Short Term Outcome in Operative Management of Posterior Wall and or Posterior Column Fractures of Acetabulum

Abstract

Background: Displaced posterior wall fractures and or posterior column fractures are not infrequent injuries of acetabulum and stable fixation are the goals of operative management when indicated, outcome of surgical treatment depends on many patient and fracture factors.

Objective: To assess Short Term Outcome in Operative Management of Posterior Wall and or Posterior Column Fractures of Acetabulum.

Methods: Prospective study on thirty patients was conducted for displaced posterior wall or posterior column fractures of acetabulum at Skims Medical College Bemina, Srinagar Kashmir from 01-08-2014 to 01-08-2015. All patients were evaluated clinically with Modified Merle d'Aubigne Score and Harris Hip score, and radiologically with Matta's radiological outcome grading. The effect of different parameters like sex, timing of reduction, timing of surgery and quality of reduction on the outcome was evaluated.

Results: The functional results were calculated using clinical grading system developed by Merle d, Aubigne and postel (1954) adopted by letournel and Judet (1993) and modified by Matta (1996). 6 patients were labelled as Excellent, 16 pts had good outcome and 6 pts had fair result while as 2 pts had poor result.

Conclusion: Satisfactory outcome can be obtained with open reduction and internal fixation of acetabular fractures in short term follow up. Although fracture complications are often complex, satisfactory results were achievable in majority of cases. The operative management of these fractures is being preferred as complications, especially long terms associated with conservative management are significant and associated with considerable morbidity.

Introduction

Majority of acetabular fractures occur primarily in young adults in the setting of significant high velocity trauma secondary to either a motor vehicle accident or high-velocity fall. Force exerted on the femur, passes through the femoral head, and is transferred to the acetabulum. The direction and magnitude of the force as well as the position of the femoral head determine the pattern of acetabular injury. The anatomical and radiographic classifications play an important role and acts as a first step in decision making for the mode of treatment [1]. Acetabular Fractures have always been challenging for orthopedic surgeons. They are more often seen in young active patients and have been associated with a high rate of post injury complications [2,3]. Kebaish, et al. in a long term follow up study, indicated that the results of non-operative treatment in displaced acetabular fractures were inferior compared to those of operative treatment (30% satisfactory results versus 80% satisfactory results in the surgical group) [4]. Surgical treatment by open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is indicated for most displaced acetabular fractures, this can restore the articular anatomy with rigid internal fixation, and allows early mobilization of the affected hip joint [5].

Several studies demonstrated that accurate reduction and rigid internal fixation can decrease the incidence of post-traumatic arthritis and improve functional outcome [6,7]. Operative treatment is hazardous because of deep location of the hip, the related neuro vascular structure, the complex anatomical features of the acetabulum, and other problems like the age of the patient, state of the bone, comminution etc can compromise the end result even in the hands of experienced surgeons [8,9]. Improved clinical outcomes are associated with younger age, few concomitant injuries, shorter time interval to surgery and more closely approximated anatomical fracture reduction [10].

Fracture of the posterior wall is the most common acetabular fracture. They accounted for nearly 47% of the total acetabular fractures according to a study of Letournel and Judet [8]. Operative treatment of fractures with an unstable hip or when a large part of the posterior wall is involved has been widely recommended for anatomical reduction and rigid fixation [8,9]. The long term results of operative treatment are influenced by numerous factors, including fracture type and or dislocation, femoral-head status, intra-articular osteochondral fragments, duration of injury, quality of reduction, local complications, associated injuries and surgical approach [3]. Osteoarthrosis of the hip joint, avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head and heterotopic ossification tend to result in poorer outcome despite good fracture reduction [10]. Fractures of the posterior column represent 3%-5% of acetabular fractures [11]. The posterior column fractures frequently fracture the greater sciatic notch at or above the location of the superior gluteal neurovascular bundle. In widely displaced fractures it is common to find the neurovascular bundle in the posterior column fracture site and it must be carefully extracted before reduction of the fracture to prevent iatrogenic injury [6,12]. This study has focused on operative management of posterior wall and/or posterior column fractures of the acetabulum, to assess the short term results.

Aims and Objectives

To assess the short term outcome in operative management of displaced posterior wall and /or posterior column fractures of acetabulum.

Material methods

This study was conducted on 30 cases of displaced posterior wall and /or posterior column fractures of acetabulum admitted in the department of orthopedics Skims Medical college, Srinagar, Kashmir from 01-08-2014 to 01-08-2015. The following criteria was used for selection of patients.

Inclusion criteria

1. Patients between 18 to 60 years of age.

2. Both sexes

3. Less than three weeks from the date of injury.

4. Posterior wall and/or posterior column fractures of acetabulum.

Exclusion criteria

1. Patients with open fractures

2. Patients having acetabular fractures other than posterior wall and /or posterior column.

3. More than three weeks since injury

4. Patients who had previous Osteoarthritis.

5. Pathalogical fracture

6. Bilateral acetabular fractures.

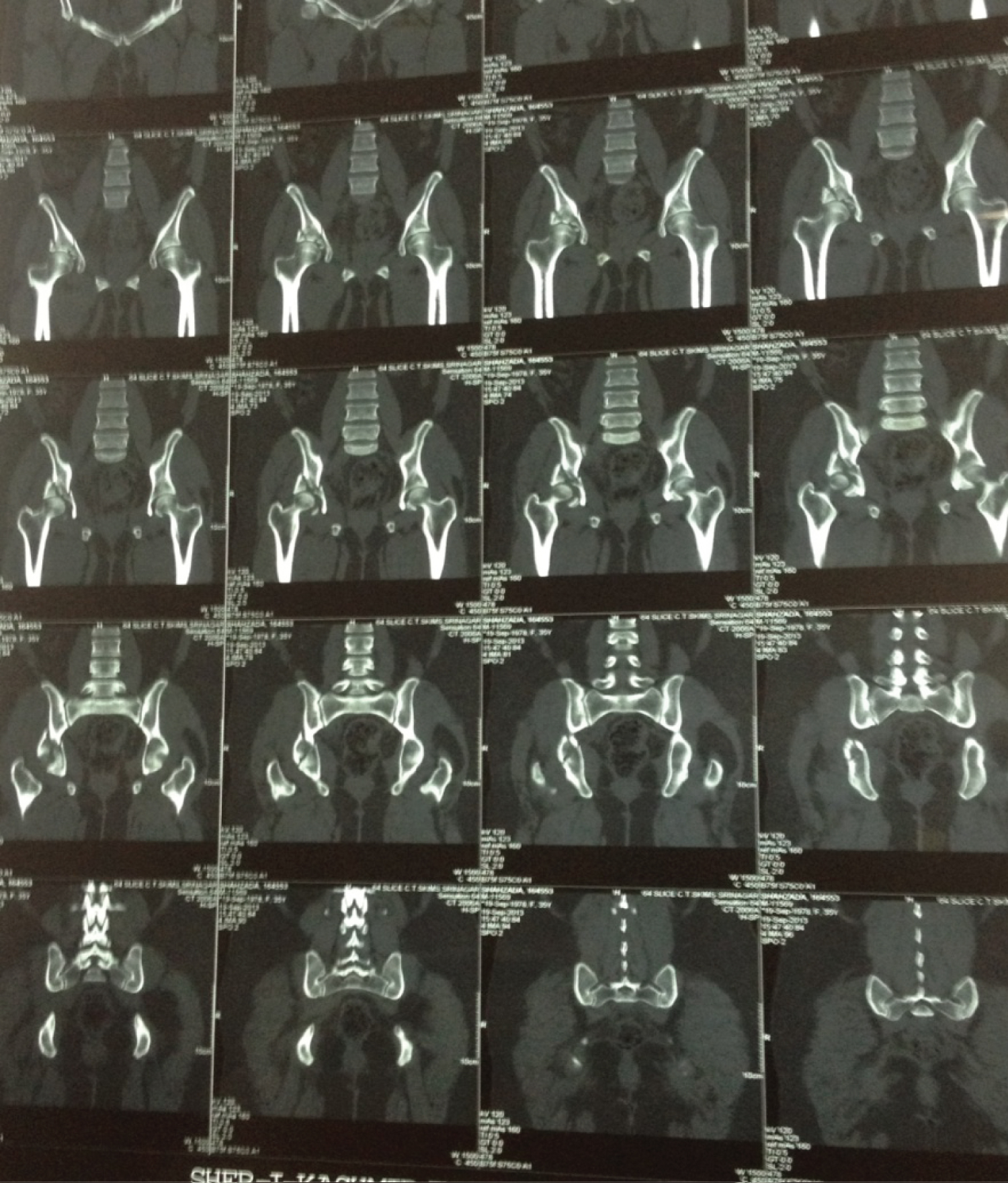

The patients were evaluated and stabilized by applying Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) sequence. A detailed history was taken and a thorough clinical examination was performed including general physical examination and local examination. Base line investigations were ordered. An AP X ray of pelvis with both hips, two oblique views (obturator oblique and iliac oblique) and 3D CT were taken pre-operatively in all the patients. On antero-posterior radiographs following 6 major lines and landmarks were observed i.e 1, posterior wall 2, anterior wall 3, dome 4, tear drop 5, ilioischial line 6, iliopectineal line. Any dislocation diagnosed and confirmed at this point was reduced. After this if an acetabular fracture was diagnosed oblique views were taken. On 45 degrees Oblique views (Judet views) following structures were visualized i.e Iliac Oblique view (judet) will depict anterior wall and posterior column and obturator oblique view (judet) will show Posterior wall and Anterior Column. The Letournel and Judet classification was used to classify displaced acetabular fractures. Indications for operation were:

1. Fracture displacement of >3 mm.

2. Unstable Hip after reduction.

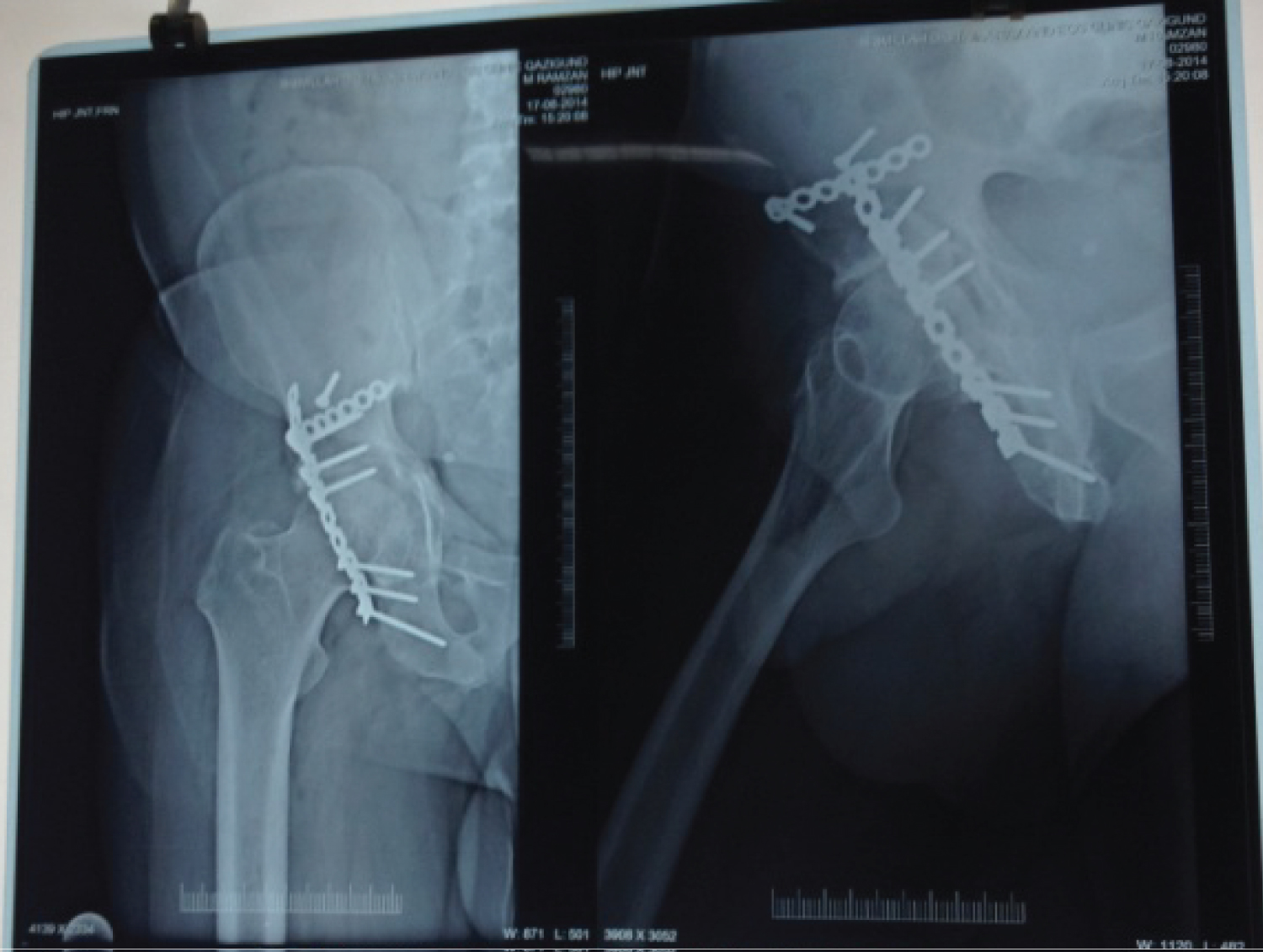

Patients were prepared and taken up for surgery within first two weeks after the injury after taking an informed consent. All the patients were given prophylactic antibiotic Inj Cefazolin 1 gm half an hour before surgery and continued for two days postoperatively. The surgery was done in the lateral or semi prone position. Surgery was done through Kocher- Langenbeck approach. Pre and post operative X ray (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9). Prophylaxis against heterotopic calcification was used by giving Indomethacin 25 mg thrice a day for 6 weeks [13]. Ambulation of the patients was started at 7-10 days post-operatively when permitted and was allowed partial toe touch weight bearing with use of crutches and progression to full weight bearing was individualized. The postoperative physiotherapy was directed primarily towards regaining muscle strength around the Hip especially abductors.

Skin Stitches were removed on 14th post operative day. Before discharge three standard radiographs were taken to assess the fracture reduction. Follow up was done at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months and at one year. (Figure 2) showing follow up X ray. Data including all complications were recorded at each visit. After 1 year follow-up the final outcome was evaluated using clinical grading system developed by Merle d, Aubigne and postel (1954) adopted by Letournel and Judet [8] and modified by Matta [3]. In this clinical grading system pain, ambulation and ROM of the hip was assigned a maximum of 6 points. The three individual scores were summed to derive the final clinical score according to which the clinical results were classified as excellent (18 points), good (15, 16, or 17 points), fair (13 or 14) and poor (< 13 points). Radiological outcome was also evaluated at one year follow-up, using Matta's Radiologic outcome criteria [3].

Observations and Results

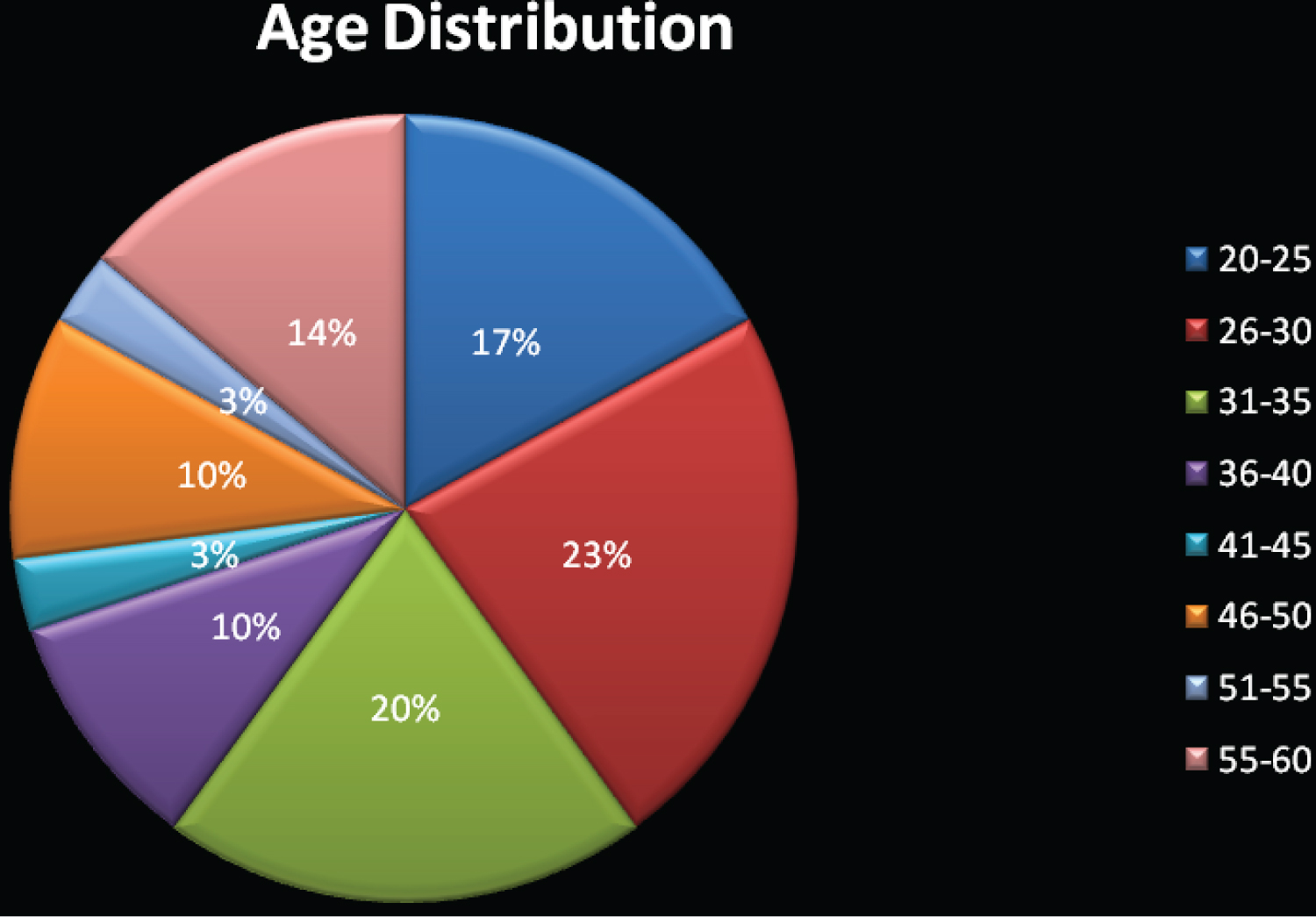

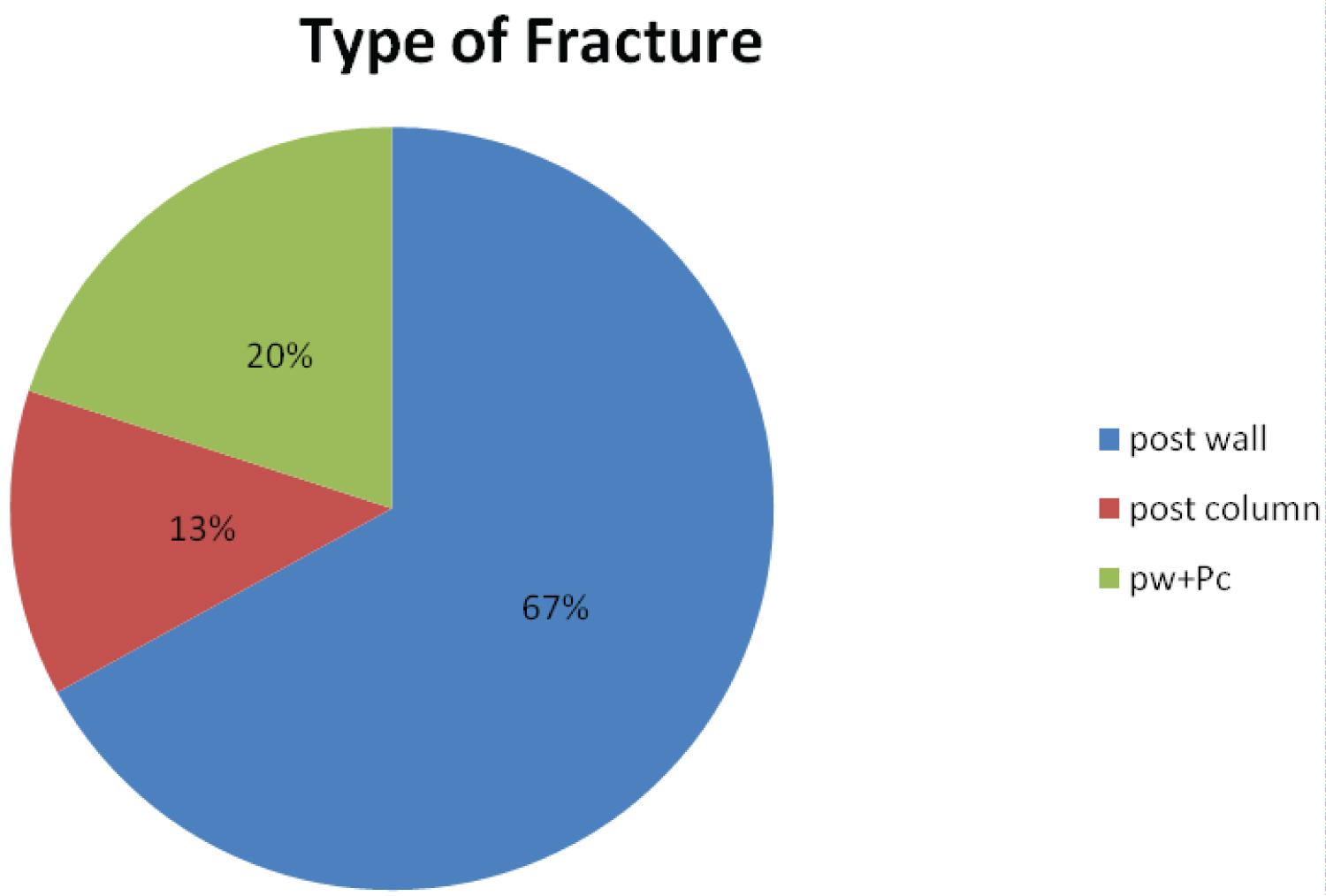

The mean age of patients in this study was 37.03 years ± 11.98 years. 70% of patients were aged 40 years or less and this difference was statistically significant (p value = 0.028, chi Square test). Majority of the patients were males (73%). (Statistically significant, p = 0.01). Right side was predominantly involved (56.77%). It was found statistically insignificant (p = 0.426, chi sq.test). In majority of the patients fracture occurred as a result of road traffic accidents (60%), in the rest fall from height was the mode of injury (40%) (Statistically not significant, p = 0.273). 11 of our patients had other associated injuries at the time of presentation. In our study most of the patients (66.66%) had fracture of the posterior wall of the acetabulum. This difference was statistically insignificant (p = 0.068. chi Sq test).

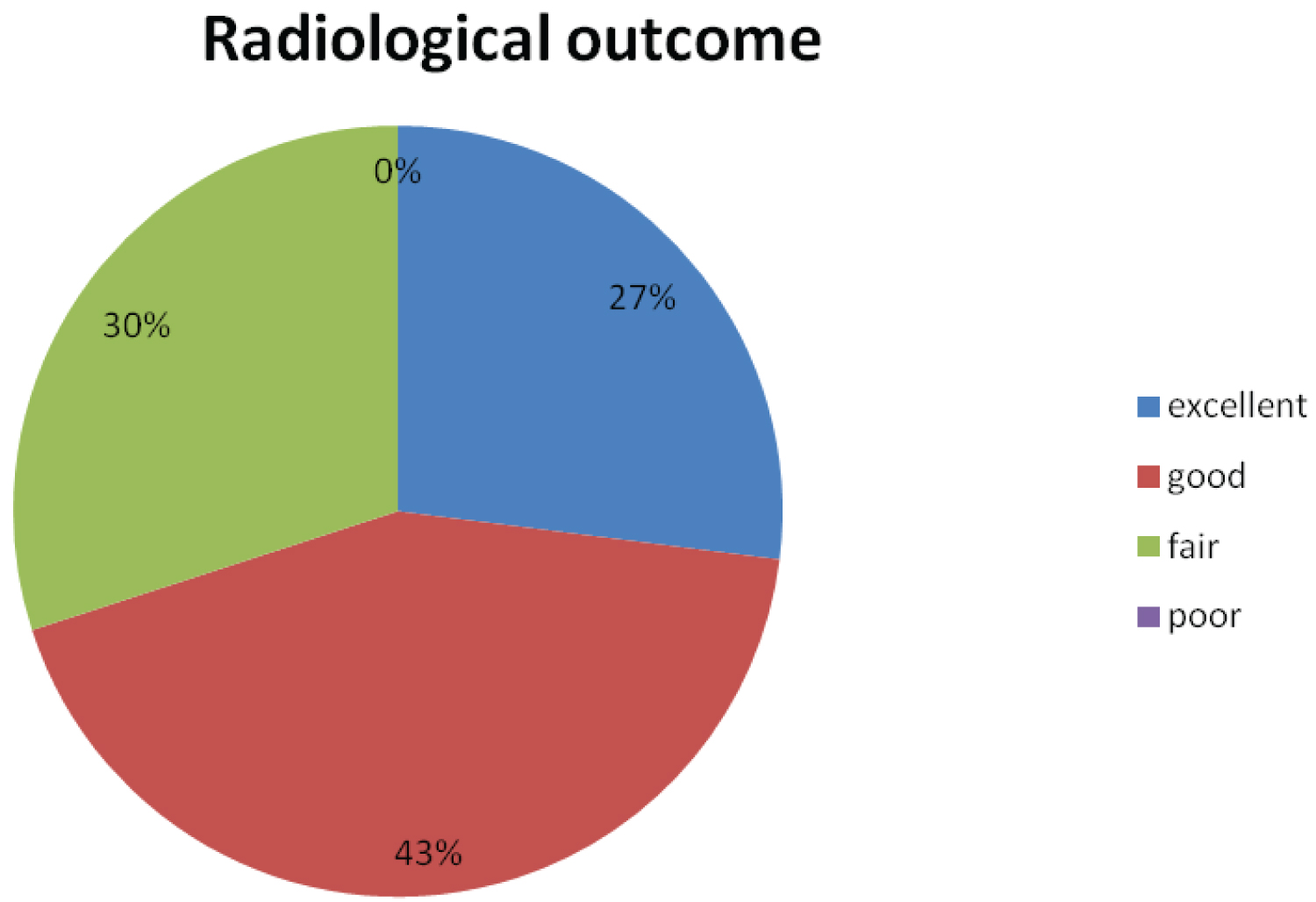

The mean interval between injury and surgery was 7.5 days ± 2.09 days. Majority of our patients were operated within 10 days of injury (93%). (Statistically significant, p = 0.000). The average surgical time was 151-7 ± 42.62 minutes (2 hours 31 minutes) (range 1 hour 40 minutes to 4 hours). In majority of the patients i.e 70%, operation was completed in 3 hours or less and this difference was found statistically significant (p = 0.028). Then average blood loss was 182.5 ± 45.7 ml. Hospital stay averaged 14.43 ± 3.48 days, with maximum of 22 days and minimum of 10 days. The average time to full weight bearing was 13.86 ± 2.04 weeks with a minimum of 12 weeks and maximum of 18 weeks. The duration of follow-up ranged from minimum of 14 months to maximum of 22 months and averaged 18.9 ± 2.24 months. Union time ranged from 4 months to 6 months with average of 4.56 ± 0.62 months. Most of the patients achieved union of fractures within 5 months (93%). (Significant statistically with p = 0.000). The complications in our patients which we encountered were traumatic nerve palsy (4 patients), iatrogenic nerve palsy (1 patient with lateral cutaneous nerve palsy from un injured side), superficial wound infection (2 patients) and implant backout (2 patients). There was no case of non union. Even the patients in which the implant backed-out had their fractures united with no further intervention. (Since the back out happened at the time when the fracture had consolidated enough to progress to full union). Radiological outcome was calculated at one year after the surgery using Matta's Radiographic criteria [3] (Table 1). 21 patients (70%) in our study had excellent or good radiological outcome at one year follow up and the difference was found statistically significant (p = 0.028,chi sq. test). Majority of our patient's i.e 90% had no or slight, intermittent pain one year after the surgery. (Significant statistically, p = 0.000). 93% of the patients in our study had 70% or more range of motion of the injured hip as compared to the contralateral normal hip and this difference was found statistically significant (p = 0.000) (Graph 1, Graph 2 and Graph 3).

In calculation all the movements i.e abduction, flexion, extension, internal rotation and external rotation were measured in degrees, summed up and expressed as percentage of the sum of degrees of motion of contra-lateral normal hip. Majority of our patient's i.e 77% walked un assisted, normally or with a slight limp. (Significant statistically, p = 003). The functional results were calculated using clinical grading system developed by Merle d, Aubigne and postel (1954) adopted by letournel and Judet [8] and modified by Matta [3]. 22 (= 73%) patients had excellent or good functional outcome at I year follow-up. This was statistically significant (p = 0.010). The mean score was 15.5 with SD = 1.96 (Table 2).

Discussion

Fractures of the acetabulum remain an enigma for the orthopaedic surgeon [3]. This 20 year old statement is still applicable in some developing countries like ours, due to lack of technical expertise and infrastructure. The trend is, however, changing because of easy access of information technology and international literature. The standardization of clinicoradiological evaluation, fracture classification, surgical approaches and fixation techniques of displaced acetabular fractures has resulted in achieving goal of preserving a functional, mobile and pain less hip joint [8,3]. The frequency of complications ranges from 5-20% [3]. A study by Olson, et al. has revealed that there is a marked alteration in the mechanics of load transmission across the hip after a fracture of the posterior wall of the acetabulum. These findings are consistent with the clinical observations of Rowe and Lowell that conservative management of large fractures of the posterior wall of acetabulum predisposes to hip arthtrosis [9,14].

Non operative management in acetabular fractures is often unsatisfactory as has been reported by spencer RF [15]. In his review of 25 patients with unilateral acetabular fractures managed non-operatively in traction, 17 patients showed no displacement on initial radiographs but later exhibited displacement, 7 patients had unsatisfactory results owing to a displaced posterior column fractures, osteoporosis, delayed diagnosis, early weight bearing. Reconstruction of comminuted posterior wall acetabular fractures by buttress plating can be expected to produce good results [16]. Judet R, Judet J and letournel E, 1964 [17] advised open reduction and internal fixation for all displaced fractures. In the present study the mean age in which acetabular reconstruction was done was 37.03 years (range 20-60 yrs). 70% of the patients were aged 40 years or less (3rd or 4th decade of life). Deo, et al. [18] in a review of 79 patients who had undergone operative treatment for acetabular fractures reported mean age of 36 years (range 16-81 yrs). KY Tan, et al. [19] in a retrospective study of 15 cases of operatively treated displaced acetabular fractures found mean age of 34.9 years (range 25-60 yrs).

In our study 22 patients (73.33%) were males and 8 (26.66%) were females. Because most of the patients in this study had suffered moderate to high energy trauma. This explains male preponderance as most of the men in this age group participate in outdoor activities in this region. Matta JM [3] 1996 reported 71% of his patients were males. Borrelli JR [20] reported that 73.33% were males and 26.66 were females. Sathappan SS, et al. [21] reported total of 30 patients who underwent surgical fixation for acetabular fractures. There were 9(30%) females and 21(70%) males) (Table 3). In these study 17 patients (56.66%) had fracture on the right side while as the other 13 patients (43.33%) had fracture on left side. Among them 18 patients (60%) had suffered road traffic accidents (RTA) and in rest 12 pts (40%) the injury was sustained due to fall from height, that signifies that majority of the patients sustained fractures due to road traffic accidents as is the trend nowadays with all the high energy fractures i.e an increasing incidence of road traffic accidents. Madhu R, et al. [22] reported in his study that road traffic accidents in 76% and fall from height in 24% was the cause of acetabular fractures. Raj Kumar SA, et al. [23] reported 68 cases of acetabular fractures, out of which 45 had sustained RTA and 23 cases were as a result of fall from height.

In our series in addition to acetabular fractures 11(36.66%) pts had associated injuries like chest trauma 3(10%) extremity trauma 8(26.66%). This is consistent with the study of Kumar A [23] where 37 (50%) of pts had associated injuries. The clinical results in patients with associated injuries have been reported to be similar to those with an isolated acetabular fracture (Matta JM 1996 [3], Liebbergall M, et al. 1999 [24]. In our study there were 20 cases (66.66%) of posterior wall fractures, 4 cases (13.33%) of posterior column fractures and 6 cases (20%) of posterior wall plus posterior column fractures. Posterior wall fractures (66.66%) constituted the major portion of the fractures in the study, which is comparable to Letournel E [12] and Gianoudis PV, et al. [2] studies.

All the patients were taken up for surgery within 2 weeks after sustaining the injury. The average interval between injury and surgery was 7.5 days. Shortest interval between injury and surgery in our study was 4 days and longest interval was 12 days (2pts). Deo [18] reviewed the epidemiology and complications of 79 patients who underwent operative treatment for acetabular fractures and the mean time interval between injury and surgery was 8.6 days (range of 1-16 days). Kumar A [23] in his study of 72 patients reported average time interval between injury and surgery was 11.7 days (range 1-35 days). 58 (80%) of cases were operated within 2 weeks after injury. In majority of patients, 21(70%), surgery was completed in 3 hours or less. The average duration of surgery was 2 hours 31 minutes (range 1 hour 40 minutes to 4 hours).

The operating time in our study is consistent with the study conducted by Lim HH, et al. [25], where operating time was less than 3 hours (2 hours and 20 minutes). The hospital stay averaged 14.43 days. All the patients were discharged by or before 22 days of admission. Kumar A, et al. [23] in their study found the mean hospital stay was 26.5 days. About 2/3rd of the patients were discharged within 3 weeks. Matta JM [3] reported mean duration of hospital stay of 19 days (3-137 days). The length of follow up ranged from minimum of 12 months to maximum of 22 months with an average of 18 months. Raj Kumar SA [23] in his study had minimum follow up period of 12 months with an average of 36 months (12-78 months).

In this study all the patients achieved union of fracture by 6 months. Union time ranged from 4-6 months with an average of 4.56 months. There was no non union reported in our study, thus consistent with the study of Helfet and Schmeling [26] who reported 0% non union rate in their series of 127 surgically treated acetabular fractures. Matta [3] also did not find any non union in his series of 259 acetabular fractures. It is an accepted fact that the functional results of the displaced acetabular fractures correlate well with the radiological out come and that open reduction is the best method to achieve this.In our series 21(70%) had excellent or good radiological out come, correlated well with the functional out come 22(75%)' Radiological outcome was calculated at one year after surgery using Matta's radiographic out come criteria [3].

The functional results were calculated using clinical grading system developed by Merle d. Aubigne and postel (1954) adopted by Letournel and Judet [8] and modified by Matta [3]. Overall, 75% i.e 22 out of 30 of our patients had excellent/good results (Matta score>15). Table 4, below compares our results with other reported series. All the patients were operated using Kocher-Langenbeck approach. This approach was chosen in view its excellent access to posterior wall and posterior column of acetabulum and great familiarity with this approach. The complications in our study included traumatic nerve palsy 4 cases (13.33%), superficial wound infection 2 cases (6.66%) and implant back out 2 cases (6.66%). 4 patients with traumatic nerve palsy had sciatic nerve involvement which recovered in subsequent follow ups (in 2 of them in 4 months after surgery, in one at 6 months and in one at 2 months). The patient with iatrogenic lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh involvement had the contralateral side i.e the normal side involved which was due to positioning of the patient mid prone during the surgery which lasted the longest (240 mins) in our study.

The patient had mild dysesthesia which disappeared after 2 months of surgery. Giannoudis, et al. [2] in a meta-analysis of 3670 acetabular fractures found incidence of traumatic nerve palsy of 16.4% and iatrogenic nerve palsy of 8%. The incidence of superficial wound infection in their study was 4.4%. 2 patients with implant backout had comminuted fractures. The patients had backout about 3 and 4 months after surgery, however, the fracture reduction was maintained and no further intervention was needed; the patients were having fair clinical results and were managing their daily activities of life. Stockle, et al. [27] found 3 cases (6%) of hardware backout in 50 patients of their study. Our review of 30 cases of posterior wall and or posterior column fractures showed that adequate reduction can be achieved in 75% of cases. This illustrates the high rate of success possible even in less established centres and compares well with the rate of successful reduction of 74% (Deo, et al.) [18] and 76% (Matta, et al.) [3].

Summary

The study entitled "Short term outcome in operative management of posterior wall and/or posterior column fractures of acetabulum" was conducted on 30 patients in SKIMS MEDICAL COLLEGE, Bemina between August 2014 to July 2015. The majority of the patients were males 73% (male to female ratio of 22:8) and the average age was 37.03 years. Majority of the patients had right side involvement (56.6%) with road traffic accident (60%) as the most common mode of injury followed by fall from height (40%). Isolated posterior wall fractures of the acetabulum were most common fractures in the present study and accounted for 66.6% of the cases (20 cases). In our study 37% patients (11 cases) had other associated injuries. All of our patients were operated within two weeks after sustaining the injury, with an average surgical time of 2 hours and 31 minutes and average hospital stay of 14.43 days. The complications in our study included traumatic nerve palsy 4 cases (13 %), iatrogenic nerve palsy 1 case (3.33%), hardware backout 2 cases (6.66%) and superficial wound infection 2 cases (6.66%). The patient with iatrogenic lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh involvement had the contralateral side i.e the normal side involved which was due to positioning of the patient mid prone during surgery which lasted the longest (240 mins) in our study.

The patient had mild dysesthesia which disappeared after 2 months of surgery. The patients with superficial wound infections got treated with intravenous antibiotics for 7 days. The patients with implant backout one having posterior wall fracture and the other isolated posterior column had hardware backout at 3 and 4 months after the surgery respectively. However, the fracture reduction was maintained and the patients had fair clinical results. Good to excellent results were achieved in three-fourths of our patients after 12 months follow up. The limitations of our study were small sample size of patients and short follow up of I year duration and this being first study of its kind in our institution, however, strength of this study was that the surgeries were carried out by two surgeons only and statistics were only from one institution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although fracture complication is often complex, satisfactory results were achievable in majority of cases. The operative management of these fractures is being preferred as complications,especially long term associated with conservative management are significant and associated with considerable morbidity. In essence the surgeon should prepare well for the problems like prolonged operating time and increased blood loss. Time spent on a thorough study of radiographs and a proper plan helps to outline an appropriate surgical technique and an appropriate type of implant.

References

- Anizar Faizia A, Hisam A, Sudhagar KP, et al. (2014) Outcome of surgical treatment for displaced acetabular fractures. Malays Orthop J 8: 1-6.

- Giannouds PV, Grotz MRW, Papakostidis C, et al. (2005) Operative treatment of displaced fractures of the acetabulum. Ameta analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 87: 2-9.

- Matta JM (1996) Fractures of the acetabulum: Accuracy of the reduction and clinical results in patients managed operatively with in three weeks after the injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78: 1632-1645.

- Kebaish AS, Roy A, Rennie W (1991) Displaced acetabular fractures: Long term follow up. J Trauma 31: 1539-1542.

- Matta JM, Merrit PO (1988) Displaced acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 230: 83-97.

- Matta JM, Mehne DK, Roffi R (1986) Fractures of the acetabulum. Early results of a prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 205: 241-250.

- Ragnarsson B, Mjoberg B (1992) Arthrosis after surgically treated acetabularfractures. A retrospective study of 60 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 63: 511-514.

- Letournel E, Judet R (1993) Fractures of the acetabulum, Edited by RA Elson. New York, Springer.

- Oslon SA, Bay BK, Chapman MW, et al. (1995) Biomechanical consequences of fracture and repair of posterior wall of acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77:1184-1192.

- Wright R, Barrett K, Christie MJ, et al. (1994) Acetabularfractures: Long term Follow up of open reduction and internal fixation. J Orthop Trauma 8: 397-403.

- Lehman W, Michael Hoffmann, Florian Fensky, et al. (2014) Frequency of nerve injuries associated with acetabular fractures, a prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472: 3395-403.

- Letournel E (1980) Acetabularfractures: Classification and management. Clin Orthop Relat Res 151: 81-106.

- Moed BR, Karges DE (1994) Prophylactic Indomethacin for the prevention of heterotopic ossification following acetabular fracture surgeryin high risk patients. J Orthop Trauma 8: 34-39.

- Rowe CR, Lowell JD (1961) Prognosis of fractures of acetabulum. JBJS (Am) 43: 30-59.

- Spencer RF (1989) Acetabular fractures in olde patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 71: 774-776.

- Ebraheim NA, Patil V, Liu J, et al. (2007) Reconstruction of communited posterior wall fractures using the buttress technique: A review of 32 fractures. Int Orthop 31: 671-675.

- Judet R, Judet J, Letournel E. (1964) Fractures of the acetabulum: Classification and Surgical approaches for open reduction. Preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 46: 1615-1646.

- Deo SD, Taveres SP, Pandey RK, et al. (2001) Operative management of acetabular fractures in Oxford. Injury 32: 581-586.

- Tan KY, Lee HC, Chua D (2003) Open reduction an internal fixation of fractures of the acetabulum-Local Experience. Singapore Med J 44: 404-409.

- Borrelli J, Goldfarb C, Catalano L, et al. (2002) Assessment of articular fragment displacement in acetabular fractures: A comparison of computerized tomography and plain radiographs. J Orthop Trauma 16: 449-456.

- Sathappan SS, CM Qi, A Pillai (2010) Surgical stabilization of pelvic and acetabular fractures. A review of determinants of clinical outcomes. Malaysian Orthpaedic Journal 4: 12-18.

- Madhu R, Kotnis R, Mousawi Al, et al. (2006) Outcome of surgery for reconstruction of fractures of the acetabulum. The time dependent effect of delay. J Bone Joint Surg Br 88:1107-1203.

- Kumar A, Shah NA, Kershaw SA, et al. (2005) Operative management of acetabularfractures: A review of 72 Fractures. Injury 36: 605-612.

- Liebergall M, Moshief R, Low J, et al. (1999) Acetabular fractures: Clinical outcome of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 366: 205-216.

- Lim HH, Tang CL, Krishnamoorthy S (1994) Operative treatment of acetabular fractures. Singapore Med J 35: 173-176.

- Helfet DL, Schmeling GJ (1994) Management of complex acetabular fractures through single on-extensile exposures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 305: 58-68.

- Stöckle U, Hoffmann R, Nittinger M, et al. (2000) Screw fixation of acetabular fractures. Int Orthop 24: 143-147.

- Heeg M, Klasen Hg, Visser JD (1990) Operative treatment of acetabular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 72: 383-338.

- Gupta RK, Sing H, Dev B, et al. (2009) Results of operative treatment of acetabular fractures from the third world-how local factors affect the out come. Int Orthop 33: 347-352.

Corresponding Author

Dr Jawed Bhat A, Professor Orthopaedics, SKIMS Medical College Srinagar, Chief Researcher, India, Tel: +91-778-096-6397.

Copyright

© 2021 Jawed BA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.