War or Religion in Different Cultural Contexts: Discerning War, Violence, Empires or Proselytizing & Religious Cults from Archaeology and Literature

Abstract

What is more important in the spread of civilization, military action or religious ideology? Trade and exchange are also significant and some historians like Braudel [1], have linked trading and raiding together and considered their effects. Here I compare the historical and archaeological evidence concerning the role of religion and war in civilization and how that evidence has been interpreted. Narratives that emphasize war have been given greater weight, but the spread of ideologies appears to have as quick results but perhaps had more enduring effects. The contemporary world is the product of colonial conquests furthered by conversion and suppression of aboriginal religions, yet today religion motivates considerable social instability across the globe. Migration from colonized areas to First World nations complicates this situation, as colonizing nations (e.g. France in Mali, Britain in Iraq) continue to act militarily. The roles of military action and religion in producing what Blackman [2] called political discipline for stability or resilience is of great interest.

The Central Andean site of Tiahuanaco (Tiwanaku) has been designated as the place of origin of a religious cult that spread within the development of a state, expansionist in nature and colonial, though pluralistic. The military nature of this state has been replaced in recent years by a theory of religious cult [3]. The nature of its spread is here paralleled with those of the Kuksu religious movement of Southwest and California Native American peoples as well as the Sanusi movement of North Africa in the Nineteenth century. Tiahuanaco is therefore interpreted as not a military expansion, but rather a spiritual transformation of existing states. This analysis is framed in the context of current theories of warrior cults in archaeological narratives and the nature and style of archaeological reports. Humans are certainly susceptible to ideas and to violence, but in our own time, conversion to philosophical and religious ways of life is a powerful motivation for change as is lifestyle which we have seen in the past fifty years transform the world by global images of modernity. This contrast, war or conversion provides an interesting test of change in the ancient world.

Keywords

Tiahuanaco, Kuksu, Sanusi, War, Religion, Proselytizing, Culture change, Interpretation, Literature

Introduction

The nature of the archaeological report has been characterized as a reflection of Twentieth century military narratives [4]. Here that theory is tested from the results of an earlier formal analysis of archaeological reports [5] and by contrasting the military narrative with a religious one. As important is the effect of contact on culture and social organization. Redfield [6] describes the effect of innovation and discovery in small scale societies, but the dramatic contrast of complex societies on those less populous or organized in more heterarchical form or less complex institution has been tremendous as evidenced by the many examples of European colonialism. How ideas spread and how they effect different societies and cultures with varied histories and cosmologies, is of central interest here.

The Central Andean site of Tiahuanaco (Tiwanaku) has been designated as the place of origin of a religious cult that spread within the development of a state, expansionist in nature and colonial, though pluralistic. The military nature of this state has been replaced in recent years by a theory of religious cult [3]. The nature of its spread is here paralleled with those of the Kuksu religious movement of Southwest and California Native American peoples as well as the Sanusi movement of North Africa in the Nineteenth century. Tiahuanaco is therefore interpreted as not a military expansion, but rather a spiritual transformation of existing states. This analysis is framed in the context of current theories of warrior cults in archaeological narratives and the nature and style of archaeological reports. Humans are certainly susceptible to ideas and to violence, but in our own time, conversion to philosophical and religious ways of life is a powerful motivation for change as is lifestyle which we have seen in the past fifty years transform the world by global images of modernity. This contrast, war or conversion provides an interesting test of change in the ancient world, and is the subject of our discuss of three movements or changes in social meaning and behavior in different times, one pre-historic in the Andes, one during the conquest of Native Americans in North America and the third, in North Africa primarily among the Bedouin.

The remains of a civilization in Bolivia & Peru known today as the Tiahuanaco Empire, after suggestions by Uhle [7], has long interested students of civilization in the Americas. It had no written history to guide modern scholars, its creators left only monuments and a unique culture, termed the Tiahuanaco Cult [8]. In the west the problem of authenticity of materials is difficult due to the fragmentary nature of the remains of manuscripts, errors and additions in copies [9,10]. The fact that this cult appears suddenly and spreads over already existing political entities with local traditions has led scholars to assume that it was both a military and religious cult. Some have interpreted this spread as that of military colonies and empire [11]. But cult symbols, as icons or images of natural objects and art can have diverse roles in the ideology of a society as in the "images not made of hands" related to the Shroud of Turin and similar objects [12].

A central problem with attributing cultural changes to military aggression without historical references is that military aggression is a general concept within a broad reference to conflict between human groups. Historical examples show that military expansion can have minor effects on local religion, as in the Roman case, or drastic effects as in the European case in the Americas. Caldararo has addressed this problem elsewhere [13], as war is nearly as often an excuse to describe cultural change in the past, as is religion without ample justification as to what "war" means [14,15]. One might consider the military expansion of European populations in the Fifteenth century to result from cults of Christianity formed in the crisis of Europe following the Black Plague. Or a similar case could be made for the spread of Islam after the Seventh century of the present era. The central difficulty, as Lewis Binford [16] has noted is "... how to create evidence from observations". Sometimes our evidence may have been contaminated by historical accident. For example, when we read that the Spanish claims of Aztec and Mayan human sacrifice functioned in part to brand their cultures as savages and deserving of destruction. A definition of human sacrifice is also needed, one that is not culture bound (ancestor worship aside see Caldararo, [17]). Vaillant [18] quotes all European sources (Duran, Torquemada, the half Spanish Ixtlilxohitl, Bancroft and the Codex Telleriano -Remensis - printed on European paper) for the supposed Aztec and Mayan custom of ripping the heart out of victims. Many other examples of such iconic illustrations and their interpretation can be found in Boone [19]. But this idea was commonly attributed to the Irish by the English in the time of Richard II and appears in Froissart's Chronicles [20] as a vehicle to demonstrate how savage and barbaric the Irish were with the added relish of describing how the Irish were supposed to have eaten the hearts of victims. The fact that Foissart's work was written over one hundred years before the Spanish tell the same tale about the Aztec and Maya might lead one to suspect that it was a recycled means of producing the same idea of savagery for the Native Americans. European clerical scholars had access to Froissart's Chronicles for one hundred years before Columbus sailed to the Americas. It is likely they had read or heard of the "savage" Irish; did they manufacture the story of Aztec and Mayan "heart wrenching?" There is considerable debate on the authenticity of this practice among Native Americans before the conquest [19,21]. We lack evidence in terms of bodies, trauma on the rib cage and the numbers of cases that would justify the claimed frequency of the practice. The same is true of cannibalism that has been claimed for Native Americans, especially the Aztec. For example, Tringham [21] noted that descriptions of Aztec sacrifices were remarkably similar to those described by Herodotus for the Scythians, did the Spanish simply copy these "barbarous" practices for the Aztec as readymade badges of those who required European civilization? Where are the remains of the sacrifices? There was an advantage in doing so as Ferguson [22] notes, once a tribe had been designated as cannibals, Spanish law held that anyone could capture its members and force them into slavery.

In archaeological research the problem is magnified as in cases where we have evidence of mass violence in prehistory as at the Talheim Death Pit, or the mass burial at Schletz-Asparn or the Crow Creek site. Usually explanations start at the most basic: Violence for food, women or territory, but exclude ideological violence (as, for example, the Jim Jones massacre at Jonestown or those recently by ISIL/ISIS, see Caldararo [23]) as we seldom impute contemporary classes of behavior to people in the past. What would be of value is knowing if there is a scientific way of answering these questions? Is there a quantifiable group of elements that defines a battlefield, one from the Neolithic, the Bronze Age, Iron Age? Are these elements universal or are they significantly modified by culture? Certainly not all examples are as clear as that reported from the Bronze Age site at Tollense River [24] and we should expect more to be discovered if we can believe the ethnohistorical sources as in Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars.

Ossuaries are often of religious origin, as at St. Mary's Church of Wamba, sometimes of military origin as memorials, as at Gallipoli where we find 3,000 French unidentified soldiers buried together (https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/history/conflicts/gallipoli-and-anzacs/locations/explore-southern-warcemeteries/french-war-cemetery). Others, as those in Malta from the Neolithic are likely kin-based burials, or those of Native America [25]. To differentiate the events that lead up to a single large burial of humans from war, to identify the massacre of dissidents in an ancient context, or of heretics or a mass sacrifice [26] seems to produce some degree of complication when we note the massacre of the citizens of Srebrenica during the Yugoslav civil war [27].

This does bring up the quality and purpose of any recording of contemporary events. In Wilkerson's [28] review of the literature of the conquest he quotes a number of sources, mainly Christian priests or converts with priests, describing decapitations. One wonders what the value was of this, was it like the descriptions of the "savage" Irish, to demean them and justify the brutality and slavery that followed? It also seems much like the tradition already well established of accusations against pagans or heretics in Europe which resulted in their torture, fine, murder and confiscation of property. This is paralleled by anti-communist regimes as in Chile where even the children are stolen from victims charged with being communists and rebels [29,30]. Also, at the same time Wilkerson's padres were discovering pagans in New Spain and executing them, there was a wave of witch hunts and executions in Europe [31] from 1560 to 1630. So the padres were only finding abroad what their equals were "discovering" at home. And a whole science developed to root out, identify and exterminate demons, devils, rebels, sexual deviants, ill and insane and heretics [32].

The Irish example brings up the antiquarian controversy over Roman claims of Druid human sacrifice [33,34]. While the usually tolerant Romans described the sacrifices as savage and numerous, questions have been raised over the past 2,000 years over the actual number or reality. Recent archaeological finds and reinterpretation have begun to lift these concerns and give a picture of Druid human sacrifice that parallels Roman reports [35]. Nevertheless, the Roman descriptions often seem similar to those reported by the Spanish of Mesoamericans, raising questions as to the authenticity of the Spanish reports as transferred information from European accounts.

Interpreting War, Sport and Violence

Pijoan and Lory [36] have summarized the materials found in various Mesoamerican sites that can be attributed to violence or at least the manipulation of the dead body before burial. Most of these remains are found at or near what are considered to be ceremonial sites at least up to the Post Classic period. The numbers of burials included in each site are small and could hardly be considered evidence of warfare. After the Post Classic, sites with masses of bones that had been damaged in a variety of ways appear at different locations and these finds have been considered to be the result of cannibalism, though the numbers are still relatively small, 10 to 18 individuals is the estimate. An ossuary found during the excavations of the prehispanic city of Tlatelolco reportedly held 140 individuals. These differed from the other two given they appeared to be interned in an orderly fashion. Villa, et al. [37] and Tim White [38] have made attempts to combine analysis of human and animal bone processed in pre-Columbian context at Mancos that provides direct comparison of techniques for each, but again lacks ethnohistorical context to interpret the materials. Villa [39] notes that reports of cannibalism have often been false and related to insults and politically motivated justifications of violence against minorities, so we must be careful when applying such behavior to people (Figure 1).

Pijoan and Lory [36] examine a number of factors and to determine the difference between what finds can be identified as cannibalism and those human sacrifice, although the consumption of sacrifices by those involved in religious ceremonies is not unknown and in many locations is typical [40]. The idea of ritual processing of the body as in the case of the example of Tibetans where the bones are thoroughly defleshed, [41,42] was not considered as an alternative explanation, or examples of the dismemberment of shaman and the ritual cleaning of the bones and their construction into ceremonial materials [40]. It is true that some of these ceremonies, as in Melanesia [43], include complex rituals, some including ceremonial consumption of bodies, though most of these reports depend on missionary records at a time when local religions were being sanctioned. Though reports exist from sailors and other visitors [44], the variety of original context of reports is surprising as is contemporary discussion [45]. Burials in the Mayan area also are difficult to interpret, the Maya reopened tombs and they manipulated skeletal parts to "...an unusual degree" and used as ritual elements, trophies and ancestor rites [46]. Ossuaries and pre-historic cemeteries present problems for interpretation where they appear without ethnohistorical documentation, but comparison between those with such informative materials and those without can provide some guidelines [25,47]. In some cases the ideology created by Western scholars for the Maya has limited the possible alternatives, as in the case of decapitation, for example, at Tikal where an elaborate system of nobles and kings in a panorama of ritualistic warfare defines the burials in special chambers [48]. The opportunity for a different interpretation is lost when Burial 85 is discovered, where a headless corpse is found. The ideology of the Ball Game Cult is addressed to explain the condition: a king had lost a contest in the ritual warfare and was then buried without his head which became a trophy in the style of the way the two twins of the supposed Mayan myth related in the Popol Vuh (a post-conquest document "found" by researchers in the possession of a Mestizo family, see Tedlock [49]). We might recognize what Gates [50] stated of Landa's memior, that most of what we know of the Maya is taken from their conquerors' views. An alternative interpretation, using the same ideology, but instead of focusing on war, if we rather look on the ritualized game which is argued to reproduce certain indigenous religious ideas of the movements of the planets, a different solution can be constructed with as much authenticity. The burial can represent an athlete who lost a game and therefore lost his/her head. Headless corpses are not unusual either; depending on our knowledge of burials we can find examples among the Kenta Semang [40]. The same is true of the interpretation of "kings" standing over "victims" or "captives" in Mayan images as in the case of the Bonampak Murals and others in Mesoamerica [48]. The central planet, and the "war complex" [48] have focused on has many similarities with the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar and the rising of Venus (Ishtar) is often associated with her intercession in war [51,52]. The parallel seems to be another remarkable coincidence. However, the interpretation of Schele and Freidel [48] and most post WWII archaeologists concerning the Maya has changed drastically from that view held before the War. Given in Bishop Landa's words, [50] the Mayans of his time related a prehistory of peaceful priest kings and this view survived 400 years. But the tale of the peaceful Maya and a revolt when the last king left was branded as myth and replaced with a narrative of warrior kings much like European history [48]. Schele and Freidel's book, A Forest of Kings, reads like a number of similar stories devised to give legitimacy to kings, emperors and tryants of all sorts. See the Sargon legend for an early example, origin of the pretender linked to the royal house via a mother finding an infant in a basket floating in a stream which is similar to one of the Romulus and Remus stories [52,53] and Mosas [54]. One can see a parallel in the history Tibetan priest kings told supposedly to British colonialists after they had driven the Chinese out in 1903. This view is contradicted by the only non-European visitor to have left a history of his visit. This was Japanese Buddist student Kawaguchi [41] who finds the Tibetan monks unruly, brutal, filthy and exploitive of the population. One can easily criticize the British version of Tibet as being a justification for their colonial intersts and aggression against the Chinese [55].

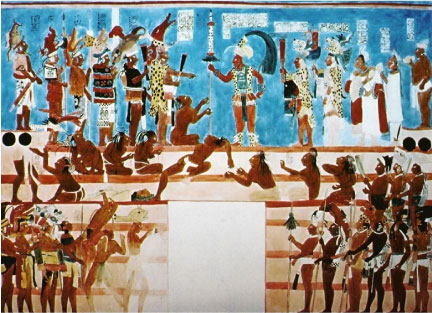

What is the meaning of the Bonampak murals? They have been interpreted as sacrifice, but are there other explanations (e.g., medical) or are they even depictions of events? If we compare Bonampak with the depiction of Charles V's victory over the Schmalkaldic League after the battle of Muhlberg in 1547 [56] (about the same time as the conquest of the Maya) we find a fantastic portrait of Charles V seated over his defeated enemies, chained to his feet like dogs in 1547 (Figure 2). This never happened, yet its depiction is a powerful representation of how Europeans saw power displayed.

Consistent types of violence can produce uniform patterns of injury as Walker [57] has noted and systematic violence associated with caste and class has been demonstrated in examination of African American cemeteries [58] and such violence has been documented in other cases as in the Indian caste system [59,60]. Regarding headless corpses Kwang-chih Chang [61] notes burials of this type at Erh-li-t'ou along with some that appear to have evidence of the arms tied behind the back. These appear in what is described as the non-elite burials and so perhaps also consistent with caste violence.

Kolata [62,63] reassessed the archaeology of the Tiahuanaco culture and reaffirmed the idea of a violent process of conquest and impression of a dominant system of architecture and religious symbols over subject peoples. With little to go on than enigmatic sculpture, some scholars have created entire ideologies for the Tiahuanaco empire [64]. Some scholars could not imagine how a cult could spread as fast and replace local traditions as quickly as the Tiahuanaco cult did [8]. This idea of a relatively fast expansion has been questioned in recent years [65]. Can the spread of a cult be similar to that of military conquest? In Millon's [66] comprehensive survey of the archaeology of Teotihuacan, we find a more complex situation, describing a very successful social and economic system. The nearly 800 year span from origins to collapse are impressive as is the ability of this system to maintain order with a population that reached some 250,000 at times. Explaining its origins and demise has become as difficult as finding causes of the fall of the Roman Empire (compare Rostovtzeff [67] with Beard [53]). The evidence of cultural pluralism is convincing, as is the needed cooperation of people or ideological or physical control to produce and maintain the massive building program and functional maintenance of the city and its widespread economic and governmental influence and power. It is difficult to interpret the specialized headdresses as military as they could as well be religious and relate to trade status [66]. This is supported by the "merchant's barrios" found over central Mexico as well as the unarmed individuals at Monte Alban meeting "officials" in typical Zapotec headdress. But Teotihuacan's end is described by many as cataclysmic, more devastating than a collapse. Some argue that this was due to a loss of control of trade networks, but do not provide an explanation or model for why it was so quick and complete (Sanders, et al. [68]; see also Tainter [69]) while Millon [70] suggested invaders but by 1988 is less convinced due to a lack of evidence. Instead he points to the "build up of internal tensions" and a widening inequality, but notes that the city had been able to deal effectively twice in its history with economic and social crises and he falls back on Robert Adams' vague idea of a loss of resilience as the final cause [71]. Perhaps today, this has more force than in 1988, when strangely enough an example of the loss of ideological power in social glue resulted in the collapse of the Soviet Union, even though that collapse was not "catalysmic" but only "catastrophic." A recent assessment supports the idea of a long decline in conditions, both economic and social likely related to growing inequality which sapped the traditional ability of its "resilience." This same assessment [72] reports on considerable and compelling evidence of long traditions of cultural pluralism that might explain and support the idea of a comprehensive ideology able to meld people of different culture histories together. While Cahokia shows less diversity of people, the nature of the city and its expanded population outside of the central core and into the hinder lands suggests either a magnet of trade or of ideology [73].

Toynbee [74] has shown that religious ideas have parallel time periods of spread, as do military conquests. Crapo [75] defines cults as new religious movements; Morris [76] refers to them as redefinitions of religious dogma. Religious cults can produce colonies to survive repression, to spread their ideas [77] or preserve them [78]. However, we do have examples of cults in the Americas and elsewhere spreading quickly and producing economic, political and religious change. One example is in California with the Kuksu religion [79,80], the other is the Sanusi cult of North Africa [81].

Bruhns [7], noting the elaborate structures and concern for detail, especially the Akapana, and the variety and innovative nature of the iconography, suggested that the spread of the cult may have been the result of an organized missionary enterprise or revitalization movement. When seen in the context of the strontium isotope data interpreted by Knudson [82] the movement of individuals native to the Tiwanaku heartland undermines the idea of a military conquest and supports ideas of the spread of a cult or movement of a few missionaries and this opens up some interesting possibilities to concepts of war or religion as explanations.

Sources and Interpretation

The iconography of New World civilizations has largely been interpreted from the background and context of the Christian West or Christianized natives or sons, legal or not of Spanish colonists [83]. This would be like the efforts of a converso in Spain writing a history of the Jewish religion in 1500, his efforts might be seen as evidence of guilt and he then be subject to the Inquisition. Forbes [84] addressed this issue with regard to colonial Native American literature. There might be some original value in trying to interpret the residue, but imagine attempting to recreate the philosophy of the Enlightenment from a Catholic Church missal. For people like de la Vega, sons of conquerors and native women, the end could be justification of the ancient culture (as some have seen in Jomo Kenyatta's Facing Mt. Kenya [85] see also Berman [86]). For others in this situation it can be seen as a validation of the justice of the conquest, and we cannot underestimate the intent of the padres to undermine the memory of civilization among Native Americans as it was a means to ensuring their subjugation. Using these sources some students have attempted to apply a comparative approach with existing legends and traditions of local peoples as in the case of Dennis Tedlock's Popol Vuh [87] or Schele and Freidel"s A Forest of Kings [48]. Nevertheless, these are valuable efforts to understand the worldview of Native Americans at the time of the Conquest. Interesting in this endeavor is the opposite process, the Native American interpretation of European literacy examined by Wogan [88]. But there is also a school of thought that argues for cultural memories retained in trained specialists who can produce faithful renditions over long periods of time [89] and the nature of oral traditions has been given considerable attention by Goody [90]. Nevertheless, some have produced significant challenges to this idea [91]. Problems of literacy are significant today, especially as regards rote learning [92].

Radin's critical efforts to produce a methodology of ethnohistorical analysis have been largely ignored [10] as has that of Dark [93]. Caldararo has detailed some of these problems in earlier publications [13,94]. The difficulty in arriving at an authentic interpretation has been detailed by Tedlock [87] and later in a more extensive forum by Evers and Toelken [95].

Even our ability to understand the literature of more closely related civilizations to ourselves than those of Native America demonstrates this problem. As Thomas Babington Macaulay described in his Lays of Ancient Rome [96], the Latin literature of the Romans that flourished before the Punic wars was so obliterated by the fashion of Greek literature that by the time of Cicero it was unknown. The same is true of European folktales and their originality as Alexander H. Krappe shows [89]. And Lord Raglan [97] heaped scorn on the tales that had been routinely incorporated into history in the 19th and early 20th century by scholars.

While the validity of the interpretations is certainly questionable, there is doubt that most sources derived from the Conquistadors are of any useful value other than noting the competition of the Spanish actors in establishing their claims to land (Native Americans were "savages" like the Irish were considered by the English), money or position as Peter Martyr D' Anghiera documented [98]. Such embellishments of their experiences and drawing on Classical models for their adventures are exemplified best by Camoens' The Lusiads. But then other means have been generally lacking or not considered useful. Boas' [99] neutral approach does not provide the kind of rich imagery that students of Native American societies expect. Perhaps the conclusion of Craine and Reindorp [100] goes too far in arguing that the work of the Spanish copyists made the "saved traditions," especially of the Books of Chilam Balam, "nonsense." Certainly these were not the usually small, but often meaningful omissions or "corrections" Clark [9] describes for copyists both at that time and in antiquity. Mignolo [101] addresses this problem in the origins of European attempts to understand the "Other" and the invention of comparative ethnology which a number of scholars place in the Enlightenment (e.g., Pagden [102], Amselle [103], see summary in Manganaro [104]; Marcus [105]; Marcus and Fisher [106]; Strathern [107,108]). Most of these critiques of early anthropology, like Strathern, repeat the use of travelers' and especially missionaries' contact with indigenous peoples and the efforts of the writers, including Lubbock and Frazer, to try and make some sense of the reports as a reflection of mankind as a whole. Amselle [103] takes a wider view of postmodernism and post-colonial studies and attempts to form a means of creating a more realistic and less ethnocentric approach. Stocking (especially his 1983 book) was a master of this picking out choice examples of reports that seemed to disparage native perceptions and intelligence, revealing, as it were, the anthropologist's bias. Reportage can be biased by many factors, just as one is dumbfounded when confronted by a hysterical citizen of England spouting jargon about Brexit. The individual might be under the influence, angry from some other encounter or just ideologically possessed. Although reporting on it can be accepted as a fact, especially if recorded on a smartphone. Bias can be countered by comparison of a variety of views of the same phenomenon. The nature of gender roles and authority in pre-industrial society has been balanced by such reanalysis (e.g., Leacock [109]). Therefore, Mignolo's project could have promise if sufficient materials are available and broadly compared.

Yet efforts by people of any society to rationalize contact and to explain differences in strangers or new people are not simply an element of complex societies and not new to modernity. Often Herodotus is singled out as the first ethnographer, but we see similar efforts in Asia with visitors of various kinds [110] and the Middle East (e.g., El Mas'udi). And though Sahagun reports of "spy traders" for the Aztec, and trade allowed for a flow of information among the Maya and their neighbors, the reports of traders can have a variety of uses [111]. It can explain custom as well as define differences and allow for alliance and economic as well as political intercourse. Criticism of early western anthropology has been largely dogmatic and lacked both context and background [112].

Padden [113] is skeptical, considering the idea of distortions and inventions of some of the codices by Spanish writers, but is not balanced in his general acceptance of most. Morgan [114] was an early skeptic of Spanish reports and points out obvious fabrications. The motive of making the native of America appear as the devil worshipers the padres believed them to be, certainly fell in with the pattern of treatment of the literature of Moorish Spain during the Reconquista and after [115]. But we can see other motives and methods in action here, as Anghiera noted, most of the stories of the conquest are suspect, even some of the most famous, like Cortez and the Malinche seems too close to that of Classical efforts to unite a conquered people and the new rulers, as early as in Alexander and Roxanne (Metz Epitome see https://web.archive.org/web/20070929194052/http://www.alexander-sources.org/). The drunken brawling and violent misogynistic images of supposed Native Americans like those in the PopolVuh [49,116], bear a suspicious similarity to works by hedonistic monks and priests of the time in Europe (e.g., Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel )[117].

While almost all the post-contact documents were produced in the context of Christian overseers, a few were claimed to have been the result of interviews with "ancient ones" often claimed royal relatives. This includes the Royal Commentaries of Garcilaso de la Vega [83] who was born a decade after the conquest. His work contains many parallels with other works of post-conquest histories, as in the prediction of the arrival of the Spanish by a King Huaina Capac. Most appear to be attempts to create political identities and rights in the face of Spanish confiscation of lands [49,50,118]. Chimalpain's efforts are of this kind, e.g., his Diferentes historias originales. Though he also recorded the 1610 and 1614 visits of Japanese delegates to New Spain. One unique history is that by Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxchitl [119,120]. He produced an alternative source to Spanish interpretation of Mesoamerican history in some views, but his way of writing and conceptualizing that history broke with both the Spanish schemes for the New World and its relation to the old and other native histories but not the trend of establishing rights in the others, e.g., the mapas, lienzos. His "native archive" played a role in the development of Mexican nationalism and its relation to indigenous cultures. The fact that he was seen more as a castizo (Spanish/Mestizo) than as a native is a part of his problem in presentation, given that he was less than fluent in Nahuatl [119]. How much was history and how much imagined as an opposition to Spanish cultural and political domination is unclear [120].

Much of what is considered information about native writing is derived from the colonial context. For example, Mignolo [121] reproduces a supposed record of a meeting between twelve Franciscans and representatives of the Mexica nobility discoursing over the nature of native books. The attitude of respect present in this recreation by Sahagun contrasts sharply with almost all other descriptions of colonial attitudes toward native abilities as found in Las Casas or d'Anghiera [122]. Absent from Mignolo's discussion is the recognition that any such meeting was one of conqueror vs conquered and was most certainly an example of the Inquisition.

Mignolo [121] attempts to create a typology of the "book" that can be used to compare devices for "reading" information from one generation or practitioner to another. He is inspired in this by the work of the 16th century scholar Alejo Venegas, whose book, "First Part of the Differences of Books there are in the Universe," desired to incorporate all the forms of book, from scrolls to the forms of codex known in his time. Mignolo concentrates his approach on the codex and reading in the 16th century as a vehicle to study reading in Mesoamerica. While this is a laudable project it is ethnocentric as it limits objects in time and space and form. Cuneiform writing on tablets from the Middle East is excluded, for example. But in another work [101] Mignolo goes deeper into the nature and relevance of the book in the context of Europe in the 16th Century and Venegas' work place a central role in his analysis. He asserts that some European languages, due to their integration of literature and scientific thinking (as in the claim that Decartes joined literacy with numeracy, a rather dubious division given the Arabic scientists use of math earlier) gave rise to a unique and powerful form of linguistic use. But Mignolo [101] takes on, as other scholars of modernity have, the charge of addressing the vocality of languages and authority lost in the colonial adventure. He argues that, "Inscribing the languages of the early colonial period (Spanish, Portuguese, Quechua, Aymara, Nahualt) into the theoretical languages of modernity is a first step toward intellectual decolonization and a denial of the denial of the coeval ness...". This is a laudable goal, but with the literature destroyed and the pre-colonial context largely erased, one wonders if it could be done even by survivors (i.e., Maya of today, though mainly products of European education and culture. Even the appearance and transformation of pre-colonial Mayan institutions in the brief uprisings in Yucatan were heavily influenced by European oppression [123]. More depressing is the fact of substantial difficulties in reconstructing meaning, context and performance in languages that were vibrant and fairly isolated in recent times [124]. Goody's [90] studies of oral literature also leaves a dismal assessment of authenticity. One can expect the kinds of "reconstructions" produced by Schele and Freidel [48] that are either pastiches of memory and linguistic archaeology informed by archaeological anthropology, or are European adventures in graveyards of fragments.

This brings us back to Venegas and to other attempts of construct typologies of knowledge at the time (e.g., Martire d'Anghiera; Leo Africanus and [earlier] Ibn Khaldun). The types of books that are created and what they possess for humans is a concern for Venegas, though he was many informed of European books of the time. Also the idea of reading is imputed to Spanish sources for the Mesoamericans, they cannot speak for themselves on how to read, we have no independent documents of the pre-Columbian world that can inform us of their "reading." This is true also of Xxtlilxchitl, where the role of reading in life is subvervient to the creation of a rationale for native history and identity. Still, reading in Mignolo's approach is comprehensively discussed in a cross-cultural framework, even given how one-sided are the voices. Reading, however, even today is different from reading comprehension and the levels of literacy today are significant. Ideas about the level of literacy in the ancient world have varied. DiRenzi [125] argues that they were very high during the Roman Empire. The function of a reading device, a mechanism for transmitting information in time and space is determined in part by the complexity and conception of need in a society. Boas [99] describes the comprehension of the signs of animals and figures in Northwest Coast Native American "art." The people could "read" the designs to retell stories associated with their legends. In the same way many people have used message sticks to communicate specific details of daily life, e.g., if they are hungry, when they last found food, what direction they are moving in, how many are present, etc. These mechanisms and their use function within the needs of the society's complexity and are the foundations of other more developed systems of meaning from pictographs to alphabets as Kramer has shown for cuneiform [126]. How much is read on a daily basis and what its function is in daily life is a central point, but the form of such devices is not essential to the process. In this I disagree with Goody [127] who finds the form of the book, like Mignolo, to be of greatest significance as a sign of a literary tradition and its use in a culture structured by literary power. I find this to be unconvincing. If the proof of civilization is complex society as I have argued elsewhere [129], then Mesoamerican societies and those of the Andes were civilizations. Using a book, a quipu or memory, is a means to the end of organizing people and motivating them in concert and is but a process we call domestication.. Then as opposed to views like Goody [90], it is not the alphabet that created the social conditions for civilization, but many improvements in the process of human domestication, increasing the efficiency in producing a comprehensive human social environment [147].

However, some interpretations and the use of ethnohistorical documents have produced results that appear entirely reasonable [126,130]. Though such attempts are not without concerns [131]. Whether because this is due to their limited scope and physical references rather than broad generalizations associated with interpretations concerning subjective ideas like religion, is debatable. Even eye witness reports are unreliable and subject to a variety of interpretations and reconstruction [130]. Nevertheless, a wide range of variations to a new Direct Historical Method have been attempted and a selection of this diversity of sources was published by Boone and Mignolo in 1994 [132]. Schele & Freidel [48] argue a cultural identity between the villages of the Yucatan today and those of the distant pre-contact past, claiming that rites practiced today are the same as those of the ancient Maya of pre-contact times. One has to recognize that in essence this approach goes back to the origins of anthropology were the issue of survivals was a central problem in theory development [133].

With the foregoing caveat, I consider interpretations of the surviving images of the Tiahuanaco sculpture to be questionable at best (see for example, Millon [134,135]). As Francis Hsu [136] suggested, we must be careful with interpretations, especially religious symbols. He notes that if a person unfamiliar with Christian iconography and history walked into a Christian church and viewed the sculpture of Christ nailed to a cross above the altar, he or she might be compelled to interpret this grisly image as the worship of death in human sacrifice. My approach, like that of Tedlock and Schele and Freidel, is a modified version of the Direct Historical Method, described by Hole, and Heizer [137]. They call it the Direct Historical Approach, which bases interpretations of archaeological artifacts or other evidence, on ethnographic analogy. This differs from the original form of this kind of inquiry, the "Theory of Perizonius" which was an early version of the direct historical method ([138]; see also the method of W. Robertson Smith [139]).

As MacCauley [96] pointed out, Perizonius (1626-1672) first argued that the early histories of Rome were derived from the ballads of country folk after the obliteration of the original Latin literature, by both the sack of Rome by the Gauls and its extermination at the hands of fashion by the adoption of Greek literature and themes. Neibhur took up this idea in lectures at the beginning of the Nineteenth century [138]. In like manner, Tedlock [49,87] and Schele and Freiden [48] have followed this avenue of reconstruction, using scattered engravings on monuments, folk tales and the translated memories of later generations. Their assumptions have also introduced lines of argument that validate some rumor of conquest as when Schele & Freidel [48] assume from the post-conquest reports that literacy was minimal among the Native American civilizations. This sparked a debate over sources, reviewed by Houston & Stuart [140] that called this idea into question, which involved tapping resources from ancient Mesopotamia and China.

Kuksu and the Ghost Dance

Kroeber [79], using ethnohistorical sources, reports that in some areas in the Western United States traits associated with the Kuksu religion were spread by the Ghost Dance. The term "Kuksu" refers to a culture hero. There was also evidence that Kuksu elements, and perhaps the cult was derived from the Southwest Pueblos [141]. So we have here the example of a religious element of one religion transferred into new areas, not by conquest but by a new spiritual movement. See Bettinger [80] for a more recent analsysi. This affected behavior as diverse as architecture (e.g., organization of the sweat house) and musical instruments (e.g., the presence of the drum in California) and the performance of roles as in the clown, moki or Kuksu rather than priest for some ceremonies. Also dances and certain kinds of social organization were transferred as, for example, in secret societies [142,143]. And we find evidence of long distance trade and association among other Native American civilizations.

This idea is not entirely supported by all the evidence, as the figure of different actors shown in Loeb [144,145] and Jones [142] see also Bettinger [80] who cites other examples of the transfer of Pueblo ceremonial objects to other peoples and demonstrates that there is evidence of contact with similar masked actors among groups between the Pueblos and California, including the Cochimi of Southern California. Kuksu as Raven in the creation cycle of many California Native groups, is seen in, oral literature collected by a number of researchers and sources, as the counterpart to Condor. He appears among the Maidu, Pomo, Wintu and Miwok as also Raven [146]. There is some evidence that the cult involved males from different tribes to form relationships that allowed or promoted trade and peaceful association and described as secret societies [111], and is similar to the origins of banking and finance in Europe [128]. And we find evidence of long distance trade and associations among other Native American societies [111]. This appears to have been complicated among the Aztec as some reports assert traders acted as spies for their military adventures [111], but I think this has always been a role for traders. The idea of a massive population at Teotihuacan attracted by successful food production (food sharing as in other complex animal concentrations, see [147]) and trade is largely missing from most discussions of the rise of this city. The effect of regular food supplies and an ideology of order would provide a powerful basis for stability. Complicating the spread of the Kuksu rites and dance materials is the fact that it was largely a post-contact phenomenon, and in some aspects could be considered a revitalization movement, as it appeared as a world renewal rite in some contexts [143,144]. The Kuksu dance of the Central Sierra Miwok appears to have been introduced to the Southern Maidu from the Pleasanton peoples (Bay Miwok and Costanoan) according to Gifford [148,149]. His "secret society members" section includes a description of E.M. Loeb's 1925 investigation of the Clear Lake Pomo's practice of the Kuksu religion. Some differences of opinion exist over the origins and diffusion of the cult [150]. The dances were witnessed by a number of non-Native Americans in various locations, especially among the Pomo [143,144] from 1892 to 1904. The frequent association with the sweat lodge and healing among a number of other elements link the transmission of the complex over time and space. However, Loeb [151] goes further and eventually links the Kuksu cult to many distributed over the Americas in agreement with a proposal by Father Schmidt [152]. He postulated, in hyperdiffustionist fashion, an ancient cult brought to the Americas by the first arrivals, the survivals of which could be seen spread over the two continents. This seems unlikely and the evidence appears to support the idea of a spread of the cult from the Southwest.

The Sanusi and The Secular and Religious Foundations of Government

Evans-Pritchard [81] describes the establishment of the Sanusi organization as the original work of one man, a scholar and missionary of Islam. Study into the history of the Sanusi has been complex, as has their description and has changed depending on the nature of the colonial enterprise and particular view of the relation between the Sanusi and Ottomans as well as other sects of Islam in the Middle East [153]. The particular dogma of the Sanusi was based on a tradition of saints in Islam as guides and judges, guides in the teaching of the practice of Islam to the common people, especially the Bedouins and judges in the resolution of conflicts. The spread of the Sanusi after its foundation was remarkable and comprehensive. The construction of rest houses and centers of teachingwere established over much of North Africa, along the coast and into the Sahara, from Senegal to Darfur and Chad.

One idea is that it was established de novo by Sayyid Muhammad ibn Ali as-Sanussi (1787 to 1859, known also as the Grand Sanusi), who was early influenced by Sufi thought. He studied first in Fez and then preached in the Fezzan (and southern Algeria as well as northern cities of today's Libya) and then went to study in Cairo at the Al-Azhar University. There he came into conflict with local Muslim thought he believed had adapted to Ottoman rule. He left to Mecca where he came into contact with Ahmad ibn Idris al-Fasi, head of Khadirites (or Khidriya Darwishes). Conflict over doctrine with the conservative Meccan establishment, especially the Wahhabis led to exile and eventual return to North Africa where he began his task of creating an indigenous organization separate from the Ottoman rulers and tribal structure [154].

A comprehensive organization that provided production, taxation, education and judicial remedy was integrated within a religious structure. Infact, Ahmida [155] centers our attention on the idea of the creation of an economic and political entity. Triaud [156] provides a unique picture of the Sanusi from diaries of leaders and a background of their interaction with various ethnic groups like the Tuareg.

The tribal situation before the construction of the Sanusi organization is described as a tribal confederation. After the official conquest of the coast line by the Ottomans no real interference in the affairs of the tribes was attempted. This allowed tribal politics to continue as it had for centuries, but was characterized by intermittent warfare. The Sanusi built up in the void a structure within the tribal confederacy in which the religious status of the order functioned as a buffer to conflict and a center of trade and taxation to support services beneficial to tribal members.

Like the Kuksu religion it spread without force to transform the political and economic infrastructure of the tribal organization. Evans-Pritchard [81] argues that the Senusi created a parallel state to the Ottomans on the coast, and likens it to the state created in Saudi Arabia, but this is difficult to defend as the relationship between the Saudis and the Wahhabis led to the successful Saudi state largely by the efforts of the British colonists to dislodge the Ottomans. We must keep in mind that the Ottomans had repressed the rebellion led by Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab under the command of Pasha Ali's sons between 1801 and 1818 when Wahhab was captured, taken to Istanbul and executed. Compared to this the Grand Sanusi did accomplish the creation of an indigenous state [157,158]. Other views emphasize the interest in the revival of the concept of a united Umma in Islam as the main drive [154,156].

The Tiahuanaco Cult as a Religious and Peaceful Transformation

From these two examples, we can see that changes in material culture and symbolism as well as economic and political organization can change without military force. Tiahuanaco, as a site considered to be a locality of Native American civilization, has gone from being considered "a vacant ceremonial or pilgrimage centre" after its examination by Squire in the Nineteenth century [3] to being the capital of a military expansionist and colonizing state following the work of Ponce [159], to recent arguments of the spread of a ceremonial cult [3]. One wonders how there could there be such a divergent view of the site and what changed in the evidence to promote it? Recent interpretation of the Tiahuanaco religion has been based on the natural setting and ethnographic analogy with the existing Aymara communities [160].

Certainly the "weeping god" figures, the men wearing puma or condor masks with flowing capes as if running can be considered spiritual, or theatrical or perhaps part of a game of sorts. Is it necessary to associate them with a religion? The mascots of an American or British football team could play this part. In fact, without written documents much has been inferred from the spread of cultural traits, including architecture. It is argued that Tiahuanaco arose from a "community-focused cult" to a pan-regional theocratic state. This is believed to have been held together by recurring bout of ritual drink memorialized in ceramic iconography. While the evidence is obscure at best, it might be imagined to function perhaps in ways similar to that described by Mauss [161] for linking lineages and power. This idea was suggested by Adams [71] to apply to Mesoamerica from the work of Diakonoff [162] on Sumerian documents. However, in his model a theistic control passed to a military clan system.

There is certainly no question that some social force originated at Tiahuanaco and spread across many pre-existing political and cultural entities. The only question is how this took place. Burials from Tiahuanaco provide little information on the nature of society. These are divided into three groups by some researchers [163], a chiefly elite, a warrior caste and a class of commoners. Interpretations of social institutions from burials are a notoriously subjective enterprise as Binford [164] has shown. Terms are often used with reference to Tiahuanaco, like "sudden termination," or "decadence of" [165]. Without reference to historical records we are adrift in suppositions. Christianity and Buddhism both spread with military support as did Islam [13,74]. How does one discern the difference? A final alternative would be a reinterpretation of an existing religious structure, as in the Ghost Dance, but later given militaristic ends as it became entrenched. Though this failed with regard to the Ghost Dance, elements that have survived into the historical period, like the oracles, emphasize a popular religion [7]. Though this last reference is to Huari and the idea that there is a direct relationship between the Tiahuanco cult and that in Huari.

Nevertheless, Janusek [3] gives a reasoned explanation of the ritual origins of Tiahuanaco, drawn from the natural orientation of the landscape marked by mountains and local aquifers. Much has been made in the literature of "ceremonial" structures and imputed to ball courts as places of religious and political ideology and human sacrifice. This has often been broached in appropriate scholarly hesitation as most of the source material is derived from the Spanish conquerors whose own home countries at the time blazed with the fires of human sacrifice in the form of real and imagined heretics [166,167].

In many of the references concerning Tiahuanaco there appears the idea of pilgrims and religious shrines and complexes (e.g., Vranich [168]). It invokes comparisons with the development of Buddhism in Tibet from the Bon-po animistic foundation, especially the concept of nature as the central reference point [42] though Buddhism triumphed by the military intervention of Mongol armies [169].

If we can confidently interpret the evidence in a way that acknowledges the facilitation of landscapes for meditation of cycles and natural scenes as well as to accommodate pilgrims in their movement across a vast region in Tiahuanaco, we can see parallels with the development of the Sanusi and the Kuksu movements. If we combine these elements with the relative speed in which these three phenomena spread affecting architecture and other cultural traits we might see them as close enough in form to identify Tiahuanaco as primarily a spiritual social movement and not a military and colonial one.

Conclusions and a Framework for a Context of Current Conditions

The problem of how to determine from the archaeological record changes that might be evidence of war or of religious cause is difficult to approach. That is not to say that "violence" cannot be acted out as religious rite, as in the Dionysus cults of ancient Greece or certain shamanic practices [40,170] but there should, in a warfare context, if we can make uniformities across cultures for war (which is perhaps a stretch), be systematic evidence which is also lacking. Arkush [171] uses this to escape the logic of the lack of this evidence by saying, "As this review illustrates, warfare in the Andean highlands varied in intensity and scale over time". What is seen is a few clusters of "trophy heads" which in other contexts can be interpreted in a wide variety of uses from ancestor worship to ritual consumption which are poorly described, and injuries to crania.

Removal of heads of serious criminals and their sequester in sealed pots was done in Tibet in the belief to prevent future problems with the individuals [41]. Also, Fortune [172] reports that ancesters' crania were routinely carefully preserved in Manus religion, to elicit their aid to the living, only to be discarded if they failed to protect. While Lawrence Angel pioneered the study of prehistoric activity patterns, Bridges [173] notes the frustration in failing to find a correlation between weapon use and osteological features. Rose [174] summarizes the conditions in the archaeological record for the supposed site of Troy, indicating that walls had been repaired at different times, though evidence of earthquakes may also be a factor, while charred timbers and parts of human skeletons are also used to prove warfare, and new types of pottery to show replacement of one people by another, though diffusion could also be an explanation.

Caldararo [5] used the comprehensive survey of the archaeological literature by Willey and Sabloff in 1974 as a source to study the structure of the archaeological report [5,175]. This study demonstrated significant changes in reporting and the means of identifying and quantifying features in sites and correlating these with other sites in regions. But this appeared without general agreement in terminology or methodology by practitioners until the years just prior to Caldararo's study [5]. A similar dilemma faced the investigations of Ammerman and Cavalli-sforza [176] in trying to determine if agriculture and food production had spread into Europe by migration of peoples or by diffusion of knowledge. They rely eventually on a mathematical model and theories of demic expansion based partly on certain HLA genes. But there are significant problems concerning such models [177]. The expansion of Bantu-speaking farmers also addressed a similar problem in archaeology [178] with the additional complication that many of the pre-existing peoples (hunter and gatherers) were bound up in the wave of expansion in mutualistic relationships that, in some cases, still exist today. In tracing changes found in the archaeological record Piggott [179] concludes that observed changes in house types, burials, pottery and weapons after 3,000 B.C.E. seem to represent the invasion or migration of peoples into Europe, a scenario paralleled by James [180] who concentrated mainly on burial evidence, though Binford [164] was unconvinced.

How to discern evidence of this meeting of peoples, peaceful, conquest, conversion or extermination is unclear. Evidence of fire, ash for example, has been noted, but does this indicate that during conquest the victors always set fire to the spoils of their triumph, certainly a rather poorly thought out economic practice. Though as Vandkilde [4] notes we should not assign rationality to actors in the past; we do know that in the Spice Wars the European powers often fired the spice groves to produce temporary profits in high prices, but the long term consequences were lost to them [181].

Also ash could also be associated with the burning of homesteads when they are abandoned by their owners due to death, disease or failure of crops, etc. The character of abandonment of sites without violence is a subject of some value, and it is rare that an excavator speculates on abandonment in detail, as at Mawgan Porth [182]. The same question arises with regard to unburied dead or sudden changes where burial practices indicate hurried burial in mass graves that could be the result of epidemics, as is known from historical accounts of the European Black Plague [183].

In proposing the association of large scale cultural change to religious conversion rather than conquest, I acknowledge that the two are often related in history. For example, the Mongol conquest of Tibet established Buddhism at the expense of the indigenous Bon-po religion (Hoffman, 1961), the spread of Islam and the Christian Crusades and colonial conquest of the Americas are other examples. Often this is part of a pattern of systematic violence as in the case of the spread of Islam and Christianity. Once Christian states had achieved what Toynbee [184] called the "tyranny of Christianity" its extermination of competing beliefs spread across the globe. As Caldararo notes concerning Japan and Christianity [185], the Japanese saw the arrival of the west as a confrontation of three separate elements of attack, trade - which introduced novel items and disrupted local products and lifestyles, religion - that caused a plurality of belief and produced violence that undermined the solidarity of the Japanese resistance, and military warfare.

Systematic injuries are associated with some cultural acts of criminal justice, like crucifixion, and are seldom found to appear in large numbers except when widespread social unrest occurs as in the Spartacus rebellion. Though certain forms of mutilation, like decapitation, which occurred with the removal of hands (as in the case of Cicero), were the result of civil unrest and not invasion in Roman society (Cicero, 66-7 BCE; Josephus, 75 CE; [186]).

Vencl [187] argues that the absence of warfare studies in prehistoric archaeology reflects the inadequacy of archaeological sources. I would disagree. In Caldararo's study of the archaeological report [5] it was clear that the theme of war was prevalent in reports made prior to about 1840, using Willey and Sabloff [175] as a guide. This is their "Speculative Period". Much of the discussion derived from this theme was based on speculation and contemporary ideas of human society, one seen in the context of the Napoleonic Wars and the constant conflict between European powers up to that time, European mythology and Classical history, especially that of the Greeks. The period following this to 1914 is termed the "Classificatory-Descriptive Period" and is focused on site description, association of sites with historical periods but with a de-emphasis on speculation. Their third period is the "Classificatory-Historical" characterized by a different theme that of repudiation of speculation without considerable evidence and typified by scientific methods in analysis, measurement and recording. This period closes in 1960 and there begins the final period, the "Explanatory Period" where growing criticisms of earlier certainties in history (and interpretation, note that of Walter Taylor [188] especially) began to congeal around attempts to understand culture and human behavior in the past. This brings us to Postprocessual archaeology in the United States and the response of many Europeans to it (e.g., Daniel [189]).

It seems from this brief survey, though based on extensive earlier ones, that Vencl [187] is mistaken, as is the assertions of Vandkilde [4] who proposes that archaeological interpretation has reflected one of two "stereotypic tales" about human nature. Rather than his argument that report contents and focus are the result of attempts to rationalize war in the past, it seems we are on firmer ground in noting the reflective context of archaeological dialogue and debate over the past 200 years. It does appear a bit contradictory to assume, as Vandekilde [4] does, that the men writing archaeological reports who were experiencing the most violent and destructive wars of the past 2000 years, would neglect evidence of war in the archaeological record as they found it. Unless we assume a general psychological syndrome to explain this neglect, I think it is best to hold to the ideological changes in the nature of the archaeological report as a more reasonable explanation.

It is no mystery why there is such concern over the situation in much of the world today made unstable by populism and religion. From the United Kingdom to China nations are beset by division and strife. In the area of Africa which has been our focus we see conflict and crisis. Articles in the media range from predicting continued civil war to years of legal conflict over a separation of assets and people. Most Western news desks acknowledge a systematic support by the governments and local populations immersed in development opposition and religious conflict. In the north there has been an "Arab Spring" which has left a number of states in crisis. In Sudan a division of north and south resulted from mass terror driven partly by religion as in the massacres of the Jagawineed/Janjawild [190] and the mounting suffering of the displaced refugees. But civil war blazes from Mali to Ethiopia and south to the Congo. International arms merchants and development agencies spark many of these conflicts as does the potential to exploit resources. These are the sources of arms used to kill and drive people from their homes. Often there is a narrative of colonial history that created the conditions of conflict, for example, that the Jagawineed originated in the defeat in Chad of militias created or supplied by Libya under Gaddafi in the 1970s who fled into Darfur [191]. There are a number of other explanations, as in the colonial division of the Sudan. Increasingly since then, a variety of actors from the USA to the Sudan government began to arm and support local tribes like the Dinka and Nuer.

Usually the developed north is compared with an underdeveloped south with little explanation for the situation. There is an implied understanding that this is how things have always been. But when one looks at the history of the Sudan, and the adjacent areas of Libya, Fezzan and Tibesti, etc. and of the background of current events, the situation is less clear. For several thousand years the Egyptian Empire and various Sudanese peoples and kingdoms fought for domination and self-determination in the Western Sahara and Sudan. From a variety of states that existed in the Kanem-Bornu and Kano areas in the 7th century B.C.E. or the kingdoms of Wadai and Darfur in the 18th and early 19th centuries we can trace a long history of established functioning organizations.

This was continued with the rise of Islam and the failure of its armies to conquer the Sudan. The history of the Sudan is linked to that of the Horn of Africa as well as the Arabian Peninsula, especially that of Yemen, though some African scholars dispute the significance of these contacts (see Cheikh Anta Diop [192,193]). Islam permeated the Sahara, but largely by missionaries. In 1820 Muhammed Ali Pasha, an Ottoman official ruling Egypt, accomplished this task and set his son on the throne. However while the colonial powers focused attention on the political entities, they ignored a more substantial trans-Saharan, trans-national organization that grew up around the Sanusi movement.

The Grand Sanusi attempted to stay independent of both the Ottomans to the east and the colonial powers, France to the south and the Italians and British to the north. Nevertheless, colonial aggression advanced, especially the French who invaded across the Sahel and from the west, destroying indigenous kingdoms as they came. The Grand Sanusi refused to join the rebellion of the Mahdi, hoping to keep his organization from being embroiled in war. This failed and eventually the defeats of the native resistance and the massacres that followed left no alternative but war. By 1911 when the Italians invaded Libya, colonial powers had destroyed the Sanusi organization, and in almost all the oases, the Sanusiya lodges.

From 1879 on European powers intervened across North Africa and in 1882 British ended independent rule in Sudan. After the Mahdist revolt was suppressed they consolidated their hold on the country. To a large extent the crises in Libya, Sudan, Mali and instability in Tunisia and Egypt can be traced to the failed Colonial Wars, institutions and disorganization of the native social structures including the Sanusi.

Two of the most significant works on the peoples of the Sudan were written by S.F. Nadel [194-196], an anthropologist who argued that anthropology had to be active and that a "value-free anthropology is an illusion" [197]. It is incontestable that the Sudan as a modern state is the product of British colonialism. In the basic infrastructure of roads, bridges, city design and management, bureaucratic organization, educational patterns of employment as well as economic history of investment and banking, all hark to British influence. As mentioned above, pre-existing systems were crushed. The British colonial authorities had a long history in the Sudan by the time Nadel arrived in 1938 after having proved his abilities at research in Nigeria under the International African Institute. His tenure after the Nuba research in 1941 included assignment with the British Military Administration. Allied interests in the military assets of the Anglo-Sudan were substantial to counter German designs on Egypt.

As in other parts of the British Empire, conflicts with tribal peoples had proven to be uneconomical at best, and in the context of growing threats of war in Europe a more cooperative arrangement was sought. Integrating the Nuba and other peoples in the Sudan into a supportive unit for Allied purposes was needed and it could be seen that pagan tribes like the Nuba could be used in the future as buffers to militant Islam from the North. Containing Islam and Arab influence was an important colonial goal. Government policy attempted to halt this influence by preventing development and population movements from the North and led to a poorer economic base in the south of Sudan than the Islamic north. Nadel, unlike his colonial administrators, looked upon the Christian missionaries with the same distaste as Arab infiltrators. In both cases they were elements that would cause the Nuba both discomfort and displacement.

The British banned movement of people from north and south, thereby insuring a division that was basically oriented around the Islamic North and animistic South with some Christianized peoples. Independence led to war between these two parts and different religions in 1955 ending in 1972. The more modernized and developed north had the advantage. The war ended with the Addis Ababa Agreement which guaranteed a semi-independent South. This ended in a new civil war when the central government decided on a federalized state and no international pressure was brought to bear to save the Agreement. War in the Sudan has generally been acted as proxy wars of surrounding nations with Ethiopia playing a central role, but Egypt and Libya involved as well. The real prize in the post World War II period was the mineral and oil resources in the south. With no central organization, the south was victim to the intrigues of foreigners and transnational corporations and their clients. Instability will provide access to tremendous profits so it is unlikely that any peaceful transition to nationhood could be achieved unless the unreal possibility that all outside interests could be kept out and some southern regional solution be fashioned internally.

Of our three examples, only that of Africa sees fragments of that past spread of religion and the framework for communication and community at these provided their areas. In the Americas these are only a footnote to contemporary political and religious conditions, but in Africa, and especially North Africa, the collapse of indigenous systems due to colonialism has reeked havoc across the continent. While the Sanusi phenomenon was peaceful it has been replaced by more aggressive forms as in al-Queda and ISIS.

References

- Braudel F (1969) Memory and the mediterranean. Vintage Books, New York, USA.

- Blackman HJ (1961) Political discipline in a free society. George Allen & Unwin, London.

- Janusek JW (2006) The changing 'nature' of Tiwanaku religion and the rise of an Andean state. World Archaeology 38: 469-492.

- Vandkilde H (2003) Commemorative tales: Archaeological responses to modern myth, politics and war. World Archaeology 35: 126-144.

- Caldararo NL (1984) A note on the archaeological report. North American Archaeologist 6: 63-80.

- Redfield R (1957) The primitive world and its transformations. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

- Bruhns KO (1994) Ancient South America. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Steward JH, Faron LC (1959) Native Peoples of South America. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Clark AH (1918) The unstalked crinoids of the siboga expedition. Biodiversity Heritage Library 1-300.

- Radin P (1920) The sources and authenticity of the history of the ancient Mexicans. University of California Press (University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 17/1), Berkeley.

- Goldstein P (2005) Andean Diaspora: The tiwanaku colonies and the origins of south american empire, Gainsville, University Press of Florida.

- Caldararo N, Kahle TB (1989) An analysis of the present status of research into the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin. Restauro 95: 297-305.

- Caldararo Niccolo (1994) Lost libraries of the Americas. Library History 10: 9-18.

- Caldararo Niccolo (2004) War, Mead and the nature of criticism in Anthropology. Anthropological Quarterly 77: 311-322.

- Caldararo Niccolo (2004) Sustainability, Human Ecology and the Collapse of Complex Societies. Lewiston Edwin Mellen Press.

- Binford Louis R (1986) The hunting hypothesis, archaeological methods, and the past. American association of physical anthropologists annual luncheon address, April. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 30: 1-10.

- Caldararo,Niccolo (2016) Human sacrifice, capital punishment, prisons & Justice: The function and failure of punishment and search for alternatives. SSOAR 41: 322-346.

- Vaillant GC (1944) Aztecs of Mexico. Pelican Books, New York.

- Boone Elisabeth H (1984) Ritual human sacrifice in Mesoamerica. A Conference at Dumbarton Oaks, Oct. 13th and 14th, 1979, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

- Goeffery Brereton (1373) Chronicles. (1977 edn), Penguin Books, New York.

- Tringham Ruth (1974) The concept of 'civilization' in European archaeology', in the rise and fall of civilizations. In: Lamberg-Karlovsky CC, Jeremy A Sabloff, Menlo Park, Cummings Publishing Co, 469-485.

- Ferguson Brian R (1992) Tribal warfare. Scientific American 108-113.

- Caldararo Niccolo (2015) Local resistance in the era of capitalist globalization: Clash of cultures in the 21st century. The IUP Journal of International Relations 9: 7-22.

- Curry Andrew (2016) Slaughter at the bridge: Uncovering a colossal Bronze Age battle. Science 351: 1384-1389.

- Ubelaker Douglas H (1974) Reconstruction of demographic profiles from ossuary skeletal samples. A Case Study from the Tidewater Potomac, City of Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Oldenbourg Zoe (1961) Massacre at montsegur, A history of the albigensian crusade, London, Widenfield and Nicolson.

- Ramet, Sabrina P (2002) Balkan Babel, Cambridge, Westview Press.

- Wilkerson Jeffrey K (1984) In search of the Mountain of Foam: Human sacrifice in Eastern Mesoameria, in Ritual Human Sacrifice in Mesoamerica: A Conference at Dumbarton Oaks. In: Elizabeth P Benson, Elizabeth H Boone, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, 101-133.

- Bonner Michelle D (2005) Defining rights in democratization: The argentine government and human rights organizations, 1983-2003. Latin American Politics and Society 47: 55-76.

- Falconer Bruce (2008) The Torture Colony: In a remote part of Chile, an evil German evangelist built a utopia whose members helped the Pinochet regime perform its foulest deeds. The American Scholar 77: 33-53.

- Levak Brain P (2006) The witch-hunt in early modern europe. Pearson Education.

- Keitt Andrew (2005) The miraculous body of evidence: visionary experience, medical discourse and the Inquisition in Seventeenth century Spain. The Sixteenth Century Journal 36: 77-96.

- Piggott Stuart (1954) The druids and stonehenge. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 9: 138-140.

- Brisby Claire (2009) Druids at drayton: Dipping into antiquarianism before the society of antiquaries (1717). The British Art Journal 10: 2-8.

- Owen James (2009) Druids committed human sacrifice, cannibalism? National Geographic.

- Pijoan, Carmen Ma, Lory Josefina Mansilla (1997) Evidence for human sacrifice, bone modification and cannibalism in ancient Mexico. In: Debra L Martin, David W Frayer, Troubled Times: Violence and Warfare in the Past. Gordon and Breach, OPA Amsterdam, 217-240.

- Villa Paola, Bouville Claude, Courtin Jean, et al. (1986) Cannibalism in the Neolithic. Science 233: 431-437.

- White Tim D (1992) Prehistoric Cannibalism at Mancos 5MTUMR-2346. Princeton U Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

- Villa Paola, Cannibalism in the Stone Age. Anthroquest, Leakey Foundation, Summer, 9-12.

- Eliade Mircea (1964) Shamanism. Princeton U Press, Princeton.

- Kawaguchi Ekai (1909) Three years in Tibet, with the original Japanese illustrations. Adyar, Madras, Theosophist office, Theosophical publishing society, Benares and London.

- David Snellgrove, Richardson (1995) A culture history of Tibet. Shambahala, Press, Boston.

- Robert Henry Codrington (1891) The Melanesians: Studies in their anthropology and folk-lore. Oxford, University Press.

- Richard Sugg (2011) A history of cannibalism. The Guardian.

- C Richard King (2000) The (Mis) uses of cannibalism in contemporary cultural critique. Diacritics Spring 30: 106-123.

- David Webster (1997) Studying Maya burials. In: Stephen L Whittington, David M Reed, Bones of the Maya: Studies of ancient skeletons. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC.

- Ubelaker, Douglas H (1981) The Ayalan cemetery: A late integration period burial site on the South Coast of Ecuador, Smithsonian Institution Press, City of Washington.

- Schele Linda, Freidel David (1990) A forest of kings: The untold story of the ancient Maya, William Morrow, New York.

- Dennis Tedlock (1985) Popol Vuh. Simon and Schuster, New York.

- William Gates Friar Diego de Landa (1978) Yucatan before and after the conquest. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, USA.

- Finkelstein JJ (1963) Mesopotamian historiography. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 107: 461-472.

- Joan Goodnick Westenholz (1984) Book review: The Sargon legend: A study of the Akkadian text and the tale of the Hero who was Exposed. J Near Eastern Studies 43: 73-79.

- Mary Beard (2015) SPQR: A history of ancient Rome. Liverright Publishing, London.

- Niccolo Caldararo (1995) Storage conditions and physical treatments relating to the dating of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Radiocarbon 37: 21-32.