Push Endoscopic Button Gastrostomy in Childhood: Fewer Complications than Historical Surgical Techniques?

Abstract

Background/purpose: There is no consensus when it comes to the best procedure or device used for gastrostomy creation in pediatrics. We compared the complications encountered with different gastrostomy techniques.

Methods: All paediatric patients having had a gastrostomy procedure between 2004 and 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. Overall, serious and local complication rates at six months were compared between PEG-button (PEG-B), pull-PEG tube (PEG-T) and surgical gastrostomies with buttons (SG-B).

Results: Complications occurred in 44.6% of the patients. The rate of overall complications (71.4% vs. 50.0%, p = 0.02) as well as minor complications (93.3% vs. 69.0%, p < 0.01) was higher in the PEG-B group (63 patients) compared to the PEG-T group (58 patients) but similar to the SG-B group (83 patients). Serious complications mainly occurred in the PEG-T group (31.0% vs. 6.7%, p < 0.01). Risk factors for overall complications were being a female (Odds ratio (OR) 2.62, p < 0.01) and a concomitant fundoplication (OR 8.94, p = 0.04), whereas serious complications were favoured by the use of a G-tube (OR 3.78, p = 0.01).

Conclusions: A PEG-B is a simple and safe way for enteral nutrition, with a slightly higher rate of local, but less serious, complications than the classic pull-PEG technique.

Keywords

Gastrostomy, Endoscopy, T-Bar Gastropexy, Complications

Introduction

Gastrostomy is a recognized solution for long-term enteral feeding for paediatric patients with failure to thrive. Indications include multiple conditions: feeding disorders (eg: neurologically impaired children), dependency on fluid and nutritional supplementation, congenital or acquired pathologies in which oral intake is impeded (eg: oesophageal atresia, craniofacial surgery) and patients with long-term inadequate intake (eg: cancer, cystic fibrosis).

Various techniques have been described for gastrostomies: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), traditional Stem open procedure, PEG with fluoroscopy, laparoscopic technique, laparoscopic assisted PEG. Since the first description by Gauderer in 1980, PEG has considerably evolved and become the gold standard for long-term enteral access [1,2]. The Pull technique, characterized by the use of a feeding tube, having been the subject of many improvements has become simple, fast, reliable and well tolerated. However, the frequent use of a gastrostomy button, replacing the tube, has led to the development of the "Push" technique. This method, called the "one-step-button" has been described in adults in 1991 by Ferguson, et al. [3] and in children in 1993 by Treem, et al. [4]. This percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy procedure using a gastrostomy button became our standard procedure in 2010. In this procedure, the stomach is attached to the wall by T-bars which have a limited lifespan. Our experience has shown that this technique could be burdened by significant morbidity leading to emergency room consultations and anxiety for parents. Indeed, numerous complications, such as local infections, especially of the trans-parietal gastropexy T-bars, could be listed with this technique.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the rate of short term complications encountered after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) with "one-step-button" compared to historical PEG tubes and surgical buttons. We also compared the efficiency of enteral nutrition in all procedures.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A retrospective systematic review using medical records was conducted for all patients who underwent a gastrostomy procedure between 2004 and 2016 in one university hospital. As legally required at the time of beginning this study, the study has been declared to the Institutional Review Board, to the Commission National Informatique et Liberté (CNIL, number 2016-008), and met the requirements of the Helsinki declaration.

All children (under 16 years of age) who underwent either surgical gastrostomy or PEG were included. The exclusion criteria are patients 16 years or older and patients having had a surgical insertion of a gastric tube.

Three groups were defined by the technique used:

• Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy group with tube: PEG-T group

• Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy group using a gastrostomy button: PEG-B group

• Surgical gastrostomy group by laparotomy or laparoscopy using a gastrostomy button: SG-B group.

Data were compiled on patient's age at surgery, underlying pathologies and comorbidities, surgical indications (gastrostomy +/- anti-reflux system), type of medical device used (button or tube), immunodeficiency and the use of proton pomp inhibitors (PPI). Weight and height were registered at surgery and at 6 months. Postoperative complications were registered until 6 months after surgery. We considered that after this period the complications were not linked to the medical device used.

The main outcome variable was the overall postoperative complication rate at 6 months for each technique to highlight a potential higher risk of the PEG-B technique compared to other techniques. Therefore, we registered the time between the procedure and the occurrence of the first complication. An early complication was defined as occurring within 30 days of the procedure.

Secondary outcome variables were:

• Efficiency of gastrostomy enteral nutrition in the different groups, assessed through weight gain at 6 months and evaluation of undernutrition. Undernutrition was defined as Z-score Weight/Height inferior to -2 standard deviations [5].

• Comparison of the complication rates between the groups stratified by the Clavien-Dindo classification [6], according to the care required: Minor (Clavien grade I or II = medical treatment) or serious (Clavien grade III or IV = reoperations or requiring treatment in an intensive care unit).

• Assessment of risk factors for PEG-B procedure complications.

Surgical techniques

All endoscopic procedures were performed under general anesthesia and with preoperative antibio-prophylaxis (2nd generation cephalosporin) using a flexible gastroscope. The procedure was performed by a pediatric surgeon, assisted by a gastroenterologist.

Our preferred choice of procedure was the endoscopic creation of a gastropexy with SAFE-T-PEXY® fixation (PEG-B), using a Kimberly-Clark MIC-KEY* G Introducer kit (Halyard, distr. AseptInMed, France), following the manufacturer's instructions. To secure the procedure, the gastric button (MiniONE® balloon button, Applied Medical France, Paris, France) was inserted through the peel-away sheath and over the J-guidewire left in place. During the following weeks, the gastropexy T-bars then progressively dissolved, dropping off into the stomach, and were evacuated spontaneously. We didn't cut the T-bars, unless there were signs of local inflammation or pain, to make sure the gastric wall had enough time adhere to the anterior abdominal wall.

Previously, gastrostomy tubes were inserted using the pull approach, as described by others [1]. Tubes were either left in position, or replaced after 3-6 months by a button, the tube being cut down to skin level, and the bumper evacuated in the patient's stools.

Surgical procedures were performed through a 4-cm median sus-umbilical laparotomy incision or under laparoscopy. The majority (90%) were performed at the end of a fundoplicature procedure. We chose to group them together because the key-steps of gastrostomy creation, e.g. fixation of the stomach to the abdominal wall and insertion of the button, were the same. The lower part of the anterior face of the stomach was attracted to the inner face of the abdominal wall, and opened in the centre of a circular absorbable suture. A gastric button was inserted through a 5 mm skin incision or at the place of the epigastric trocar into the stomach and the balloon inflated with tap water. The circular suture was closed around the button, and the stomach fixed to the parietal peritoneum by three absorbable stitches.

Postoperative pain was managed with level 1 or 2 analgesics, as required by repeated pain evaluation. No local injection of analgesics was performed to prevent the risk of infection. Enteral nutrition was started the day after surgery, first with a bolus of water (2 ml.Kg-1.h-1), followed, if well tolerated, by an enteral nutrition product adapted to the patients needs. No specific protocol was used for local inflammation treatment; usually, local antiseptics such as an aqueous chlorhexidine solution were applied twice a day until regression of symptoms. If necessary, a probabilist antibiotherapy (oral or intraveinous) could be added to local treatments. Symptomatic granuloma was treated by repeated application of silver nitrate at a frequency of once a week to every two days, and/or by daily application of betamethas one dipropionate.

Data analysis

Patients' characteristics were presented as effectives (frequencies) for qualitative variables, and means ± standard deviation, or median - [Inter-Quartile Range (IQR)], as appropriate, for continuous variables. A comparison of these characteristics between groups was performed using a Chi [2] or a Fisher exact test for qualitative variables depending on the amount of patients and a Student or Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test for quantitative variables according to the normal distribution assumption.

Risk factors associated with complications were determined using logistic regression. Univariate analysis was firstly performed to determine variables associated with the complications. They were selected for the final model if the P value for association was below 20%, or if known to be a potential confounding factor. The search for interactions was performed from the final model. Only interactions clinically relevant and interpretable were examined. The final model was determined after a manual backward selection.

All analyses were performed using R software. All tests were 2-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Population description

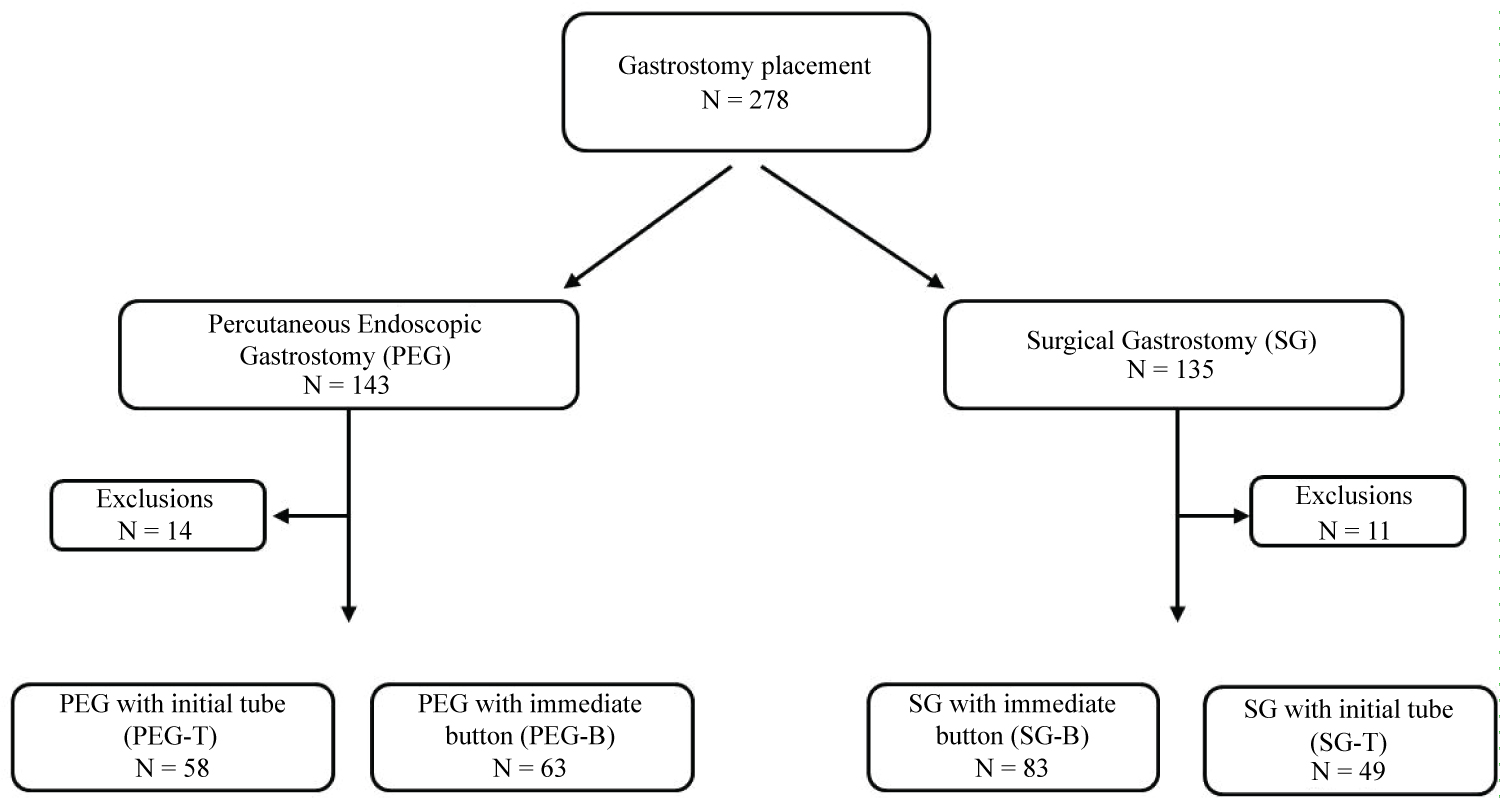

Two hundred and seventy-eight gastrostomy procedures were performed as encoded in the hospital chart under CIM10 numbers (HFCA002, HFCB001 and HFCC002), 135 with a laparoscopic/laparotomic procedure and 143 with an endoscopic approach. Twenty five patients were excluded from analysis due to an age at gastrostomy procedure ≥ 16 years (n = 15), a lack of data (n = 7), encoding errors (n = 2) or transfer to another hospital (n = 1). Forty nine patients had surgical gastric tube procedures (SG-T group); for information, their baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1 with the three other groups, but no further comparison was made with this group. The flowchart in Figure 1 shows the distribution of the patients across the different subgroups of analysis.

Median age at gastrostomy insertion was 2.5 [0.0-15.7] years. Baseline characteristics of the patients including ontological data, underlying disease or associated pathological conditions, and associated medical or surgical treatments are summarized in (Table 1). To sum up, patients in the SG-B group were younger and smaller than in PEG groups due to the more frequent occurrence of congenital malformative conditions, resulting in a higher rate (90%) of concomitant fundoplication. All these patients completed the six month follow-up.

Efficiency of gastrostomy feeding

At baseline, under nutrition was present in 56% of the patients: 54% of the patients in the PEG-B group, 63% in the PEG-T group and 50% in the SG-B group (non-significant, ns). Mean Z-score W/H was -1.02 +/- 2.17, without significant difference between groups.

Nutritional status improved after six months of gastrostomy feeding in all subgroups to achieve a mean Z-score W/H of -0.5 +/- 1.8 and under nutrition persisted in only 31.6% of the patients.

Complications after gastrostomy procedures

As we hypothesized that a difference in the rate of complications could be due to either the insertion technique (endoscopy or surgery), the device being the same button, or to the device itself (G-tube or button with T-bar fasteners) installed through endoscopy, we have independently analysed the complications amongst the three subgroups in our population.

In the PEG-B group, 45 complications (71.4%) occurred in 31 patients within six months after PEG insertion. Forty-two (93%) of them were considered as minor complications, and the three others were classed Clavien 3b: One perforation of the posterior gastric wall happened during PEG insertion, requiring immediate conversion to laparotomy; one infection with abdominal wall necrosis around the button occurred in a patient with bone marrow aplasia, which required surgical debridement and controlled wound healing; and one gastrostomy falling out which required another operation. Minor complications were made up of buttons falling out simply needing immediate reinsertion (n = 3), granuloma (29%, n = 13) treated by local corticosteroids or silver nitrate application, and peristomial inflammations (44%, n = 20) treated with general antibiotics in 12 cases (60%) or local treatment in 4 cases (15%). Overall, 10 complications were directly related to the anchors: 4 local infections, 3 granulomas, 1 persistant pain, 1 inclusion of the T-bar in the abdominal wall, 1 leak of gastric fluids; all were treated by T-bar resection, coupled with local treatment for granulomas and antibiotics for infections.

In the PEG-T group, there were less complications with 29 (50%, p = 0.02) in 19 (33%) patients. Twenty (69%, p = 0.008) of them were considered minor, and Clavien 3 complications occurred in 9 cases, including 5 tube dislodgements, 3 gastric occlusions after section of the inner collar and 1 gastrostomy repair due to pain. Local complication rates and their treatment methods did not differ from the PEG-B group, with 6 (21%) granulomas and 9 (31%) local inflammations.

In the SG-B group, the rate of overall complications was similar to the PEG-B group, with 61 complications (73.4%) occurring in 41 (49.3%) patients (ns). Minor complications occurred in 57 (93%) of the cases, the rate of local inflammation and granuloma being respectively 34% and 44%, similar to the PEG-B group. Gastrostomy inflammation was however more often treated by the use of locally applied antiseptics (57% of the cases, p = 0.02) and the use of general antibiotics was reduced to 5% (p < 0.001), compared to the PEG groups. Four complications (6.6%) were classified Clavien 3b, three of them being button dislodgements requiring reinsertion under general anaesthesia and one being an evisceration of the laparotomy scar, requiring wall suture.

Comparing the PEG-B group to the other ones (Table 2), mean time between surgery and the occurrence of complications was significantly shorter (63.5 ± 39.4 days) than in the PEG-T group (95.1 ± 49.0 days), but comparable to the SG-B group, the number of patients experiencing an early complication (23%) being however half as many as after surgical gastrostomy (51%).

The rate of overall (71 and 73%) and minor (93%) complications were the same in both groups with direct button use, whereas, compared to the PEG-T group, percutaneous insertion of the button was linked to a higher risk of complications (71 vs. 50%, odds ratio OR = 2. 5, 95% CI [1.1-5.7], p = 0.02), mainly due to minor complications (93.3% vs. 69.0%, OR = 6.1, 95%CI [1.3-39.1], p = 0.008). In our series, no patient experienced a Clavien 4 complication, and postoperative Clavien 3b complications mainly occurred in patients with gastrostomy tubes, and could be directly linked to the use of this type of device. Hence, five burried bumper or device dislodgements and 3 intestinal occlusions due to the impaction of the collar in the intestinal system after section for tube replacement required surgery.

When it comes to local complications, inflammation and granuloma were the two most common (42.7% and 39.0% respectively), three times more frequent than device dislodgement (13.7%), and 10 times more frequent than gastric fluid leakage (4.3%), without significant difference in rates between groups.

Risk factors for gastrostomy complications

We performed further analysis on our whole gastrostomy population (253 patients, including surgical G-tubes), to look for specific complication risk factors. Potential criteria were age (≤ 1 month), sex, underlying pathology (neurological impairment, oncology, malformative conditions, and metabolism abnormality), surgical technique (PEG, laparotomy or laparoscopy), device (gastrostomy tube or button), concomitant fundoplication, proton pump inhibitor use, under nutrition and immunosuppression.

Univariate analysis did not show any specific risk for overall complications, nor did detailed analysis of serious complications and local complications (granuloma inflammation and leak of gastric content).

After multivariable logistic regression (Table 3), the occurrence of complications after gastrostomy insertion was favored by being a female (OR = 2.6, p = 0.02), and a concomitant fundoplication (OR = 8.9, p = 0.049). To clarify, the occurrence of specific complications only associated with fundoplication, such as transient dysphagia, have been excluded from the analysis.

Serious complications (Table 3) were three times more likely to occur in girls (p = 0.03), and four times more likely to occur if a G-tube was used as the first gastrostomy device (p = 0.01). When it comes to local complications (Table 4), no specific risk factor was identified for local peristomial inflammation, whereas granuloma was three times less likely to appear when a G-tube was used (OR = 0.35, p = 0.008), and leak of gastric content was only related to female sex (OR = 8.4, p = 0.002). Young age did not appear to be at risk for gastrostomy complications, and neither the gastrostomy technique nor the initial device used was related to peristomial inflammation or leak of gastric content.

Discussion

The originality of this retrospective study, aimed at comparing gastrostomy complications in children, was that it looked at both the technique, surgical or endoscopic, and the type of device used, button or tube. If the efficiency of gastrostomy feeding was the same in all groups after 6 months, it appeared that the use of a G-tube was at risk of serious surgical complications compared to a button, regardless of the technique used. Hence, up to 31% of complications were classed Clavien 3 when a G-tube was used, and most of them were directly related to this device. Buried bumpers, caused by the sub ischemia of the walls enclosed between the inner collar and the external ring if too tightened, and tube dislodgements have been known about for a long time [7,8], and may be reduced by the use of a low-profile button [9]. Gastric or intestinal occlusion caused by the inner collar after section of the tube for replacement of the device without endoscopic tube removal was responsible for 10% of the complications after G-tube insertion in our series as opposed to 2-3% in other studies [10-13]. This technique of G-tube removal had been chosen in our facility to avoid another general anaesthesia and endoscopy for tube replacement, and because there was a risk of gastric wall disinsertion in case of trans-abdominal extraction of the tube.

In this series, we reported a rate of 11.9% serious complications, which seems to be comparable to previous published works. Hence, Khattak, et al. [13] ound a rate of 17.5% serious complications at 12 months after pull-PEG insertion, Kvello, et al. [14] reported a 17.5% rate of early postoperative (< 30 days) serious complications after laparoscopic gastrostomy, and Balogh, et al. [15], reported a 10% major complication rate in a recent systematic revue of PEG complications in children. As opposed to the type of device used, we didn't find a link between the technique used (PEG or surgical) and the occurrence of serious complications. A recent meta-analysis by Baker, et al. [16], found no difference in the occurrence of major complications between laparoscopic versus open tube, and open tube versus PEG. However, PEG had a significantly increased risk of major complications when compared to laparoscopic G-tube (OR 0.29, p = 0.0001), essentially due to visceral injuries or bleeding. We weren't able to confirm that being young, having a lower weight and neurological impairment were protective factors against major complications as did Mc Sweeney [17].

Almost half of our patients experienced minor complications, about 90% of them being local ones. This is relatively high when compared to the literature, where local complications rates range from 20 to 33% [16,18-21] after PEG or laparoscopic gastrostomy, but the majority of these studies looked into 30 to 90 day postoperative complications, whereas we reported results from a longer 6-month postoperative follow up; our early complication rate was 21.1%, and mainly with surgical gastrostomies (Table 2). The rate of local complications didn't appear to be made worse by the use of a PEG-button, compared to PEG-T and SG-B gastrostomies. The type of complication (local inflammation, granuloma, leak of gastric fluid) and the timeframe of occurrence were the same in both groups using a button, and the use of percutaneous T-bars in the PEG-B group didn't increase the risk of skin infection. On the whole, no particular risk factor was identified for the occurrence of minor and local complications, neither patient's characteristics such as age or underlying pathology, nor technical data (insertion technique, device used, etc...). Some recent studies about gastrostomies have shown that patients under 10 Kg [21] or neurologically impaired [15] weren't at higher risk of complications.

Local skin inflammation or infection were not more frequent in patients with an underlying immunosuppressive condition, nor prevented by the use of proton pump inhibitors. As the risk of skin infection may greatly decrease with the use of a preoperative anti bio prophylaxis [22], all of our patients received just before the gastrostomy procedure an injection of a 2nd generation cephalosporin, as recommended by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy [23]. In our series, inflammation was more often treated by applying local antiseptics in the SG-B group compared to PEG groups where systemic antibiotics were administered in 60% of the cases. This difference seems to be due to the fact that all cancer patients had a PEG, and that we preferred treating these patients, who have a high risk of severe infection due to their immunosuppression, with general antibiotics. In particular, the use of gastropexy T-bars was responsible for 4 local infections, but this didn't significantly increase the rate of local infections in the PEG-B group. There is little data in the literature regarding the gastropexy device. In a study by Terry, et al. [24], gastropexy wires were cut 10-14 days after PEG to prevent the migration of T-bars under the skin and causing gastric wall erosion. One recent study by Kvello, et al. [25] reported 23 (26%) complications due to T-bars in 87 paediatric patients, with either early complications such as local infection or pain or late complications that were mainly migrated T-fasteners. Another series [19] focusing on laparoscopic gastrostomies compared subcutaneous sutures to temporary trans-abdominal wall sutures and found similar rates for local minor complications, as did the study by Sutherland, et al. [20]. About PEG pull-type and push with T-bar technique.

Local granuloma was found to be favoured by a button device when compared to a G-tube (OR = 2.8, p < 0.01). There is little specific data about granuloma, but other series [26] have found rather high rates (~50%) of granuloma after direct button use when compared to G-tubes (10-19%) [15,27]. The study by Sutherland, et al. [20], found a higher rate of granuloma after G-tubes when fascial suture was performed and Liu, et al. [28]. When a concomitant fundoplicature was performed, One explanation could be that the low-profile button may give an hourglass shape to the gastrostomy hole, which favour mucosal prolapse.

Taking overall complications into account, multi variate analysis showed girls had a riskthat was 3 times higher than boys to experience a complication and that a concomitant fun duplication significantly increased the risk of complications. The latter has recently been assessed through a meta-analysis by Yap, et al. [29], in which a concomittant fundoplication increased the risk of overall and minor complications, without reducing significantly reflux-related symptoms. To our knowledge, being a female has not yet been considered a risk factor for gastrostomy complications, and we didn't find any medical explanation for this result. It would seem that this was the case more specifically for serious complications and gastric fluid leaks.

Being a retrospective study, our work is subject to all the limitations associated with this type of analysis, including missing data and changes of surgical practices over time (use of tubes and then buttons). Another potential selection bias is the difference in baseline characteristics, such as weight and underlying conditions, between the groups of patients experiencing PEG or surgical gastrostomy. This difference is mostly due to the fact that infants often suffer from malformative conditions or neurological impairment, and thus require a concomitant fund application [19]. On the contrary, cancer patients always had a PEG to decrease the risk of postoperative infection. Nevertheless, many studies have consistently shown that complication outcomes didn't differ between young and older children [16,22,30]. This is why we found it legitimate to keep these groups for complication comparisons, while taking this into account for multivariate analysis by connecting fundoplication with age, underlying conditions and the choice of the surgical technique.

Conclusions

There is currently no consensus regarding the optimal technique for gastrostomy procedures, nor for the type of device to be used in the paediatric population, and there remains a lack of well-designed trials to answer this question. However, the direct insertion of a low-profile button may be considered as a better procedure than tube placement for children in order to lower the risk of major complications.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ, et al. (1980) Gastrostomy without laparotomy: A percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg 15: 872-875.

- Michaud L, Guimber D, Blain-Stregloff AS, et al. (2004) Longevity of balloon-stabilized skin-level gastrostomy device. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 38: 426-429.

- Ferguson DR, Harig JM, Kozarek RA, et al. (1993) Placement of a feeding button ("one-step button") as the initial procedure. Am J Gastroenterol 88: 501-504.

- Treem WR, Etienne NL, Hyams JS, et al. (1993) Percutaneous endoscopic placement of the button gastrostomy tube as the initial procedure in infants and children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 17: 382-386.

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA, et al. (2004) Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240: 205-213.

- Stewart CE, Mutalib M, Pradhan A, et al. (2017) Short article: Buried bumper syndrome in children: Incidence and risk factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 29: 181-184.

- Cyrany J, Rejchrt S, Kopacova M, et al. (2016) Buried bumper syndrome: A complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. World J Gastroenterol 22: 618-627.

- Novotny NM, Vegeler RC, Breckler FD, et al. (2009) Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy buttons in children: Superior to tubes. J Pediatr Surg 44: 1193-1196.

- Waxman I, al-Kawas FH, Bass B, et al. (1991) PEG ileus. A new cause of small bowel obstruction. Dig Dis Sci 36: 251-254.

- Mutabagani KH, Townsend MC, Arnold MW, et al. (1994) PEG ileus: A preventable complication. Surg Endosc 8: 694-697.

- Agaba Ae, Sarmah Ss, Victor Babu Ba, et al. (2007) Small bowel obstruction caused by intraluminal migration of retained percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy internal bumper. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 89: 1-5.

- Pearce CB, Goggin PM, Collett J, et al. (2000) The cut and push method of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube removal. Clin Nutr 19: 133-135.

- Khattak IU, Kimber C, Kiely EM, et al. (1998) percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in paediatric practice: Complications and outcome. J Pediatr Surg 33: 67-72.

- Kvello M, Knatten CK, Bjornland K, et al. (2020) Laparoscopic gastrostomy placement in children has few major, but many minor early complications. Eur J Pediatr Surg 30: 548-553.

- Balogh B, Kovacs T, Saxena AK, et al. (2019) Complications in children with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement. World J Pediatr 15: 12-16.

- Baker L, Beres AL, Baird R, et al. (2015) A systematic review and meta-analysis of gastrostomy insertion techniques in children. J Pediatr Surg 50: 718-725.

- McSweeney ME, Kerr J, Jiang H, et al. (2015) Risk factors for complications in infants and children with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes. J Pediatr 166: 1514-1519.

- Fortunato JE, Troy AL, Cuffari C, et al. (2010) Outcome after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children and young adults. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 50: 390-393.

- Mason CA, Skarda DE, Bucher BT, et al. (2018) Outcomes After Laparoscopic Gastrostomy Suture Techniques in Children. J Surg Res 232: 26-32.

- Sutherland C, Carr B, Biddle KZ, et al. (2017) Pediatric gastrostomy tubes and techniques: Making safer and cleaner choices. J Surg Res 220: 88-93.

- Bawazir OA (2020) percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children less than 10 kilograms: A comparative study. Saudi J Gastroenterol 26: 105-110.

- Sharma VK, Howden CW (2000) Meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of antibiotic prophylaxis before percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol 95: 3133-3136.

- Rey JR, Axon A, Budzynska A, et al. (1998) Guidelines of the european society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (E.S.G.E.) antibiotic prophylaxis for gastrointestinal endoscopy. European Society Of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Endoscopy 30: 318-324.

- Terry NE, Boswell WC, Carney DE, et al. (2008) percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with t-bar fixation in children and infants. Surg Endosc 22: 167-170.

- Kvello M, Knatten CK, Perminow G, et al. (2018) Initial experience with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with t-fastener fixation in pediatric patients. Endosc Int Open 6: 179-185.

- Angsten G, Danielson J, Kassa AM, et al. (2015) Outcome of laparoscopic versus open gastrostomy in children. Pediatr Surg Int 31: 1067-1072.

- Viktorsdottir MB, Oskarsson K, Gunnarsdottir A, et al. (2015) Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in children: A population-based study from iceland, 1999-2010. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 25: 248-251.

- Liu R, Jiwane A, Varjavandi A, et al. (2013) Comparison of percutaneous endoscopic, laparoscopic and open gastrostomy insertion in children. Pediatr Surg Int 29: 613-621.

- Yap BK, Nah SA, Chen Y, et al. (2017) Fundoplication with gastrostomy vs gastrostomy alone: A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes and complications. Pediatr Surg Int 33: 217-228.

- Evans JS, Thorne M, Taufiq S, et al. (2006) Should single-stage PEG buttons become the procedure of choice for PEG placement in children? Gastrointest Endosc 64: 320-324.

Corresponding Author

Françoise Schmitt, MD, PhD, Pediatric Surgery Department, University Hospital of Angers, Rue Larrey, 49933 ANGERS cedex 9, France, Tel: +33-2-41-35-42-90, Fax: +33-2-41-35-36-76

Copyright

© 2021 Mariani A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.