Suture Derived Foreign Bodies in Ophthalmic Surgery

Abstract

Usually swaged end suture attachments to the needles are preferred providing most atraumatic suturing possible. However, we report on the possible release of foreign material from sutures whilst performing penetrating glaucoma surgery (trabeculectomy). In this surgery any release of foreign material would have imposed a significant risk on the success of surgery and the health of the eye. The foreign bodies were less than 100 μm in size and very difficult to see without the microscope. As we consider these incidents potentially hazardous but easily avoidable, we urge our fellow surgeons, to carefully examine the surgical tools and sutures carefully prior and after surgery. The key sign of a faulty suture attachment is an enhanced resistance when pulling the needle through the tissue such as the sclera. The additional force exerted to pull the needle through is enough to deliberate foreign material. Any foreign body left behind in the wound has the potential to put the success of any surgery at risk.

Introduction

In today's ophthalmic surgery the surgeon relies on the quality of suture material. The desired characteristics of sutures used vary depending on location and purpose in various aspects such as expected tensile strength, thickness, color, needle form and length etc [1]. One of the highest demands is, however, the expectation that the material causes only minimal local inflammation and, most of all, does not to leave any residues within the wound. The specific demands on sutures have been identified and outlined in a specific guidance document, published by the FDA 2003 [2]. The desired properties determine the choice of the suture. The plethoras of available properties have been reviewed recently and include, amongst others tensile strength, diameter, tissue absorption, coefficient of friction, knot security and strength, elasticity and plasticity [3]. Sutures have become high-tec products and have to be considered as temporary implants. With this they are often not just neutral foreign bodies but may, for example due to their possible content of residual metal catalysts, also cause unwanted side effects, such as inflammation [4]. Still, in spite of rigorous technical product checks (such as quality inspection and multistep inspections of raw materials as well as technology in-process inspections, it is apparently still possible that foreign substances might be introduced by sutures and released in the operation field, as this reports shows. Apparently, glues used to attach the needle to the suture material may be amongst these agents. Release of such larger particles from suture material has, so far, and to the best of our knowledge, not been reported. Glues as materials, often contain raisin, such as polyepoxy adhesive [5], which can be potentially toxic or prone to cause additional inflammation. Also, could the process of covalent bonding of cyanoacrylate and methacrylate resins by copolymerization, explored extensively in dentistry [6], deliberate substances that could, if not eliminated cause or sustain inflammation. Reported toxicity of cyanoacrylate may manifest as conditions such as urticaria, contact dermatitis and other dermatoses [7]. The suture material itself by its chemical composition is less likely to cause inflammation, if produced according to the protocols. Reactions may occur but are usually only very minor. In general are ophthalmic surgeons extremely dependent on the quality of the suture material, they rely on them heavily as their performance and high-tec reliability often is the key to even conduct some surgeries. As in all microsurgery, sutures are often very difficult to put into position and not seldom the surgeon only has one single chance to set the suture right. This outlines the importance of our observation when we report on the release of foreign bodies form suture material during glaucoma surgery in three cases.

Cases

Case 1

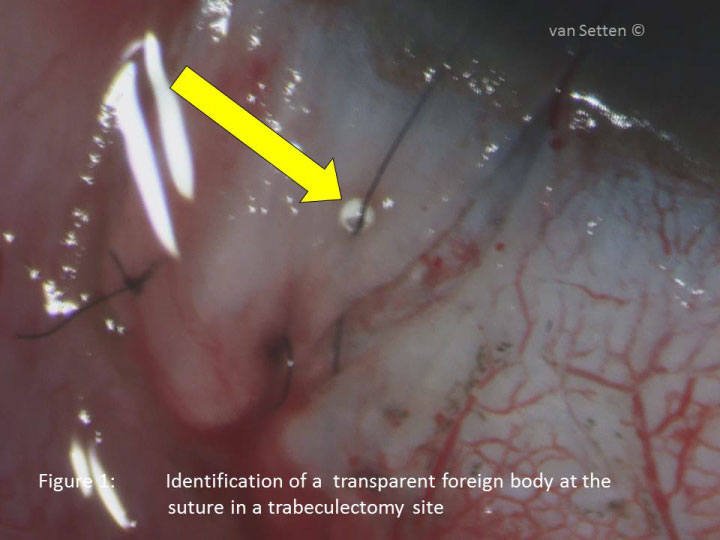

In the final phase of a trabeculectomy as usual a commercially available 10-0 nylon suture (dyed in black, Company and Product™ name deleted due to legal aspects ) was used to re-adapt the scleral flap. The suture comes as double armed suture and is cut in the middle prior to it's use in the eye. The first part of the suture was placed uneventfully in place. The second half of the suture was passed through the scleral flap with a feeling of an unusual resistance when the needle passed through. Inspection of the scleral flap at the entrance site of the suture revealed the presence of a clear pear like foreign body around the black nylon suture (Figure 1). The foreign body was removed and inspected later on the microscope (Figure 2). It was of hard consistency, round shaped and in absence of on the other source of the region must have been introduced with the suture material. Alerted by this incident close attention was placed to the following sutures of the same origin. During the same day no further foreign bodies were discovered around or in association with sutures.

Case 2

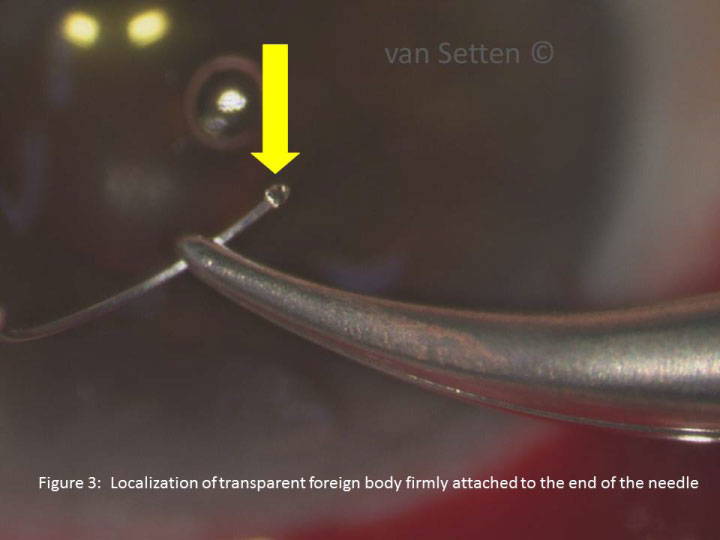

Shortly after case 1 a fresh unused suture (Company and Product™ name deleted due to legal aspects) was used. Again, as usual, it was divided into two by a cut in the middle. Then the first part was used uneventfully whereas the second part of the suture went off just behind the needle prior to use. Alerted by the previous incident the needle and suture were inspected under the microscope. Here, at the end of the needle there where the suture had come off a similar pearl was discovered (Figure 3).

Case 3

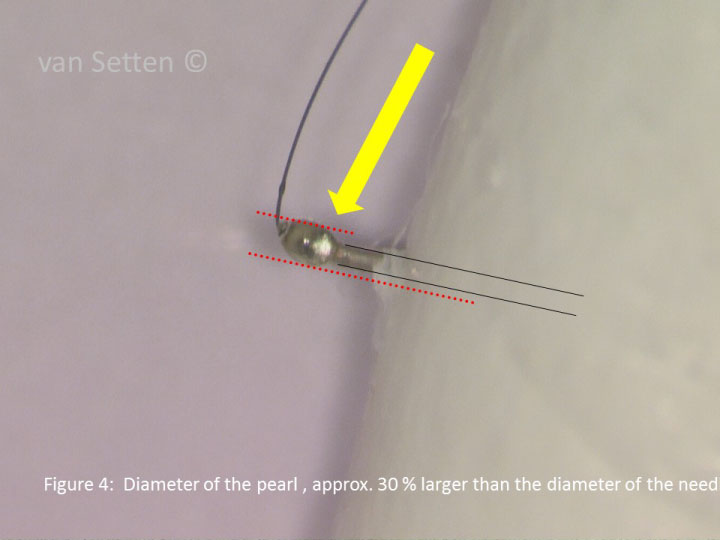

A year after the cases one and two the same resistance was observed when suturing a scleral flap. It was at the end of an uneventful surgery, until when trying to pull the needle through the scleral flap, the resistance was so strong that the needle had to be taken out reversed and to be visually expected. Also here a fresh unused suture of the same kind and make (Company and Product™ name deleted due to legal aspects) was used. Here, the same material as in cases 1 & 2 was discovered, looking like a miniature translucent olive, exceeding the diameter of the needle with approximately 30% (Figure 4). The other end of the suture the suture material was swaged into the needle.

Discussion

The techniques of attaching sutures to needles are usually not the surgeons concern as we rely on the sophisticated manufacturing processes and regulations. Additionally are most of these techniques intellectual property, as such protected by patent laws and seldom revealed or discussed in public. The available data and case reports touching this issue are hence minimal. Similarly, these matters are usually not the surgeons concern. However, the present cases reveal a different reality. According to US3981307A US patent application surgical sutures are attached to needles by mechanically clamping or by applying a suitable liquid adhesive to the end of the suture before inserting the suture end into a hole in the blunt end of the needle. The idea to use adhesives to join needles and sutures is not new [5] but has been optimized throughout the years with new materials coming into existence. Nevertheless, in the process of applying adhesives, the proper curing or hardening of the liquid adhesive compound is required to hold the suture firmly in place. In this process the adhesive compound may not always cure to proper hardness, creating a weakened bond or may be dislodged. With such attachments a technique of reattachment as recently suggested by Tillo [8] is not possible. When using adhesives, in order to optimize their adhesion to the material additional special preparation of the suture tip and the needle may be required. In the present cases the diligence of this processes, or their realization, apparently was not sufficient and the adhesive did come off. As these materials are not intended to be released or remain in the wound and especially not in the eye the observed incidents do deserve our total attention. As stated above apparently the manufacturing methods are responsible for this plastic or resin like material to remain in some of this sutures at place, there where the suture material is attached to the needle. It must be emphasized that the observed issues did occur only occasionally but repeatedly and only with the 10-0 nylon suture. As to the best of the surgeons' knowledge the foreign bodies released from the suture have always been identified and recovered. We can therefore only speculate about the sequelae a foreign body can cause if left in the eye. The resulting scenario reaches from an inert encapsulated foreign body leaving the surrounding totally unharmed and silent to the possibility of significant inflammation threatening not only the result of surgery but also the eye itself. In all cases, the postoperative course was totally uneventful. However, due to the observations made and if not done routinely already, fellow surgeons are encouraged to carefully look at these insertion points prior to applying the suture in the tissue. Increased resistance of the needle passing through tissue is a hallmark for the presence of material attached to the suture or needle that is not the intended or desired to be there. The force required for needle penetration through a target material should be only related to the needle wire diameter and its hardness [9]. As the needle wire diameter should be the largest diameter of the entire suture, including the needle, any component on the needle increasing this diameter is not acceptable. Any material on the suture larger in size than the largest wire or needle diameter in the patient's eye does impose a significant risk of introducing foreign bodies of unknown nature into the operation field. Especially in glaucoma surgery where any fibrotic reaction or inflammation is highly undesirable no foreign body or agent left in the operation area, possibly introducing inflammatory reactions, can be acceptable [10].

It is concluded that, in spite of high demands on suture material it is apparently still possible that foreign bodies might be introduced into the operation field by sutures. Ophthalmic surgeons have this fortune to be able to inspect any suture material under the microscope for the presence of such material on the sutures prior to the application of it in the wound. It is urgently recommended that any unusual resistance during the use of sutures should lead to immediate inspection of the sutures in the search for foreign material.

Acknowledgement

The support and help in technical issues of the Aviation-Ophthalmology Inc., Danderyd, Sweden is gratefully acknowledged.

The company of the product is acknowledged for their interest in the events presented here and for their feed back after receipt of the information. As the company was pointing out not be able" to give any guarantee to you or the publishers regarding the possible legal consequences of the publication of your article at the present time", the company name is not mentioned or disclosed.

References

- Chu CC (2013) Materials for absorbable and nonabsorbable surgical sutures. In: Martin W. King, Bhupender S. Gupta and Robert Guido, Biotextiles as Medical Implants. Woodhead Publishing, 275-334.

- (2003) US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health: Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Class II Special Controls Guidance Document: Surgical Sutures; Guidance for Industry and FDA.

- Dart AJ, Dart CM (2011) Suture material: Conventional and stimuli responsive. Comprehensive Biomaterials 6: 573-587.

- Chu CC (2013) Types and properties of surgical sutures. In: Martin W. King, Bhupender S. Gupta and Robert Guido, Biotextiles as Medical Implants. Woodhead Publishing, 231-273.

- Hayworth D, Forbes S, Mathams JA (1957) US patent Application. Serial No. 669,401, US States Patent Office.

- Antonucci JM, Bowen RL (1977) Adhesive bonding of various materials to hard tooth tissues: xiii synthesis of a polyfunctional surface-active amine accelerator. J Dent Res 56: 937-942.

- Leggat PA, Kedjarune U, Smith DR (2004) Toxicity of cyanoacrylate adhesives and their occupational impacts for dental staff. Ind Health 42: 207-211

- Tillo O (2014) Reattaching the surgical thread to a needle: a problem solved. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 96: 560-561.

- Von Fraunhofer JA, Storey RJ, Masterson BJ (1999) Characterization of surgical needles. Biomaterials 9: 281-284

- Granger RN, Kassim MS (1989) Method for attaching a surgical needle to a suture. US patent Application 1989-09-27, App/Pub Number US07791075, 1991-11-12

Corresponding Author

Gysbert-Botho van Setten, MD, PhD, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Karolinska Institutet, St Eriks Eye Hospital, Polhemsgatan 50, 11282 Stockholm, Sweden

Copyright

© 2019 Gysbert -Botho van Setten. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.