Cape of Good Hope? Meeting Place of Unwilling Migrants from Africa, Asia and Indigenous People

Abstract

The paper mainly deals with the large number of slaves from Asia and Africa imported to the Cape of Good Hope during the period 1658-1807. Apart from the (in-)human treatment of people from different continents, and the evils of slavery as a system, the new migrants eventually fused with the indigenous Khoikhoi, San and European population to create a new group of people that would eventually become known as the "Cape Coloured" community (In Afrikaans "kleurlinge" or "bruin mense"). At present this group consists of nearly 5 million people; 10% of the total South African population.

Recent research on the ethnic origin of the slave population of the Cape Colony in 1834 undertaken by Stellenbosch Museum and the Department of Economics at the University of Stellenbosch, sheds more light on the ethnic origins of the slave community. This contribution is based on the comprehensive lists of slave-ownership for the period 1816-1834 and also the list of names of slaves that appear on the compensation rolls drawn up in December 1834. (From 1834-1838 the former slaves became known as "apprentices").

For the period directly following the emancipation of slaves in 1834, the ex-slaves, Khoikhoi, San and a number of Europeans gradually intermarried to take on a new "coloured" identity. However, old terminology like Khoikhoi (and the pejorative term "Hottentot") often remained in use into the 20th century and featured in government records and correspondence until the 1930s.

Keywords

South Africa, Coloured people, Slavery, India, Mozambique, Madagascar, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Khoikhoi, San, Racial miscegenation, Integration

Background

During the period 1658 to 18071 large numbers of people from Asia and Africa arrived at the Cape of Good Hope as slaves. Over time they fused with the indigenous Khoikhoi, San and Europeans to create a new population group known as the "Cape Coloured"2 people, or "People of Colour".

Recent research on the ethnic origins of the "unfree" population of the Cape Colony in 1834 (based on more than 30 000 records transcribed from the records kept in the Government Archives in Cape Town and entered into a database by the author) sheds more light on the ethnic composition of the nearly 5 million people who have their ethnic and cultural roots in Africa, Asia and Europe. This diversity of cultures from Africa and Asia is reflected in the various religious affiliations of Cape people of colour who represent nearly 10% of the current South African population3.

The Setting

Until the settlement of the Dutch East India Company (DEIC or VOC) at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652, the sole inhabitants at the southern tip of Africa had been the Khoikhoi and San people: Herders and hunter-gatherers4. The vast herds of cattle and sheep made the Cape especially attractive to the DEIC to found a half-way, refreshment station on the way to the riches of India and the Spice Islands of Indonesia.

At the Cape, the Khoikhoi willingly traded their cattle and sheep to DEIC officials. However, sailors also needed vegetables and fruit and the DEIC encouraged soldiers and sailors to take up farming to supply visiting ships. In 1657 the first farms were allotted to Dutch and German5 agricultural "settlers". In 1688 the number of "European" farmers grew when French Huguenot Protestant refugees arrived at the Cape and settled in the larger Stellenbosch district to become successful wine producers6.

The budding new European farmers (free burghers, boere) soon complained that they needed farmhands to assist them in cultivating their small landholdings. The Khoikhoi flatly refused to do manual labour and the free burghers requested help in the form of slaves. The Khoikhoi could not be forced into labour as the charter of the DEIC, as dictated by the Dutch Government, expressly forbade the enslavement of indigenous people.

The DEIC took action in 1658. Portuguese slave ships on their way to Brazil were hijacked by Dutch ships in the mid-Atlantic and the slaves, hailing from Angola and Guinea, were taken to the Cape. This action led to a confrontation with the Dutch West India Company (DWIC) who claimed that the DEIC had violated their sphere of influence (west of the Cape and including the African-Atlantic seaboard). The DEIC mended its ways and in future all slave imports came from the Indian Ocean territories.

The Khoikhoi

For the first few years trade relations between the DEIC and Khoikhoi were excellent and the trading company respected the independence of the Khoikhoi chiefs. However, the Khoikhoi systematically lost their precious herds of cattle and sheep in exchange for "pleasure products" such as brandy and tobacco; also trinkets and cheap metal objects.

In 1700 the farmers received permission to obtain grazing licences for their cattle and sheep beyond the mountain ranges that surrounded the Cape settlement. What was originally permission granted to obtain grazing licenses soon turned into constant migrating "settlements" in search of new grazing land, and very important, the availability of water sources in the semi-arid regions to the north and north-east of the colony.

The white farmers, trekking into the interior, received little resistance from the Khoikhoi. The main reason for this lack of physical resistance was the fact that a smallpox epidemic which broke out in Cape Town in 1713, spread quickly into the interior where large numbers and settlements of Khoikhoi were virtually decimated. This was followed by further outbreaks of smallpox in 1755 and again in 1767.

The disease claimed not only the lives of the Khoikhoi - a very large number of slaves7 (and whites) died as well. However, the loss of lives could be compensated for by increasing slave imports and the recruitment of more workers in Europe to fill the staffing needs of the DEIC.

The Khoikhoi gradually moved away from the urban Cape and settled in a few areas where chiefs still nominally ruled over small groups. Even as late as 1807, a year after the end of the Dutch Batavian government rule at the Cape, the new British colonial government paid the Khoikhoi "Captains" Leopold Koopman and Thomas Smith in the Swellendam district an annual salary of £36-10 each8. But by this time the vast majority of cattle herding people at the Cape had lost their herds and acted as shepherds and cowherds in the service of the white farmers. By 1822 the custom of paying a salary to a Khoikhoi captain had already been done away with9. But the little "colony" of Khoikhoi in Swellendam did not just disappear; in 1825 the small settlement consisted of 460 adult males, 490 adult females, 331 boys and 413 girls10.

In the urban area of Cape Town in 1800, the names of only four Khoikhoi are recorded in the annual census of the town. All four were females and not purebred Khoikhoi as they were described as "Baster-Hottentot(s)"11. The near-absence of Khoikhoi people in Cape Town at a later stage, 1821, is confirmed by Rob Shell when only 2% of the inhabitants had been counted as Khoikhoi12. What was demographically true for Cape Town in 1800 was not true in the bordering Cape District with its wheat and wine farms where Khoikhoi labour also served alongside the imported and Cape-born slaves.

According to the government census of 1807 there were 1 432 "white"13 people living in the Cape district, 587 Khoikhoi and 4 293 slaves14. In Cape Town itself a handful of Khoikhoi were listed as residents. Whites engaged in agriculture in the district did employ Khoikhoi workers on a permanent basis. The widow of the prominent farmer Jacob van Reenen lived on the farm Ganzekraal not far from Cape Town where she employed five Khoikhoi men and 37 male slaves. Altogether 22 Khoikhoi and 51 slaves resided on the farm15.

The male-female imbalances on farms and towns: Where male slaves outnumbered women on a scale such as at Ganzekraal, (37 male slaves and only six women above the age of 14), led to male slaves often turning to Khoikhoi women as sexual partners. The children, all Bastard-Hottentots, were the result16.

On the farm of Willem van Niekerk, Zondagsfontein, there were 25 male slaves and only one Khoikhoi male registered two decades later. The total workforce consisted of 56 slaves and only five Khoikhoi individuals of all ages and genders17. This indicates a decline in Khoikhoi numbers on farms.

This phenomenon, miscegenation between slaves and Khoikhoi, took part on a large scale in the Cape district. On the farms in the interior, hundreds of kilometres from Cape Town, this occurred even more frequently as the bulk of the workers were Khoikhoi, not as in the Cape and Stellenbosch districts where the workforce consisted predominantly of slaves. The main occupation of the Khoikhoi, especially in the arid Karoo area, was that of herders, since agriculture was seldom practised. The 18th century has in the past indeed been described by (white) South African historians as "The Age of the Stock Farmer or Trek Boer"18.

Throughout the early DEIC period until 1795, the first British occupation from 1795-1803 and Batavian colonial era from 1803-1806, the number of Khoikhoi at the Cape is rather uncertain. This is illustrated by the British colonial official, W. Bird, who mentioned in 1822:

The number of free Hottentots not being correctly ascertained, was stated upon a rather vague estimate, in 1798, at 14,447. It has increased to 28,835; the number officially reported in 1821. This does not include the whole of the Hottentot population; but it does comprehend many of the bastard offspring of Hottentot mothers by European or Creole fathers19.

What Bird stated about racial intermingling between the Khoikhoi and European and Creole (Cape-born) slaves, also applied to relations between European men and slave girls:

So many years have passed away, since the Cape has been in the uninterrupted possession of the Dutch and the English, that from black, this class has graduated into brown or yellow, not much darker than a Southern European, and many have progressed to white20.

Counting the Khoikhoi in 2018

The counting of the Khoikhoi is new research topic among economic historians. Johan Fourie and Erik Green, respectively from Stellenbosch and Lund Universities, published their research on the Khoikhoi population in 2015. In 2016, La Croix from Hawaii, scrutinized their findings in an academic paper21. All these economic historians made use of early descriptions of the Khoikhoi by travellers and visitors as well as of official census and government records such as census and tax rolls.

One of the most important sources on Khoikhoi people was "rediscovered" by the Leiden historian, Robert Ross. During the 1990s he became aware of the appendices in an 1849 government report of the Cape Colony containing all the names of inhabitants of mission stations and other "Hottentot" institutions22. Included in these lists were also the names of slaves who had been fully emancipated in 1838. Not only were names listed but also occupation, ability to read and/or write and the economic situation of the heads of the household. Ross had the information transcribed at the University of the Western Cape and the information was entered on a computer database that contained 4,678 entries on households. The database was later refined at the University of South Africa. Based on the valuable information found in this database, at least two academic articles, based on the contents of the 1849 document, have since been published23.

Other important sources on Khoikhoi numbers are to be found in the annual census (Tax Rolls or Opgaafrollen) that have been kept since the introduction of free farmers in 1657. These lists contained the usual information of the head of the household and his/her family members. The number of slaves, listed by gender and age groups, were also recorded - together with the number of stock and agricultural produce. From the late 1790s, the statistics of the resident Khoikhoi within the household were added. Khoikhoi who lived independently, and who often moved around the countryside, were not recorded.

The missing Khoikhoi can be traced through mission station records from as early as 1737. However, it was only from 1792 onward that missionary work really became established in the Cape Colony and baptisms and marriages of Khoikhoi individuals in the country areas (joined by manumitted slaves) were recorded.

Mission registers and records contain a wealth of information in the process of "counting the Khoikhoi". But, as Bird mentioned before, the intermarriage between Khoikhoi and slaves, and also between white farmers, Khoikhoi and slaves, often mask the racial identity of the individuals recorded in registers and census statistics. For this reason, the government census of 1849, issued 11 years after the emancipation of slaves throughout the colony, is no true indicator of the number of Khoikhoi present.

Counting the Slaves

In contrast to the Khoikhoi, nearly all slaves who arrived at the Cape of Good Hope since 1658 had been documented and recorded as the property of someone; the DEIC, company officials or private individuals. Copies of digitized tax/census rolls dated from as early as 1670 through to 1800 are available at the Cape (Government) Archives in Cape Town. In these, the slaves of the burghers are listed by gender and by age. The names are not stated but the slave statistics are believed to be accurate. Individuals are listed by name in the numerous wills and estates in the Cape Archives24.

In 1977 Anna Böeseken, a former Cape Town archivist, published a list of all slave transactions occurring between 1658 and 170025. Her pioneering research was followed up by Leon Hattingh26 and again by Rob Shell who established a database recording slave transactions between 1716 and 1834 and listing 17,179 such transactions where the new owner is mentioned as well as the price paid for the slave27. In an addendum to his extensive study of slavery at the Cape28, Rob Shell also published an annual list of slave numbers at the Cape dating from 1652 through to 1834.

Digital records of 8,452 slaves emancipated in Stellenbosch district in the Western Cape have recently been published as an addendum to a recent study of slavery in this area. The names of all the slaves, their ages, occupations, places of origin, value in £-shillings-pence and the names and physical addresses of the owners are given29.

In 2017 the Department of Economic History at Stellenbosch launched a project (Laboratory for the Economic History of Africa's Past or LEAP). A subdivision of the "laboratory" is the Biography of an Uncharted People project that included inter alia the listing of all slaves who had been emancipated in 1834. The project was completed in June 2018 and includes information on 36 587 individual slaves freed30. At present a senior researcher with LEAP, Calumet Links, is carrying out intensive research on the Khoikhoi-element among the "missing people" project.

Origins of Slaves at the Cape of Good Hope

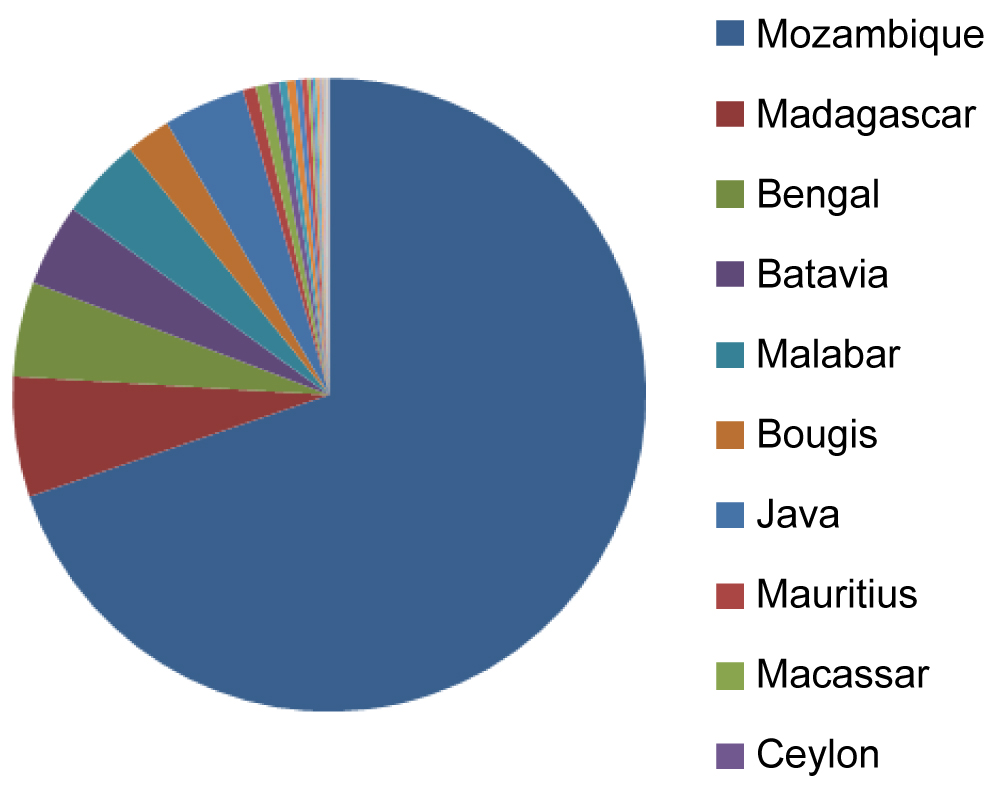

After 1658 the DEIC turned to importing slaves from India and Indonesia and the Celebes area. Slave ships were also dispatched to Madagascar and the African East Coast to buy and supply the DEIC establishment at the Cape with a sufficient number of slaves.

From the earliest transfers, sales and transactions where slaves at the Cape are mentioned, it appears that slaves from India (Bengal, Malabar and Coromandel) dominated from 1660 to 1670. This was followed by slave imports from Madagascar from 1673 onward when the Johanna Catharina was sent on a slaving expedition to the island. Numerous expeditions followed until 1784 when the Meermin brought its last consignment of slaves to the Cape settlement.

Records of the voyages and slave transactions are available in the Cape Archives. Lately a number of publications on Madagascar and the Cape connection, based on the original records, have been published31. During the DEIC period, slaves were imported from Mozambique in moderate numbers. With the Cape under British administration from 1795-1803, the largest number of Mozambican slaves32 ever were landed at Cape Town. When slaves were emancipated in 1834, Mozambican slaves outnumbered all other "imported" slaves by far: Mozambique-born slaves numbered 3,965, Madagascar-born totalled 349 and those from India 523 and Batavia 23933.

In the meantime Mozambique numbers increased through the landing of captured slaves ("prize negroes") in Cape Town by the British Navy that intercepted slave ships from the African East Coast heading for the Americas34.

Despite the fact that Mozambique slaves formed the largest "foreign" group among the imported slaves counted in 1834 (more than 10% of the total), the overall picture for the period 1658 to 1834 looks somewhat different. Using the original data of Rob Shell and adding new data, Prabha Rama came to the conclusion that in total Cape-born slaves formed 29.9% of the Cape slave population, Indians 25.6%, Indonesian Archipelago 16.83%, East Africa 14.11% and Madagascar 13.08%. The rest consisted of the relatively few West African slaves who arrived in 1658 and a fraction of a percentage was given as "other"35.

In this paper, based on the author's comprehensive database of more than 30,000 slaves registered by their owners for the period 1816-1834, as well as the list of individuals named to be freed in 1834, no attempt is made to come to definite conclusions about the ethnic composition of the Cape slave population36. There are too many varying factors to take into consideration, e.g. some Cape-born slaves, known as Van de Caab (from the Cape) could have had both male and female parents from Mozambique, or both parents from India. Or they may have been children of Malagasy fathers and Indian mothers born of Indian parents at the Cape37. To reach final conclusions, one has to rely on painstaking genealogical research - which will prove to be nearly impossible through a lack of reliable genealogical sources for Khoikhoi and slaves in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The following examples from comments in the list of slaves in the eastern Albany District to be emancipated in 1834, with very scant genealogical information, support this view38:

Silvie of the Cape, age 20, "a large healthy Mozambique".

Janetta of the Cape, "child of Constantia, nearly white, appears child from European father".

Christina of the Cape, born 1827, child of Sara, "looks like a Hottentot, father is a Hottentot".

Aletta of the Cape, born 8.8.1827, "appears Mozambique".

Doortje of the Cape, age 15, "appearance of being born to a European father".

Damon of the Cape, 54 years of age, "appearance of bastard European".

The following physical descriptions of slaves are found in the register for the Beaufort District39:

Romana of the Cape, age 29, "a Mozambique ... servant ........ Good looking".

Caatje of the Cape, age 17, "clever .... a Malabar".

Rosina of the Cape, age 7, appears "a little Hottentottish".

Spatie of the Cape, age 24, "a Mozambique".

Demas of the Cape, age 29, "a Mozambique".

September of the Cape, age 35, "a dark Malabar".

Amilie of Malabar, age 69, "a Mozambique".

Juliana of the Cape, age 34, "a healthy strong Mozambique".

David of Mozambique, age 49, "Malabar".

Christiaan of Rebecca of the Cape, age 16, "a Mozambique".

Jephta of the Cape, age 8, "a fine Mozambique".

Malatie of the Cape, age 15, "a healthy Mozambique".

Fritz of the Cape, age 33, "head servant", "Afrikaander, 6ft 3", in charge of oxen and trips to Cape Town".

Syda alias Annatje of the Cape, age 32, "Afrikaander" [and mother of Fritz's two children].

From the cases mentioned above, the stereotypes of slaves from different regions are clear. Slave women from Mozambique were viewed as physically very strong and were therefore nearly always employed as washerwomen in Cape society. The same applied to male Mozambique slaves but then again there were always exceptions: Among the occupations is a mention of the very specialized work of silversmith.

Slaves from Malabar were traditionally employed as more skilled workers although a large number also did the most menial work. This may indicate the case of that the male slave David of Mozambique stated above who might have been as skilful as a "Malabar".

Fritz and Syda of the Cape were both described as "Afrikaanders". Afrikaander was the term used to describe slaves with white fathers and slave mothers and indicated that they could easily pass for white. According to the historian Diko van Zyl, these half-white slaves were the highest valued category of slaves at the Cape40. Unfortunately, very few slave children from white-slave relations in the interior were baptized, especially as the 18th and 19th centuries progressed41.

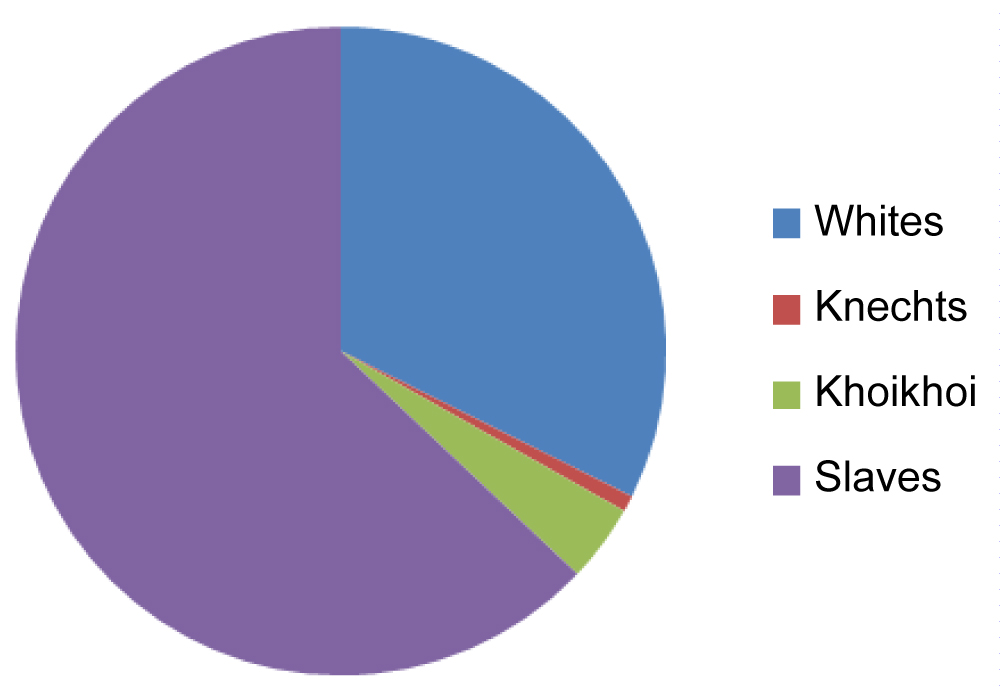

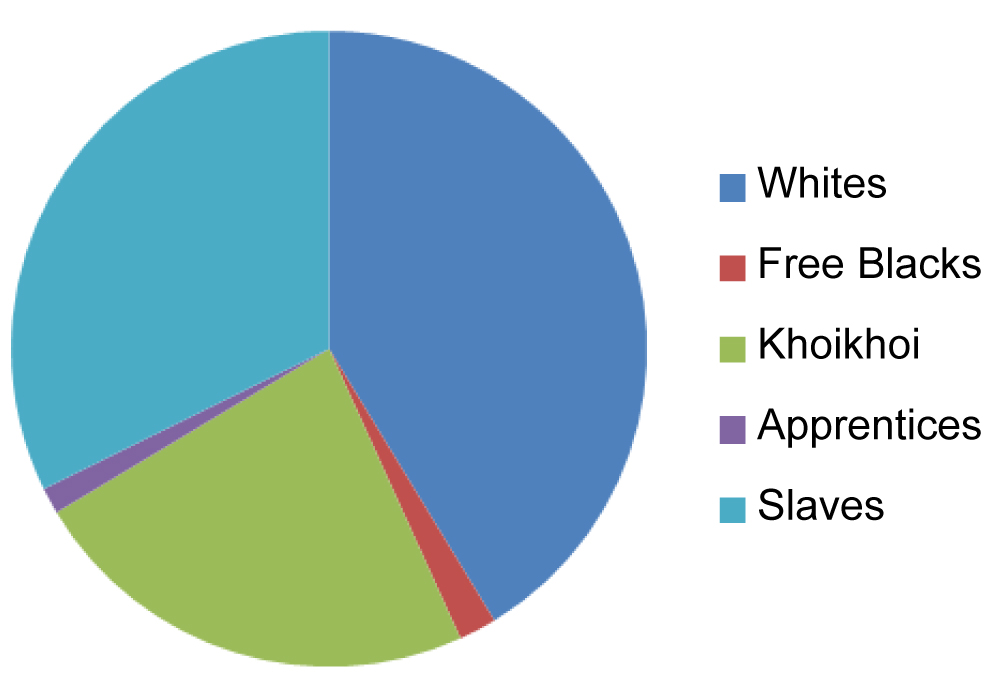

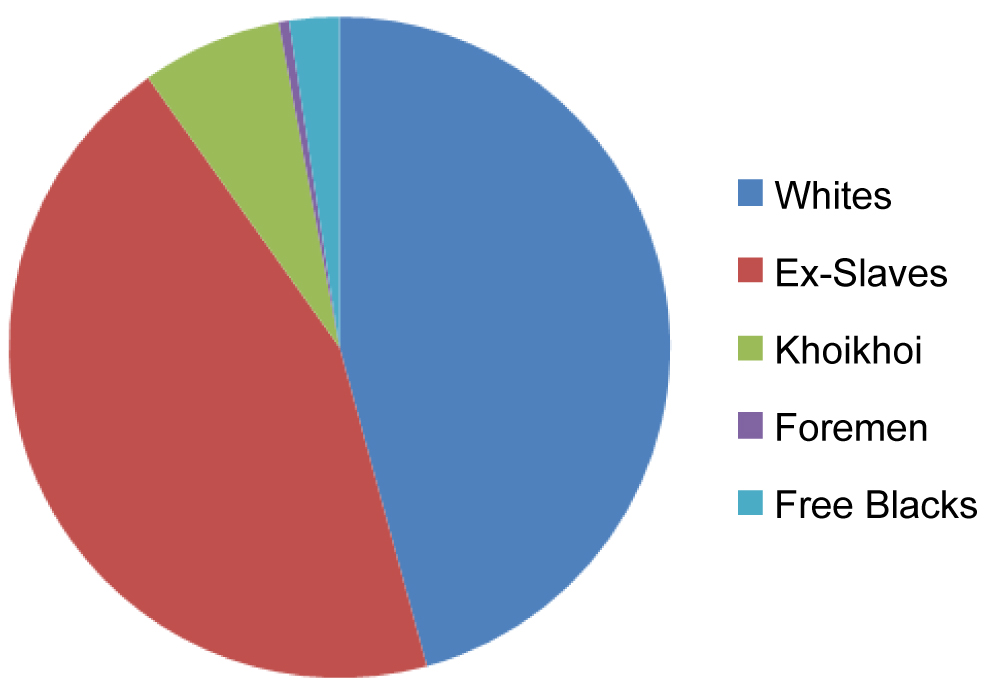

Counting people at the Cape

Cape colony population statistics, 1805-1838: The following data and statistics covering the various ethnic groups present at the Cape Colony have been compiled from various archival and contemporary printed sources and will provide a better understanding of the immigration, migration and the changing demography of the Cape population42-44 (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Development of a new identity after 1838

"(Cape) People of colour": On 1 December 1834 all slaves at the Cape were declared free. However, it was conditional as the former slaves had been "apprenticed" for four years to their former owners and could only legally leave the service of their former masters on 1 December 1838. As in the past, "masters" had to supply them with food, clothing, medicine and housing. In the 1835 tax rolls of the various districts, the headings were merely changed from "slaves" to "apprentices". There was virtually no change in the numbers in these tables.

The idea behind the apprenticeship was that the formers owners had to prepare them for freedom and the job market where they would in future have to fend for themselves. However, all responsibilities for the social advancement of the ex-slaves rested squarely on the former masters since the British colonial government did not make any attempt to provide vocational training, or any other training or guidance.

With the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807, no new slaves were imported to the Cape. The British also saw themselves as the policemen of the movement to stop slave ships reaching the Americas, especially ships sailing around the Cape of Good Hope. From 1808 onwards, a small naval force was kept at the Cape to approach ships and search for slaves - especially slaves from Mozambique and Madagascar. Between 1808 and 1815 more than 2,000 slaves, called "Prize Negroes", were landed at the Cape where they were "apprenticed" to "sponsors" for a period of up to 14 years. As late as 1842 no less than 1,300 "Prize Negroes" were sent from St Helena Island to the Cape to make up for the loss of the emancipated slaves who had left the farms where they worked, or to take the places of slaves who refused to work for their former masters in Cape Town45.

At the same time a new group of "apprentices" arrived at the Cape, just in time to ease the labour crisis that loomed ahead with the emancipation of slaves. The Children's Friend Society in London decided to send young male and female orphans to the colonies to "give them a better life" in the Cape Colony, Australia and Canada. At least 763 children from London arrived at the Cape where they mostly ended up on farms where they often shared the living quarters of the other apprentices "of darker complexion" in the Western Cape. This scheme was actively supported by Dr John Philip of the London Missionary Society in South Africa46.

As in the case of the freed slaves, virtually no vocational training under the traditional British apprenticeship-system followed; only in Cape Town a small number of the orphans learnt trades under the supervision of their "masters". Those who had been assigned to farmers became shepherds and ordinary manual labourers. In the Western Cape, half the male and female "London apprentices" eventually married freed slaves, adding to the wide variety of the complicated genetic pool of the ex-slave society47.

Improving the social (and economic) advancement of the ex-slaves was taken up by the various missionary societies in the Cape Colony - the London and Wesleyan Missionary Societies, the German Moravian, Rhenish and Berlin Societies as well as the South African Missionary Society. In the 1849 Parliamentary report, these missionary settlements had been described as "institutions" and covered the whole of the Cape Colony, including the Eastern Cape48.

Until 1838, the colonial government classified its inhabitants simply as white, slave and Khoikhoi with a special category "free blacks". "Free blacks" referred to slaves who had been manumitted by their owners before emancipation. They were mainly concentrated in Cape Town and consisted of slaves born at the Cape (Van de Caab) with the second largest group from Batavia (25). Bengal followed with 21 and Bugis with 12. Ceylon and Macassar were represented by 10 individuals from each region49.

The following graphics illustrate the effect which the emancipation of slaves in the Stellenbosch District had on the demography of the area. Of 8,500 slaves employed, mostly on farms, only 4,342 remained in the service of their former masters at the end of 1838. A thousand individuals are unaccounted for: they probably moved to neighbouring Cape Town where they lived in extremely overcrowded houses. Hengher stated in her thesis "where in low apartments, twelve feet square, as many as twenty human beings have been discovered lodging, feeding and sleeping"50,51 (Figure 4).

However, from 1838 onward, with all the "coloured" inhabitants now free, a new terminology had to be introduced to describe the recently emancipated slaves, the "Prize Negroes" the Khoikhoi and former slaves who had been manumitted before 1834 and who had been called "free blacks" from as early at the 17th century.

British Colonial Government and Racial Classification

The annual tax roll cum census for Stellenbosch of 1841 deviates from the traditional categorization of people into the following categories: Whites or Christians, Khoikhoi, apprentices and free blacks. Instead, from this year onwards, only two columns appeared on the census rolls that had to be filled out: Blanken and Kleurlingen (White and Coloured people)52. This new practice may well mark the beginning of the policy of racial classification followed in South Africa. African black people had up to this stage not been included in the record-keeping of the colony.

Ben Liebenberg wrote in 1953 that after emancipation in 1838, "the slaves and Khoikhoi merged to form the new Cape Coloured people"53. He did not, however, provide an explanation or source for this rather important statement on a new identity of people of colour. The above-mentioned census of 1841 for Stellenbosch may serve as part of the evidence which he did not provide. In the 1849 general census there were no "racial categories" other than "white" and "coloured". Referring to the number of Capetonians, it was mentioned that in the "liberal" Cape Town, no distinction was made between white and coloured and only one figure was given for the total number of inhabitants: 23,74954. Therefore, in a way, Cape Town was at least in theory, a model of a non-racial society in the mid-19th century.

Yet, despite the new official government racial terminology of simply white/coloured, old traditions and racial terms die hard. In official correspondence between the local authorities and the government offices in Cape Town, there are numerous references to "Hottentots" for the next few decades. In the 20th century the derogatory term "Hottentot" was still in use in day-to-day conversation and also recorded in biographical notes of a retired missionary of the Berlin Mission Society55.

In 1838 German Lutheran missionaries took up mission work in the South Western Cape among the ex-slaves and Khoikhoi. From the start they sent quarterly reports to Berlin where accounts of their work among the coloured people were published in Missionsberichte. For the first few years the pioneer missionary in this region referred to his flock as a mixture of Khoikhoi ("Hottentots") and "Basters" and only in 1855 did he refer to them as "Coloured" (Farbigen).

By 1860 the missionaries stated emphatically that the only place where Khoisan ("Hottentotten", "Saan" or "Buschmännern") were to be found, was in the Orange Free State. In the annual report of the same year (Jahresbericht), the society referred to the church members of their society in the Cape Colony who were collectively called "Hottentotten" although they stemmed from a genetic pool of "Japhetites, Hamites, Germanic people, Saan, Hottentotten and black people, the former the slaves of the colonists"56.

One of the missionaries in the Lang Kloof in the Western Cape, Friedrich Prietsch, mentioned in 1860 a certain "coloured" man, Abraham Paulse, who bought a farm for £2 000 and kept merino sheep and cattle and also owned forty horses. This Paulse held religious meetings for the "Hottentotten" in the surrounding area; without a doubt people with whom he shared a common genetic heritage. But Prietsch mentioned in the same report that some of members of his congregation lived in an adjacent "Hottentot" village where the dwellings were nothing but mud huts. It may be concluded that people were classified in ethnographic terms by their material culture: Coloured people lived in houses; "Hottentots" lived in huts57.

It was only at the beginning of the 20th century that the misnomer of "Hottentot", to describe people of partly Khoikhoi stock, fell into disuse with the German missionaries and were replaced by the terms Brown People (Braunen) or Cape People (Kapenaars)58; two terms that are still used in Cape society today and are not racially offensive to the vast majority of people of colour. The use of the new terminology "Brown" by the missionaries preceded the title of a book that was written by a coloured author on the problem of racial admixture two decades later59.

Coloured Viewpoint

The late Richard van der Ross, a respected Coloured intellectual, academic and later rector of the "Coloured" University of the Western Cape (UWC), was a regular columnist under the heading Coloured Viewpoint for the Cape Times. The column ran from 1958 to 1965. In his articles he highlighted the grievances and the wrongs that the coloured people had suffered under the apartheid government since 1948. But he also wrote about the higher aspirations of "his" people; he never for one moment doubted his "coloured identity". Doubts about "colouredness" as cultural or ethnic markers among Coloured people only came to the fore in the political turmoil of the 1970s and 1980s in South Africa.

In an article, "An Open Letter to Mr. Harold Macmillan" on 28th January 1960, Van der Ross described the racial situation of Cape Town very briefly but accurately. He made no mention of a particular race group but suggested that in Cape Town there was a significant non-racial (Coloured) group to be found:

Dear Mr. Macmillan, - Welcome to South Africa and particularly to Cape Town, This is a unique city. Nowhere else in South Africa will you find a community so mixed racially, so schooled in methods of living together60.

Yet there is another view of the term "Coloured", this time by a former "Coloured" political activist during the 1980s and 1990s:

Preliminary Remarks

The South African community is beset by racism and racist terms, therefore it is of the utmost importance that the following terms are explained, for they will appear throughout this paper.

Khoikhoi: This is the name for the pastoralists, whom the travellers and Europeans met when they made contact on the South Western coast of the Cape. It means men of men, people of pure race and it is the one name for the different tribes.

San: This is the name of the hunter-gatherers. They share linguistic and other cultural features with the Khoikhoi and at one stage were one group of people with them, the Khoisan

The terms Hottentot and Boesman/Bushmen are derogatory, racist terms denoting Khoikhoi and San respectively, and have been used in this paper only when quoting from the works of other people.

Coloured: This is a racist term to describe a certain sector of the S.A. community, who are not white. The Coloureds consist of the descendants of the Khoikhoi, slaves and European and African miscegenation61.

Another View from a Young Kapenaar

Nathan Trantaal, a born and bred "Kapenaar" and both poet and author, published a book in 2018 under the title Wit issie 'n colour nie. ("White is not a colour"). He then gives a definition: "White is not a colour, it is a religion handed down from birth"62. Religion, a very essential part of culture, perpetuates the attitudes of South Africans who consider themselves "white" and belonging to "white culture" - in its broadest sense.

Coloured to Black to Khoisan to Brown?

At the time when Van der Ross was the Rector of UWC, one of the former UWC students, Willa Boezak, stated that during the 1980s he and other students rejected their "coloured" identity and became culturally and politically "black". However, during the 1990s, he re-"discovered" his Khoisan identity and became a leading figure in the South African Khoisan cultural revival movement63.

The founding of the Khoisan cultural identity was preceded by an organization that started in 1996 as the 1 December Movement. The driving force of the movement was to acknowledge the important part played by slaves in the formation of the Coloured people, especially in Cape Town and the Western Cape. One of the aims was to have 1 December, the day that slaves had been emancipated at the Cape, declared a national holiday in the new democratic South Africa. However, the movement did not gain popular support among coloured people and under Bennie Alexander, a former Secretary General of the PAC, who took on the new name of the "Khoisan X" in 1994, tended to accentuate the Khoisan heritage instead64.

In 2001 there was a revival of Khoisan identity when 440 delegates from 36 Khoisan communities gathered at a "National Khoisan Consultative Conference" at Oudtshoorn in the Little Karoo. A significant outcome of the deliberations at this meeting was that they agreed that some of the groupings within "coloured" society could not be, or become, Khoisan: the Muslims and Cape Malays65.

The Khoisan movement is still very vocal in stating their lost identity (and land) and from time to time these issues feature in the South African press and media. This may be connected to the current land debate and the intended new legislation of the ruling political party to expropriate land and property without financial compensation. The Khoikhoi and San were, after all, the "first people" who inhabited the largest geographical area of present South Africa. However, it seems that there are so many factions and opposing leaders within the Khoisan community that they cannot agree on unity to present their case. The latest in a series of actions involve "King" Calvin Khoebaha Cornelius lll of the new "Sovereign State of Good Hope". On Monday 16 July 2018, the "king" lowered the national flag at Parliament House in Cape Town and had his own flag hoisted. At the same time he informed President Cyril Ramaphosa that he should leave the premises66!

This radical action by the self-proclaimed king (2018) was condemned by Cecil le Fleur, chair of the National Khoisan Council as well as by other recognized Khoisan leaders who have been acknowledged by government. Le Fleur67, a Griqua leader, does not represent the "coloured community" in general. During the apartheid regime, the small Griqua community was recognized by the apartheid government as a separate entity within the larger coloured or "non-white" community68. They were also recognised by the new democratic government who gave them title to the farm Ratelgat in the Western Cape to develop a Griqua cultural centre.

A well-known veteran "coloured" politician, Peter Marais, recently founded the Bruin Bemagtigingsbeweging, or BBB (Brown Empowerment Movement). At the same time he also acted as spokesman for the Griqua Royal House in the public hearings on the redistribution of land69. From this it can be deducted that "Brown" does not exclude those of Griqua, Khoikhoi or San origins.

"Brown" or "coloured" identity today, of course, also includes slave ancestry. Richard van der Ross, a Capetonian by birth, stressed the slave origins of at least one very prominent historic coloured leader from this geographical region, Abdullah Abdurahman. Van der Ross, partly of slave descent himself, also privately and publicly stated later in his life that he had no problem with the terms "kleurling" (coloured) and "bruin" (brown)70.

The (perhaps vast) majority of people of colour, at least in Cape Town and the Western Cape region, where slaves and their descendants have, since the days of slavery, been the single largest population group, accept that they are descendants of slaves, whites and Khoisan. They do not object to calling themselves, "brown", or being called that by other groups71.

A View from East Berlin, 1954: Who are these Coloured People72?

The Director of the Berlin Missionary Society at the time, Gerhard Brennecke, visited the South African mission stations between 1950 and 1952 and gave a very accurate description of the coloured (Farbigen) people.

He accurately stated that within this group are found individuals who represent the whole spectrum from white to black. He explained the assimilation that had taken place as a result of slaves marrying - or living with - Khoikhoi women; also intermarriage between Whites (Dutch, German, French, Jewish, Portuguese - and especially English) and "Hottentots". To a lesser degree, San genes had also been added in this process. Brennecke particularly stressed the role of slaves from East Africa and Madagascar and those from Malaysia and the racial mixture between all the groups already present at the Cape73. His definition of coloured people, formulated around 1953, would have been complete if he had also added the large number of Asian slaves from India, Sri Lanka and Indonesia.

What Brennecke did not know was that the Asian slaves imported from India and Sri Lanka by the Dutch DEIC were in all probability not always "racially pure". An investigation by Professor Franken into the language spoken by Indian and Sri Lankan slaves sentenced at the Cape Court of Justice indicated that a large number could speak and understand Portuguese but not Dutch74. From Boxer's research it may deduced that racial miscegenation between slaves in India and Sri Lanka and the Portuguese soldiers and sailors had taken place on a large scale75; as was the case at the Cape of Good Hope. It is quite possible that slaves from India imported to the Cape in the 18th century, where the Indian coastal areas had been controlled by the Dutch for almost a century, were of mixed Indo-European origin.

The Director of the Missionary Society might also have mentioned that the Farbigen of Cape Town and immediate districts differed in outward appearance from congregants of his Society from up-country; in the Cape Peninsula those of Khoisan origin formed a minority among the "coloured" population76.

Conclusion

The ethnic make-up of the present "Cape Coloured" population is extremely diverse with genetic markers of slaves from Africa and Asia which is so thoroughly intertwined with people of Khoisan and European origin that probably no living individual can today claim to be a descendant of one exclusive ethnic group77. The same applies to "white" South Africans, especially Afrikaners, a group that evolved over a period approaching four centuries. Afrikaners, who traditionally have had an obsession with studying their family trees and genealogy, largely ignored their partly slave, partly Khoikhoi ancestry until a few decades ago. Dramatic political changes since 1990 have changed this attitude and individual Afrikaners now take pride in their slave and Khoikhoi roots to prove that they are also truly indigenous and not only the descendants of European "settlers".

Individuals of colour from Namaqualand and isolated areas bordering the Kalahari Desert in the Northern Cape Province may consider themselves to be of pure Khoikhoi or San origin - at least from outward appearance. This applies especially to those who can still speak their original Khoikhoi or San languages and who advocate a return to their traditional culture as well as their tribal areas. This may give them the added advantage of political and economic spin-offs.

There is, however, also a new movement among "coloured" people in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces to re-establish the old Khoikhoi chieftain-system78 where a few individuals may gain the material benefits awarded to the traditional leaders (chiefs) of the pre-colonial black African society in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. This system became part and parcel of the old British colonial tradition and was later manipulated to serve the apartheid system to its advantage. Traditional Xhosa and Zulu chiefs still enjoy material benefits and wield political power.

By reverting to Khoikhoi and Khoisan identity, members of the "coloured" community deny their very important slave roots. When the "National Khoisan Consultative Conference" decided that all groupings within the "coloured" society could become members of the wider Khoisan movement, the Muslims and Cape Malays had been excluded79. By implication the descendants of slaves from Africa could become "Khoisan" but not all of those who hailed from India, Sri Lanka or Indonesia, who profess the Muslim faith.

Because of the inconsistency within "coloured" society as mentioned above, and as seen by the emerging and popular Khoisan movement, it may perhaps be wise to revert to "brown" as a new, neutral term to describe the old and dated classification of Coloured People: descendants from slaves, Khoisan and Europeans.

Taking a leaf from Trantaal on "white" identity: "White is not a colour, it is a religion handed down from birth80", the author would like to defer to Trantaal and respectfully suggest the following definition: "Brown" is not a colour, it is a (non-racial) cultural group unique to South Africa81".

1A few DEIC officials at the Cape privately owned slaves before 1658 but the need to import slaves to ease the labour shortage at the new settlement only started off in 1658. See James Armstrong: "The Slaves, 1652-1795" in Richard Elphick and Hermann Giliomee, The Shaping of South African Society, 1652-1820, pp. 75-115, Cape Town, 1979. In 1806 the importation of slaves into British colonies, including the Cape of Good Hope, was forbidden by a British Act of Parliament in this year. Slaves "liberated" by British war ships found their way to Cape Town where they were known as "prize negroes" who were indentured to members of the local Cape population. See: Christopher Saunders, "Between slavery and freedom: The importation of prize negroes to the Cape in the aftermath of emancipation", Kronos, 9, 1984.2The term "Coloured" is frowned upon by many people of mixed racial descent as it is associated with the South African (Apartheid) Government Racial Classification Act, no. 30 of 1950. Currently the Afrikaans term "bruin mense" (brown people) is more acceptable to people who are of mixed-race or bi-racial descent. Two studies referring to "Cape Coloured People", became classics; J.S. Marais, The Cape Coloured People, Johannesburg, 1937, and A.L. Venter, Coloured: A profile of two million South Africans, Cape Town, 1974.

3According to the 2011 government census the South African population was calculated at 51.7 million with "Coloured People" and "Whites" totalling 4,615,401 and 4,586,938 with 1,286,930 citizens classified as Indian/Asian. See https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/people-culture/people/south-africas-population (accessed 25/7/2018).

4Since the (traditional) terms Hottentot and Bushmen are now considered "colonial" and pejorative, the terms Khoikhoi and San will be used to denote these two groups. However, it must be pointed out that living "Bushmen" do not necessarily view it this way as the Khoikhoi word San actually means "cattle thieves".

5Large numbers of Germans signed up as soldiers with the DEIC in Amsterdam to escape the poverty and despair of their country after the Thirty Years War that ended in 1648. There were nearly as many Germans as Dutch sailors and soldiers serving with the DEIC at the Cape of Good Hope. See J.A. Heese: Die herkoms van die Afrikaner, 1657-1867, Cape Town, 1971. According to his calculations, the white Afrikaner population stems mainly from Dutch immigrants (36.8%), German (35%), French Huguenot (14.6%) and a "non European" group - consisting of mostly imported slaves.

6See the article of Johan Fourie and Dieter von Fintel: "'n Ongelyke Oes: Die Franse Hugenote en die vroee Kaapse wynbedryf", Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers, 29/10.

7See the graphics in: R. C-H Shell, Children of Bondage. A social History of Slave Society at the Cape of Good Hope, 1652-1838, Johannesburg, 1997, p. 78. Also: H. Heese, "Mortaliteit onder VOC-slawe", Kronos, 11, 1986, Bellville, pp. 7-14.

8G.M.Theal (ed.), Records of the Cape Colony, Volume 35, London, 1897, p. 62.

9W. Bird, State of the Cape of Good Hope in 1822, London, 1823, p. 335.

10Cape Archives, J 350, Census Roll of Khoikhoi, Swellendam, 1825. At least a third of the names listed are typical slave names; the occurrence of "European" surnames indicates racial miscegenation within this community.

11Cape Archives, J 443, Census Roll Cape Town, 1800. The term Baster (Bastard) Hottentot was used for a child born from a slave male and Khoikhoi female. As the offspring of a free mother, the child was also free at birth.

12R. C-H. Shell, Children of Bondage. A social History of Slave Society at the Cape of Good Hope, 1652-1838, Johannesburg, 1997, p. 143.

13In early Cape settler society, "White" people had not always been lily white: It is estimated that about 7% of the (mostly) female ancestors (white) Afrikaners were of slave descent. See J.A. Heese, Die herkoms van die Afrikaner, Cape Town, 1971, p. 56.

14Cape Archives, J 41, Census Roll Cape Town, 1800. See also E. Rosenthal (ed.), Cape Directory 1800, Cape Town, 1969.

15Cape Archives, J 54, Census Roll 1823.

16The marriage of the Danish explorer Pieter Meerhof to the Khoikhoi interpreter Krotoa alias Eva, in 1664, was a once off for the 17th century. The children from the marriage were all assimilated into "white" society. For more information on racial intermarriage between the various ethnic and social groups during the DEIC period, and the process by which ex-slave women were accepted in mainstream society, see H.F. Heese, Groep sonder Grense, Bellville, 1984. Delia Robertson translated the book into English under the title Cape Melting Pot. The book can be downloaded at http://www.e-family.co.za/ffy/RemarkableWriting/CapeMeltingPot-FFY.pdf (accessed 25/7/2018).

17Cape Archives, J 54, Census Roll 1823.

18D.W. Kruger (ed.), Geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika, Cape Town, 1964, p. 85.

19W. Bird, State of the Cape of Good Hope in 1822, London, 1823, p. 354.

20W. Bird, State of the Cape of Good Hope in 1822, London, 1823, p. 373.

21J. Fourie and E. Green, "Missing People: Accounting for the Productivity of Indigenous Populations in Cape Colonial History," Journal of African History 56 (2), 2015; S. La Croix, "The Decline of the Khoikhoi Population, 1652-1780: A Review and a New Estimate", Working Paper, no. 16-22, 2016, University of Hawaii.

22Cape of Good Hope. Master and Servant. Documents on the working of the Order of Council of the 21st July, 1846, Cape Town, 1849. The reason for this census was the insistence by white farmers that former slaves/workers were living in idleness on the mission stations after the emancipation of slaves a few years earlier. The farmers wanted to employ the "idle" men as farm labourers after they lost the service of the slaves who often left the farms for mission stations and larger towns and also Cape Town.

23R. Ross and R. Viljoen, "The 1849 Census of Missions in the Cape Colony", South African Historical Journal, 61, 2, 2009, pp. 389-406. Also J. Fourie, R. Ross and R. Viljoen, "Literacy at South African Mission Stations", Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers: 06/13, March 2013. In both studies, the authors wrongly classified the Zoar mission station as a South African Missionary Society station although it was in fact operated by the German Berlin Missionary station.

24The tax rolls can be found in the J-series and wills in the MOOC-series document collections. The wills for the Stellenbosch District have also been digitized and available on CD: A. Krzesinkski-De Widt, Die Boedelinventarisse van Erflaters in die Distrik Stellenbosch, 1679-1806, Stellenbosch Museum, 2002.

25A. Boeseken, Slaves and Free Blacks at the Cape, 1658-1700, Cape Town, 1977.

26J.L. Hattingh: "Slawevrystellings aan die Kaap, 1700-1720", Kronos, 4, 1981; J.L. Hattingh: "A.J. Boeseken se addendum van Kaapse slawe-verkooptransaksies; foute en regstellings", Kronos, 9, 1984.

27R.C-H. Shell, Changing Hands, Excel database, Cape Town, 2013.

28R. C-H Shell, Children of Bondage. A social History of Slave Society at the Cape of Good Hope, 1652-1838, Johannesburg, 1997, pp. 445-448.

29H.F. Heese, Amsterdam tot Zeeland. Slawestand tot Middestand?, 'n Stellenbosse slawegeskiedenis, 1679-1834, Stellenbosch, 2016. The lists of compensation claims for slaves were consulted physically in the Cape Archives. However, copies of these original lists are now available on the LDS FamilySearch website. See e.g. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GBFG-ZD4?i=4&wc=Q8GM-RDT%3A231840001%2C231840002&cc=1935348 (accessed 25/7/2018).

30See the LEAP website: https://leapstellenbosch.org.za/#group-2 (accessed 25.7.2018).

31P. Westra and J.C. Armstrong, Slave Trade with Madagascar, Cape Town, 2006; D. Sleigh and P. Westra, Die aanslag op die slaweskip Meermin, 1766, Cape Town, 2012.

32Slaves born in Malawi and surrounding areas, and brought to Zanzibar to be sold at the slave market, were all described as "Mozambique" slaves. A number of Malawian Chewa-speaking "prize negroes" reached the Cape. E-mail communication from Zambian-born professor Martin Pauw to the author, 16.9.2018; See also Nathan Nunn: "The Long-Term Effects of Africa's Slave Trades", Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(1), 2008, Data Appendix, 2007, p. 26.

33Slave database assembled by the author for the Stellenbosch Museum and the Biography of an Uncharted People project of LEAP, Department of Economics, University of Stellenbosch.

34C. Saunders, "Between slavery and freedom; the importation of prize negroes to the Cape in the aftermath of emancipation", Kronos, 9, 1984.

35P. Rama, "Places of Origin of the Slaves at the Cape of Good Hope, 1658-1834", Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa, 72, no 1, June 2018, pp. 21-36. Rama included the Sri Lanka (Ceylon) slaves in the "Indian" group. See also the findings on the origins of slaves in A. Bank, The decline of urban slavery at the Cape, 1806-1834, Cape Town, 1991, p. 232.

36For more information on the comprehensive slave database established by the author, and on the findings this paper is based on, see the abstract of this paper.

37See the case of the son of the emancipated slave Sambouw of Madagascar who had married Rachel of the Cape. Their son married a Dutch woman and the children had all been accepted in "white" society. See H.F. Heese, Groep sonder Grense, Bellville, 1984, p. 53.

38Cape Archives, SO 20/5, Appraisement of Slaves for the District of Albany, 1834-1835.

39Cape Archives, SO 20/6, Appraisement of Slaves for the District of Beaufort, 1834-1835.

40D.J. van Zyl, "Die slaaf in die ekonomiese lewe van die westelike distrikte van die Kaapkolonie, 1795-1834", Suid-Afrikaanse Historiese Joernaal, 10, 1978, p. 20.

41In Cape Town, all slaves born in the slave lodge had been baptized. Usually the white father was indicated as an "unknown Christian" but on occasion the name was mentioned. Because of meticulous recording it is possible to reconstruct genealogies of these slaves. See H.F. Heese, "Slawegesinne in die Kaap, 1665-1795", Kronos, 4, 1981.

42Cape Archives, Cape Town, Tax Roll, J 39, 1805. The number of individuals mentioned in the tax roll of 1805 differs considerably from that given by Andrew Bank for 1806, namely 17,446. A. Bank, The decline of urban slavery at the Cape, 1806-1834, Cape Town, 1991, p. 231. He probably included the number of inhabitants for the Cape District as well. What is significant about Bank's research is that the slave population of Cape Town steadily declined from 9,367 in 1806 to 6,222 in 1827, p. 236.

43W. Bird, State of the Cape of Good Hope in 1822, London, 1823, p. 107.

44Based on an (incomplete) list of emancipated slaves of foreign origin found in compensation lists; Cape Archives, SO 20/5-20/16, 1834-1835.

45C. Saunders, "Between slavery and freedom: The importation of prize negroes to the Cape in the aftermath of emancipation", Kronos, 9, 1984, pp. 36-39.

46M. van Bart, Kaap van Slawe, Cape Town, 2012, pp. 143-147.

47H.F. Heese, Amsterdam tot Zeeland. Slawestand tot Middestand?, 'n Stellenbosse slawegeskiedenis, 1679-1834, Stellenbosch, 2016, p. 79. For a list of orphans that came to the Cape, see https://www.geni.com/projects/The-Children-s-Friend-Society-Master-South-African-List/14276 (accessed 1.9.2018).

48Cape of Good Hope. Master and Servant. Documents on the working of the Order of Council of the 21st July, 1846, Cape Town, 1849.

49Cape Archives, Tax Roll, Cape Town, 1800, J 38.

50E. Hengher, "Emancipation and After, A study of Cape Slavery and the issues arising from it", Unpublished MA-thesis, University of Cape Town, 1953, p. 79. Hengher quoted from the Commercial Advertiser of the time.

51Cape Archives, Tax Roll, Stellenbosch, 1838, J 308.

52Cape Archives, Tax Roll, Stellenbosch, 1841, J 312. See also the following tax rolls of 1843 (J 314) and 1844 (J 315) that follow the new "racial classification".

53B.J. Liebenberg, "Die vrystelling van die slawe in die Kaapkolonie en die implikasies daarvan", Unpublished MA-these, University of the Orange Frees State, 1953, p. 102.

54British Parliamentary Papers, Colonies Africa, 23, Irish University Press Series, n.d., p. 551.

55C.H. de Wit: "Die Berlynse Sendinggenootskap in die Wes-Kaap, 1838-1961, met spesiale verwysing na die sosio-ekonomiese en politieke omstandighede van sy lidmate." Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Stellenbosch, 2006, Electronic version at http://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/50598, downloaded on 13.9.2017, p. 237.

56H.F. Heese, "Khoisan in Kannaland: Observations by the German Lutheran Missionaries, 1838 to 1938", The proceedings of the Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage Conference, Cape Town, 1997, pp. 207-208.

57H.F. Heese, "Khoisan in Kannaland: Observations by the German Lutheran Missionaries, 1838 to 1938", The proceedings of the Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage Conference, Cape Town, 1997, p. 186.

58H.F. Heese, "Khoisan in Kannaland: Observations by the German Lutheran Missionaries, 1838 to 1938", The proceedings of the Khoisan Identities and Cultural Heritage Conference, Cape Town, 1997, p. 210.

59C. Ziervogel, Brown South Africa, Cape Town, 1938.

60R.E. van der Ross, Coloured Viewpoint, a series of articles in the Cape Times, 1958-1985, Bellville, 1984, p. 96.

61A.C. Nissen, "An investigation into the supposed loss of the Khoikhoi traditional religious heritage amongst its descendants, namely the Coloured People with specific references to the question of religiosity of the Khoikhoi and their disintegration", Unpublished MSS-thesis, University of Cape Town, 1990, p. ix. https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/21841?show=full (accessed 2.9.2018). Chris Nissen is presently a South African Human Rights Commissioner.

62N. Trantaal, Wit issie 'n colour nie, Cape Town, 2018.

63Hanlie Retief in discussion with Willa Boezak, Rapport, 20.8.2017.

64M. Adhikari, "Not Black Enough': Changing expressions of Coloured Identity in Post-Apartheid South Africa", South African Historical Journal, 51, 2004, p. 176; see also H.F. Heese, "Malgassiese slawespook moet plek in die geskiedenis kry", Forum Article, Die Burger, 9.10.1996.

65M. Adhikari, "Not Black Enough': Changing expressions of Coloured Identity in Post-Apartheid South Africa", South African Historical Journal, 51, 2004, p. 177.

66"Khoisan-'koning' se hy stig af, wil Cyril uitskop", Die Burger, 18.7.2018. The flag sported the old South African orange, white and blue colours with a springbok, bow and arrow and four stars added.

67Le Fleur (or Lafleur) is a typical slave name. In 1834 one Le Fleur and 10 La Fleur slaves, all from Mozambique, were living in the Stellenbosch district. See Cape Archives, Slave Compensation Rolls, SO 6/80-SO 6/104, Cape Town, 1800.

68Under apartheid South African citizens were "racially classified" into the following categories: White, Cape Coloured, Malay, Griqua, Chinese, Indian, other Asian, other Coloured. The "race" of individuals was indicated in their official identity documents by a series of codes, starting with 00 for "White" and ending with 07 for "Other Coloured".

69"Vurige debat in laaste sitting oor onteiening", Die Burger, 6.8.2018.

70R.E. van der Ross, Say it out loud, The A.P.O. Presidential addresses and other Major Political Speeches, 1906-1940 of Dr Abdullah Abdurahman, Bellville, 1990, p. 3. See also in this regard: R.E. van der Ross, Up from slavery: slaves at the Cape, their origins, treatment and contribution, Cape Town, 2005. Personal communication, Stellenbosch, 2014.

71A survey of the Afrikaans newspaper Die Burger from 2016 to 2018 reveals that the term "Bruin" (Brown) is now the accepted term to refer to Cape Coloured people in Afrikaans; at least in the printed press. The potentially politically offensive term Kleurling (Coloured) has been dropped for some years.

72Was sind das fur Menschen, diese "Farbigen"? G. Brennecke, Bruder im Schatten, East Berlin, 1954, p. 19

73G. Brennecke, Bruder im Schatten, East Berlin, 1954, p. 20.

74J.L.M. Franken, Taalhistoriese Bydraes, Cape Town, 1953, pp. 41-79.

75C.R. Boxer, The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415-1825, London, 1977, pp. 249-272.

76M.C. Botha, "Blood group gene frequencies", Addendum, South African Medical Journal, April, 1972, p. 1; Migration patterns after the 1960s may have drastically altered the genetic and DNS composition of the coloured population of Cape Town. Botha was the immunologist of the pioneer heart transplant team of professor Christiaan Barnard in 1967.

77During the 18th century a number of Chinese lived at the Cape as exiles from Indonesia. A few of them owned slaves and it can be assumed that they did not lead celibate lives. Rijksarchief, The Hague, VOC 4183, Tax Roll for Cape Town, 1751. No fewer than 18 Chinese are listed as members of the free community in Cape Town and liable to pay taxes.

78See the submission of (Khoikhoi) Chief Joseph D. Little, NKC Chairperson, 12 July 2003, listed as A submission on the traditional leadership and governance framework bill called for by the portfolio committee of parliament of the standing committee on provincial and local government, 11 September 2003; comments as per Gov. Gazette No. 25155, (2003).

79M. Adhikari, "Not Black Enough: Changing expressions of Coloured Identity in Post-Apartheid South Africa", South African Historical Journal, 51, 2004, p. 177.

80N. Trantaal, Wit issie 'n colour nie, Cape Town, 2018.

81According to Dr Ernest Messina, historian and founder member of the Black Business Forum, later also director of companies and until recently chairman of the AHI (Afrikaans Business Chamber), a few intellectuals of racially mixed descent still prefer the term "black" to "brown" or "coloured" ; Discussion with dr. Messina, Stellenbosch, 7 March 2020. That very few of the "intellectual elite" of the 1980s and early 1990s still adhere to the "black" identity of "brown" society, became apparent during a live radio debate on this issue on 10 March 2020 during the Afrikaans Word Festival at Stellenbosch. Participants included dr Lionel Louw, Allan Grootboom, Fatima Alie and former activist, Basil Kivedo, who stressed the Khoisan roots of "brown identity".

Corresponding Author

Hans Friedrich Heese, Research Fellow, Department of History, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Copyright

© 2020 Heese HF. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.