Reconstructing the Social Sciences and Humanities: Antenor Firmin, Western Intellectual Tradition, and Black Atlantic Thought and Culture

Abstract

In 1885, the nineteenth-century Haitian lawyer, statesman, anthropologist, and Egyptologist, Joseph Antenor Firmin (1850-1911), published his work, De l'egalite des races humanines (The Equality of the Human Races) as a rebuttal to Arthur de Gobineau's, "Essai sur l' inegalite des races (An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races). In this article I argue that Firmin's critique of western anthropology is not a vindication for afrocentrism as expressed in the works of afrocentric scholars like Molefi Kete Asante and others. Instead, it is a call to highlight the contributions of African people to intellectual thought and development as it has come to be embodied in the universal ontology and epistemology of science. Be that as it may, in this work I want to continue Firmin's position by demonstrating the African contribution to social and scientific theories by highlighting the scientism of the African people of Haiti as revealed by the religion of Vodou, its epistemology (Haitian/Vilokan Idealism), and its form of system and social integration, the Vodou Ethic and the spirit of communism. Essentially, like Firmin, I assume, against the noiriste and Afrocentric positions, science as a human universal, which began in Africa, and has now reached maturity in Western society. This work seeks to highlight the African/Haitian contribution to the scientific process as encapsulated and revealed in Paul C Mocombe's [1] social theory and method of "phenomenological structuralism" thereby reconstructing the social sciences and humanities to account for the contribution of black Atlantic thought and culture.

Keywords

Post-colonial theory, Vodou ethic and the Spirit of communism, Religiosity, Black diaspora, Dialectical, Anti-dialectical, Phenomenological structuralism

Introduction

Joseph Anténor Firmin (1850-1911) was born in Le Cap, Haiti in 1850. Schooled in Haiti and Paris, in 1885, the nineteenth-century Haitian lawyer, statesman, anti-racist intellectual, anthropologist, and Egyptologist published his magisterial text, De l'égalité des races humanines (Anthropologie positive) (The Equality of the Human Races) in Paris in the form of an impassioned "scientific rebuttal" to Arthur de Gobineau's scientific racism and, particularly, against his central thesis of the ontological superiority of the Aryan-White race and the ontological inferiority of the Black race. Gobineau articulated his ideas on the subject of racial hierarchy and racial essentialism of the human races, and correspondingly the history and achievement of the white race in modernity in his controversial and unfortunate text, Essai sur l'inégalité des races (An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races) (1853-1855). For Gobineau, the history of the world in the strictest sense of the term is a racial accomplishment, the accomplishment of whiteness. On the contrary, Firmin argued that the Aryan race does not name the conclusion of human history and the history of an achievement, which the French anthropologist and other proponents of white ideology and white supremacy celebrated. The Haitian intellectual also challenged Western racist attitudes towards Blacks and the logic of nineteenth century's scientific racism for ranking the Black race discriminately and deliberately in the lowest racial ladder of the racial hierarchy of the human races and in the metanarratives of human history.

Although Firmin challenged Western nineteenth century racist attitudes towards Blacks by pointing to the African contribution to Egyptian and Western civilizations, he was not an Afrocentric in the sense of the ethnological, négritude, noiriste, and contemporary Afrocentric movements of the twentieth century, which viewed African culture and civilizations as different and unique from European ones based on race and culture. The latter theorists asserted and assert "that members of the black race shared a common psychology (acquired or innate), that their social mores were different from those of whites, that they should therefore cease to accept European standards and should develop a specifically African way of living" [2]. Firmin, conversely, posited that the various human races were equal and differed in no important respect, and that the backwardness of the African race vis-à-vis whites was due to slavery and colonialism. He, therefore, wished to demonstrate, in his works and politics, the capacity of members of the black race to achieve progress and to build a civilized community according to European standards, which he accepted as being of universal application [2-4].

The purpose of this present work is twofold: first, I want to suggest, building on the works of David Nicholls [2] and Laurent Du Bois [4], that in his anthropological work Firmin is a universalist. He was not proposing that people of African descent are different from whites or view the world differently from them, a la the Afrocentric's and noirisite's positions. On the contrary, his highlight of African contributions to civilization was to demonstrate their abilities, which are similar to whites who would build on, and continue, the universalist project of Egyptian/Ethiopian civilizations via the universality of the Enlightenment project. Second, I want to continue Firmin's position by demonstrating the African contribution to social and scientific theories by highlighting the scientism of the African people of Haiti as revealed by the religion of Vodou, Haitian epistemology (Haitian/Vilokan idealism), and their form of system and social integration, lakouism and the Vodou Ethic and the spirit of communism, respectively [5]. Essentially, like Firmin, I assume, against the noiriste and Afrocentric positions, science as a human universal, which began in Africa, and has now reached maturity in Western society. In this work, I seek to highlight the African/Haitian contribution to the scientific process as encapsulated and revealed in Paul C. Mocombe's [1] social theory and method of "phenomenological structuralism," thereby reconstructing the universality of the social sciences and humanities to account for the contribution of black (Haitian) Atlantic thought and culture, without any references to racial essentialism, which for me was the intent behind Firmin's [3] work, or reactionary logics of oppression as embodied in constructs such as "double consciousness," Afrocentrism, noirisme, black modernity, etc.

Background of the Problem

In his anthropological work, The Equality of the Human Races, Antenor Firmin sought to refute the support for the principle of racial inequality buttressed by prominent scholars from Immanuel Kant to Ernst Renan by highlighting the brilliance of African people and their contribution to civilizations [3]. According to Firmin, there was only one human race, "endowed with the same qualities and defects, without distinctions based on color or anatomical shape. The races are equal" [3]. The notion of the inequality of the human races, Firmin would go on to argue, was rooted in the history of slavery and colonialism as opposed to scientific fact [4]. As such, to demonstrate the equality of the black race to whites, Firmin would go on to insist that, "Egyptian civilisation is the fountainhead from which sprang the Greek and Latin cultures, and that the development of the arts and sciences among white people of the West rested upon an African foundation. Caucasian presumption, he observed, could not abide the idea that the whole development of human civilization originated with a race which they considered to be radically inferior to themselves" [2]. Firmin, like his European counterparts, would go on to use personal accounts to further make his point [4]. Nonetheless, in spite of the less than scientific approach to the latter part of his work, Firmin would give rise to the negritude, Afrocentric, and American anthropological traditions of Franz Boaz which sought to demonstrate the Africanisms found among African people in the diaspora and their contribution to the development of Western science [2,4]. For Firmin, like many Haitian writers of the nineteenth century, civilization (arts, culture, and science) had originated in Africa; however, slavery and colonialism had retarded African people and their progress, which gave rise to European civilizations. So in essence Firmin does not question the universality of the scientific progress that European culture has made in the arts and sciences since at their base is African culture [2]. He only questions its omission of the African contribution to that universal process, and debasement of its people [3].

I do not fundamentally disagree with Firmin's thesis. I only reject the trajectory that the thesis has taken in the constitution of Afrocentric and noiriste theories emanating out of the adaptive-vitality and pathological-pathogenic debates in the American and French anthropological traditions. That is to say, I accept the Firminian understanding that at the base of European civilization, culture, and progress is African (Egyptian/Ethiopian) civilization, and ultimately the European manifestation is at a level superior to anything found in Africa or Haiti, contemporarily, as a result of slavery and colonialism. However, I reject the racial essentialist viewpoint of many Afrocentrics and noiristes that the African mind, as a result of race, produced something other than the universalism purported by Western science. Like Firmin, I am an universalist and reject the correlation between race and scientific progress, all persons are "endowed with the same qualities and the same faults, without distinction of colour or anatomic form. The races are equal; they are all capable of achieving the noblest intellectual development, as they are of falling into the most complete degradation". Hence, for me, in keeping with the universalist and human essentialist logic of Firmin, the key is highlighting the contribution of African people to the universal project of Enlightenment scientific thought and progress as opposed to concocting and reifying a new racialist discourse guised in the pseudoscience of noirisme and Afrocentrism, which attempts to substantiate the position that members of the black race shared a common psychology (acquired or innate) that gave rise to a distinct-particular-African worldview and science other than the scientism and civilization of the West. The latter position is retrograde. In my view, like Firmin, African people produced an original universal science that was interrupted by slavery and colonialism. The Greeks and Latins would build on its principles, which became the driving forces of the Enlightenment project of the West. Hence, in reconstructing the sciences and humanities to account for the African contribution, the aim is to highlight the parallels between the universal elements highlighted by African science and their further development in the West as opposed to reverting back to a retrograde position of reconstructing and reifying the particularism of the African worldview and interpellating and subjectifying black people to that particularism under the pseudo-science of noirisme and Afrocentrism or reactionary theories of oppression highlighted by constructs such as double consciousness. The aim ought to be on reconstructing and reifying the universalism of the African worldview in order to further the scope of the scientific process as encapsulated in the principles reified in the West. Paul C. Mocombe's phenomenological structuralism in the attempt to resolve the structure/agency problematic of the social sciences by reverting back to Haitian epistemology, for me, captures that Firminian initiative more so than noirisme and Afrocentrism, which wants to reify and hold on to the particularism of the original African universalist project that contributed to and continues via the Enlightenment project of the Europeans.

Theory and Methods

According to Paul C. Mocombe [1,6-9] his theory of phenomenological structuralism is a product of Haitian epistemological Idealism, Haitian/Vilokan idealism, which is a product of the demystification, demythologization, and rationalization of Vodou metaphysics and physics as revealed in the evidence and logic of contemporary physics and social theory, i.e., quantum mechanics, phenomenology, structurationism, materialism, and structural Marxism. Vodou is the religion and science of the African people of Haiti; the basis around which they organize their ethical worldviews, medicine, aesthetics, and form of system and social integration. It is out of the epistemological logic, a form of Haitian transcendental idealism and realism, of Vodou, as it relates to contemporary quantum and social theory that Mocombe would construct his phenomenological structural theory and methodology in order to resolve the structure/agency problematic of the social sciences. Mocombe extrapolates what is universal from the African/Haitian scientific position, Vodou, and ties it to the universalism of the scientific project of the West in order to account for the African contribution to social theory and the sciences as opposed to relying on any references to racial essentialism (innate black psychology) as found in noirisme and Afrocentrism.

According to Mocombe, for the Africans, Vodou is a monotheistic (scientific) religion in which the one God, Bon-dye, or Gran-Mét, the primeval pan-psychic field, is an energy force that gave rise to a sacred, cosmic, and geometrical world out of itself. Everything that is the world, universe, galaxies, animate and inanimate objects, etc. are a manifestation of Bon-dye, and are sacred. Thus, unlike the jealous and barbaric God of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, which stands outside of spacetime and makes human beings, the fallen, the superior creation of its design, i.e., the earth, which is to be exploited and dominated for human happiness and wealth. The God of Vodou has no such place for the human being. Bon-dye is space time, and the human being is no different from any other creation that is a part of this being. The aim of the human individual is to maintain balance, harmony, and perfection between nature/God, the geometric laws of creation, the cosmic forces (which aided Bon-dye in creating the multiverse), the community, and the individual.

Out of Bon-dye, the geometric laws of creation and the cosmic forces (lwa Legba, Gede, Zaka, Damballah, and Ezili) were created to assist Bon-dye in creating the multiverse and habitable worlds (See Table 1). According to Vodou mythology, one of Bondye's first creations when he fashioned the world was the sun (identified with the lwa, i.e., concept, Legba in Haitian Vodou metaphysics). Without its existence, lwa yo (concepts, ideas, and ideals by which humanity ought to recursively organize and reproduce their being-in-the-world), human beings, and all the multiplicity of things could not exist. All derive from this primordial light. In Vodou, the sun with which Legba is identified is a regenerative life-force whose rays cause the vegetation to grow and ensure the maturation and sustenance of human life. Legba is the patron of the universe, the link between the Godhead and the universe, the umbilical cord that connects the universe to its origin. Bondye fashioned the universe; Legba has nurtured it, has fostered its growth, and has sustained it. Legba is also said to be androgynous; hence, his vévé (artistic symbol) contains the symbol of his sexual completeness, and he is invoked in matters related to sex. He is the cosmic phallus. Both as phallus and as umbilical cord, Legba is the guarantor of the continuity of human generations. Just as Legba initiates time, so Gede ends time, for he is the master of Ginen who rules over death. In a sense, Gede is Legba's opponent, for whereas Legba as the sun is omnipresent during the day, Gede is lord of the night and is symbolized by the moon. Whatever, Legba conceives, Gede aborts; and whatever Legba sustains Gede destroys, for he is the lord of death, the master of destruction of things. Although these two divine forces appear to have opposite functions, and indeed are inversions of each other, they nevertheless are similar in many ways, for both participate in the creative forces at opposite ends of the spectrum of life. Damballah, the gentle snake of the primal seas is identified with eternal motion in the universe. This motion is characterized by the passage of all physical phenomena from birth to decay, and produces the physical displacement of objects in space and in time, manifests itself in the incessant motion of the waves of the ocean, the waters of springs and rivers, ensures the alternation of day and night, and impels the cyclical motion of the astral bodies. In short, Damballah is a living quality expressed in all dynamic motion in the cosmos, in all things that are flexible, sinuous, and moist, in all things that fold, and unfold, coil and recoil. In humans, this energy-force is the giver of children. It is identified not only with the eternal motion of human bodies but also with motion as seen in the cycle of life and death and in the passing of human generations. If motion is ensured by Damballah, and if, as generating principle, the phallus is symbolized by Legba and Gede, Ezili represents the cosmic womb in which divinity and humanity are conceived. She is the symbol of fecundity, the mother of the world who participates with the masculine forces in the creation and maintenance of the universe. As mother, Ezili cooperates with the sun lwa Legba, who ensures the florescence and nurture of all living things. When she cooperates with Gede, she symbolizes Ginen's cosmic womb from which the released ancestral gwo-bon-anjs are reclaimed. In combination with Damballah, Ezili guarantees the flow of human generations. Vodou mythology conceives her as the mother of the lwas and of humanity. She is believed to have given birth to the first human beings after Bondye created the world, and since that time her powers of provision have continued to grant children to the human community, a community reliant on Gede's cousin, Zaka, the cosmic lord of agriculture, who is docile, gentle, and kind [10].

Ideologically in Vodou, therefore, as in all other West African and Native American beliefs, the human being and all that is the universe is a manifestation of Bon-dye and its cosmic forces. Within this Spinozaian pantheism, balance, harmony, perfection, and subsistence living with this Being as revealed in nature and it's tilling, cultivation, and husbandry is the modus operandi for human existence. This one good God is an energy force that manifests itself in the human plane of existence via the ancestors and four hundred and one lwa yo (transcendentally real concepts, cosmic forces, and animistic spirits materialized), which humans can access as a material energy force and (ideational) concepts to assist them in being-in-the-world in order to maintain the aforementioned balance, harmony, perfection, and subsistence living of Bondye. Hence, like the God of Judaism, the Good God, Bon-dye Bon, of Vodou is active in history and in current political events, via ancestors, lwa yo, and humans, rather than in the primordial sacred time of myth. Unlike the God of Judaism, however, in Vodou human beings are not distinct, fallen, from that great energy force due to sin and must, therefore, seek to reunite with it by exercising good moral conduct on earth. In the pantheistic worldview of Vodou, the human being, like all other beings, whether sentient or not, are a manifestation of the energy force of Bon-dye. In other words, the human being is a spirit or energy force living in a material body or physical temple. We are constituted energy, which is recycled or reincarnated sixteen times, eight times as a male and eight times as a female, on the planet earth in order to achieve perfection [11]. There is no moral right or wrong in Vodou. "Followers define moral principles for themselves and are guided by life's lessons, the wisdom of ancestors, and communication with spirits" [12]. The aim is the manifestation of the power of Bon-dye amongst the plane of human existence. As such, the energy, which constitutes the human being, is not punished for acts done in the material world through the descent into animal embodiment as highlighted in the reincarnation logic of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. The emphasis in Vodou is on experiencing the lived-world, subsistence living, and perfection. The closer the human being gets to their sixteenth experiences on earth and perfection, the wiser and less materialist they are (which is different from the Protestant ethic which emphasizes material wealth as a sign of god's grace and predestination). At the end of their sixteenth life cycles, once they have embodied and lived out all of the transcendentally real concepts of god, the energy that constitutes the human being is reabsorbed with the original energy force, Bon-dye, the primeval pan-psychic field, which manifested them as life.

In sum, Vodou is a manifestation of the Egyptian/Ethiopian mystery system, les mystere. "The entire hieroglyphic system of Egypt is based upon the symbolic connection which exists between the various beings [of the world] and the cosmic forces, between the beings and the lois [(lwa in Kreyol)] (laws of creation)" [13]. The Vodou belief system posits that Bon-dye, God, is the architect of our universe and its parallel-mirrored world, i.e., (Vilokan, where the forms by which we ought to live are outlined), which was created via geometric laws of creation and cosmic forces. The "laws of creation" create the cosmic forces and other lwa yo in visible manifestations such as the planets, suns, plants, animals, and human beings within geometric spacetime. The Vodou rites are derived from the cosmic forces of the planets and suns created by the geometric laws of creation, which are recreated via the ideological apparatuses, i.e., peristyles, dances, songs, musical instruments, magic and rituals, vévés, alters, etc., of human beings. From the cosmic forces of the planets and suns, plants, animals, and human beings were created within geometric space time. Nature, the ideological apparatuses, i.e., symbols, musical instruments, lakous, peristyles, and ounfo of human beings, and their practical consciousness must correspond to these geometric laws of creation and the cosmic forces.

As such, human beings recreate this creation via the lakous (form of system integration), ounfo, peristyles, vévés, magic and rituals, personal altars (pe) to the cosmic forces and ancestors, herbal medicine, agricultural production, husbandry, and komes, which in total capture that creation and how humans ought to live within it in order to ensure balance and harmony between the noumenal/Vilokan (sacred) world of Vodou and the phenomenal (profane) one of human existence. As Gerdés Fleurant [14] highlights, [t]he primary unit of Vodun social organization is the lakou (compound), and extended family and socioeconomic system whose center is the ounfo (temple), to which is attached the peristyle (the public dancing space). Vodun, a danced religion, acknowledges the unity of the universe in the continuity of Bondye, or God; the Lwa, or mediating spiritual entities; humans, animals; plants; and minerals. Vodun is also a family religion in the sense that its teachings, belief systems, and rituals are transmitted mainly through the structure of the family. It has a sacerdotal hierarchy comprised of the oungan (male) and the manbo (female) and their assistants, the laplas (sword bearer), ounsi kanzo (spouses of the spirits), oungenikon (chorus leader), and ountó (drummers). In the absence of priests, the head of the family, much like a traditional paterfamilias, conducts the service. Most ceremonies take place in the peristyle, whose potomitan (center post) is believed to incarnate ancestral and spiritual forces of family and community. The people dance around the potomitan, which is the point of genesis of essential segments of the ritual process (pgs. 46-47).

The center post or potomitan of the peristyle is the solar support of the community which unites lwa yo, the earth, nature, sun, humans, plants, animals, etc. within one geometric spacetime:

the peristyle forms geometrically the following 1) The mitan, or center-the non-dimensional point; 2) The rectangle, or lengthened square; 3) The circle; 4) The triangle; 5) The straight, horizontal line; 6) The spiral; 7) The curved, horizontal line; 8) The round, vertical line; 9) The square, vertical line; 10) The perfect square; 11) The cross, or intersecting straight lines; 12) The equilateral and the isosceles triangle, formed by the beams which secure the post to the roof [13].

As Leslie G. Desmangles further highlights, The principle of inversion and retrogression is fundamental to Vodou theology as well as to its rituals.... In Vodou the relationship between the cosmic mirror and the profane reality that it represents takes the cosmographic form of the cross. In the cross, Vodouisants see not only the earth's surface as comprehended by the four cardinal points of the universe, but also the intersection of the two world, the profane world as symbolized by the horizontal line, and Vilokan as represented by the vertical line.... The foot of this vertical line "plunges into the waters of the abyss" to the cosmic mirror where the lwas reside; there, in this sacred subtelluric city, is Africa (or Vilokan), the mythical home of Vodouisants, the place of the lwas' origin, and Ginen, the abode of the living dead.... The point at which the two lines intersect is the pivotal "zero-point" [(non-dimensional point)] in the crossing of the two worlds. It is a point of contact at which profane existence, including time, stops, and sacred beings from Vilokan invade the peristil through the body of their possessed devotees (pgs. 104-105).

As such the peristyle, the structure within Vodou rituals and dances are performed, is a mirror reflection and ideological constitution of the universe and all of its forces from the moment of creation to the presence:

The four poles sustaining the structure symbolize mythologically the four cardinal points of the universe, covered by an overarching roof that represents the cosmic vault above the earth. Like the horizontal lines of the cross, the floor of the peristil symbolizes the profane world, while the vertical pole (potomitan) in the center of the peristil represents the axis mundi, the avenue of communication between the two worlds. Although the downward reach of the potomitan appears to be limited by the peristil's floor, mythologically its foot is conceived to plunge into Vilokan, the cosmic mirror. The point at which the potomitan enters the peristil's floor symbolizes the zero-point. During the ceremonies, the potomitan becomes charged with or "polluted" by the power of the lwas. Hence, before tracing the geometrical symbols of the lwas (vévés), the oungan or mambo may touch the pole, a ritual act that empowers him or her to summon the lwas into the peristil. Thereafter, like the potomitan, the oungan's (or mambo's) body becomes in itself the source of power, a repetition of the microcosmic symbol, a moving embodiment of the vertical axis around which the universe revolves [10].

Within the knowledge and functions of the cosmic forces and the geometric laws of creation oungan yo (priests), manbo yo (priestesses), bokor yo (sorcerers), and gangan yo/dokté féy (doctors of herbal medicine), the power elites of Vodou, can access lwa yo (animistic and cosmic spirits or forces) for wealth, healing, luck, etc. in a community based on living in harmony with nature and its laws and products of creation, which is expressed through music, dance, husbandry, tilling and cultivating the land (for medicinal and agricultural purposes), and komes for human sustenance and well-being. The rites and ceremonies of Vodou, "which can be seen as the reliving of the first act of creation when Bondye fashioned the world," ensure the delicate balance and harmony between Bon-dye, the cosmic forces, the geometric laws of creation, and human actions [10]. Within the physics and metaphysics of this Vodou system a distinct epistemology, Haitian transcendental idealism and realism, emerged.

Haitian Epistemology and Haitian Idealism

For Mocombe, an authentic Haitian epistemology emerges out of the ever-increasing demystification, demythologization, rationalization, and institutionalization (enchantment of the world) of the physical world around this spiritual belief system, Vilokan/Vodou, of the African people of Haiti highlighted above. The Haitian Epistemological position that would emerge out of the ontological worldview of the African people of Haiti and their form of system and social integration is a form of Kantian transcendental idealism and realism, which would be institutionalized throughout the provinces and mountains of the island [1,6]. It (Haitian epistemological transcendental idealism) is both responsible for the epistemological anarchy of the profane (transcendentally ideal) phenomenal (material) world, and the sacred (universal-ideational, but transcendentally real) noumenal (Vilokanic) world of Vodou mysteries.

Kantian transcendental idealism "attempts to combine empirical realism, preserving the ordinary independence and reality of objects of the world, with transcendental idealism, which allows that in some sense the objects have their ordinary properties (their causal powers, and their spatial and temporal position) only because our minds are so structured that these are the categories we impose upon the manifold of experience" [15]. Haitian epistemological transcendental idealism and realism, Haitian Idealism or Vilokan Idealism, is a form of transcendental idealism in the Kantian sense in that it attempts to synthesize empiricism and idealism (rationalism) via synthetic a priori concepts/ideals, supplemented with trances, dream-states, and extrasensory perceptions, the Haitians believe can be applied not only to the phenomenal but also the noumenal (Vilokanic) world in order to ascertain the latter's (transcendentally real) absolute knowledges they call, lwa, gods/goddesses (401 concepts, ideas, and ideals represented as gods/goddesses), of Vilokan/Vodou. So like Kant, Haitian epistemological transcendental idealism, holds on to analytic truths, truths of reasons or definitions, as outlined in their proverbs (pwoveb); a posteriori truth, truths of experience or experiments, also embedded in their proverbs, geometry (veves), and herbal medicine; and synthetic a priori concepts (categories in Kantian epistemology supplemented with trances, dream-states, extrasensory perceptions, etc.), truths stemming from the form of the understanding and sensibility of the mind and apparatuses of experience embedded not only in their proverbs but their Vodou rituals, beliefs, and magics, which suggests that trances, dream-states, and extrasensory perceptions allow access to things as they are in themselves. The latter (trances, dream-states, extrasensory perceptions), in other words, are also categories of the understanding they believe can be applied to the noumenal or Vilokanic world in order to know gods/goddesses, lwa yo, which are transcendentally real immutable/absolute concepts, ideas, and ideals God has created and imposed upon and in the material world, from the mirrored world of the earth (Vilokan), which the people, who embody these concepts, ideas, and ideals, should utilize to recursively reorganize and reproduce their being-in-and-as-the-world in order to achieve perfection over sixteen life cycles [10,11]. Hence, unlike Kantian idealism, which removes God out of the equation via the categories, which imposes the order we see in the phenomenal world, Haitian epistemological transcendental idealism and realism, Haitian/Vilokan Idealism, holds on to the concept of God, supernatural, and the paranormal to continue to make sense of the plural tensions between the natural (material) world, i.e., the world of phenomenon, as our minds and senses structure our experiences of it, and the world as such, ideational, noumena, i.e., the supernatural and paranormal world of Vilokan, which is knowable as truth-claims, knowledge, and beliefs, through dreams, divinations, revelations, extrasensory perceptions, experience, reason and rationality, and the synthetic a priori's of Kant, for pure (development of science, i.e., herbal medicine, etc.) and practical reason (i.e., morals and values). Thus Haitian/Vilokan Idealism, unlike Kantian Transcendental Idealism, implies that the transcendentally real objects, concepts, ideals, ideas, etc., of the (ideational) noumenal world are absolute and real, and the form of sensibilities and understandings, which include dream states, divinations, and extrasensory perceptions are other categories, which can be applied beyond the phenomenal world, where the objects are really subjective ideas, in order to ascertain the nature of the absolute concepts of the Vilokanic/noumenal world, emanating from God's mind, in order to achieve balance and harmony with it in the phenomenal (See Table 1). Hence, unlike Kantian idealism, which removes God out of the equation via the categories, which allows that in some sense the objects of the empirical world have their ordinary properties (their causal powers, and their spatial and temporal position) from the human mind and form of sensibilities, Haitian epistemological transcendental idealism and realism, Haitian/Vilokan Idealism, holds on to the concept of God, supernatural, and the paranormal to continue to make sense of the plural tensions between the natural (profane) world, i.e., the world of phenomenon, and the world as such, noumena, i.e., the supernatural and paranormal world of Vilokan which is knowable as truth-claims, knowledge, and beliefs, through divinations, dreams, extrasensory perceptions, experience, reason and rationality, and the synthetic a priori, for pure (development of science, i.e., herbal medicine, etc.) and practical reason (i.e., morals and values).

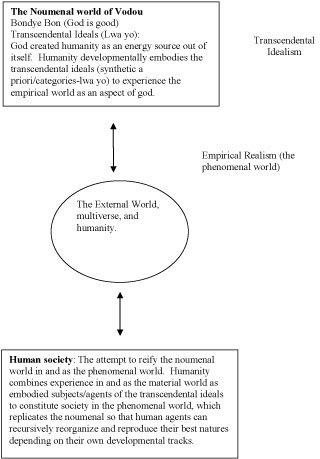

Within this pantheistic (Spinozaian) conception of the multiverse and material world, knowledge, truth-claims, and beliefs arise from the transcendentally real objects and concepts (lwa yo) of bondye/God as embedded in the earth's mirrored world (Vilokan) and gets deposited in our nanm (souls) intuitively, in dreams, extrasensory perceptions, divinations, sorcery, reason, rituals, and or experiences which in turn constitutes and structures the form of the understanding of our minds and bodies (senses) so that we can experience the material world according to our developmental track over sixteen reincarnated life cycles [1,5,6,11]. The human being internalize and recursively (re) organize and reproduce these transcendentally real concepts as their practical consciousness in the phenomenal (subjective) material world not always in their absolute (ideational) forms as defined noumenally (the sacred mirrored world of Vilokan), but according to their level of learning, development, capacity for knowledge, methods, and modality, i.e., the way they know more profoundly-kinesthetically, visually, etc., once they are aggregated or embodied as a person See Figure 1.

As defined, Haitian epistemology is an epistemological transcendental idealism and realism, Haitian Idealism or Vilokan Idealism, that posits that both phenomenon (the profane world) and noumenon (its mirror image where wisdom, ideals, concepts, and ancestors reside) are knowable through dreams, sorcery, divinations, experience, and the form of human sensibility and understanding (reason), which stems from the energy force of a God, and used to recursively (re)organize and reproduce their being-in-and-as-the-world. Ontologically speaking, in other words, within the Haitian metaphysical worldview, Vilokan/Vodou, the world is a unitary (energy) material world created out of Bondye. The world is a creation of a good God, Bondye Bon, which created the world and humanity out of itself composed of two intersecting spheres, the profane (the phenomenal world) and sacred (noumenal/Vilokanic, mirrored world of the profane). Embedded in that pantheistic material world are concepts, transcendentally real ideals, lwa yo in Haitian metaphysics, from the parallel mirrored (Vilokanic) world, that humanity can ascertain via dreams, divinations, extrasensory perceptions, experience, and the structure of its being, form of understanding and sensibility, to help make sense of their experience and live in the world, which is Bondye, and therefore sacred, as they seek perfection and reunification (reintegration) with God the energy force/source.

That is to say, it, Bondye, provided humanity with transcendentally real objects, concepts, ideas, ideals, and practices, i.e., lwa of Vodou, proverbs, rituals, dance, knowledge of herbal medicine, trades, and skills, by which they ought to know, interpret, and make sense of the (transcendentally ideal) external (phenomenal profane subjective) geometric/cosmic world and live in it comfortably. These transcendentally real objects, concepts, ideas, ideals, and practices can be known through dreams, sorcery, divinations, experience, or rationality, and becomes the structure (categories) through which humanity come to know, hold beliefs and truth-claims, which emanate from the noumenal world. So Bondye, a powerful energy force that always existed created the world and humanity out of itself. Humanity and the world around it are an aggregation of bondye's material energy, the energy of God, which constitutes its existence. In humanity this existence is composed of three distinct aggregations of energy (ti bon anj; gwo bon anj; ko, the body), all of which are material stuff, which constitute our nanm (souls) where personality, truth-claims, knowledge, and beliefs are deposited, via experience, reason, the energy source of a God as manifested via a lwa (in dreams, rituals, divinations, sorcery, trances, extrasensory perceptions, etc.), and can be examined and explored as the synthetic a priori, categories, of the human agent, which allows them to experience the material world.

For humanity to constitute its existence and be in the world according to the will of God or Bondye, in other words, objects and concepts, transcendentally real ideals, lwa yo, stemming from God's will (the mirrored world of the profane, Vilokan) are embedded in the material world, which is God, and can be ascertain and embodied by humanity via their constituted being as a material being with extrasensory perceptions, reason and rationality, and or through experience. As these concepts are ascertain, they are constituted and institutionalized, and passed on through humanity via priests and early ancestors who institutionalized (reify) them in the natural world via religious ceremonies, dance, symbols, rituals, herbal medicine, trades, concepts, and proverbs. These trades, ideals, dance, rituals, proverbs, and or concepts are truisms, mechanisms to ascertain and constitute knowledge, which although they are deduced from the constituted make-up (categories) of the human being, in Haitian metaphysics they are attributed to God and the ancestors who institutionalized (reified) them in order to be applied in the material world so that their descendants can live freely in the world, satisfy their needs, be happy, and achieve perfection in order to reunite with God after their sixteen life cycles [5,6,8,11].

Hence Haitian epistemological transcendental idealism and realism (Haitian Idealism, Vilokanism, Vodouism, or Vilokan Idealism) is not only natural, but supernatural and paranormal to the extent that it supplements the synthetic a priori concepts Kant attributes to the categories of the mind with divinations, revelations, dream states, and extrasensory perceptions in order to ascertain the (transcendentally real) absolute concepts, ideals, ideas, etc., (lwa) of God as embedded in the noumenal (Vilokanic) world, which can be internalized by the human subject as their practical consciousness over sixteen cycles of births and rebirths after which they reintegrate into Bondye where their essence can become concepts, ideas, and ideals as in the case of Oungan Jean-Jacques Dessalines (the father of the Haitian nation) who, as the embodiment of the lwa Ogou Feray, concept of Political warrior, became a lwa following his death [11]. (See Figure 1). Moreover, it posits that these absolute lwa yo, concepts, ideas, ideals, etc., are part of the noumenal world (sacred world of Vilokan), which is not a plural world as plurality and relativity belongs to the world of phenomenon, and can eventually be known by extrasensory perceptions, human reason, understanding, and experience (supplemented categories to the Kantian categories). However, in the human sphere the (transcendentally ideal) world of phenomenon and its plurality is a result of the different levels of development (reason, experience, capacity, and modality) of the human subjects (not all humans develop their form of sensibilities and understanding at the same rate or in the same life cycle). Albeit humanity is reincarnated until they have ascertained all of the true concepts of the unitary world, which can be done so through experience and a priori, and will seize to exist (will seize to experience reincarnation) once they do so.

So on top of the twelve Kantian schematized categories of the understanding, divided into four groups of three (1. The axioms of intuition, i.e., unity, plurality, and totality; 2. The anticipations of perception, i.e., reality, limitation, and negation; 3. The postulates of empirical thought, i.e., necessary, actual, and possible; 4. The analogies, i.e., substance, cause, and reciprocity), necessary for experience by making objective space and time possible, Vilokanic/Haitian idealism adds dream states, trances, and extrasensory perceptions as a fifth group of three to make known the concepts, lwa yo, of the Vilokanic world knowable so that human actors can achieve balance between the phenomenal world and the former (Vilokanic/noumenal).

Thus, for Kant experience requires both the senses, the a priori forms of sensibility, i.e., space and time, and the understanding, i.e. the twelve categories. A unified consciousness (not a self or the Cartesian "I"), which is a structural feature of experience necessary to provide the unity to our experience, what Kant calls, "the transcendental unity of apperception," rule-governed and connected by the categories, experiences real objects that we perceive and exist independently of our perception of them. Thus the spatio-temporal objects are necessarily relative to and subject to the a priori forms of experience, i.e., forms of sensibility and the understanding. In this sense, Kant does away with the noumenal world of absolutes, which is unknowable as the independent objects are phenomenal, relative to the a priori forms of experience. Unlike Kant, however, Haitian Idealism posits that the nanm, soul, constituted by its three structures, which provides unity to our experiences, is a material thing, a Cartesian I composed of three distinct entities, ti bon anj, gwo bon anj, and ko, (sometimes four, lwa met tet, as in Haitian metaphysics a serviteur of Vodou may have a fourth consciousness that directs it in its decision-making) that are also tied to the natural and noumenal world and can be manipulated in life as well as death. On top of it's a priori forms of sensibility and Kantian categories are dream-states, trances, and extrasensory perceptions, which allows the nanm to have access to the world of Vilokan/noumenal world where we can perceive the things that are phenomenal, relative to our a priori forms of experience, as they are in-themselves in order to achieve balance between the world as it appears to us and how it ought to be so that we can live happily, abundantly, and free.

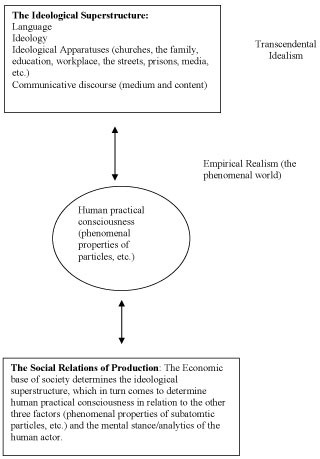

Haitian/Vilokam Idealism as such indicates a condition of absolute on the one hand as it pertains to the Vilokanic or noumenal world; and relativity in our notions of objects and reality on the other as it pertains to the phenomenal world. In terms of the latter, the phenomenal world, in other words, is simply the world of plurality constituted by imperfect beings, anti-dialectically (constantly fighting against the praxis of others for their own understanding), living through their aggregated material bodies and imperfections. This is why, epistemologically speaking, the phenomenal world in Haiti, resembles an epistemological anarchic world where everyone exists for their own liberty and existence according to their own developmental track, capacities, modalities, methods, and belief systems governed by an eye for an eye normative worldview, which prevents others from encroaching on an individual's (regardless of their level of development) right to exist. Out of this libertarian phenomenal world of plurality enframed by the absolute Vilokanic/noumenal, the concepts of liberty and equality (libertarianism and egalitarianism) would arise, drive the Haitian Revolution, and constitute Haitian identity and society in the mountains and provinces of the country via their form of system and social integration, i.e., the lakou system and the Vodou Ethic and the spirit of communism, respectively. Moreover, in keeping with Firmin's logic of highlighting black people's contributions to the universality of science, the argument posited here is that it is the metaphysics, ontology, physics, sociology, and epistemology of this Haitian transcendental idealism and realism as revealed in contemporary quantum and social theorizing, and not any racial essentialism or reactionary logics of oppression, that forms the basis for African people's contributions to the social sciences and social theory. Paul C. Mocombe's phenomenological structural theory and methodology, which attempts to resolve the structure/agency problematic of the social sciences, better captures this universal process over Afrocentricity, noirisme, black modernity, "double consciousness," etc. (See Figure 2).

Conclusions: Phenomenological Structuralism

In keeping with the universal project of Firmin and highlighting African people's contribution to the social sciences, at the base of Paul C. Mocombe's social scientific theory, phenomenological structuralism, is Haitian epistemology, Haitian/Vilokan idealism, and not racial essentialism or reactionary theories of oppression. In experiencing the world, African people developed universal scientific concepts that the West would develop and omit. For Mocombe, the parallels and omissions in the original sciences of African people, and not race or theories of oppression, are keys to further developing the sciences and understanding African people's contributions to that project. Unlike German Idealism whose intellectual development from Kant to Schopenhauer, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Husserl, Heidegger, and the Frankfurt school produced the dialectic, Marxist materialism, Nietzscheian antidialectics, phenomenology, and deontological ethics. According to Mocombe [1,6], Haitian epistemology, Haitian/Vilokan Idealism, produces a hermeneutical phenomenology, materialism, and an antidialectical process to history enframed by a reciprocal justice as its normative ethics. The latter, antidialectic, is an approach to the historical process constantly being invoked by individual social actors to reconcile the parallel worlds of creation assumed in Haitian ontology and epistemology: the noumenal (sacred-ideational world of Vilokan) and phenomenal (profane-material world) subjective world in order to maintain balance and harmony between the two so that the human actor can live freely and happy with all of being without distinctions or masters. As such, Haitian epistemology as a form of transcendental realism and idealism, Haitian/Vilokan idealism, is phenomenological, in the Heideggerian sense (i.e., hermeneutical), material in the Marxian sense, and antidialectical. It refutes Hegel's claims for the importance of historical formations and other people (social formations) to the development of self-consciousness. Instead, Haitian/Vilokan idealism, phenomenologically, is an antihumanist philosophy that emphasizes the things in the consciousness (lwa or concepts, ideas, ideals) of the individual as they stem from the noumenal/Vilokanic world, and get interpreted according to their level of learning, development, capacity for knowledge, methods, and modality, i.e., the way they know more profoundly-kinesthetically, visually, etc., as they antidialectically and relationally seek to reproduce them in the phenomenal world as their practical consciousness against other interpretive formations of these same concepts in the material world as recursively organized and reproduced by others.

So what does Haitian/Vilokan Idealism, its metaphysics, phenomenology, materialism, sociology, antidialectics, antihumanism, and reciprocal justice, has to say to modern science, both physical and social, in terms of the development of a theory and methodology. For Mocombe it is the materialist holism of Haitian idealism, which attempts to connect cosmology, cosmogony, social relations, the phenomenology of subjective experience, and the process of antidialectics, which is important. For they offer a new conception of human agency, which is tied to physics, phenomenology, and human social relations, that is relevant for the social sciences and its ongoing debate to resolve its structure/agency problematic. That is, Haitian/Vilokan idealism is tied to a materialist holism that directs human social action, via its antidialectical historical process, towards the transcendentally real ideational concepts, lwa yo, of the natural and supernatural world above social constructive identifications, which, as subjective positions, attempt to limit human phenomenological agency as it experiences being-in-the-world. In this vision, it offers, through the concept and process of antidialectics, antihumanism, and phenomenology, an agential theory of social action that is relevant for the construction of a social theory and methodology for the social sciences that is scientifically universal, antiracially essential, and non-reactionary to white supremacy.

It is the materialism, physics, and metaphysics of Haitian/Vilokan idealism, its antihumanism, phenomenology, and antidialectical viewpoint of Haitian social practice, which Mocombe attempts to tie to quantum mechanics and the phenomenology of German idealism that it parallels in his structurationist theory and methodology, i.e., phenomenological structuralism. Hence what Mocombe is suggesting in phenomenological structuralism, which seeks to highlight the phenomenology of being-in-the-structure-of-those-who-control-a-material-resource-framework and the origins of our practical consciousness vis-à-vis our aggregation as subatomic/chemical particles, is that embodiment is the objectification of the transcendental ego (See Figure 2). This transcendental ego is a part of an universal élan vital, the superverses and multiverses, that has ontological status in dimensions existing at the subatomic particle level and gets embodied via, and as, the body and connectum of Being's brains. Hence, as highlighted in Haitian metaphysics, the transcendental ego, nanm, is the universal élan vital, which is the neuronal energies of past, present, and future Beings-of-the-multiverse, embodied, and encounters a material world via and as the body and brain in mode of production, language, ideology, ideological apparatuses, and communicative discourse. Once embodied in and as human individual consciousnesses in a particular universe, world, and historical social formation, the transcendental ego, nanm in Haitian metaphysics, becomes an embodied hermeneutic structure that never encounters the world and the things of the world in themselves via the aggregated built in ontogenetics' of the body, brain, and the neuronal energies. Instead embodied hermeneutic individual consciousness is constituted via recycled/entangled/superimposed subatomic neuronal particle energies which are aggregated as a transcendental ego and the body in their encounter and interpretation of past recycled/entangled/superimposed neuronal memories and things enframed in and by the language, bodies, ideology, ideological apparatuses, communicative discourse, and practices (social class language game) of those who control the economic conditions of an aggregated material resource framework and its social relations of production. In consciousness, as phenomenology posits, it (individual subjective consciousness of embodied beings) can either choose to accept the structural knowledge, differentiation, and practices of, the (chemical, biological, and physiological) drives of the body, the impulses (phenomenal properties) of psychionic recycled/entangled/superimposed past consciousnesses of subatomic neuronal particles, the actions of those who control, via their bodies, mode of production, language, ideology, ideological apparatuses, and communicative discourse, the economic conditions of the material resource framework and recursively reorganize and reproduce them in their practices, or reject them, through the deferment of meaning in ego-centered communicative discourse, for an indeterminate amount of action-theoretic ways-of-being-in-the-world-with-others, which they may assume at the threat to their ontological security. It is Being's (mental) stance or analytic, ready-to-hand, unready-to-hand, and present-at-hand vis-à-vis 1) The ontogenetic (chemical, biological, physiological, etc.) chemical drives and forms of sensibilities and understanding of the aggregated body and brain, 2) Impulses, phenomenal properties, of residual actions/memories of embodied recycled/entangled/superimposed past consciousnesses/subatomic particles, 3) The phenomenological meditation/deferment that occurs on the latter actions, and ideologies of a social system along 4) With its dialectically determined differentiating logic, which produces the variability of actions and practices in, and as, cultures, social structures, or social systems that enframe the material world. In the end, however, 5) Power and power relations of those who internalize the structural reproduction and differentiation, stemming from the mode of production, of the social structure as their practical consciousness, as well as the antidialectical disposition of those who do not, determine what alternative actions are allowed to manifest in the world (See Figure 2.).

So to the end of fixing structurationism to account for the nature and origins of alternative practical consciousnesses outside the structural reproduction and differentiation of capitalist relations of production in modernity, Paul C. Mocombe's [1,5] phenomenological structuralism builds on the material relationship highlighted in physics between the identity and indeterminate behavior of subatomic particles highlighted in quantum mechanics (the notions of superposition and quantum entanglement) and the determinate behavior of atomic particles in their aggregation as highlighted in general relativity to understand the material constitution of consciousness at the subatomic/neuronal level in, and as, the brain. And it's (consciousnesses') unfolding and manifestation as human practical consciousness at the atomic level as revealed by language, ideologies, ideological apparatuses, communicative discourse, and the actions of the bodies (i.e., practical consciousness) of those who control a material resource framework, and the mode of distributing its resources, where a society is constituted and ensconced. So borrowing from Haitian/Vilokan Idealism, this interconnectedness between the world of phenomenon and noumenon and the human being as a material subject whose nanm is a material thing capable of constructing their own phenomenological experiences, Mocombe begins his analysis by demonstrating the connection between the noumenal world of contemporary quantum mechanics and the phenomenal world of subject aggregation and constitution where the Haitian concepts of antidialectics and phenomenology as it parallels the hermeneutical phenomenology of Heidegger serves as a mechanism for agential initiative within and against social reproduction and differentiation, which is simply the reification of an adverse subjective experience, which attempts to curtail the human actors' full connection to the noumenal world.

Mocombe's project as such continues the universal construction of the social sciences, which Firmin began with anthropology, by neither reifying a black psychology to account for the African contribution, a la noirisme and Afrocentricity, nor a reactionary theory of oppression as found in Du Boisian "double consciousness," for example. Instead, he builds on the Firminian "human" essentialist and universal conception that African people are no different from whites and possess the same intellectual capacities by emphasizing the scientific nature of their Vodou science and tying it to the scientific project of the West to develop his theory of phenomenological structuralism.

References

- Mocombe Paul C (2018b) Mind, body, and consciousness in society: Thinking vygotsky via chomsky. Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

- Nicholls David (1979) From dessalines to duvalier: Race, colour and national independence in haiti. Rutgers University Press, New Jersey.

- Firmin, Joseph-Antenor (2002) The Equality of the Human Races (Asselin Charles, Trans.). University of Illinois Press, Chicago.

- Du Bois Laurent (2012) Haiti: The Aftershocks of History. Metropolitan Books, New York.

- Mocombe Paul C (2016) The Vodou Ethic and the Spirit of Communism: The Practical Consciousness of the African People of Haiti. University Press of America, Maryland.

- Mocombe Paul C (2017a) The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism; and the vodou ethic and the spirit of communism. Sociology 51: 76-90.

- Mocombe Paul C (2017b) Phenomenological structuralism: A structurationist theory of human action. Sociology International Journal.

- Mocombe Paul C (2018a) Haitian/Vilokan idealism versus german idealism. Cross currents: An International Peer-Reviewed Journal on Humanities & Social Sciences 4: 69-74.

- Mocombe Paul C (2019) The Theory of Phenomenological Structuralism. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

- Desmangles Leslie G (1992) The Faces of the Gods: Vodou and Roman Catholicism in Haiti. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

- Beauvoir, Max (2006) Herbs and Energy: The holistic medical system of the haitian people. In: Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick, Claudine Michel, Haitian Vodou: Spirit, Myth, & Reality. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana.

- Michel, Claudine (2006) Of worlds seen and unseen: The educational character of haitian vodou. In: Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick, Claudine Michel, Haitian Vodou: Spirit, Myth, & Reality. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana.

- Rigaud Milo (1985) Secrets of Voodoo. City Lights Books, San Francisco, California.

- Fleurant Gerdes (2006) Vodun, Music, and Society in Haiti: Affirmation and Identity. In: Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick, Claudine Michel, Haitian Vodou: Spirit, Myth, & Reality. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana.

- Blackburn Simon (2008) Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Corresponding Author

Paul C Mocombe, Department of Philosophy and Sociology, West Virginia State University, Institute, West Virginia, The Mocombeian Foundation, Inc, USA.

Copyright

© 2019 Mocombe PC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.