Esophageal Erosion Caused by Screw Displacement 22 Years after Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery

Abstract

Esophageal injuries can occur many years after anterior cervical surgery. This case reports an esophageal perforation caused by screw migration 22 years after anterior cervical fusion for a C5-C6 tear-drop fracture. Dysphagia was the main presenting symptom. Early diagnosis and a joint spine and general surgery allowed a successful management after hardware removal, esophageal repair and sternocleidomastoid muscle flap. Oral intake was resumed gradually. It should alert physicians to perform imaging studies for any dysphagia lasting more than 48 hours after surgery and emphasizes the need for a long-term follow-up.

Keywords

Esophageal perforation, Anterior cervical spine surgery, Dysphagia, Sternocleidomastoid muscle flap, Complication

Introduction

The anterior approach to the cervical spine is widely used since it was introduced in the 1950s by Cloward, Smith and Bailey [1-3]. The main indications for anterior cervical interbody fusion are instability, myelopathy, disc herniation, trauma and tumor. The design of plates and screws has constantly evolved to improve the fusion rate and to ensure immediate stability. However, postoperative complications may occur early, such as dysphagia, hematoma, and vocal cord paralysis [4] or later such as adjacent segment disease and esophageal perforation. This last stage complication can be resolved spontaneously or lead to deep infections, mediastinitis and death eventually [5]. The most common presenting symptoms are dysphagia (57%), neck swelling (21%) and pneumonia (11%). The average time for appearance of symptoms is 2.5 years and can occur up to 10 years after surgery [6]. Despite the few reports on this subject, the treatment of esophageal perforation remains controversial.

Herein, we describe the first case of extremely delayed esophageal erosion after protrusion of a locking screw, successfully managed with implant removal and sternocleidomastoid muscle flap.

Case Report

History

An 18-year-old man was admitted to a French trauma center in 1995 after a sport accident for a tear-drop fracture at C5-C6 level without neurological complication. He underwent a C5-C6 anterior decompression and interbody fusion using iliac crest autograft and C5-C7 fixation with Senegas plate and conventional screws without locking system (Synthes). The patient had an uneventful recovery. Nearly 22 years after surgery, the patient started to complain of neck pain and dysphagia.

Examination

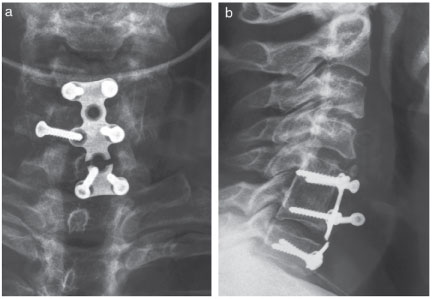

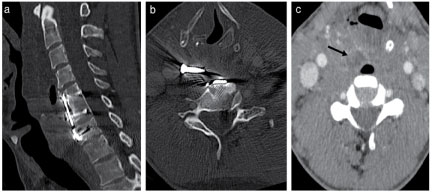

Because the symptoms worsened, he was examined by an ENT physician and an esophagoscopy revealed an immobility of the right hemi-larynx with no sign of perforation at this time. One months later, the patient developed 39° Celsius (= 102.2 °F) fever associated with severe dysphagia, voice changes and worsening neck pain. Cervical plain radiographs were performed and showed a broken plate at C6-C7 level, good fusion at C5-C6 level but non-union at C6-C7 with a migrated right-C6 screw (Figure 1). A contrast swallow radiograph of the esophagus showed a mobility of the screw facing the right part of C6 during swallowing, without stenosis or fistula. The patient was therefore admitted to our hospital where a CT-scan confirmed fusion at C5-C6 level, non-fusion at C6-C7 level and a plate breakage at C6-C7 level, with a migrated right-C6 screw in the retro-pharyngeal space and air in the soft-tissue anterior to C4-C5 and C6-C7 levels (Figure 2). Blood tests revealed elevated white blood cell counts and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) level was 240 mg/L.

Operation

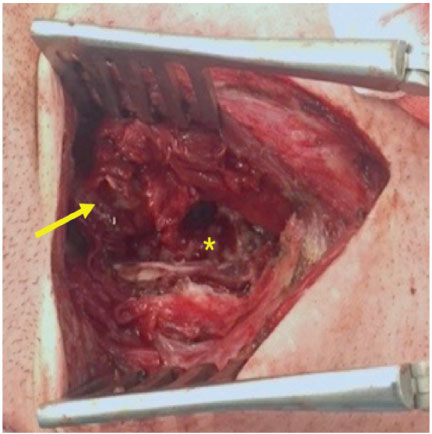

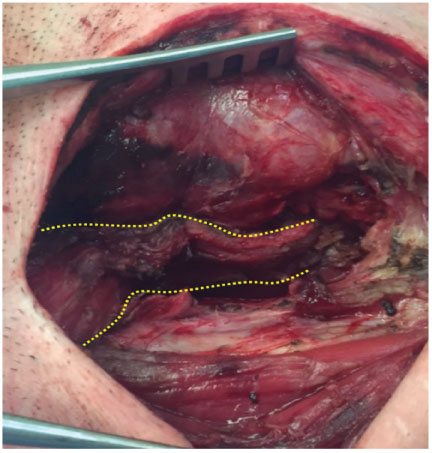

We discussed the case with general surgeons and because of the high risk of mediastinitis, we decided to perform a combined spine and general surgery. This operation was organized for the next morning, 24 hours after admission to our hospital. The original right anterolateral incision was used and extended. A nasogastric tube was placed. Several bacteriological samplings were taken. The plate and the five well-fixed screws were easily removed but the migrated right-C6 screw was more difficult to find because of its protrusion into the esophagus mucosa. We finally managed to take it out. There was no transfixing perforation of the esophagus and no leakage after blue methylene injection (Figure 3). We performed a wide debridement and the erosion was repaired by self-resorbing sutures. We decided to interpose a right pedicled sternocleidomastoid muscle flap between the esophagus and the cervical spine for a better closing (Figure 4). The skin was closed with a drainage tube.

Postoperative course

Postoperatively, we used a broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics therapy. Cultures were positive to Streptococcus pyogenes and an oral specific antibiotic therapy was administered for 45 days. The drainage tube was removed after 5 days and the bacteriological cultures on the drain at day-1, day-3 and day-5 were all negatives. The oral feeding was gradually resumed within 10 days and the patient was then discharged. Postoperative dynamics lateral radiographs of the cervical spine showed no instability and an MRI was performed at one-month follow-up and revealed no disc lesion at C6-C7 level and no sign of prevertebral infection. At the 3-month follow-up, the patient had an eventful recovery with persistent dysphonia under rehabilitation. At one-year follow-up, the evolution is very favorable with almost perfect recovery of the voice and no neck pain.

Discussion

Esophageal injury is a rare but dreaded complication after anterior cervical surgery with an overall incidence ranging from 0.2 to 3.4% [7-10]. Typical clinical presentation includes dysphagia, neck swelling, neck pain, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumonia and fever [6,11-17]. Dysphagia is a fairly common symptom after anterior cervical spine surgery, due to esophageal retraction for the cervical spine approach, but should normally regress within the first 48 hours. Less common symptoms are loss of weight and dyspnea [18]. Twenty-five percent of cases occurred within 3 months after surgery, 46% within 1 year and the average time for presentation was 2.5 years after surgery [6]. We found in the literature a reported case of esophageal perforation within 10 years after surgery [6]. The specificity of our case is the extreme late time of presentation after surgery: Nearly 22 years. In case of early perforation, most of symptoms could be present whereas late perforation, because of the healing from the external to the internal mucosa, may lead to dysphagia alone [6].

Reasons for esophageal perforation could be separated in non-surgical and surgical reasons. The main non-surgical reason is traumatic intubation. Early surgical causes are prolonged retraction of esophageal structures and sharp instruments leading to progressive necrosis of esophageal tissue [13]. Late surgical causes are instrumentation failure, screw migration, plate breakage, migration of bone graft [12,13,17] and could occur when the instrumentation is well fixed because of repetitive friction between the esophagus and the plate leading to esophageal necrosis [6,10]. In our case, it is interesting to note that C6-C7 level was instrumented but no discectomy and fusion were performed. The reason for that was not noted in the operative record but we can assume that the C5-C6 tear-drop fracture was associated to a fracture of the lower C6-facet joint without C6-C7 disc lesion and that they performed an additional fixation at C6-C7 level without fusion. The persistence of a mobile segment, even instrumented, under a fused level, associated with the absence of a locking screw system was the trigger for the plate breakage and the screw migration.

It should be noted that esophageal perforation related to anterior cervical spine surgery are more frequent in case of cervical trauma than in degenerative disorders [14]. The most involved levels are C5-C6 and C6-C7. It is suggested that the weakness of the lateral wall of the pyriform sinus and the thickness of the esophageal wall at C5-C6 where it lies directly on the cervical vertebra and is only covered by fascia at the dorsal side are the main reasons for its affection at these levels [6,13,14,16].

Esophageal perforation can rarely resolve spontaneously but the majority leads to local infection, spondylodiscitis, and may be life-threatening with mediastinitis and systemic sepsis. The mortality rate ranges from 4% to 50% [10,15].

The diagnostic tools are varied and useful in most cases. Lateral cervical radiographs can show direct sign such as instrumentation migration and indirect signs such as prevertebral air, subcutaneous emphysema and widening of the retropharyngo-esophageal space. Contrast swallow radiographs show fistula, stenosis and visualize location of the perforation and extension of extravasation [12]. But there is a risk to misjudge a lesion in case of perforation affecting the mucosa only [16]. Endoscopy can visualize a foreign body. Cervical CT-scans may detect instrumentation and migration failure, graft displacement, prevertebral abscess, prevertebral gas, mediastinitis and allow the evaluation of the bony fusion before surgery. Methylene blue injection in the esophageal lumen during surgery to visualize the perforation is controversial, as suggested by Nourbakhsh, et al. [6] but not helpful for Kau, et al. [9]. MRI can be helpful to reveal spondylodiscitis [6]. However, these investigations have a non-negligible false negative rate. Imaging studies indicated an esophageal injury in only 73% of perforations that were confirmed during surgery [7]. In case of strong clinical suspicion, surgery is warranted because early diagnosis and treatment is correlated to low morbidity and mortality. Mortality increases to 20% if treated within 1 day and to 50% if treatment is delayed [12].

The management of esophageal perforation remains controversial. The conservative medical treatment includes stopping oral intake, introducing parenteral alimentation, placing nasogastric tube and administrating broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy [11,12]. Unfortunately, 25% of patients treated conservatively developed an abscess [10-12] and the mortality rate was 18% [12]. Therefore, non-surgical treatment is recommended for small erosion less than 1 cm [11,19,20].

The surgical treatment includes implant removal if necessary, wide debridement of infected tissues, bacteriological sampling, esophageal repair and drainage [6,9,14]. When instability is expected, external immobilization is necessary before posterior cervical fixation which can be performed after long-term antibiotic therapy [13,17]. In case of perioperative esophageal lesion, closure of perforation with suture is indicated [13], sometimes associated with a pedicled muscle flap interposition. Indications to flaps are severe infection, delayed lesion when there is a need to leave the instrumentation, suture failure [11] and large perforation [9,11,16,18]. The most common technique is the sternocleidomastoid muscle flap, but its use is controversial because of the risk of tissue necrosis and loss of cervical motion [18]. In case of neurological deficit where neck movement is important, the pectoralis major flap seems to be more relevant to minimize loss of cervical motion [9,18]. The longus colli muscle flap appears to be another alternative solution of soft tissue coverage, with the risk to injure the cervical sympathetic trunk [14]. In case of large segmental esophageal loss, the free jejunal flap should be a solution in this complex situation [15].

The author's recommendations for the prevention of esophageal perforation during surgery are the careful placement of retractor blades and gentle tissue handling [13], using a low profile and smooth plate [8] with locking screw system to prevent the back out [21]. We must avoid instrumenting a spine segment without associated fusion because it promotes the risk of implant failure, unless removal is planned. After esophageal repair, a control-esophagogram is mandatory before resuming oral feeding [12]. Finally, the patient should be informed of the possible complications after anterior cervical surgery and every dysphagia lasting more than 48 hours after surgery should alert the physician and be investigated [6,22].

Conclusion

This case of delayed esophageal erosion 22 years after anterior cervical spine surgery reminds us that complications can occur even decades after surgery and that a long-term follow-up is necessary. Early diagnosis and treatment improve the survival rate. Stopping oral intake associated with surgical treatment included hardware removal, wide debridement, esophageal repair, pedicled muscle flap coverage and antibiotic therapy are the key points of treatment.

Financial Support

We have no financial support. This paper has not been yet presented or published previously.

References

- Cloward RB (2007) The anterior approach for removal of ruptured cervical disks. 1958. J Neurosurg Spine 6: 496-511.

- Smith GW, Robinson RA (1958) The treatment of certain cervical-spine disorders by anterior removal of the intervertebral disc and interbody fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 40: 607-624.

- Bailey RW, Badgley CE (1960) Stabilization of the cervical spine by anterior fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 42-42: 565-594.

- Campbell PG, Yadla S, Malone J, et al. (2010) Early complications related to approach in cervical spine surgery: single-center prospective study. World Neurosurg 74: 363-368.

- Chataigner H, Gangloff S, Onimus M (1997) Spontaneous elimination by the natural tracts of screws of anterior cervical osteosynthesis. Apropos of a case. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 83: 78-82.

- Nourbakhsh A, Garges KJ (2007) Esophageal perforation with a locking screw: a case report and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 32: E428-E435.

- Gaudinez RF, English GM, Gebhard JS, et al. (2000) Esophageal perforations after anterior cervical surgery. J Spinal Disord 13: 77-84.

- Carucci LR, Turner MA, Yeatman CF (2015) Dysphagia Secondary to Anterior Cervical Fusion: Radiologic Evaluation and Findings in 74 Patients. Am J Roentgenol 204: 768-775.

- Kau RL, Kim N, Hinni ML, et al. (2010) Repair of esophageal perforation due to anterior cervical spine instrumentation. Laryngoscope 120: 739-742.

- Leaver N, Colby A, Appleton N, et al. (2015) Oesophageal perforation caused by screw displacement 16 months following anterior cervical spine fixation. BMJ Case Rep 20.

- Solerio D, Ruffini E, Gargiulo G, et al. (2008) Successful surgical management of a delayed pharyngo-esophageal perforation after anterior cervical spine plating. Eur Spine J 17: 280-284.

- Orlando ER, Caroli E, Ferrante L (2003) Management of the cervical esophagus and hypofarinx perforations complicating anterior cervical spine surgery. Spine 28: 290-295.

- Ardon H, Van Calenbergh F, Van Raemdonck D, et al. (2009) Oesophageal perforation after anterior cervical surgery: management in four patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 151: 297-302.

- Haku T, Okuda S 'ya, Kanematsu F, et al. (2008) Repair of cervical esophageal perforation using longus colli muscle flap: a case report of a patient with cervical spinal cord injury. Spine J 8: 831-835.

- Küntscher MV, Erdmann D, Boltze W-H, et al. (2003) Use of a free jejunal graft for oesophageal reconstruction following perforation after cervical spine surgery: case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord 41: 543-548.

- Lu X, Guo Q, Ni B (2012) Esophagus perforation complicating anterior cervical spine surgery. Eur Spine J 21: 172-177.

- Yin D, Yang X, Huang Q, et al. (2015) Pharyngoesophageal perforation 3 years after anterior cervical spine surgery: a rare case report and literature review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 272: 2077-2082.

- Pichler W, Maier A, Rappl T, et al. (2006) Delayed hypopharyngeal and esophageal perforation after anterior spinal fusion: primary repair reinforced by pedicled pectoralis major flap. Spine 31: 268-270.

- Yee GK, Terry AF (1993) Esophageal penetration by an anterior cervical fixation device. A case report. Spine 18: 522-527.

- Yang S-Y, Lee S-B, Cho K-S (2015) Delayed Esophagus Perforation after Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery. Korean J Neurotrauma 11: 191-194.

- Fogel GR, McDonnell MF (2005) Surgical treatment of dysphagia after anterior cervical interbody fusion. Spine J 5: 140-144.

- Welsh LW, Welsh JJ, Chinnici JC (1987) Dysphagia due to cervical spine surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 96: 112-115.

Corresponding Author

N Barut, Orthopedic and Trauma Surgery Department, 47-83 Boulevard de l'Hôpital, La Pitié-Salpétriêre Hospital, University Paris 6, Paris, France, Tel: +33-142-177-535, Fax: +33-142-177-415.

Copyright

© 2019 Barut N, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.