARS-CovV2: A hope or hype? Mayo Clinic Proc 95: 1797-1809.

- Miki G, Sayre TJ, Allana S (2020) SARS-COV-2 and role of hydroxychloroquine.

- Derek L(2020) Famotidine, histamine and the coronavirus. Science Translational Medicine.

- Malone RW, Philiip T, Philip FS, et al. (2020) Covid-19, famotidine, histamine, mast cells, and mechanisms. Research Square.

- You S, Pan C, Yang X, et al. (2020) Mangement of critically ill patients with COVID-19 in ICU: Statement from front-line intensive care experts in Wuhan, China. Annals of Intensive Care 10: 73.

- Liu STH, Lin HM, Baine I, et al. (2020) Convalescent plasma treatment of severe Covid-19; A propensity score-matched control study. Nature Medicine 26: 1708-1713.

- Jennifer DVE, Cheng A, Krist A (2020) Regional strategies for academic health centers to support primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A plea from the front lines. JAMA Heath Forum.

- Allison TL, Bavari S (2019) Broad-spectrum coronavirus anti-viral drug discovery. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 14: 397-412.

- Knapp VJ (1989) Disease and its impact on modern European history. Studies in Health and Human Services, The Edwin Mullen Press, Lewiston, 381.

- Judith G (2020) What recovery from COVID-19 looks like. Sci Am.

- Jeong KY, Lee CN, Lee MS, et al. (2019) Recurrence rate of Herpes Zoster and its risk factors: A population based cohort study. J Korean Med Sci 34: e1.

- Souza INO, Barros-Aragao FGQ, Frost PS, et al. (2019) Late neurological consequences of Zika virus infection: Risk factors and pharmaceutical approaches. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 12: 60.

- Nature Editorial (2020) COVID research updates: The immune trait that could allow viral reinfection. Nature.

- Oliva A, Siccardi G, Migliarini A, et al. (2020) "Co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 with chlamydia or mycoplasma pneumonia: A case series and review of the literature. Infection 48: 871-877.

- Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, et al. (2020) Comorbidity and its impact on patients with Covid-19. SN Compr Clin Med 25: 1-8.

- McBride MC, Bergen KM (2015) Work spouses: Defining and understanding a 'new relationship'. Communication Studies 66: 487-508.

- Coulton GG (1930) The black death. Ernest Benn, London.

- Carlo C (1973) Christofano and the plague. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Carlo C (1976) Public health and the medical profession in the Renaissance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Carlo C (1977) Faith, reason and the plague in seventeenth century Tuscany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

- Carlo C (1981) Fighting the plague in seventeenth century Italy. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

- Dols MW (1977) The black death in the Middle East. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Mols RSJ (1977) Population in Europe 1500-1700, two centuries of demographic evolution. In: Carlo M Cipolla, The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Harvester Press, Hassocks, 15-82.

- Amy N (2019) The risks of social isolation. CE Corner. American Psychological Association 50: 32.

- Renato A (2020) Mental health in a pandemic state: The route from social isolation to loneliness. Psychiatric Times.

- Huesca ELdC, Aslanzadeh J, Feinn R, et al. (2018) Deposition of bacteria and bacterial spores by bathroom hot-air hand dryers. Applied Environmental Microbiology 84.

- Kim U, Bhullar N, Jackson D (2020) Life in the pandemic: Social isolation and mental health. J Clin Nurs 29: 2756-2757.

- Timothy M, Danese A, Wertz J, et al. (2015) Social isolation and mental health at primary and secondary school entry: A longitudinal cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54: 225-232.

- Centers for Disease Control (2020) Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups.

- Centers for Disease Control (2020) Contact tracing during coronavirus disease outbreak, South Korea.

- United States Census Bureau (2017) Average one-way commuting time by metropolitan areas.

- Gans HJ (1951) Park forest: Birth of a jewish community. Commentary 11: 330-339.

- Gans HJ (1962) The urban villagers: Group and class in the life of Italian-Americans. Free Press of Glencoe, New York.

- Fossum JC (1965) Rent withholding and the improvement of substandard housing. California Law Review 53: 304-336.

- Gans HJ (1967) Levittowners: Ways of life and politics in a new suburban community. Pantheon Books, New York.

- Niccolo C (n.d.) Fairfax, a small Marin County, California community.

- Oscar H (1973) The uprooted. (2nd edn), Atlantic Monthly Press, Boston.

- Charles D (1996) The wilding of America, how greed and violence are eroding our nation's character. St. Martin's Press, New York.

- Williams JC, Boushey H (2010) The three faces of work-family conflict. Center for American Progress.

- Payne S (2020) The hidden health costs of lockdown. The Financial Times.

- Dazio S, Briceno F, Michael Tarm Associated Press (2020) Crime drops around the world as COVID-19 keeps people inside. abcNews.

- Gina K (2011) Flu: The story of the great influenza pandemic of 1918 and the search for the virus that caused it. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

- Sun LH (2020) CDC director warns second wave of coronavirus is likely to be even more devastating. Washington Post.

- Arif H, Greb F, Sandstrom S, et al. (2020) COVID-19: Potential impact on the world's poorest people, a WFP analysis of the economic and food security implications of the pandemic. World Food Program.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2020) COVID-19 situation update for the EU/EEA and the UK, as of 5 October. Epidemiological Update.

- Anderson Christina, Henrik Pryser Libell (2020) Finland, 'Prepper nation of the Nordics,' isn't worried about masks. New York Times.

- Richard M (2020) Precise planning helps Finland contain Covid-19. The Financial Times.

- International Monetary Fund (2020) A crisis like no other, an uncertain recovery. World Economic Outlook Update.

- Gita G (2020) A long, uneven and uncertain ascent. IMF Blog.

- Chris G (2020) The week that austerity was officially buried. The Financial Times.

- Niccolo C (2007) Caching, money, magic, derivatives, mana and modern finance. J World Anth 3: 1-47.

- Niccolo C (2009) The tendency to make man an exception. Chapter 6. In: Emil Potocki, Juliues Krasinski, Primatology: Theories, methods and research, 113-128.

- Hall ET (1969) The hidden dimension. Anchor Books, New York.

- Jens A (1999) Are there Swedish patterns of communication? In: H Tamura, Cultural acceptance of CSCW in Japan & Norid Countries, 90-120.

- Peter C (1993) Foreign bodies: A guide to European Mannerisms. HarperCollins, New York.

- Phillips D (2020) Brazil congress demands Jair Bolsonaro release results of his COVID-19 tests. The Guardian.

- David P(2020) Low death toll in Africa raises hopes but amplifies calls for wider testing. The Financial Times.

- Munyaradzi M (2020) Covid-19 in Africa: Half a year later. The Lancet 20: P1127.

- Hiroshi K, Miyama T, Suzuki A, et al. (2020) Estimation of the asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19). Inter J Infect Diseases 94: 154-155.

- Jiji, Kyodo Press (2020) Extension of state of emergency mulled in Japan as COVID-19 continues to spread. Japan Times.

- Denyer S (2020) As infections ebb, Japan hopes it has cracked the covid code on coexisting with the virus. The Washington Post.

- Burgess S (2020) Rising numbers of positive covid-19 tests in the UK. BMJ 370.

- David J (2020) There is a simple reason Spain has been hit hard by the Coronavirus. The New York Times.

- Capradio (2020) California wavers on theme park opening rules amid pressure.

- Jennifer R (2020) Is comparing Covid-19 death rates across Europe helpful? The Guardian.

- John BM, Romei V, Giles C (2020) Death toll '60% higher than reported. The Financial Times.

- Rutherford GW (2020) 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Global Health Sciences.

- Clive C, Milne R (2020) Medics hunt for clues into high ethnic minorities death toll. The Financial Times.

- Yancy CW (2020) COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA.

- Yasheng H, Sun M, Sui Y (2020) How digital contact tracing slowed Covid-19 in East Asia. Harvard Business Review.

- Nic F, Espinoza J (2020) Tracking coronavirus: big data and the challenge to privacy. The Financial Times.

- Leigh H (2020) Early antibody testing suggests Covid-19 infections in L.A. County greatly exceed documented cases. USC News.

- Nicholas W (2020) COVID-19 testing in mission district, Bolinas to inform next steps in fight against disease. UCSF Patient Care.

- Bryan H, Pulice C, Cookson C, et al. (2020) Hotspots of resurgent Covid erode faith in herd immunity. The Financial Times.

- Kamran K (2020) Covid-19: Are neutralizing antibodies neutralizing enough? Transfusion.

- Malik JN, Frango CJ, Khan A, et al. (2019) Tsunami records of the last 8,000 years in the Andaman Island, India, from mega and large earthquakes: Insights on recurrence interval. Scientific Reports 9.

- Subir B (2005) Tsunami folklore 'saved islanders'. BBC Broadcast.

- Misra N (2005) Stone Age cultures survive tsunami waves. Associated Press.

- Naoya A, Fujie Y, Itoh T, et al. (2014) Glucose induces intestinal human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 to prevent neonatal hyuperbilirubinemia. Sci Rep 4: 6343.

- Rothenbuhler WC (1964) Behavioral genetics of nest cleaning in honey bees, IV, responses of F1 and backcross generations to disease-killed brood. American Zoologist 4: 111-123.

- Oldroyd BP (1996) Evaluation of Australian commercial honey bees for hygienic behavior, a critical character for tolerance to chalkbrood. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 36: 635-629.

- Qiu HL, Fox EGP, Qin CS, et al. (2019) Microcapsuled entomopathogenic fungus against fire ants, Solenopsis invicta. Biological Control 134: 141-149.

- Dan McC, Olaf S (2020) KPMG raises fresh issues on wirecard accounts. The Financial Times.

- Erin A (2014) Open secret: The global banking conspiracy that swindled investors out of billions. Penquin, New York.

- Croft J (2019) Top Barclays bankers 'created smokescreen to hide Qatari fees'. The Financial Times.

- Richard H, Wigglesworth R (2020) Blackrock tread precarious path to power. The Financial Times.

- Mark V, Indap S (2020) Navigating the crisis. The Financial Times.

- Sin CH (2002) The quest for a balanced ethnic mix: Singapore's ethnic quota policy examined. Urban Studies 39: 1347-1374.

- Bal C (2017) Myths and facts: Migrant workers in Singapore. New Naratif.