Spontaneous Unilateral Triplet Interstitial Ectopic Gestation: A Case Report

Abstract

Background: Unilateral multiple ectopic gestations are very rare, and usually associated with in vitro fertilization as has been reported in studies. Unilateral twin ectopic gestation occurs in about 1 in 200 ectopic gestations. Unilateral triplet ectopic gestation is even more rare.

Case presentation: She was a 41-year-old G9 P4+4 (all alive), who presented to us with ruptured left interstitial ectopic gestation. Pregnancy was spontaneously conceived. Intraoperative findings included haemoperitoneum of 500 ml and triplet gestational sacs with a ruptured left interstitium. The right fallopian tube and both ovaries were grossly normal. She subsequently had left cornual wedge resection for ruptured left interstitial triplet ectopic gestation. Estimated blood loss at surgery was 400 ml.

Conclusion: The maternal morbidity and mortality associated with ectopic gestation can be mitigated by prevention and prompt treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease, provision of safe abortion and family planning services, early hospital presentation, a high index of suspicion by the attending physician, presence of diagnostic facilities, functional blood bank services and a standard operating theatre.

Keywords

Unilateral, Triplet, Interstitial, Ectopic gestation, Haemoperitoneum, Wedge resection

Introduction

Ectopic gestation is the implantation of a fertilized ovum at any site different from the uterine endometrium. It complicates 0.25%-2% of all pregnancies, globally [1-3]. In our environment, one of the commonest causes of maternal mortality in the first trimester of pregnancy is ectopic gestation. The mortality rate following ectopic gestation in our Centre is 3.3% [4]. This is within the range of 1%-6% reported within and outside Nigeria [5-8].

Unilateral multiple ectopic gestations are very rare, and usually associated with in vitro fertilization [9-11]. Unilateral twin ectopic gestation occurs in about 1 in 200 ectopic gestations. Unilateral triplet ectopic gestation is even more rare. Spontaneous interstitial gestation complicates 2%-6% of all ectopic gestations, with an incidence of 1 in 2,500-5,000 live births [12]. Although very rare, unilateral triplet ectopic gestation has been reported by Berkes, et al. following in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer [13].

Case Presentation

She was a 41-year-old G9 P4+4 (all alive), who presented to our gynaecological clinic for an expert opinion following two previous conflicting pregnancy reports on ultrasound scan. Pregnancy was spontaneously conceived, although she was unsure of her last menstrual period. She had no signs and symptoms. She has not been previously managed for pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic gestation, had surgery or any fertility treatment. Her vital signs were stable. She was a known hypertensive with poor drug compliance.

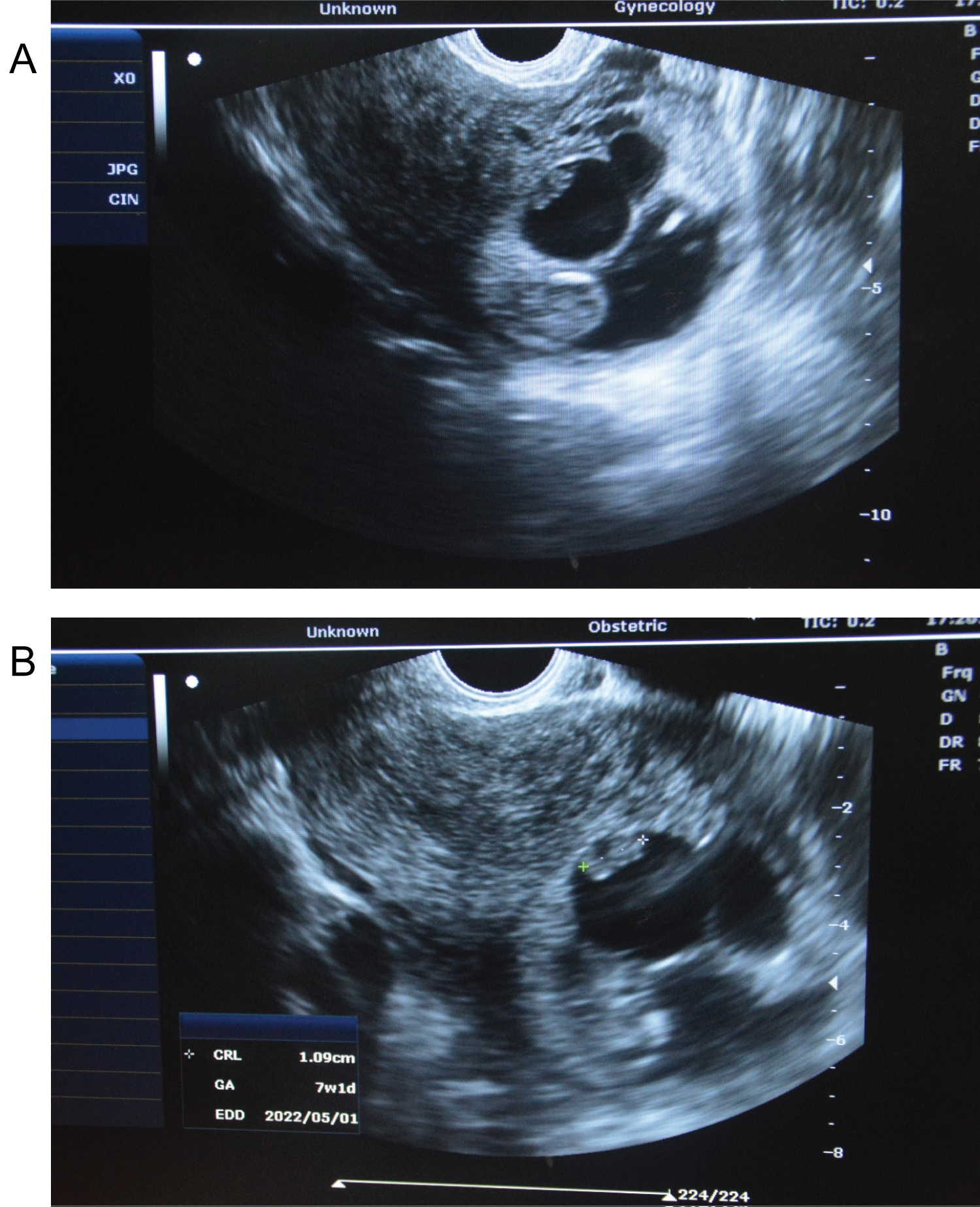

A confirmatory transvaginal ultrasound scan done revealed a left sided triplet ectopic gestation. The largest (first) sac contained an active embryo with CRL of 48 mm corresponding to a gestational age of 12 weeks (Figure 1a). The second sac contained a missed abortion at 7 weeks' gestational age (Figure 1b). The third sac was anembryonic (Figure 1a and Figure 1b).

She was counselled for surgery, but declined. She however, presented a few hours later with symptoms of abdominal pain, dizziness and a fainting spell. Her pulse was 86 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 20 cycles per minute, blood pressure was 140/100 mmHg, and temperature was 37 °C. Her packed cell volume was 35%.

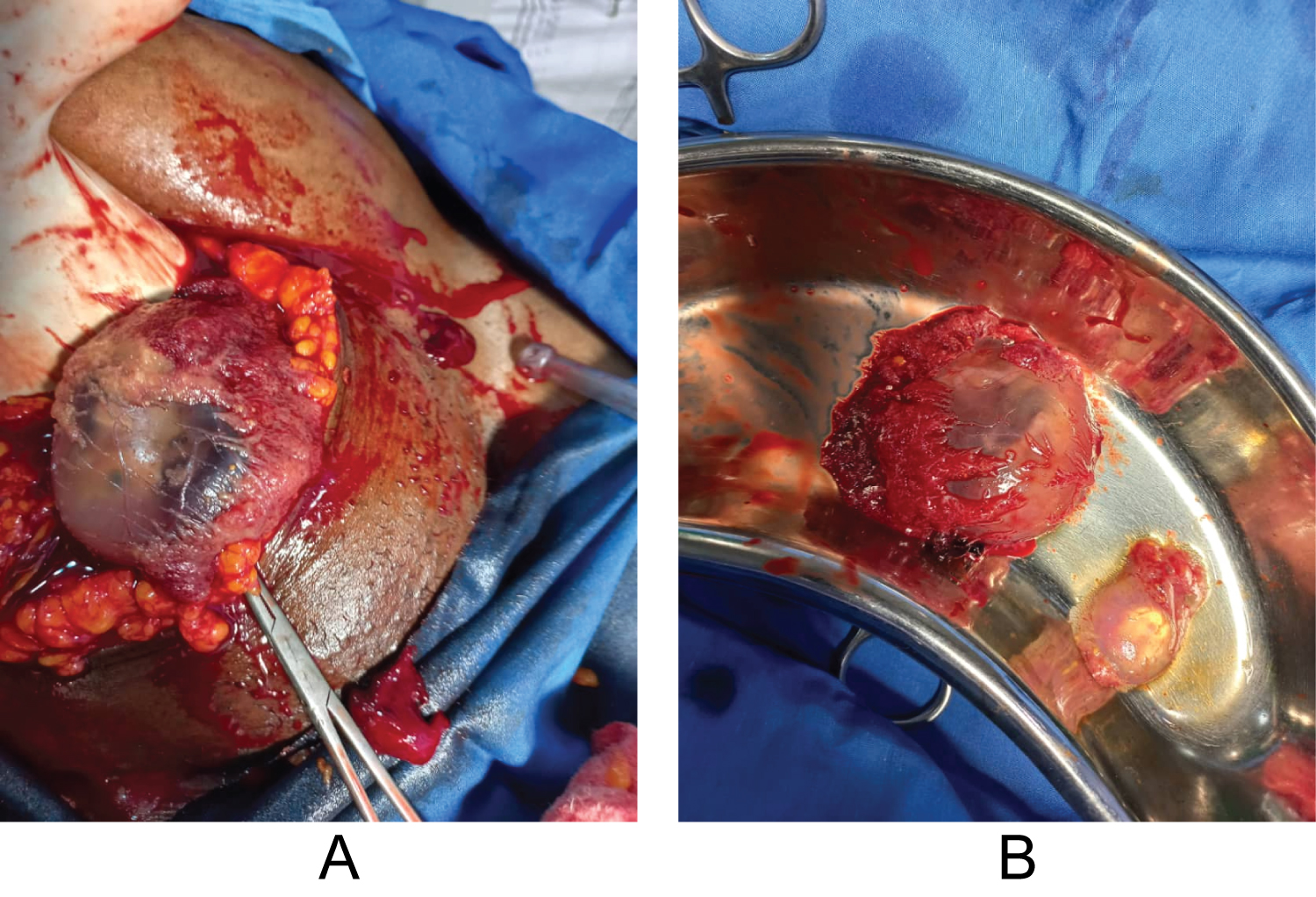

A diagnosis of ruptured unilateral triplet ectopic gestation was made. She and her husband were counselled on the findings, diagnosis, possible complications and the need for emergency laparotomy, which they consented to. Intraoperative findings included haemoperitoneum of 500 ml and triplet gestational sacs with a ruptured left interstitium (Figure 2a and Figure 2b). The right fallopian tube and both ovaries were grossly normal. She subsequently had left cornual wedge resection for ruptured left interstitial triplet ectopic gestation. Estimated blood loss at surgery was 400 ml.

Her post-operative packed cell volume was 30%. The histological examination confirmed triplet interstitial ectopic gestation. She was discharged home on the fifth post-operative day on haematinics after counselling on the impact of a cornual wedge resection on further pregnancy. She was then counselled on contraceptives to prevent possible maternal mortality from uterine rupture in a subsequent pregnancy. At her follow-up visit in two weeks, the abdominal wound had healed satisfactorily and her packed cell volume was 32%.

Discussion

Ectopic gestation is one of the commonest gynaecological surgical emergencies in the developing sub-Saharan Africa [14]. In our environment, ruptured ectopic gestation is more common (95.7%) compared to unruptured ectopic gestation (4.3%) [15]. The incidence of ectopic gestation is increasing in developing countries [14]. This may be due to improved management of pelvic inflammatory diseases which reduces rate of tubal blockage, but leaves the tubes with luminal damage; surgical treatment of damaged fallopian tubes; improved diagnostic techniques to diagnose unruptured ectopic gestation, where it may have been aborted naturally or reabsorbed [14].

The risk factor for ectopic gestation is from any condition that causes the disruption of the normal tubal anatomy like infections, surgery, congenital anomalies or tumours. The risk factor noticed in the patient presented was four previous induced miscarriages. Her age also predisposed her to having a triplet pregnancy. Other risk factors for ectopic gestation include pelvic inflammatory disease, previous ectopic pregnancy, history of infertility, conception following ovulation induction/in vitro fertilization + embryo transfer, previous pelvic surgery, multiple sexual partners, in-utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol and excessively long fallopian tube. The commonest site of ectopic gestation is the fallopian tube, where it occurs in about 96% of cases [16,17]. It occurred in the interstitium in the patient presented. Other sites are the abdominal cavity, ovary, broad ligament, cervix uteri and Caesarean section scar. Interstitial pregnancies are prone to severe haemorrhage due to the rich vascular anastomosis at the cornual region of the uterus. Patients who have had wedge resection following interstitial gestations are at high-risk of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies. Therefore, these patients must be counselled after the surgery about this possibility.

The diagnosis of ectopic gestation requires a high index of suspicion, with history, physical examination and a positive pregnancy test [18]. They usually present with complaints of abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding and amenorrhoea. Transvaginal ultrasound scan is important in the diagnosis of ectopic gestation, as it has been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity. These were shown in the ultrasound scan diagnosis of the patient presented.

The management of ectopic gestation may be expectant, medical or surgical, and it is dependent on whether it is ruptured or unruptured, clinical state of the patient, site of the ectopic gestation, the fertility desire of the patient and the management facilities on ground. The patient presented had ruptured left triplet interstitial ectopic gestation. She had surgical management which included emergency laparotomy with cornual wedge resection. Laparoscopy is another surgical route of management. Other procedures that can be done through these surgical routes are salpingectomy which may be partial or total, salpingotomy, salpingostomy, segmental resection and end-to-end anastomosis and manual expression.

Medical and expectant management protocols are usually carried out for unruptured ectopic gestation. Medical treatment includes the use of systemic drugs like methotrexate, actinomycin D, prostaglandins and mifepristone. Ultrasound and laparoscopically directed aspiration and/or local injection of 20% potassium chloride, 50% glucose, methotrexate, adrenalin and prostaglandin E and F into the ectopic gestational sac have been described [14,19]. Expectant management follows the natural history of ectopic gestation; and this method of management is unreliable, as failure rate is high [18].

The maternal morbidity and mortality associated with ectopic gestation can be mitigated by prevention and prompt treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease, provision of safe abortion and family planning services, early hospital presentation, a high index of suspicion by the attending physician, presence of diagnostic facilities, functional blood bank services and a standard operating theatre.

References

- Joshua HB, Edward MB, Hillson C (2014) Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Am Acad Fam Physician 90: 34-40.

- Rana P, Singh R, Afzal M, et al. (2013) Ectopic pregnancy: A review. Arch Gynaecol Obstet 288: 747-757.

- Yakassai IA, Abdullahi J, Abubakar IS (2012) Management of ectopic pregnancy in Aminu Kano teaching hospital, Kano, Nigeria. Glo Adv Res J Med Med Sci 1: 181-185.

- Osegi N, Omietimi J, Obagah L, et al. (2020) Ectopic pregnancy: A 10-year review in a tertiary hospital in South-South, Nigeria. Int J Res Rep Gynaecol 3: 41-46.

- Lawani OL, Anozie OB, Ezeonu PO (2013) Ectopic pregnancy: A life-threatening gynecological emergency. Int J Women’s Health 5: 515-521.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010) Ectopic Pregnancy Mortality - Florida, 2009-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

- Anderson FWJ, Hogan JG, Ansbacher R (2004) Sudden death: Ectopic pregnancy mortality. Obstet Gynecol 103: 1218-1223.

- Aboyeji AP, Fawole AA, Ijaiya MA (2002) Trends in ectopic pregnancy in Ilorin Nigeria. Niger J Surg Res 4: 1-2.

- Felekis T, Akrivis C, Tsirkas P, et al. (2014) Heterotopic triplet pregnancy after invitro fertilization with favorable outcome of the intrauterine twin pregnancy subsequent to surgical treatment of the tubal pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2014: 356131.

- Nikolaou DS, Lavery S, Bevan R, et al. (2002) Triplet heterotopic pregnancy with an intrauterinemonochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy and an interstitial pregnancy following invitro fertilisation and transfer of two embryos. J Obstet Gynaecol 22: 94-95.

- Tal J, Haddad S, Gordon N, et al. (1996) Heterotopic pregnancy after ovulation induction and assisted reproductive technologies: A literature review from 1971 to 1993. Fertil Steril 66: 1-12.

- Ophir E, Singer-Jordan J, Oettinger M, et al. (2004) Uterine artery embolization for management of interstitial twin ectopic pregnancy: Case report. Hum Reprod 19: 1774-1777.

- Berkes E, Szendei G, Csabay L, et al. (2008) Unilateral triplet ectopic pregnancy after invitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 90: e17-e20.

- Kwawukume EY, Idrisa A, Ekele BA (2015) Ectopic Pregnancy. In: Kwawukume EY, Ekele BA, Danso KA, et al. Comprehensive obstetrics in the tropics. (2nd edn) Accra, Ghana: Assemblies of God Literature Centre Limited, 282-288.

- John CO, Alegbeleye JO (2016) Ectopic pregnancy experience in a health facility in South-South Nigerian. Niger Health J 16: 14-16.

- Togas T (2021) Ectopic pregnancy: Epidemiology, risk factors and anatomic sites.

- Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, et al. (2002) Sites of ectopic pregnancy: A 10-year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod 17: 3224-3230.

- Njoku C, Oriji PC, Aigere EOS, et al. (2019) Spontaneous bilateral ectopic pregnancy: A case report. Yen Med J 1: 56-60.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2008) ACOG practice bulletin No. 94: Medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 111: 1479-1485.

Corresponding Author

Dr. Enefia Kelvin Kiridi, Department of Radiology, Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Okolobiri, Bayelsa State, Nigeria; Silhouette Radio Diagnostic Consultants, Yenagoa, Bayelsa State, Nigeria, Tel: 234-80-3724-9828

Copyright

© 2022 Oriji PC, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.