Assessment of the Quality of Information on Adrenal Surgery Available on the Internet

Abstract

Background: The internet has become an important source of health-related information [1-3]. However, concerns exist regarding the lack of regulation, quality, accuracy, and reliability of some sources of medical information, particularly in the case of social media [4-6]. Studies have attempted to analyse the quality of information available on arange of healthcare related topics across various specialities [7-15]. To the authors' knowledge, no study has addressed the question in relation to adrenal surgery.

Methods: This study aimed to assess the information available on adrenalectomy on the first 20 websites returned by the 3 most popular search engines in Europe. Each site was categorized by type and assessed for content quality using the DISCERN score [16], the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) benchmark criteria [4], and an adrenalectomy specific content score.

Results: The quality of information on adrenalectomy available online is variable. The majority of websites were affiliated with hospital trusts or non - profit organisations, with only one commercial website being identified. However, several websites had not been recently updated and some failed to provide basic information on the benefits and risks of the procedure. A number of links led to academic papers, which were targeted at clinicians and did not provide patient specific information. The mean discern scores were similar across all groups, whereas Hospital trust associated, non-profit associated, physician and academic websites achieved the highest content scores.

Conclusion: This study highlights the for need reliable and contemporaryon-line information for patients undergoing adrenal surgery.

Keywords

Adrenalectomy, Adrenal disorders, Adrenal surgery, Patient information, Online information

Introduction

In the last two decades, the internet has gained increasing influence on how information is accessed in the health care setting. Many patients, particularly young adults, resort to the internet as their source of health related information [1-3,7-19]. Studies have also demonstrated that patients may trust online information more that obtained from their doctor or may not retain all the information discussed at the time of consultation with their doctor [3]. Having access to quality information online therefore, is paramount to patients understanding of their condition, its management and also to help inform the informed consent process. From a clinicians' perspective, it is important to be aware of the resources available and their quality, to enable us to advise patients with regard to accessing quality medial information from reliable resources as adjuncts to the information imparted at the time of consultation.

Adrenalectomy is a complex surgical procedure performed for a number of adrenal conditions. It is predominantly carried out in high volume, specialist centres. However, we are not aware of any study published to date that determined the quality of information available to patients pertaining to adrenalectomy on the internet. The aim of this study, therefore, was to assess the quality of information on adrenalectomy available on the Internet using recognized scoring systems, identification of quality markers, and a novel specific score. Scoring systems utilised in this study included the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) benchmark criteria and DISCERN criteria [4-16].

Methods

Searching on the Web

Using the keyword “Adrenalectomy” as the search term, independent searches were conducted on the three most popular search engines: Google, Bing and Yahoo!. Google is the dominant global search engine, composing 92.05% of the total market share, followed by Bing (2.83%) and Yahoo! (3.36%) (Figures as of August 2020) [20]. The first 20 websites encountered after conducting a search on each of the websites were reviewed. Searches were performed in April 2020. Twenty three duplicate websites, three that were inaccessible and three that were not deemed relevant were excluded from analysis. The 31 resultant sites were included for analysis.

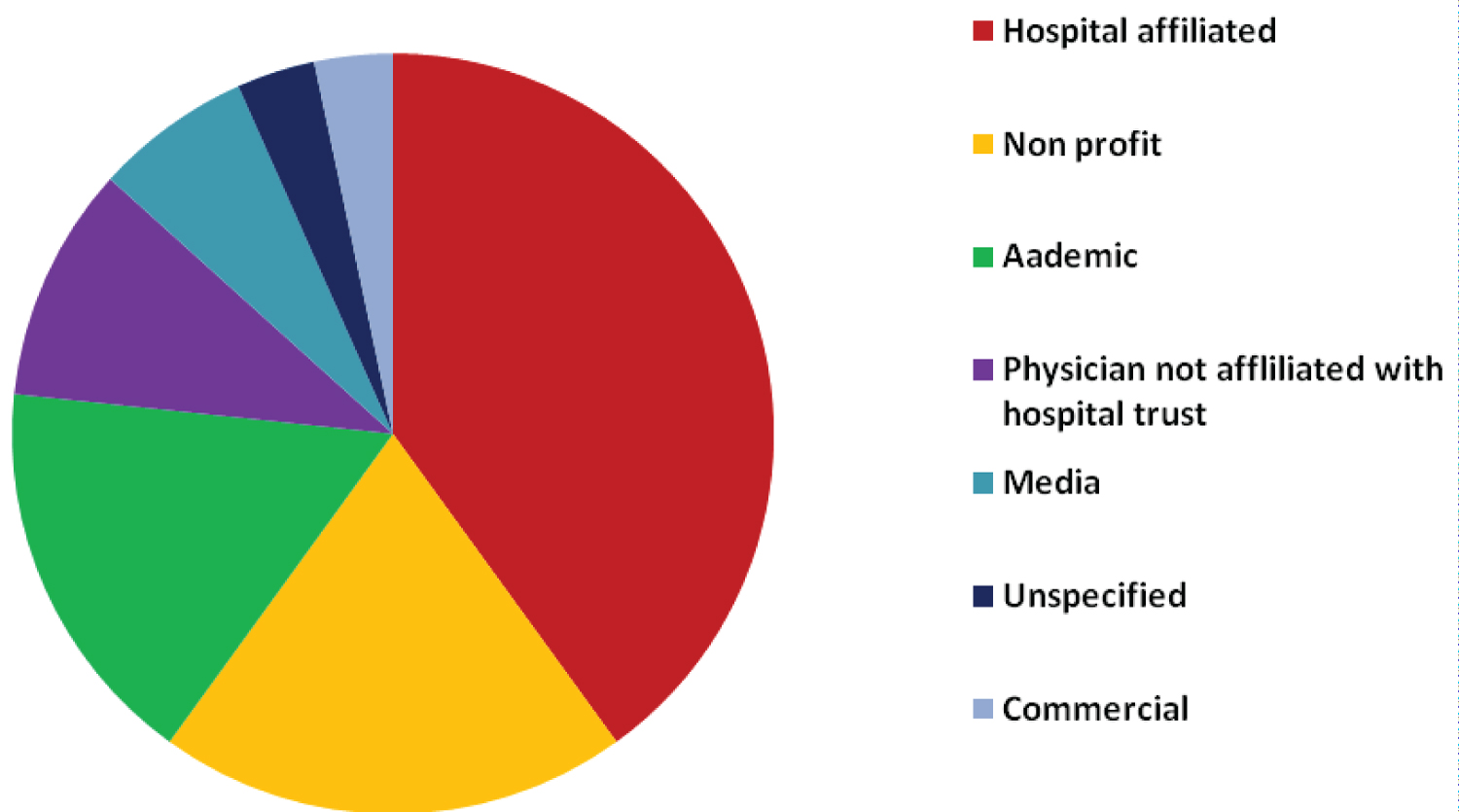

The resultant websites were classified first based on website type. Sites were classified as associated with healthcare institutions, academic, commercial, media, non-profit/ discussion groups and unspecified. Those associated with healthcare institutions were associated with a medical society or hospital trust. Academic websites included those affiliated with a university and included published literature. Websites were considered commercial if they displayed advertisements or included products for sale. Physician websites included professional sites for individual physicians or groups not affiliated with an academic institution. Media websites were non-medical social media sites such as YouTube or Facebook. Any website which did not fit into any of these categories was classed as unspecified.

Assessing content quality

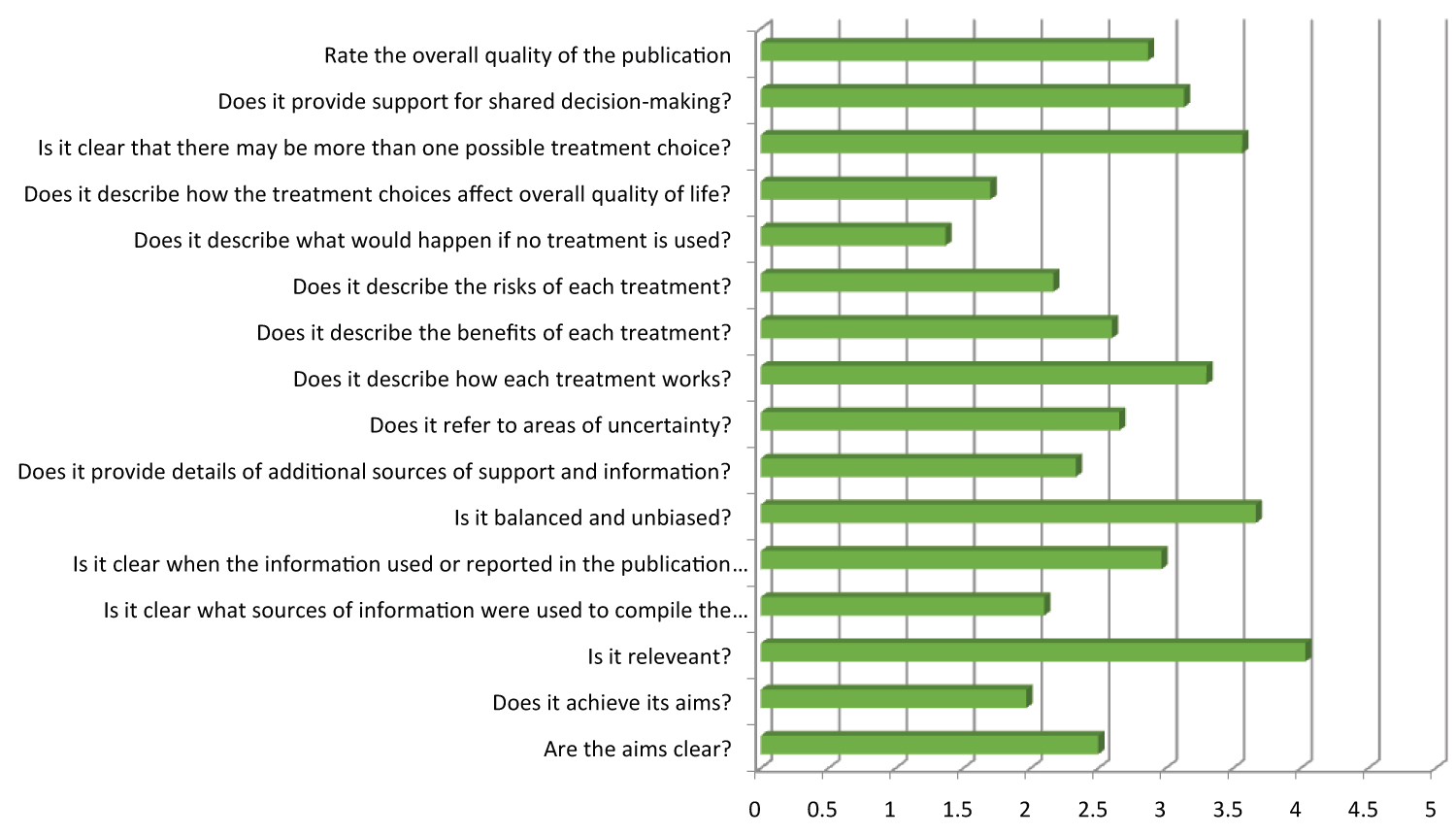

Websites were then assessed for quality and validity using the DISCERN score, the JAMA benchmark criteria, and an adrenalectomy specific content score (Table 1).

DISCERN, developed by an expert group in the United Kingdom, is an instrument designed to judge the quality of written consumer health information about treatment choices for a health problem. It determines the quality of a publication based on 16 questions. The first 8 questions concern the reliability of the publication, and the subsequent 7 questions address specific details of the information about treatment choices. The last question is an overall quality rating of the website. A score of one is allocated in the case of serious or extensive shortcomings. Each question can receive a score of between 1 and 5. A score of 3 indicates potentially but not serious shortcomings. A score of 5 is given where there are minimal shortcomings.

Secondly, the JAMA benchmark criteria were utilised. This represents a four point score aiming to assess authorship, attribution, disclosure, and currency [4]. The authorship criterion requires that the website provide details of authors and contributors, their affiliations, and relevant credentials. Attribution entails listing references and sources for all content and indicating any relevant copyright information. Currency refers to the provision of the dates that content was posted and updated, and disclosure requires that website ownership be prominently and fully disclosed, along with any sponsorship, advertising policies, and potential conflicts of interest.

To assess the informational value, comprehensiveness and accuracy of each website in more detail, an adrenalectomy specific content score was compiled, comprising 25 factors (Table 1). This was done in consultation with adrenalectomy trained consultants and by referencing current peer-reviewed literature. It was based on previously published content scores [21] where one point was allocated for the mention of each of the predefined terms that related to general characteristics of the condition, treatment options, and complications. Sites were then scored from 0 to 25, with 25 indicating a site of optimum quality.

Finally, websites were reviewed for display the Health on the Net (HON) Certificate. The Health On Net foundation is an internationally recognised organisation established in the 1990s, that provides a code of conduct for websites that agree to a set of principles [22]. The 8 principles are authoritative (indicate the qualifications of the authors), complementary (information should support, not replace, the doctor-patient relationship), privacy (respect the privacy and confidentiality of personal data submitted to the site by the visitor), attribution (cite the source(s) of published information, date medical and health pages), justifiability (site back up claims relating to benefits and performance), transparency (accessible presentation, accurate email contact), financial disclosure (identify funding sources) and advertising policy (clearly distinguish advertising from editorial content).

Results

A total of 31 websites were included for analysis (Table 2). Figure 1 shows the breakdown according to website type. The majority were associated with healthcare institutions. The mean overall scores by website type are illustrated in Figure 2.

DISCERN scores

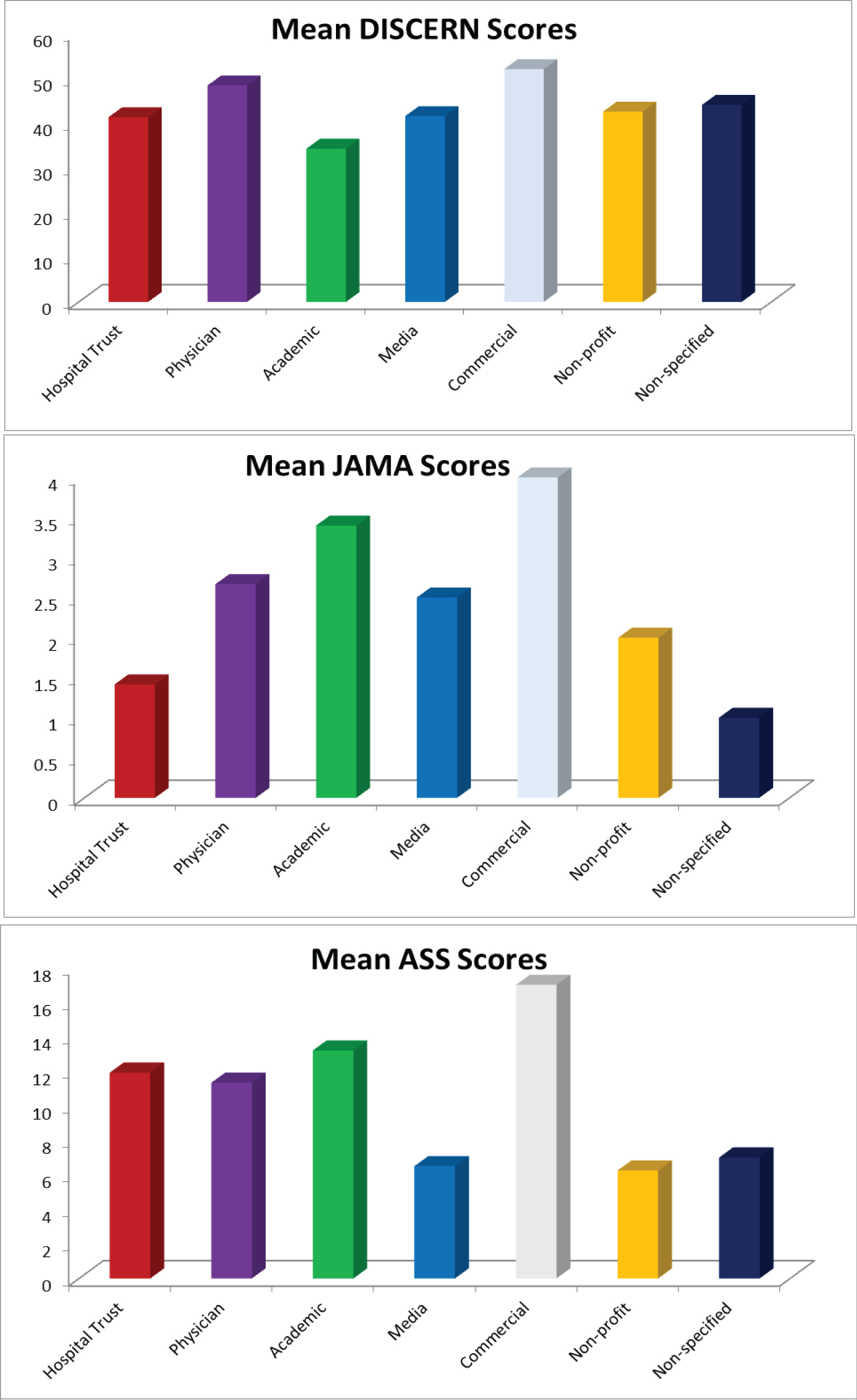

The highest-scoring website was a non- profit website with a score of 68. Eleven websites (36.7%) were scored as being of poor quality, with serious or extensive shortcomings. Only 4 sites attained scores greater than 60, representing excellent quality with minimal shortcomings. The mean DISCERN score for all websites included in the analysis was 43.1 (range 21-68). The combined rating score per DISCERN item is depicted in Figure 2.

The mean overall DISCERN scores by website type are depicted in Figure 3. The overall highest mean DISCERN was scored by a commercial website (Table 3). However, it should be noted that only one website of this category was included in this analysis, which may have influenced this result.

JAMA benchmark criteria

The mean JAMA benchmark criteria score for all websites was 2.2. Five sites had the maximum score of 4, 3 of which were academic papers, and therefore required to display date of publication and authors. There was a significant difference between the groups (range of 1-4), with the commercial and academic sites scoring highest mean scores.

Adrenalectomy specific content score

The highest content score was 22, obtained by one non-profit site and one website associated with a hospital trust. One website, of the hospital-affiliated type, received only one point. The mean overall score for all groups was 11.3. Overall, the one commercial website included in the analysis had the highest mean score of 17, followed closely by hospital-associated and physician-type websites, with a means of 11.9 and11.3 respectively.

HON certification

None of the analysed websites analysed appeared to display the HON certification.

Discussion

The widespread availability of internet disseminated information in current times is both an advantage and a concern in the setting of healthcare. While on the one hand it allows patients access to information in their own time to supplement that provided by their clinicians, on the other, it allows virtually unregulated publication of information that is easily accessible on a broad scale. A challenge exists therefore, to find credible information, based on best available scientific evidence, rather than anecdotal or opinion-based articles which could potentially contain misleading information. The aim of this study was to determine the nature of information on adrenalectomy on the internet using previously published and validated measures of quality.

The findings of this study indicate that the websites likely to be easily accessed by patients in Europe using three popular search engines are of variable quality. The mean DISCERN score of 43 represents information of moderate quality, with potentially important but not serious shortcomings. Consistent with previous studies, this study demonstrated that hospital institution created sites did not always provide better information in terms of content, however the quality was consistently good [8]. It was also noted one commercial site achieved the highest mean DISCERN score, an inconsistency with some previous comparable studies, but may result from the small number of commercial sites encountered in this study. Overall, these data suggest that patients searching the Internet can reliably be directed to sites provided by hospital associated sites and non -profit sites for relevant content as defined by the adrenalectomy specific score.

In 2013, the WHO approved a resolution on E-health standardisation and acknowledged the importance of standardized, accurate, timely data and health information to the functioning of health systems and services [23]. In contrast to some previously published studies, the resultant websites in this study contained predominantly correct and trust worthy information, and the websites analysed did not contain false or misleading information [2]. No websites contained information on natural remedies or treatment options other than current standard of care. Their main short comings and reason for lower DISCERN and JAMA scores were, in many cases, a lack of inclusion details of authorship and failure to disclose relevant references and sources. Another point worth highlighting was that may of the websites analysed had not been updated in several years. Due to the ever-changing nature and fast paced advances of evidence based medicine, sites that are not updated may not include the most recent health related options or evidence.

This study indicates that for Internet searches on adrenal surgery, the HONcode did not feature strongly. This is at odds with the findings of some similar studies investigating the quality of other health care topics, which found it to be associated with websites containing high quality information [15,21]. Thisis something that those responsible for compiling and maintaining health related websites should be aware of as a seal of quality. As physicians, it would be helpful to be able to direct our patients to look for this quality assurance marker when they search the internet.

Patients need to be made aware of the variability ofhealth information on the Internet and the need for discerning reading. Clinicians should take the time to educate ourselves on the information available to our patients and be able to identify high-quality sites and to direct them to appropriate sites. One previously published study found that patients rated information obtained on the internet as “the same as” or “better” than that from their doctor, and frequently did not discuss the information they sought elsewhere with their doctor [3]. The negative ramifications of this, if patients find suboptimal information online could potentially be wide reaching. The doctor-patient trust relationship may be compromised and patients may opt to proceed with treatment options that are suboptimal [24]. In addition, obtaining conflicting information from sources other than their clinician may lead to unnecessary stress and anxiety in patients. In contrast, where reliable online information is used as an adjunct, it may enhance the doctor-patient relationship and lead to more meaningful conversations around treatment planning [24]. It is necessary for physicians to be aware that their patients may be inadequately informed and to spend time addressing patients' perceptions. Finally, physicians could also become involved in posting content online themselves, although this admittedly takes time and certain skillsets.

Conclusion

This study highlights the need for the creation of reliable, contemporary, and concise on-line information for patients with regards to adrenal surgery.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that this study has some limitations. The DISCERN score, while a robust and well-established method of assessing medical websites, is subjective and therefore may lead to bias. This work represents an assessment of information quality at one point in time and does not represent or assess for temporal trends. This may also impact the accessibility of information contained on a website for patients with poor literacy skills, however the authors felt it was outside of the scope of the present study to analyse this. The authors acknowledge that search engine results may vary depending on location in the world. Although the study was conducted without logging into an account, the study was conducted in Europe only and it is difficult to determine whether different results would be obtained in other areas of the world. Finally, this study did not endeavour to determine the readability of any of the websites visited.

Nonetheless, this study highlights the need for the creation of reliable, contemporary, and concise on-line information for patients with regards to adrenal surgery.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study as it did not require the collection of human tissue, data or the involvement of human or animal participants.

Availability of Data

All data included in this study can be provided in the form of an excel file upon request to the corresponding author. No public repositories currently exist in which to upload this type of data, to the authors knowledge.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to and reviewed the final manuscript for submission.

References

- Hämeen-Anttila K, Pietilä K, Pylkkänen L, et al. (2018) Internet as a source of medicines information (MI) among frequent internet users. Res Social Adm Pharm 14: 758-764.

- Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, et al. (2015) Healthcare information on YouTube: A systematic review. Health Informatics J 21: 173-194.

- Diaz JA, Griffith RA, Ng JJ, et al. (2002) Patients' use of the Internet for medical information. J Gen Intern Med 17: 180-185.

- Silberg WM, Lundberg GD, Musacchio RA (1997) Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: Caveant Lector et viewor-Let the reader and viewer beware. JAMA 277: 1244-1225.

- Oxman AD, Paulsen EJ (2019) Who can you trust? A review of free online sources of "trustworthy" information about treatment effects for patients and the public. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 19: 35.

- Sadah SA, Shahbazi M (2016) Demographic-Based content analysis of web-based health-related social media. 18: e148.

- Grewal P, Alagaratnam S (2013) The quality and readability of colorectal cancer information on the internet. Int J Surg 11: 410-413.

- Van der Marel S, Duijvestein M, Hardwick JC, et al. (2009) Quality of web-based information on inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 15: 1891-1896.

- Priyanka P, Hadi YB, Reynolds GJ (2018) Analysis of the patient information quality and readability on Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) on the Internet 2018: 2849390.

- Teh J, Wei J, Chiang G, et al. (2019) Men's health on the web: An analysis of current resources. World J Urol 37: 1043-1047.

- Sacks S, Abenhaim HA (2013) How evidence-based is the information on the internet about nausea and vomiting of pregnancy? J Obstet Gynaecol Can 35: 697-703.

- Nassiri M, Bruce-Brand RA, O'Neill F, et al. (2015) Perthes Disease: The quality and reliability of information on the Internet. J Pediatr Orthop 35: 530-535.

- Nghiem AZ, Mahmoud Y, Som R (2016) Evaluating the quality of internet information for breast cancer. Breast 25: 34-37.

- Connelly TM, Khan MS, Victory L, et al. (2018) An assessment of the quality and content of information on diverticulitis on the internet. Surgeon 16: 359-364.

- Kaicker J, Borg Debono V, Dang W, et al. (2010) Assessment of the quality and variability of health information on chronic pain websites using the DISCERN instrument. BMC Med 8: 59.

- Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, et al. (1999) DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health 53: 105-111.

- Braun LA, Zomorodbakhsch B, Keinki C, et al. (2019) Information needs, communication and usage of social media by cancer patients and their relatives. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 145: 1865-1875.

- Beck F, Richard JB, Nguyen-Thanh V, et al. (2014) Use of the internet as a health information resource among French young adults: Results from a nationally representative survey. J Med Internet Res 16: e128.

- Łaski D, Perdyan A, Spychalski P, et al. (2020) Patients seeking information about colonoscopy - lessons learned from Google. Prz Gastroenterol 15: 144-150.

- (2020) Stats Global.

- Bruce-Brand RA, Baker JF, Byrne DP, et al. (2013) Assessment of the quality and content of information on anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on the internet. Arthroscopy 29: 1095-1100.

- Boyer C, Baujard V, Geissbuhler A (2011) Evolution of health web certification through the HONcode experience. Stud Health Technol Inform 169: 53-57.

- World Health Organisation

- Harvey S, Memon A, Khan R, et al. (2017) Parent's use of the Internet in the search for healthcare information and subsequent impact on the doctor-patient relationship. Ir J Med Sci 186: 821-826.

Corresponding Author

Helen Earley, Professorial Surgical Unit, Tallaght University Hospital, Tallaght, Dublin 24, Ireland

Copyright

© 2022 Earley H, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.