The Social Psychology of Violence on Children in an Urban School in Jamaica

Abstract

Introduction

Children living in violent communities across the length and breadth of Jamaica are particularly vulnerable to anti-social and criminal behaviours. Chuck [1] in his contribution on violence asserted that the present reality of violence has become the heaven for a wide range of emotional feelings ranging from discouragement, desperation, fear, anger, and depression which is not confined to any particular class or groups.

Aim

Therefore this study will concentrate on finding out how children who have experienced violence actually perform academically. The participants will be drawn from among fourth and fifth graders in a Jamaican primary school in an urban area. It is hope that this study will provide some insight for school administrators and stakeholders of the various strategies to which they can employ in correcting violence at school and changing the low academic performance of children who are exposed to violence in their communities.

Method

The data were analyzed using themes, and narrations, and they were presented in figures and tables as well as narratives of the participants.

Results

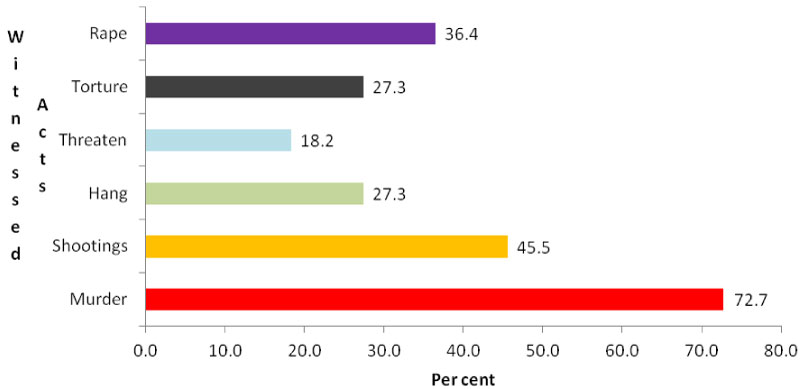

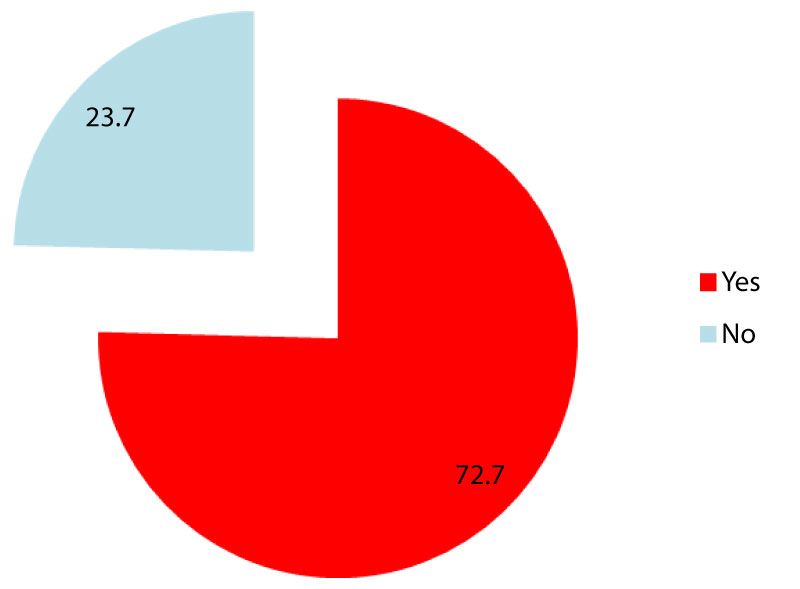

All the participants of the study stated that community violence range from the involvement of police officers and gang members, gang members and innocent community members, and internal as well as external gang violence. The two major themes emerged from this study are the 1) Gruesome acts of violence witnessed, and 2) Negative influence of witnessing violent acts.

Conclusion

A school with a robust process in place that routinely monitors students' behavior, consistently enforce the school's policies, and regularly communicate the expectations to staff, students, and parents can dramatically improve the quality of their school climate.

Keywords

Violence, Community violence, Academic performance, Home violence

Background

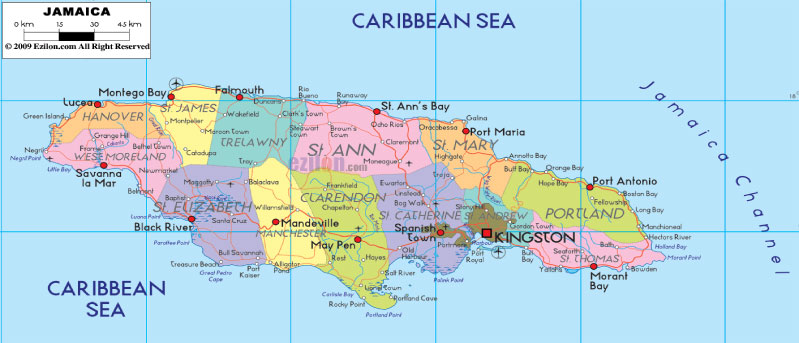

The issue of violent crimes has become pandemic in the Caribbean, especially Jamaica [2-5]. The crime phenomenon in Jamaica is so widespread that in 2007 a national probability survey that was done by [6] revealed that crime and violence were the leading problems identified in Jamaica. The statistics, showed that murder is the leading form of violence and that it continues to be a challenge to policy makers [7]. In another study done by Bourne, Hudson-Davis, Sharpe-Pryce...Nelson [8] found that 44.2 per 100,000 Jamaican was murdered in 2013 which makes this country the sixth with the highest number of murders in the world. In an empirical study conducted by [9-11] revealed that murder is linked to other health issues; and that there is a correlation between murder and poverty, ill health and violent crimes. According to Bourne and Solan [10] "The nexus of violent crimes in Jamaica goes back to pre-emancipation, when the revolt of the slaves would lead to their capture and murder" (p. 59), suggesting the long standing problem with crime and violence and survivability. Crime is, therefore, at a pandemic proportion in Jamaica, and it has infiltrated schools which is equally the case in other geo-political areas in the globe [12-16]. The reality, therefore, is children who are exposed in violence at their homes and/or communities are performing academically at a lower level than expected of them [14].

Children living in violent communities across the length and breadth of Jamaica are particularly vulnerable to anti-social and criminal behaviours [17-19]. Chuck [1] in his contribution on violence asserted that the present reality of violence has become the heaven for a wide range of emotional feelings ranging from discouragement, desperation, fear, anger, and depression which is not confined to any particular class or groups [20].

The passion to conduct this study came as a result of my close observation of many students who are exposed a high level of violence in communities such as St. Johns' Road, Homestead, Red Pond, and Irish Pen and how there is a high absenteeism among these pupils when violence erupts in their communities. In addition to their low academic performance. Besides the physical harm violence causes our children; there is also the psychological distress associated with it. It is important that the social environment be free from fear that children can feel safe. This is only achievable if the worsening trends of violence be eradicated in society. It is the belief of the researcher that teachers and students alike should be able to perform in a safe setting conducive to the teaching-learning process. Therefore this study will concentrate on finding out how children who have experienced violence actually perform academically. The participants will be drawn from among the grades 4 and 5 classes in a Jamaican primary school in an urban area. It is hope that this study will provide some insight for school administrators and stakeholders of the various strategies to which they can employ in correcting violence at school and changing the low academic performance of children who are exposed to violence in their communities.

Schools have been portrayed by many students and their parents as unsafe places, that are frequently characterized by rapes, shootings, stabbings, beatings, bullying, and other social deviant acts [12,21,22]; there is also reported cases of violence against teachers by students as well as their parents and associates [17,18]. These occurrences of acts of violence in the form of verbal threats, cursing, name-calling, or fights is more frequent in schools than homicide [15], making schools unsafe places for young minds. Grumpel and Meadan [23] stated that although there is widespread violence in schools, and it has been receiving much attention, there is still a lack of clarity as to what constitutes school-based violence. This, some believe, may influence the reporting of prevalence rates. Batsche and Knoff [16] stated that school violence is usually defined by acts of assault, theft, and vandalism or acts that may not be intentional but cause fear in either teacher or student. Gumpel & Meadan [23] further classified aggressive behaviors as either acts that are clearly violent as in the case of those inflicting bodily harm or the psychological which consist of those including teasing, bullying, or name-calling.

Statement of the Problem

The research team as well as a family member has taught at schools in violent prone communities for over twenty years. Over the two decades, the school has had to close its door when violence commences in the surrounding communities. In fact, there have been many occasions in which the violence begins in the adjacent community and then is played out on the school's compound. There have been a few occasions in which students and teachers had to lay on the classroom floor for fear of life. Owing to what obtains sometimes during the nights children are unable to complete assignments because they must turn off the lights when the violence erupts in the community. In fact, there was one year in which the violence in the surrounding communities to the school affected examination including Grade Four Examination, and the Grade Six Achievement Test (G-SAT). During periods in which violence commences in the neighboring communities to the school, especially the adjacent areas to the school, there is heightened fear among teachers, students, administrators, and other staffers at the school. This leads to interruption of the functioning of the school, no teaching or learning can go on and syllabi are not completed for the specified time. The reality is, violence in school and the general community in which the school exists retards the teaching-learning process, and does account for the lower academic performance among pupils at a school.

A study conducted by Baker-Henningham, Meeks-Gardner, Chang, and Walker [24], investigated the experiences of violence and the deficit in academic achievement among a cross-section of urban primary school children in Jamaica and some potent findings were revealed thereby. Their study confirmed that there is a correlation between primary school children's experiences of three different types of violence (exposure to community violence, and exposure to aggression among peers at school), and their academic achievement. Such a finding provides a rationale for the researcher want to examine the role of violence on academic performance of pupils who attend a primary school that is situated in a violent prone community in urban St. Catherine.

Methodology

A research process constitutes identification of a problem, literature search, methodology and method, data collection, analysis of data, collation of the research, and so forth, with the methodology being a critical component of the process. Within the context of the previously mentioned issue, this research employed mixed methodologies - quantitative and qualitative methodologies. The rationale behind the mixed methodology is simply the drawbacks in one method can be enhance by the strength of another method. Many scholars [25-27] noted that mixed method lends itself to triangulation of findings, in-depth analyses and therefore is the best approach to the research agenda. For this research, the research will employ 1) Survey research - via a standardized questionnaire) and 2) Phenomenology - by way of elite interviews and/or focus group discussions.

Purpose of the Study

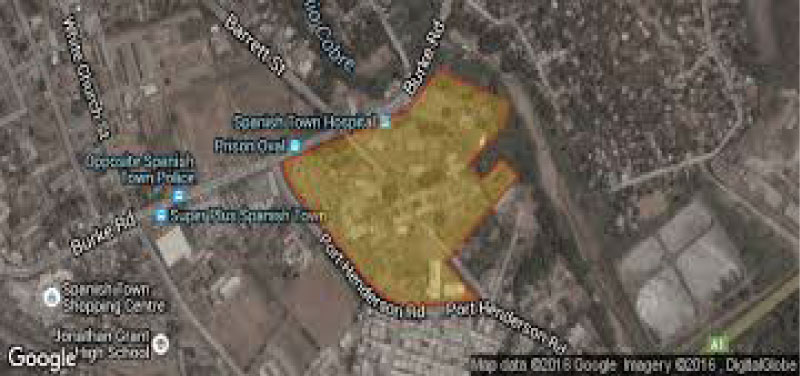

The primary purpose of this exploratory study is to explore reasons for poor academic scores and academic success among a group of fourth graders and to implement strategies to improve school performance. The population consists of students from the primary classroom and from this a purposive sample of ten will be selected for the intervention. The students live in violence prone communities in Spanish Town, St. Catherine during the period January 1-to-January 20, 2017. The researcher also informed the principal of one of the benefits of this intervention programme which is to help administrators to make meaningful decisions as to which teaching approach would best fit the subjects in order to improve performance.

Main Research Questions

How does community violence influence the academic performance of a group of primary school students who live in violence prone communities in Spanish Town, St. Catherine during the period January 1-to-January 20, 2017?

How does community violence influence the behaviour of a group of primary school students who live in selected violent prone communities in Spanish Town, St. Catherine during the period January 1-to-January 20, 2017?

Significance of the study

Harriott [28] posited that research is critical to effective policy formulation. His perspective provides the most significant basis on which this study is justified. It is anticipated that the information gleaned from this study will be used to sensitize parents, school administrators, guidance counselors, and teachers on the many problems facing children as a result of their exposure to violence.

The actual information garnered from this study will be made available to the Ministry of Education with the hope that it will influence the types of early childhood, primary, and secondary programme/curriculum planned by the Ministry of Education for schools. Secondly, that findings from this study will focus on the need for government to employ trained school psychologists beginning from the early childhood, primary and high school levels; to assist parents whose children will need to be tested.

Limitations

The use of non-probability sample means that the research is non-generalizable and as such the findings cannot be replicated to other samples. Nevertheless, the results for this study provide depth insight into a matter can be studied for a generable perspective.

Operational definition of terms

Gay and Arasian [29] stated that "operational" variables serve to clarify the meaning of important terms in a study so that readers will understand the precise meaning the researcher intends (p, 64). The researcher is aware that there are other definitions for some of the terms used but wishes to clarify these used in the study.

• Violence: Is defined as behaviour involving physical force intended to hurt, damage, or kill and an infringements of basic rights, verbal and emotional aggression to inflicting physical harm [30,31].

• Family Violence: Is defined as any deliberate act intended to harm members of the family whether be it physical, emotional or verbally [32].

• Child maltreatment: Includes neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse or sexual abuse defined as inappropriate exposure of a child to sexual acts or materials, passive use of children as sexual stimuli for adults [33].

• Nature: Refers to the inherited or genetic characteristics of a person [33].

• Nurture: Refers to the characteristics of a person's environment that affect development [33].

• Family: People who are biologically related with each other.

• Community violence: Is defined as sexual assault, burglary, use of weapons, the sounds of bullet shots, as well as social disorder issues such as the presence of teen gangs, drugs, and racial divisions [34].retrieved from www.nccev.org

• Academic functioning: Is define as the child's ability to demonstrate or perform cognitive activities such as problem-solving, classifying, comprehension, written language communication, reading, mathematics and general information at the age appropriate content (adapted from the 1992 American Association of Mental Retardation, AAMR). For this study, it is measured by way of the evaluation of a standardized test. In addition, failure or poor performance is score below 60%.

• Resilience in children: Is the ability of a child to respond to the realities of life's barriers and to use them as stepping stones to development and success.

• Temperament: Defines an individual behavioural style and the way of responding emotionally to any event [35].

Summary

Children are a product of their social milieu, which means that the underperformance of pupils at the primary educational level must a by-product of the general society. The underperformances of Jamaican candidates in Mathematics and English Language are clear indicators of violence in the home as well as the community including school. The complaints of managers about the quality of the human stock in Jamaica are in keeping with the general social confusions, role-crossing and deficiencies in expectations. The research by Powell, Bourne and Waller (2007) which identified the travails in the educational system in Jamaica is a wider social issue. Clearly, the answers to the underperformance of Jamaica students in various subjects must be tackled from a social context, and this study will provide the ingredients for such dialogue and actions. The dismally low performances of Jamaican primary school require urgent attention, and this research seeks to provide a social context for the matter and the way forward. This paper is sub-divided in five chapters with the remaining being literature review, methodology, findings and discussion of the findings in context with the literature as well some meaningful recommendations.

Literature Review

The literature review sets the broad concept for examining the issues surrounding a particular theme, allows for the building block of research questions and provides a platform for embarking on new ideas [36]. Hence, this chapter, literature review, plays a critical role in the research process and cannot be excluded from a research. Therefore, this paper examines violence in environment including the community and home and how it influence academic performance of students. As time progresses, violence has increasingly become more prevalent in society and its tenets far reaching to include children. As a result, the family setting would feel some amount of the backlash. Violence is experienced in many forms. Instances of violence include sexual, physical abuse, emotion abuse, television violence, family violence and community violence. In an effort to establish transparency, the review will encompass five major captions. Namely:

1. The theoretical framework of the study

2. The consequence violence in the family has on children

3. The structure of the family as it relates to exposure to violence

4. Family Functioning and its exposure to violence

5. Is a child's academic performance impacted by experiences of family and community violence?

Theoretical framework of the study

Crotty [26] pointed out that the research process begins with an epistemology followed by a theoretical perspective, methodology and method. He continued that the theoretical perspective is "The philosophical stance informing the methodology and thus providing a context for the process and grounding its logic and criteria" [26]. In keeping with Crotty's perspective, the researcher therefore employed a theoretical framework because of its significance to the research process. Hence, the ecological and nature versus nurture theories are used to form the theoretical perspective for the current work: 1) The ecological theory and 2) Nature verses Nurture theory.

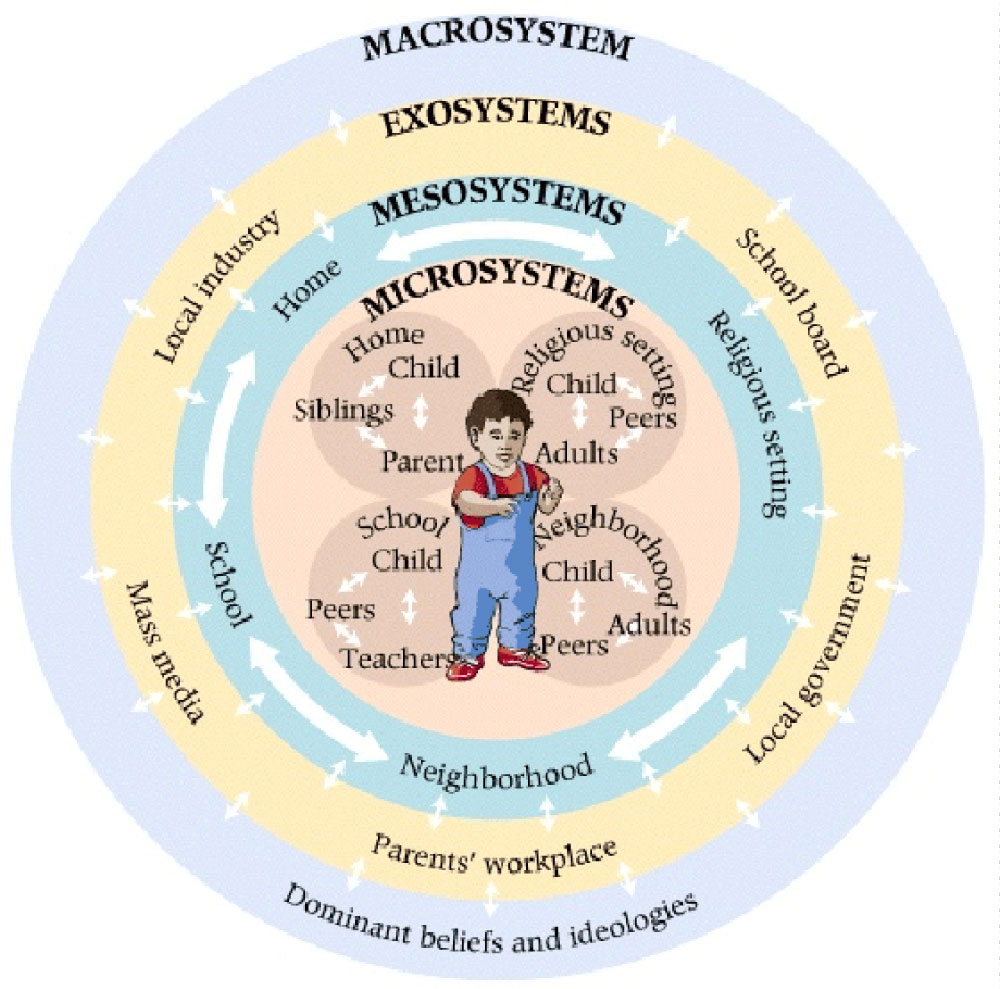

The ecological model: In 1979, Bronfenbrenner developed a model which placed much significance on the role the environment plays in the development of a child. Based on his theory, the entire development of the child occurs through relationships experienced through a variety of environments that exists. The micro-system, meso-system, exo-system, and the macro-system forms the four pillars through which the child is believed to interact in. The most direct, interactive and influential environment is the micro system. This system covers the interaction between the child and family members, caregivers, religious setting, school and neighbors. The micro system is of such influence, that it can directly influence the formation of a child's personality negatively or positively.

The second of the four pillars is the mesosystem, which Santrock [35] thought it to be the relationship that exists in the micro-system. For example, parents lay the foundation of religion in the home. This is followed up by attending their place of worship at the appointed time based on that particular religion. The parent would give guidance and follow up the child's progress. In contrast to the connection of the child's mesosystem, in accordance with the risk factors that are present, violent tendencies and behaviors might occur.

The third and penultimate pillar is the exosystem which speaks about the child's interaction with society. The child's role is an interactive one at best; however, it is the society that influences the child's experience. A child who lives in a very peaceful home for example is likely to relate to peers in the same manner. However, a child who has a father who is a gang leader in his community can be expected to display violent behavior.

The fourth and final pillar is the macro system, deals with the rite of passage. Values, attitudes and cultural norms are conveyed to the child by the general community. This also indirectly influences how the child interacts on a day to day basis with significant others. The home, school and community all provide influences for positive or negative patterns through interaction. All in all, the development of the child is assessed within the confines of an environment and the relationships within that environment. One must pay attention to all the factors of stress in the surroundings in order to grasp the concept of family and community violence. One can justify that the methodology within the confines of an ecological framework is most useful as it relates to child development (Figure 1).

Nature versus nurture theory: It was thought many decades ago that one's biological instinct was the major influence in an individual's behavior. It is now understood that one's behavior is as a result of the social environment that he or she encounters. Hereditary traits are what come to mind when one thinks about nature, while one's experiences in any given environment is credited to nature. This means that theoretical analysis is provided which deals with biological outlook as it regards to birth defects and the impact of cell development. Its analysis also extends to the impact that factors such as family dynamics, gender, parenting, school and neighborhood quality play in the development of the child and there temperament. So much so, that Malley-Morrison claimed that legitimacy is established in many cultures as rage and aggression are regarded as values which are displayed as strong biological components.

Santrock [35] went one step further as he made reference to Krause, Bronfenbrenner and Morris's claim. He did so by establishing an extension of one's biological environment which includes nutrition, medical care, drugs and physical accident. The interaction between both nature and nurture is of utmost importance in the developmental path of the child. This is especially noticeable in between mother and child. Collin and Seinberg states that an adolescent is less likely to become a drug addict or engage in acts of delinquency if he or she is effectively monitored by parents. Patterson [33] spoke about creating a perfect habitat student development. He added that harmonizing family school and culture would provide the optimal climate for students to achieve.

The consequence violence in the family has on children

Firstly, one must understand that family violence is one of the most prevalent acts in our society, and that everyone at one point or another is affected by it [36]. For an act of violence to be categorized as family violence, there must be a deliberate intent from at least one family member to harm another member of the family [37]. This may occur in the form of; child maltreatment, spousal abuse or abuse to the elderly. Wilson stated that isolation and hopelessness are often displayed by children who experience violence, regardless of what age they encounter it. He went on further to say that these children will also display acts of violence as a means of solving problems. He also went on to say that these children experience intense levels of anxiety and will ultimately experience retardation in their development. A year later Weihe [32] stated that academic disturbance may come into play if children are consistently exposed to violence. This according to Weihe [32] occurs because children loose considerable amounts of school time by trying to escape violence. Some children may attempt to run away, or move in with other family members, leaving behind documentations that are essential for school, such as; immunization cards and birth certificate.

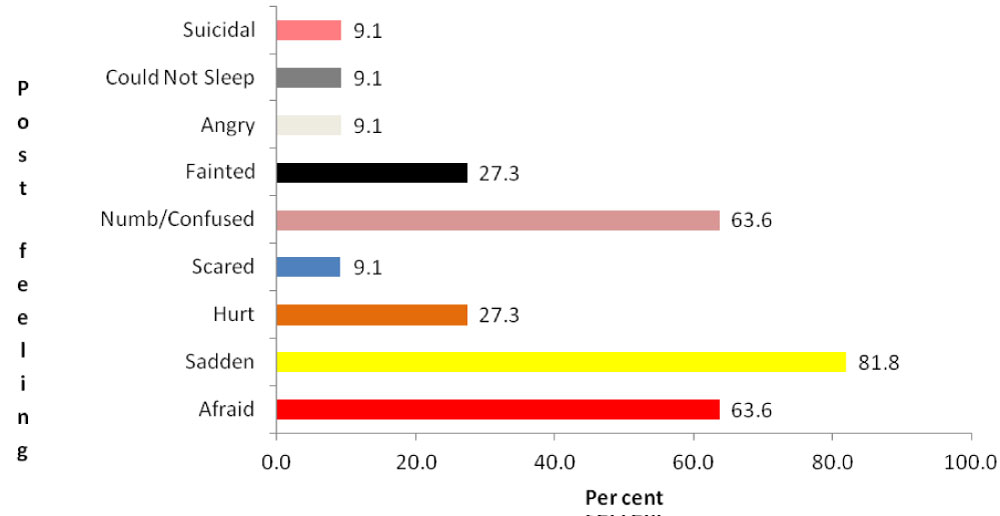

Long term effects of violence on children who are exposed to it: The effects of violence on children are quite often neglected, especially when the child was not the direct target of abuse. However, post-traumatic stress disorder is quite common in children after exposure to violence. Such disorder includes; bed wetting, nightmares, insomnia, reduction in verbal, cognitive and motor abilities and depression [34,38,39].

Short term effects of violence on children who are exposed to it: The short term effects of violence on children are easily identifiable traits. According to Wiehe [32] children who are exposed to violence are likely to perform poorly academically and tend to lose newly acquired skills. Isolation comes into play and the child develops a short attention span.

How community violence affects children: It is often said that children are like sponges. They are ready to absorb whatever lessons there are to learn. As such, they tend to imitate adult behavior. Acts of violence in communities include burglary, sexual assault, shootings, stabbings and extortion to name a few. These examples can often be found in schools, because in most cases children learn these practices in the communities first. Thompson and Massat [38] found in their research that children who were exposed to violence displayed some levels of post-traumatic stress. Chevannes's [40] in a local study found that boys who participate in violent activities pay an even higher price. His study showed that boys who are involved in community violence would stop participating in predictable activities, such as attending school, for fear of being pounced upon by other gang members on the road. It would also seem that the perpetual cycle of males participating in criminal activities will continue indefinitely according to Chevannes [40]. His study showed that fathers in many instances were forced to flee their communities for fear of losing their lives. This in turn leaves children fatherless.

The structure of the family as it relates to exposure to violence

Much importance is placed on having a nuclear family throughout the Caribbean [41]. Despite this fact, there are many families with single parents in cohabiting unions, households with none biological siblings and children with none related guardians. It is not difficult to perceive that the quality of the home is crucial in the emotional development of a child. Cases where there have been one or both parents going abroad and leaving and older sibling in charge, tends to result in instances of physical and, or verbal abuse. The younger sibling will also fall short of the nurturing that is needed. This is due to the fact that older siblings, though seemingly responsible are ill-equipped to handle the pressures of parenting. It is in a family setting that a child first learns how to show affection. It is during this crucial period that the child learns right from wrong and their development can be a positive or a negative one.

Family functioning and children's exposure to violence

One cannot assess family functioning and its exposure to violence without considering the psyche of the child. This is due to the fact that the child's first sociable interaction comes from within the family unit. It is through this interaction that self actualization is given birth. Children exposed to violence and dysfunctional family settings, usually become deviants [42]. These individuals would also display signs of low self esteem and high rates of psychiatric illness. The role of the family is of such importance, that it "exerts the greatest amount of influence on the lives of children" [17]. This is due to the fact that it is in the setting that values and attitudes are learnt and prejudices about themselves and others are displayed. Many researchers have come to realize that the family setting gives major insight as it relates to research on mental health.

Risk factors that contribute to students' involvement in violence: Risk factors relate to those characteristics of the person or the environment that are associated with an increased chance of maladaptive behaviour occurring. The contributors to violence in schools are viewed as a reflection of what takes place in the communities, the home, the media and the school environment. It should not be surprising then, that an increasing number of students are involved in violence in one way or another as victims or perpetrators. Social learning theory posits that people acquire aggressive behaviours through observing and imitating [43]. This shows that violence is a learnt behavior. Hawkins and Catalano [44] have identified several risk factors in young people that are predictors of later violence and antisocial behaviour. Among these factors was alienation which was linked to a lack of bonding to school, family and community stress. They believed that learning prosocial skills not only helped young people with their interpersonal relationships, but with their attitudes towards school as well. Such improvement would yield higher academic achievement and a more cooperative school climate. This would help to erase the negative and antisocial behaviour which students had. They stated that it was important not only to see the skills modeled but that they are practiced in a setting where feedback and reinforcement were provided for the choice of skills. In Jamaica there has been attempt by programmes such as Peace and Love in Schools (PALS) and Change from within which teach skills to deal peacefully with conflicts.

An article by Prevention Institute (2001) concluded that the frequency of an individual's exposure to risk factors predisposes him or her to the probability for increased engagement in violent behaviour. These were listed as individual factors, school factors and community factors.

Individual factors included poor academic performance, poor use of unstructured free time as well as delinquent peers. School factors had to do with the size of the school population, geographic location and gangs. The larger the school population the more likely it was for occurrence of violent acts. Schools situated in urban areas were more prone to report serious violent acts compared to those in more rural areas. In communities a lack of inadequate social amenities brought about a feeling of societal neglect by students. Their anger and frustration were vented by violence.

Violent behaviour was portrayed by the media as an appropriate way to solve problems. Young people therefore became desensitized to and accepted violence. The use of guns was yet another factor as the easy access to weapons increased its use. Like most other views expressed, students were most likely to be violent if they were witnesses of violence or were subject to childhood abuse. Students came to see the world as a dangerous place. To survive one had to be prepared to react to adverse situations which were always present. Such an attitude promoted a sense of defensiveness, suspicion, the need for standing one's ground and inclination to offer reprisal for the slightest offence.

Other underlying factors were poor financial situation, stressful family environment with lack of proper role models, conflict in the home and poor communication skills. Mental illnesses and mental disorders impaired students' ability to communicate and make right decisions. They were therefore at an increased risk of being perpetrators or victims of violence. Fernald and Meeks- Gardner [18] cited that in Jamaica although students are exposed to violence those in the inner cities are exposed to greater levels of crime and violence. These students prove to be more aggressive and resort to violence to settle their problems.

Leone, Mayer, Malmgren and Misel [45] noted that hyperactivity, limited attention span, restlessness, poor social skills favor the development of delinquent behaviour. The beliefs and attitudes of some students dictated that there should be retaliation for any and every situation. In addition students with certain disabilities for example emotional disturbances, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and specific learning disabilities were more likely to display antisocial behaviours.

Conditions in the home provided early onset of chronic patterns of antisocial behaviour. These were linked to harsh and ineffective parental discipline, lack of parental involvement, family conflict, parental criminality, child abuse or neglect [14]. Williams points out that Jamaica is primarily a matriarchal society. The absence of fathers in many households negates positive parental values particularly to the males. The increasing number of teenaged mothers heightens the problem of children being given proper parental guidance.

Cole [46] believed that students were increasingly coming from backgrounds where antisocial behaviour was more the norm than the exception. The students were highly agitated and invested in antisocial attitudes and beliefs which made the use of antisocial solutions to interpersonal conflicts legitimate. They tend to see the behaviour and intentions of others as being biased against them. This bias helped to distort the ability to decode and interpret the social behaviour of others in a positive way. They frequently react aggressively to situations they view as challenging or threatening.

Shafii and Shafii [13] stated that children learnt to resolve their own problems through the use of violent strategies which they see being used. They imitate the behaviour of others and receive positive reinforcement from their peers when they deal with interpersonal conflict in a positive manner. Based on the background many children experience, some of them will resort to violence when they have exceeded their tolerance of frustration. Portrait reports that many of the young people report a history of violence in their lives. It is further reported that at sometime they thought about hurting or killing someone. This reinforces that when violence is experienced, whether as victim or perpetrator there is the increased risk that an adolescent will resort to violence against others.

Skiba and Peterson [47] showed that influences in the school and community helped to establish patterns of aggressive and violent behavior. Low school involvement, academic and social failure were some of the school factors named. There was failure to carry through rules as well as poor or inconsistent administrative support. In addition disciplinary practices in many schools were inconsistent and inequitable. Students from communities in which there was a lack of programmmes whether recreational or after school were prone to adopt violent behaviours. The absence of mentors helped to foster an adherence to antisocial behaviours. A lack of emotional or financial support may be gained through involvement in antisocial behavior.

Steinberg [48] examined the role of the family as a contributor to violent behavior in children. He stated that exposure to violence or abuse in the home, exposure to hostile punitive parenting or growing up in a home environment in which parents were not sufficiently involved in the child's life were among the most important risk factors for the child's subsequent involvement in violent and other types of antisocial behaviour. He looked at the role of the family from six perspectives. These are modeling, biological factors, and mental health, parenting personality development, academic performance and peer pressure.

Biological factors relate to early abuse and neglect. He pointed out that poor prenatal care, or pre-natal exposure to drugs could alter brain development. This led to some children having more difficulty containing aggressive impulses. Children whose parents were hostile and punitive as well as those whose parents were neglectful were at risk for developing all sorts of mental health problems. Children with mental health problems were at risk for developing patterns of antisocial and violent behaviours.

Negative parenting impaired proper personality development in children. They not only developed problems in controlling their emotions but also developed a biased way of looking at the world. They perceived that all people's actions were intentionally hostile when in fact they may not be so. Children who had problems in schools often gravitated towards groups of other troubled children and these peer groups frequently became involved in antisocial behaviour. Adolescents looked to their peers for support. It was easier to display antisocial or violent behaviour when with their peers that they would not do if they were alone. Adolescents who had strong positive relationships at home were more able to resist peer pressure. In contrast a lack of parental involvement or supervision placed the child at risk for involvement in antisocial peer activities and increased the youngster's vulnerability to negative peer influence.

He showed that adolescents who had the greatest number of problems with antisocial behaviour, personality development and in general mental health, came from families in which parents were hostile, aloof and involved. Many parents have abandoned their role and children are either left on their own or with relatives. Often these children do not learn positive values and resort to anti-social or delinquent behaviour.

Parental aggression, hostility and disengagement were good precursors of many problem behaviours. Children were more likely to show psychological problems both in terms of misconduct, and types of distress. They proved to be less interested and successful in schools. The television and other media were frequently blamed for today's epidemic of violence. The absence of fear, grief, remorse and consequences for violence on television, in movies or music sent a wrong message. They showed that violence was an acceptable way to solve problems as well as a symbol of power. The brutality depicted was unhealthy and even dangerous. Donnerstein, Slaby, and Eron stated that persons who viewed a lot of violence on television began to see the world as a mean and scary place where aggressive acts were acceptable means of solving problems.

Beresin stated that there appeared to be a strong correlation between media violence and aggressive behaviour. This he substantiated by stating that over the past 30 years longitudinal, cross-sectional and experimental studies had confirmed such a correlation. Children had access to television sets in their bedroom which facilitated the opportunity to view programmes without parental supervision. Heroes, the violent ones, were rewarded for their behaviour, becoming models for the youths. Children came to view violence as a fact of life became desensitized to it, ultimately losing their ability to empathize with either victim or perpetrator. The child rather than observing only became involved in acting out what is viewed.

Slaby maintained that violent students thought differently from their non-aggressive peers. Youths who were prone to violence sought fewer facts and had less insight into alternative solution. They often failed to anticipate the negative consequences of their behaviour. Violence in schools has several negative effects on students. Some of these are addressed in the next section. These students believe that if they are approached with violence they have to react violently otherwise they will be called derogatory names.

Impact of violence in schools: From the literature reviewed, violence in schools had varied and far reaching effects on students, teachers and the school system. The incidents of violence in schools not only posed a threat to the safety of teachers, students, and teachers but also proved to be a challenge to the authority of school administrators. Many teachers have been verbally abused, physically attacked or threatened by students or their relatives. If schools are to be safe there should be a lack of psychological stress and physical harm [49]. The antisocial behaviour of students endangered the safety of school personnel. Students and staff members suffered psychologically and physically because of violence in schools. Some incidents have been fatal.

It is believed that students feel powerless when attacked or provoked hence, they resort to violence when provoked in order to regain a sense of power [50]. This was evident in a series of school related shootings which took place in the United States. In schools in Jamaica incidents of shootings are few, the knife is widely used with frequent stabbings which occur, some of which are fatal. A report published by the National Association of State Board of Education of Virginia in 1994 outlined some of the effects on teachers, students and the learning environment. The report recorded examples of the negative, physical, social, emotional, cognitive and psychological effects.

Students who were victims of violence may exhibit feelings of fear, anger, sadness, guilt, and mistrust. Violent or disruptive behaviour could destroy a positive learning environment. The fear that was generated by the acts of violence inhibited the ability of teachers to teach and students to learn. Cognitively the students who were fearful may have trouble paying attention, concentrating and learning. In order to ensure the safety of children, parents might keep children from school, thus affecting school attendance. Some may even be permanently removed. From a social point of view students who had either witnessed violence or been a victim may be either disruptive or aggressive and had difficulty relating to other students. Psychologically behavioural disorders may occur. Schools were prone to suffer from a lack of extracurricular activities as a response to campuses being unsafe. Violence in schools therefore interferes with optimal learning as an atmosphere of fear is established.

Bullying which frequently occurred in schools was often taken lightly but could have serious effects. Students who were bullied may suffer from depression, low self-esteem or anxiety. The fact that students may feel unsafe at school significantly interfered with learning. Schneider outlined the effects of bullying which he defined as purposefully doing harm to others. This was facilitated through ever repeating physical assaults, verbal and physical intimidation, harassment and constant molestation. The damage to the victim was of a mental nature rather than physical. The humiliation lasted for years, with the victims suffering from reduced self-esteem. This could affect academic and social outcomes. Victims suffered from emotional and psychological trauma and in extreme cases were lead to serious violence. Rigby [51] showed that students who had been harassed by peers had suffered depression and experienced suicidal ideation. Olweus [52] reported that students subjected to frequent bullying often sought refuge from teachers during breaks, avoided restrooms and other isolated areas or made excuses to be absent from school. They appeared distressed, unhappy and depressed with evidence of deterioration in interest and performance in school.

Boivin, Hymal and Hodges [22] showed that there was a relationship between peer harassment and academic performance. Victims tend to develop negative attitude towards school and overtime school performance declined. Dodge, Bates and Pettit [53] concluded from studies done that abused children tend to acquire deviant patterns of processing social information. This fostered the development of aggressive behaviours. Harmed children had a bias to attribute hostile intentions to others and a lack of positive behavioural strategies to solve interpersonal problems. These patterns were found to predict the development of aggressive behaviours. The experience of physical harm led a child to conceptualize the world in deviant ways that later perpetuated the cycle of violence. The viewing of television violence overtime helps to reinforce hostile thoughts which the viewer might have had [54]. The viewer always seems to be able to recall the violent scenes in a graphic manner.

Osofsky [55] reported that exposure to violence could have significant effects on children during older development and as they form their own intimate relationships in childhood and adulthood. Although literature was produced on the various developmental stages, the literature relating to adolescents was found to be most relevant to this study. She posited that evidence from research revealed that adolescents exposed to violence particularly those exposed to chronic community violence throughout their lives, tended to show high levels of aggression and acting out, accompanied by anxiety, behavioural problems, truancy, school problems, and revenge seeking. Children exposed to family violence often displayed internalizing and externalizing behavioural problems in comparison to children from non-violent families. Internalizing behaviours included withdrawal and anxiety while aggressiveness and delinquency manifested externalizing behaviours. Overall functioning, attitude, social competence and school performances were often affected negatively. Longitudinal studies according to the writer had revealed that children exposed to media violence overtime were most likely to engage in delinquent and aggressive behaviour. Media violence may increase negative behaviour because of the potential for social learning and modeling of inappropriate behaviour. Even when fictionalized violence that was dramatically portrayed and glamorized was likely to have negative impact on children and increased their propensity for violence. Television programmes and movies show graphic acts of violence as well as provide violent role models with whom adolescents can identify. By observing models in violent and aggressive behaviors the children react in a similar way. Many of the themes portray jealousy, revenge and violence.

The long term viewing of television violence does have a negative effect on students as with a preference for "action movies" they can be seen acting out what is viewed. It should be noted however that if properly utilized and if guidance is given during viewing the television can be used for educational purposes. Hawkins [44] addressed the aspect of resiliency. He defined resilient persons as those who were exposed to potentially damaging environments, events or circumstances during the course of their development they were either able to resist them or overcome the effects of the high risk conditions. They have been identified as possessing among other qualities strong social competence and problem solving skills. This demonstrates why some students although faced with risk factors which promoted violence do not become violent or aggressive.

Christle, Joviette and Nelson looked at certain protective factors which account for one to be exposed to risk factors but do not display aggressive and violent behaviour. Like risk factors, protective factors may be strengthened through interaction with other factors. These include individual, family, school and community factors. Individual factors include having a more positive view of one's life circumstances and stress reducing strategies. Family protective factors are viewed against the background that there is an attachment to at least one family member. This member not only provides a sense of belonging but shows the child that he or she is valued. In the schools both teachers and administrators can assist by providing a positive and safe learning environment. There should be the setting of high yet achievable academic and social expectation. These should be facilitated. Students should be encouraged to be members of groups in the school as this would help to deter demonstration of aggression or violence. The social structure in the communities could help to prevent students from engaging in antisocial and violent behaviour.

Strategies to decrease incidents of violence: In order to decrease the threat posed by violence in the schools, many strategies have been utilized. This range from punitive to the more humane ones which include counselling and the teaching of conflict resolution skills. Skiba and Peterson [56] outlined the many strategies, which were being implemented to help with the prevention or decline of antisocial or violent behaviour. These included the use of metal detectors, security guards, dress codes, zero-tolerance policies resulting in suspension or expulsion for certain types of aggression or threatening behaviour. Strategies for identifying students most likely to commit violent acts were formulated. The use of strong disciplinary tactics in response to disruptive behaviour was maintained.

Mulvey and Cauffman [57] stated that despite the violence which occurred in schools, these institutions had proven to be one of the safest places for youths. The fact that violence does occur in schools had led administrators to devise various strategies to stem the incidents of violence. Some of these they believed did more harm than good to the students. Their focus was on the strategy aimed at identifying and intervening proactively with potentially violent students. This they thought posed several challenges. The nature of the problem may have social underpinnings and to focus solely on the individual would not achieve the desired result. Adolescents they stated were still undergoing developmental changes hence their characteristics were not fully formed. They reported that although it was not clear which intervention worked, the ones which focused on building specific skills were more likely to work. There should be on going evaluation of the factors which increased or decreased the likelihood of one being violent. Students should be encouraged to give information on students who were facing problems or prone to violence. This could only be achieved however, if there was a supportive and healthy school relationship. This would foster a sense of belonging, and decrease any feeling of alienation. Students would then feel freer to give information. On the contrary students felt mistrusted and uninvolved when administration adopted a zero -tolerance approach.

Lantieri and Patti [58] described a programme which recognized that the ability to manage emotions, resolve conflicts and alleviate biases were fundamental skills to be taught. Schools which were viewed as being able to perform a socializing function in students were able not only to nurture their thinking abilities but to practice handling their emotions learn how to deal with conflicts and gain exposure to societal values. To achieve this however, the skills for improving emotional competence should be taught.

Norguera [59] stated that the search for solution has generated many strategies. Some of these were coercive and harsh while others were more humane. There had been a preference however for the harsher ones in an effort to maintain authority, power, and control. Some of the more popular measures include the enactment of zero tolerance policies which serves to remove students who are involved in violent acts. The methods used are through suspensions, suspensions or transfers. Besides the use of these strategies, violent act or even non violent ones are treated as criminal offences. Despite the drastic approach being taken schools were still unsafe. The use of coercive methods interrupted learning and produced an environment of mistrust and resistance. Although schools had undertaken less coercive measure such as mentoring and the teaching of conflict resolution skills. The introductions of conflict resolution programs were instituted to teach students to settle their disputes in a non-violent manner. Through the use of adults as role models students are counseled and provided with a supportive environment.

The focus however is on the use of harsher methods. The contention was that violence must be countered with force. For schools to be safe it was assumed that they have to be like prisons, to identify, apprehend and get rid of students who are potential perpetrators of violence. In an effort to highlight the success of the various methods statistics are used to show the number of weapons confiscated and students expelled or suspended. The strategy employed was either to quantify the result of their effort or not to present at all, the latter being used because a lack of information being transmitted would suggest that violence was under control.

The extent of violence in schools in Jamaica: A study by Soyibo and Lee [12] among high school students revealed that 27% of the participants had caused injuries to persons, 59.5% used weapons and techniques during violent acts including use of hands or feet, 59.1% used nasty words, 54.5% used punches and kicks, 26.5% used blunt objects, 18.4% used knives, 9.3% used ice-picks, 8.9% used machetes, 8.5% used scissors, 7.5% used forks, 6.9% used guns, other weapons (bottles and dividers) 6.7% and 5.5%.

Callender who conducted a study in schools in Jamaica's capital found that 70% of students had seen fights in which a weapon was used. The knife was the most frequently used. 32% of students had been hurt in fights and needed treatment by the teacher. 50% of students reported that other students had deliberately damaged their property. Meeks-Gardener [60] found that 83.7% of a sample of 1710 knew children who took weapons such as a knife to school. 80% said children in their class fought a lot and were worried about violence at school. 40% reported that students threaten teachers with violence. 21% reported that students have actually attacked teachers at their school.

The Jamaica Teachers Association, the body which represents the nation's teachers has constantly voiced concern regarding the present spate of violence in schools. Several factors have been put forward. These include presence of gangs, violence in communities, extortion of students by students, lack of furniture, shoot outs in garrison communities and a lack of proper fencing. Incidents reported to the Association revealed that between September 2002- May 2003 fourteen teachers were attacked by students, three by the community and twelve teachers suffered injuries on the job. Over this same period twenty-eight students were attacked by other students, eight by members in the community, while thirteen were injured at school. Three students were killed at school over this period (J.T.A. Reporter, p 24). As impressive as the above statistics might appear they do not reveal a true picture of the extent of the violence that takes place as not all incidents are recorded. Most often, the more serious incidents are the ones which are recorded or gain public attention. Incidents of violence in schools occur on a daily basis, whether it is bullying, quarrels or fights.

Evaluation of strategies implemented to decrease incidence of violence: Although there is evidence to show that punitive methods have been widely used, studies have shown that they are not very effective means dealing with violence. In some cases it is thought that it exacerbates the problem. Suspension and expulsion are seen primarily as increasing the risk of disruption of one's education and eventually dropout and delinquency [61]. Mayer and Leone [62] believe them to be ineffective and may actually increase school disorder. Skiba and Peterson [61] stated that relying on zero tolerance for school safety teaches that in order for there to be safe schools their rights and liberties will have to be suspended. This gives rise to troubled youths. Di Giulio [51] believed that rather than schools educating and teaching skills of socialization, they have adopted methods, which were more legal in nature. The student offender in his opinion received a sentence of expulsion or suspension from the school setting. He stated that when teachers carefully constructed a classroom environment which modeled respect and trust students would have a laboratory for learning to interact in a positive and safe environment.

He contends that punitive measures gave rise to violence as they only relocate the problems. Schools protected their image with a "get tough" policy. Aggressiveness required intervention rather than relocation. There should therefore be reconsideration of the dismissive, punitive measures. Like other studies he agreed that schools relied on after the fact remedies. There should be more education to foster prosocial behaviour in order to counteract antisocial behaviour. Most often disruptive behaviour was considered to be a problem of the individual. Instead the social environment or context of the conflict should be examined. An understanding of the conflict would inform more appropriate or effective intervention.

Ascher [21] was critical of the methods being used and referred to the schools as "fortresses." He thought that schools were more of a garrison type in which not many teachers felt at ease despite the concerns for safety. He stated that rather than offering reassurance, metal detectors, other mechanical devices, as well security forces were seen as providing a false sense of security. It was a symbol of failure to create safe schools. Sophisticated devices could not detect all the weapons entering a school, as it was not easy to secure every entrance to the school. The methods extracted a significant portion of the budget and served to increase rather than alleviate tensions in the schools. This was endorsed by Skiba and Peterson [61] who believed that although the measures may improve safety they impact negatively by creating an atmosphere of fear and intimidation.

Flannery [63] reported that some methods undertaken were short, "quick fix" methods or sophisticated multifaceted long term programs. Many were successful but some were not. Lack of success was due to the programmes being developed without evidence of the potential for their effectiveness. The evaluation of the program was crucial for assessment and improvement. Assessment should continue during the period when the program was being implemented. This would facilitate changes to accommodate new developments and improve outcomes.

Data from a study conducted by National Association of Social Workers (2001) revealed that students who gained knowledge and skills in resolving conflicts were able to apply the skills to conflict situation. They chose more assertive and less aggressive responses to situations after they had received conflict- resolution training. The programme was effective in reducing both overt and covert conflicts. Students resolved conflicts on their own by using the skills learnt. The social workers reported less referrals, or referrals requiring less conference time to resolve.

Smith and Sandhu [64] reported that most policies were seen as punitive rather than edifying. Most of the approaches were problem focussed in that they targeted negative behaviour as opposed to building alternative prosocial skills. In addition the majority of the strategies were reactive in the sense that they occurred in response to undesirable behaviour. The strategies instead should proactively operate to prevent the occurrence of such behaviour. A sense of connectedness between students, peers, family, school and community should be fostered. This would reduce the likelihood of students becoming engaged in negative and antisocial behaviours.

The measures, although sometimes effective, had negative effects. These included the placing of a significant financial burden on limited school funds, a reduction of time for classroom instruction and a decline in teacher and student morale [65]. Curwin and Mendler [66] were critical of the zero-tolerance policy being applied to every type of violent act. It was considered to be unfair as the same treatment could not be meted out to every problem. A denial of one's education for relatively minor reasons was viewed as a violation of one's rights in a democratic society.

Steinberg [48] stated that the main reasons for schools failure occurred outside the school and classroom. The ability of school to deal with the larger problem was limited because of the effects of larger social factors. Schools on a whole tended to disregard the contributing forces outside the boundaries of the school. The factors included parental disengagement from students' lives and their performance, activities, which competed with academic performance and exposure to a variety of risk factors. Stanley, Juhnke and Purkey [67] stated that violence programmes were defined to reduce violence without addressing school culture, academic achievement and existing student, parent and faculty concerns. The programmes appeared to treat symptoms instead of causes. Although it was possible to create a school where everyone felt safe it would be representative of a fortress rather than a school. Schools they believed should be both safe and conducive to academic success.

A prison-like atmosphere it was reported could create an atmosphere of apprehension and coercion. Instead programs should be proactive and preventative. The teaching of skills to mediate conflicts, such as peer mediation and conflict resolution proved to be useful. In an effort to increase safety and student success the use of group and individual counselling were advocated.

Casella [68] focussed on the use of zero tolerance policy in schools. He reported that zero tolerance policy attempted to prevent violence by punishing young people because of their potential for or display of violence. He further stated that the policy could create blockades for all students. It provided the addition of another risk factor to lives that were already overburdened with risk factors. Some students by the support they have may be able to manoeuver their way back to success after an expulsion or suspension. Not all students are afforded such privilege. Expulsion therefore, takes on different meaning when one student who is expelled can afford tutoring and another is not able to do so. The conclusion is that the consistent application of the policy does not mean that all students receive the same punishment. Schools needed well-developed discipline policy which should not only attempt to solve the problem of violence. Such policy should ensure that no student was "derailed" from his or her education or put in circumstances that increase the likelihood of criminality in the future. It was stated that a failing aspect of zero tolerance was that it steered youths from school property to various outplacements and sometimes into prisons. The policy was used to deal with mild offences it was never initially meant to address. Violence prevention and discipline policies should deal with the context of situations. The nature and history of conflicts, the relationship between those involved and the meaning that people make of situations are all part of that context. Students should be kept involved in school, be held accountable with the availability of a safe school. Help should be provided to students with the greatest difficulties. It is evident that use of suspensions or expulsions as a means of curtailing school violence. They do not achieve the desired result or solve the problem of violence. There was however, failure of the studies to show the perceptions of the students to being expelled or suspended. This is important, as some students prefer not to be in school. Students after returning from a suspension sometimes continue with the same type of antisocial behaviour as before.

Methodology

Introduction

The current study undertakes to examine violence in environment including the community and home and how it influences academic performance among a group of fourth and fifth graders from an urban area primary school. The purposes of the study are 1) To fulfill the requirements of a Doctor of Philosophy in Education degree majoring in leadership, and 2) To aid policy makers and administrators by providing empirical facts that can be useful in enhancing learning outcomes of pupils in violent prone schools. This chapter will give an overview of the research design, and the sample size used in the research. The chapter will also speak about the data collection procedures, limitations, a description of the instruments used, and how the data will be analyzed. Ethical consideration, validity and reliability are also components of this chapter. This study employs mixed methodology to carry out a research into violence and academic performance - positivism (i.e. survey research) and phenomenology.

Positivism and post-positivism

Historically, scientific inquiry was based on logic, precision, general principles, principles of verification, the standard of rigor, gradual development, "search for truth" and proofs. The proofs were critical to the pure sciences before the establishment of laws, principles, theories and apparatuses. Traditionally, science therefore, was guided by positivism. Positivism holds itself to (i) The collection of quantitative data, (ii) Separation of the researcher from the research process, (iii) Objectivity, (iv) Measurability, (v) Generalizability and (vi) Repetition. Thus, when the social science was born, the researchers embodied inquiries using the same approaches as the pure sciences. It follows that what was known about human behaviour had to be discovered through positivism and/or logical positivism. Social sciences like the natural sciences, was guided by logic (the study of valid forms of reasoning), metaphysics, the fundamental finds of things that really exist and the justification of knowledge (epistemology) which saw experimentative research been widely used to conduct inquiries. Science therefore was about the study of truth and not meanings. Why people do things, (i.e., meaning) was not important in research it was rather about the discovery of truth.

While empiricism is responsible for plethora of germane and critical discoveries that have aided humans' existence, it fails to explore potent things about people. Peoples' behaviours are not predictable, stationary, and while some generalizability exist therein, the 'whys' (meanings) are still unasked with the use of empirical inquiry (or objectivity and measurability). Qualitative inquiry mitigates against some of the inadequacies of objectivity, provides rich data on humans' experiences, and aids in a total understanding of people [27,69-72]. Thus, qualitative inquiry should not therefore be seen as an alternate paradigm to quantitative inquiry, but as a member of the understanding apparatus. This supports Schlick argument that we cannot know the truth without knowing the meaning (p.15).

Max Weber was the first to argue that an 'Interpretivism' approach can be employed in the examination of social phenomenon. Weber opined that why human behave the way they do is lost in quantitative methodologies (or positivism). He therefore, forwarded the use of subjectivity (feels, beliefs or meanings) in social inquiry. For years, the inquiry of social phenomenon was based on objectivity until Weber introduced an alternative paradigm. This gave rise to the emergence of (i) Ethnography, (ii) Phenomenology, (iii) Case study, (iv) Grounded theory, (v) feminism, (vi) Biography, (vii) Historical comparative analysis, and other methodologies (discourse analysis, heuristic inquiry, action research) were in keep with an alternative paradigm in scientific examination as approaches in understanding human behaviours.

Phenomenology

One scholar (Thomas Kuhn) argued that science not only embodies objectivity, logic, precision and general principles as humans are social beings [70]. As such, we must understand the meaning behind their behaviour which cannot be found by the use of objective methodologies. This gives rise to the use of subjective methodologies. One such subjective methodologies which is long established in the literature is ethnography [27,69,71-73].

Ethnography is one of the methodologies in qualitative research that evolved from revolution of science. It focuses on the everyday behaviour of people (their interactions, language, ritual) in order to determine inter alia, cultural norms, beliefs and social structures (Leedy and Ormrod, 138). It is the "naturalistic observations and holistic understandings of culture or subcultures" (Babbie, 282) or the "art and science of describing a group or culture" [40]. In ethnography, the researcher "adopts a cultural lens to interpret observed behaviour, ensuring that the behaviours are placed in a culturally relevant and meaningful context". Thus ethnography is concerned with the meaning and/or interpretation of groups within its natural settings.

Ethnography is wildly used by many scholars to examine different cultural happenings in a society or sub-groups: Chevannes [40] used this approach to determine socialization of males in the Caribbean; Gayle used ethnography to determine how adolescence survive in violent communities in St. Catherine; Levy [74] employed this methodology to examine how people survive in urban violent community; and Schlegel and Barry examined sex role differentiation and segregation. The methodology is also used extensively in studies of organizations and, in particular, to examine behavioural issues such as those of law enforcement officials. The examples here are Westmarland who examined "witnessing of illegal police violence" in Britain; Behr who explored "behaviour and the thinking of officers...possession of powers and their discretion for using it" and Haanstab, who examined order in the Thai Police Force. Organizations have culture and patterns of behaviour. And, as Silverman [27] notes, they are fertile field for the ethnographer.

The issue under investigation is also a phenomenon, and this requires a phenomenological methodology that will utilize case study as the method of analysis [26]. In keeping with the phenomenological methodology and case study method, narration will be used to present the information as well as theme identification.

Interviews-face-to-face

Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were chosen as they were closest to the unstructured interview which is flexible, iterative and continuous as well as more likely to yield information that were not planned for Semi-structured face-to-face interviews allow for systematic and consistency while giving sufficient latitude for the subject to 'digress' thus enabling a deeper probe [71] and facilitating new and unexpected information. The use of semi-structured (instead of structured) format study enabled the researcher to make deeper probe into the issue-An inquiry into the perceived effects of community and family violence on the academic functioning amongst a group of grade four students at a school in a violent prone community in Spanish Town, St. Catherine.

The face-to-face interviews took the form of a "guided conversation" where the interviewees were seen not as "passive conduit for retrieving information", but more for interpretation and perspective thus facilitating a deep probe. The interview schedule has various semi-structure questions for the study. The intended time for each face-to-face interview would be twenty-minutes.

Focus group

From a listing of prospective participants-students whom had returned their Consent Form to the office-the researcher arbitrarily selected fifteen students to meet with a discuss the issue of violence and its effect on their performance. The students were brought into an enclosed room with an external supervisor whose function was to ensure ethical standards and decorum was adhered to in the room. On average, the focus group discussion should last for 30 minutes. A tape recorder was monitored by an independent person. Another person was the note taker and this division of labour was done because the researcher wanted to ensure that all the information was obtained and that no one person was assigned to more than one task. The note taker will be carrying out a verbatim recording of the spoken words by each student.

Document reviews

The researcher reviewed written documents such as statistics, documents from the Ministry of Education and Culture, written relevant literature on violence and academic performance and newspaper articles. A major reason for the document review was to assist in triangulating [75] and validating information obtained in the interview, given that interviews "rarely constitute the sole source of data in research" [76].

Research design and sampling

The research design for the present work is an exploratory one in which the researcher team relied on subjective perspectives of participants and no objectivism will be employed. The research was conducted using a non probability approach - purposive and snow balling sampling approaches was used to ascertain the sample for interviews or focus group sessions. The population was chosen solely based on two criteria. These are 1) Attend a particular primary school in Spanish Town, St. Catherine; 2) Less than 12-years-old; and 3) Reside in a violent prone community. Thus, participants who fulfilled those criteria were part of the sample. There were eleven participants-four from grade 4 and five from grade 5.

The nature of this study is such that, the researcher chose participants based on their willingness to participate in the research process and them meeting the conditions for inclusion in the study in order to meet the general objective of the work-purposive sampling [77]. As such, participants who are not cognizant of the issues of this research could offer any assistance and therefore were not used [73]. Thus, fifteen (15) participants were either separately interviewed by the researcher or interviewed in a collective setting (i.e., focus group).

Having outlined to the various stakeholders-principal, vice principal and teachers-the researcher provided the classroom teachers with the requirements for selection (i.e., conditionality) and they then set up a meeting like that of a Town Hall setting. The researcher informed the students of the nature of the study, and they he seek their assistance in participation. However, they were informed that their participation or non-participation is totally based on a written consent from their parent, guardian, or custodial caregiver. A Consent Form was given to each student in a sealed envelope and they were asked to have them sign and returned on or before the next four weeks. The students were asked to give all signed Consent Form to a secretary in the Administrative Office.

Study setting

An urban government operated primary school is the target of this study. The school's population accounts for two thousand ranging from ages six to twelve years old. The grades that constitute the school's population are 1-to-6. The majority of students who attend the school are from poor socio-economic background and violence is a common occurrence on the school grounds. For this research, the participants were chosen from grade four. A quiet room was selected to conduct the research. This room was in close proximity to the guidance counselor's office. It was secluded and provided complete privacy, so as to create an environment where the children could feel safe in expressing themselves truthfully. As such, no teachers, administrators, and/or ancillary staff were invited or attended these for an in order to give the students an opportunity to openly express themselves with fear of reprisal from the school's personnel.

Pilot study

One of the philosophical assumption of knowledge is that one has is the solely holder of truth, wisdom, understanding and experience in this vast and complexed socio-physical world [26,77]. As such, requesting assistance from expert in the field; other authorities; and pilot testing instrument goes a far way in understanding the final quality of the items. Hence, the researcher consulted research books such as Basics of Quality Research by Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin [78]; Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches by John Creswell [77]. The Practice of Social Research 10th ed. By Earl Babbie [73], and Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 6th ed. By William Neuman [69] as they provided some conceptual and technical guide in research process, especially itemizing questions for an instrument. One of the recommendations by all of the aforementioned methodologists is piloting testing the actual instrument in order to ensure readability, understandability, validity of the items, and most of all does the items actually measure the intended research question. In within the recommendation of the scholars, I seek to comply with this in order to improve the quality of my research.

The instrument was tested on a few students at Northern Caribbean University who are unlikely to be selected in the final sample. Pilot testing was done to validate as well as to ensure reliability of the data gathering instrument. The instrument was piloted with fifteen respondents from a similar population that was not likely to be a part of the actual sample for the study. The exercise is estimated to last for thirty-to-forty five minutes. The respondents were coded and put into the computer. This was done to determine the validity, reliability and internal consistency of the items. Modifications were made to the initial instrument based on the feedback given by the supervisor/methodologist as well as the actual piloted respondents. The input was fed back into a modified instrument to formulate the final questions.

Data analysis

Three concurrent actions are pertinent in the analysis of qualitative data: Data reduction, data display and conclusions and verification [71]. In this research, an equal amount of raw data taken in note form as well as tape recordings was retrieved during the interviews. For the qualitative aspect of the study, the researcher utilized a thematic approach [26] in focusing, simplifying, transforming thus reducing the voluminous raw data into different themes (or social constructions). Having formulated a variety of themes, they were then used to shape the format of the presentation of findings (narrative, summative) which later informed conclusions and verifications. In cases where respondents were asked to rate a particular event, these were presented in a tabular form.

Method of analysis

The methods of data analysis were 1) Research questions, 2) Themes, and 3) Narrations. The researcher collected data from observation on naturally occurring behaviors in their usual context through the detailed record keeping of events, feelings and conversations of participants as well as their non-verbal communication expressions. Responses from the instruments were analyzed in order to develop percentage frequencies, charts and narrations.

Summative Model of Research

Table 1 below indicates the research questions and the methods used to gather information (Table 2).

Recording procedures

The researcher will employ a professional audio engineer. The audio engineer will institute a microphone system in the room. He will wire each participant with a small microphone that will be placed on their person. The microphone will transmit the spoken words in a system that records the information on a tape. The engineer will be seated at the back of the room, monitoring the quality of the audio and he will only interject in the discussion if the quality of the record falls below an acceptable level. On completion of the session, the audio engineer will remove the microphones from each participant, remove the equipment and machines from the room and supply the researcher with a tape of the recorded session with the participants in interview as well as the focus group discussion.

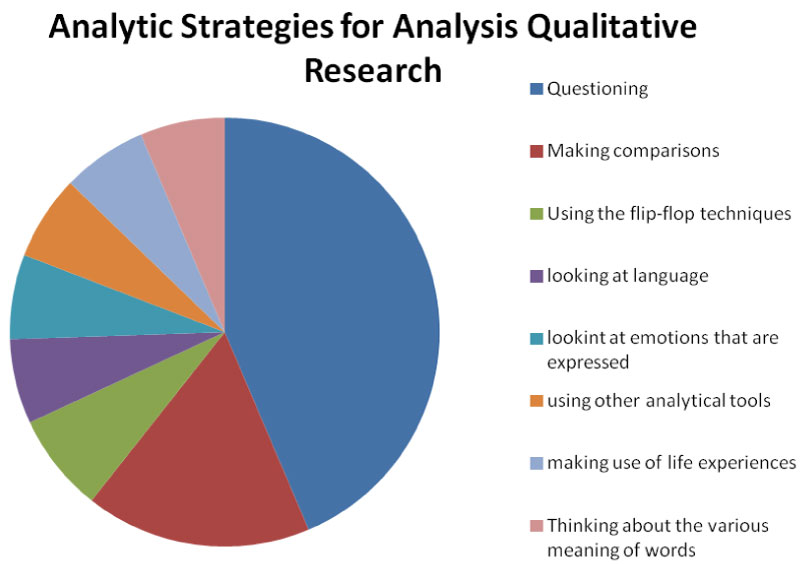

Descriptions of analytic strategies

Having reviewed and read Creswell [77]; Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. [78]; Dainty, et al. [79] Saldana [80] and other scholars, I have designed a graph that depicts some of the analytic strategies that are needed by the researcher prior to analysis qualitative data. The strategies are captured in Figure 2.