Acute Epiglottitis in a Patient with COVID-19 and C1 Esterase Deficiency: A Case Report

Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been associated with the rare, yet potentially fatal, condition known as epiglottitis. Epiglottitis has the potential to lead to complete airway obstruction, and often constitutes emergent management. Here, we describe a case of acute epiglottitis in a 19-year-old man infected with COVID-19 with a past history of angioedema. We discuss the management of this emergent condition, as well as the differential diagnosis and various management complexities inherent in patients presenting with epiglottitis in this new age of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords

COVID-19, Epiglottitis, C1 esterase deficiency

Abbreviations

ACE: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; CT: Computed Tomography; ED: Emergency Department; HAE: Hereditary Acquired Angioedema; HNS: Head & Neck Surgeon; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; HIPAA: Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act

Introduction

Epiglottitis is an uncommon disease of inflammation and swelling of the epiglottis and surrounding supraglottic structures [1] and is characterized by fever, pharyngitis, dysphagia, and dyspnea [2]. Epiglottitis has the potential to be fatal due to the possibility of rapid progression to life-threatening upper airway obstruction [3]. In the setting of epiglottitis with upper airway obstruction, airway management is critical to prevent further complications or fatality [4]. Epiglottitis has become less prevalent amongst adult patients over time due to widespread vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) -- the most common isolated pathogen in cases of epiglottitis. However, the proportion of epiglottitis cases caused by other pathogens has increased over time [5].

During the past three years, there have been multiple reported cases of adult epiglottitis associated with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [5-10]. COVID-19 may present with a wide range of symptoms, including respiratory symptoms such as cough and dyspnea [11]. As of March 2022, there have been over 453 million global cases and 5.9 million deaths due to COVID-19 [12]. Due to the widespread prevalence of COVID-19 in the current clinical environment, it is imperative for clinicians to be aware of potentially emergent and/or potentially fatal sequelae of the COVID-19 infection. This case reports describes a 19-year-old man who was brought to the operating room for emergent intubation as a result of epiglottitis presumptively associated with COVID-19. The patient and his family has provided written consent and written HIPAA authorization to publish this case report.

Report

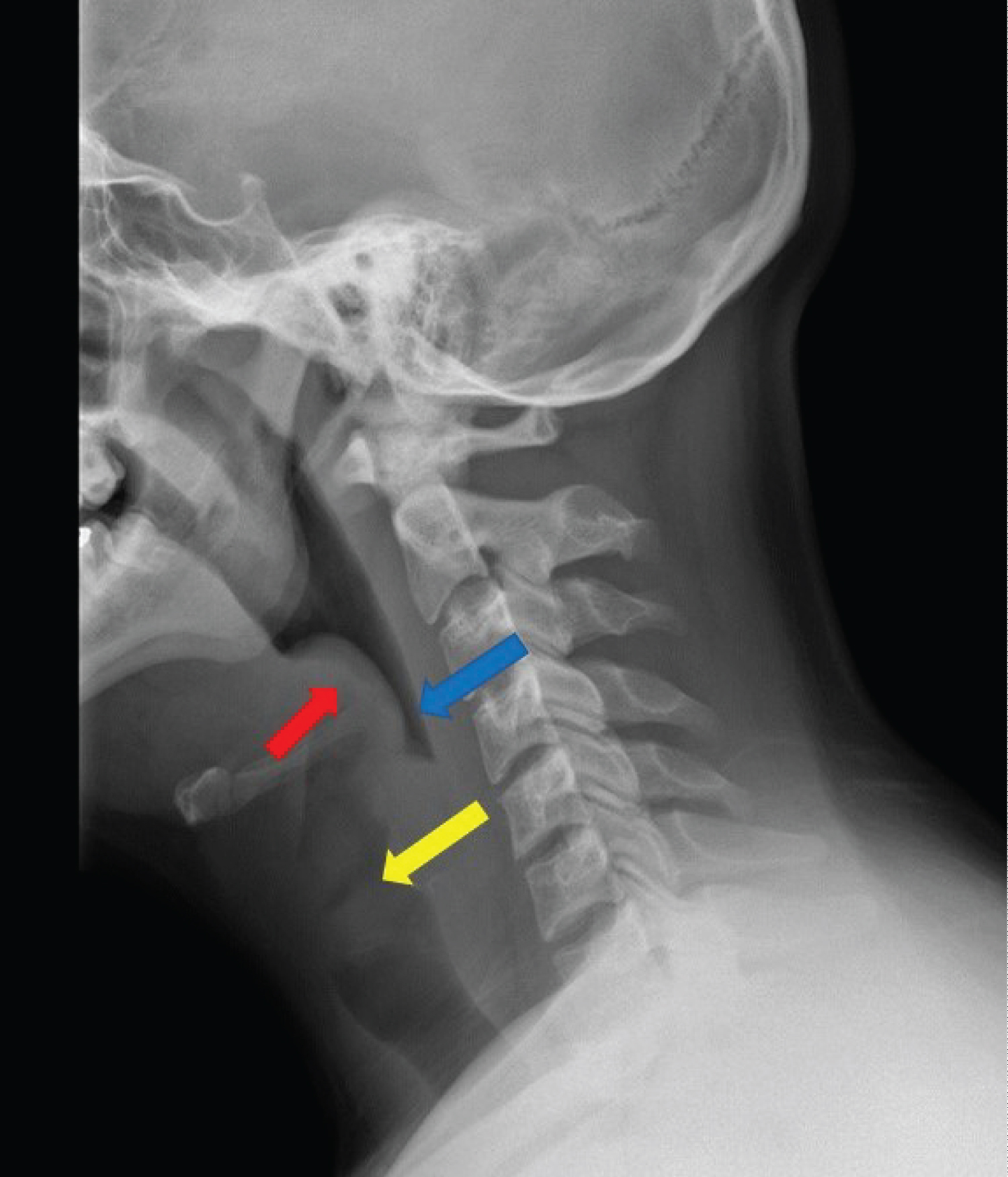

A 19-year-old man initially presented to the urgent care clinic with complaints of sore throat and laryngitis for three days. He was an otherwise healthy Hispanic man without prior comorbidities and a non-smoker; the patient was not vaccinated for COVID-19. There were no signs consistent with a bacterial process; he was requested to undergo COVID-19 testing and advised to take ibuprofen for pain. One week later, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with progressively worsening sore throat and dysphagia and was noted to have a positive COVID-19 test from one week prior. The patient also reported history of intermittent swelling of various body parts including his feet and testicles, but he denied any diagnosis of angioedema. In the ED, lateral X-ray of the neck revealed an enlarged epiglottis and narrowing of the hypopharynx consistent with possible epiglottitis (Figure 1). While in the ED, the patient also reported having dyspnea at rest and had to remain in an upright seated position in order to ensure airway patency. He was administered ceftriaxone (2 gm intravenous), racemic epinephrine (2.25%; 0.5 ml, inhaled nebulizer) and dexamethasone (10 mg intravenous) in the ED. Evaluation by the Head & Neck surgeon (HNS) revealed watery edema of the epiglottis which was visible in the oral cavity; there was no noted swelling or abnormalities of the lips, tongue, tonsils, uvula or orophanynx. Decision was made by the HNS to bring the patient to the operating room for direct laryngoscopy and any further procedures as indicated including but not limited to tracheostomy or abscess drainage.

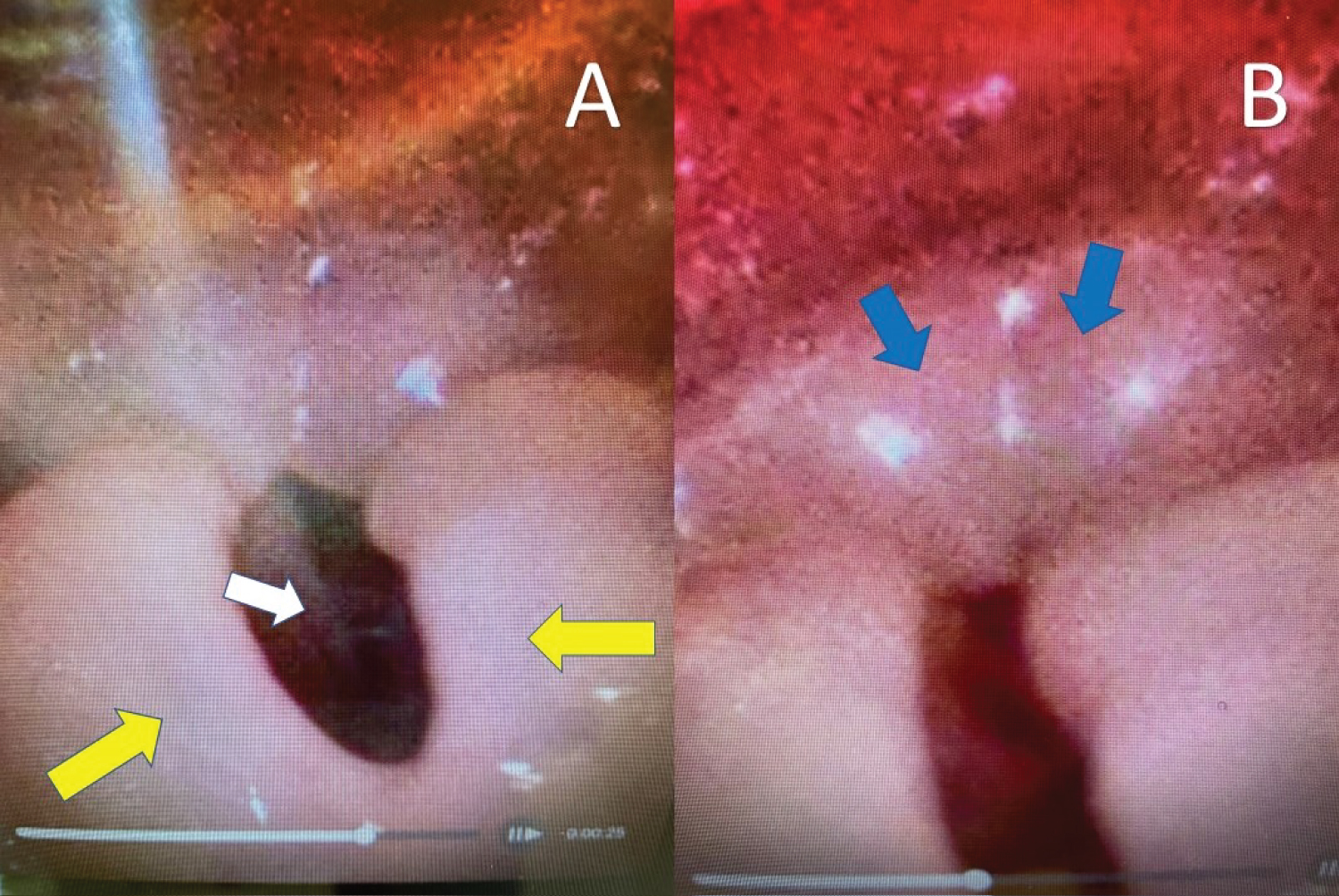

In the operating room, the surgeon sprayed the nose with neosynephrine and an AMBU (AMBU, Ballerup, Denmark) a Scope 4 rhinolaryngoscope slim was inserted into the left nasal cavity. Flexible laryngoscopy was performed trans-nasally, and the laryngeal structures were visualized. The nasal cavity, nasopharynx, and base of the tongue were visualized and appeared normal. The epiglottis, as well as the aryepiglottic folds and arytenoids, were edematous; the true vocal folds appeared normal and mobile. The supraglottic structures were swollen including the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and arytenoids (Figure 2). Therefore, the decision was made by theHNS surgeon and anesthesiologist to secure the airway via direct laryngoscopy or fiberoptic intubation. General anesthesia with rapid sequence induction was induced with propofol 150 mg intravenous iv, and succinylcholine 160 mg iv. Using the PRO-VUE (Flexicare, Irvine, California USA) video largyngoscope (Blade 3), three attempts were necessary in order to secure the airway due to supraglottic swelling, and size 6.0 endotracheal tube was able to be inserted.

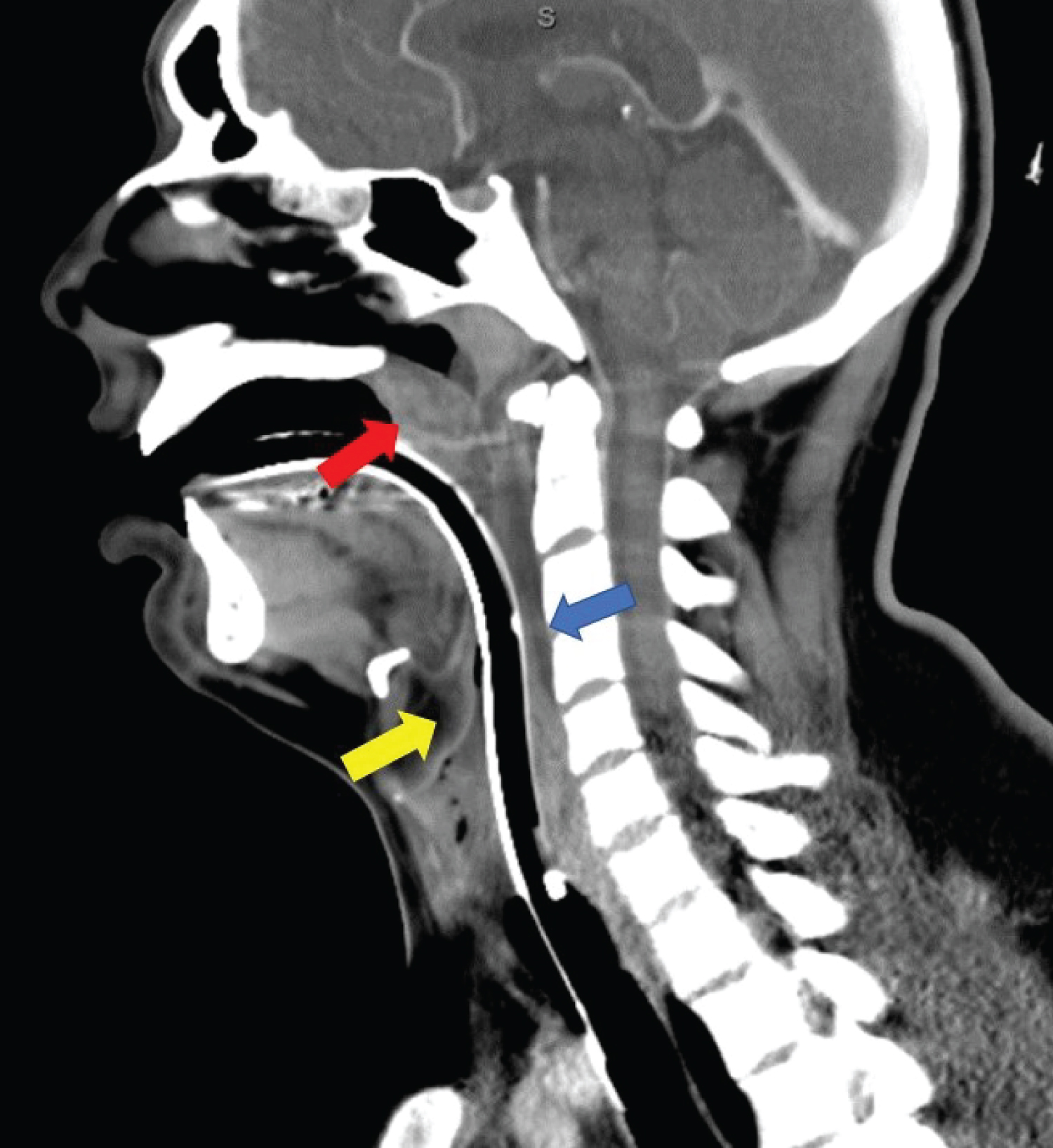

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and started on a short course of dexamethasone. While in the ICU with the patient intubated, computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck with intravenous contrast revealed oropharyngeal swelling (Figure 3); no abscesses were seen. In the ICU, ventilator settings were the following: Mode: Assist control (volume control +); Rate: 16 /min; tidal volume set (ml): 500 ml; FiO2 (%): 60 %; PEEP/CPAP/EPAP (cmH2O): 5 CM H2O. On post-op day 2, the HNS evaluated the patient and performed a bedside direct laryngoscopy with a Miller 2 blade and noted the epiglottis was normal; the patient was able to be successfully weaned and extubated.

During the admission, the patient was found to have a C1 esterase deficiency. The patient was discharged home on post-operative day 5 and was able to return to normal activities immediately upon discharge. At the time of discharge, the patient was prescribed Icantibant (bradykinin 2 inhibitor; 30 mg subcutaneous) and advised to use it only if any signs of angioedema (i.e., pharyngeal or extremity swelling) began to occur.

Discussion

Despite the decline of H. influenza B infections, acute epiglottitis remains a potentially life-threatening illness that requires urgent attention. Epiglottitis is a critical diagnosis and evaluation and care must be intentional and well planned. Our case report describes a 19-year-old male patient presenting to the ED with acute epiglottitis presumably due to COVID-19 infection.However, the patient had described a past history of angioedema notable for facial and mild extremity swelling.The patient had never been tested for C1 esterase deficiency and did not carry a diagnosis of Hereditary Acquired Angioedema at the time of ED admission.

Our case report demonstrates the ever-increasing complexity in accurately diagnosing the etiology of epiglottitis in the age of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, COVID-19 associated epiglottitis has been reported [5-10], and hereditary (or acquired) angioedema due to C1 esterase deficiency has also been shown to be associated with laryngeal edema and upper airway obstruction [13,14]. However, the two diagnoses have never been reported together in a single patient. This case stands dramatically distinct to other reported cases of COVID-19 associated epiglottitis combined with a presumptive diagnosis of HAE. Due to this patient’s past history of clinical angioedema, it was difficult to ascertain if the epiglottis swelling was a result of COVID-19 infection alone or due to his history of acquired angioedema or together creating a synergistic clinical scenario that potentially exacerbated the signs and symptoms associated with epiglottitis. Therefore, thorough history taking is critical in establishing a differential diagnosis and ensuing treatment.

Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency is a rare disease with an estimated frequency of 1 in 50,000 in the general population without major racial or gender differences. HAE is clinically manifested by recurrent episodes of localized subcutaneous or submucosal edema lasting for 2-5days. Almost all cases of HAE are caused by mutations in the SERPING1 gene resulting in a deficiency in functional plasma C1 esterase inhibitor (C1EI), a serine protease inhibitor that normally inhibits proteases in the contact, complement, and fibrinolytic systems. Current treatment of HAE includes long-term prophylaxis with attenuated androgens or human plasma-derived C1EI and management of acute attacks with human plasma-derived or recombinant C1EI, bradykinin, and kallikrein inhibitors, each of which requires repeated administration.

COVID-19 may invade the respiratory tract by binding to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on the respiratory epithelium via glycoprotein spikes. ACE is responsible for degrading bradykinin-- the peptide thought to cause angioedema. Although our patient was not on ACE2 inhibitors, these medications in susceptible individuals may cause angioedema of the face and larynx, leading to respiratory compromise, not unlike epiglottitis. COVID-19 viral glycoproteins bind to ACE2 receptors in the airway, causing downregulation of the ACE protein, leading to angioedema through the same mechanism.

Epiglottic swelling is a potentially life-threatening medical emergency, and patients can quickly progress to respiratory distress even if they appear stable. The decision whether or not to intervene in the ED and proceed directly to the operating room is a critical decision-making process. In our case, the decision to bring the patient to the operating room was made based on the patient’s symptoms of dyspnea at rest and dysphagia, as well as results of lateral X-ray of the neck revealing enlarged epiglottis and narrowing of the hypopharynx. Even accidental manipulation of the airway via flexible laryngoscopy could exacerbate swelling and lead to respiratory distress and/or loss of the airway. The surgeon must evaluate the airway and decide if intubation is possible or if a surgical airway (i.e., tracheostomy) needs to be established. In our case, the patient's epiglottis was visibly swollen in the oral cavity. Therefore, the decision was made to transfer the patient to the OR quickly and prepare for intubation with surgical airway as a back-up plan. The anesthesiologist and surgeon should work closely together and establish a plan to secure the airway. During intubation, manipulation of the epiglottis and any other swollen laryngeal structures should be minimized. The most senior anesthesiologist or surgeon should perform the intubation as only one attempt may be possible. Topical anesthetics should also be avoided to minimize sudden loss of the airway. If intubation is not deemed safe, then an awake surgical tracheostomy is indicated. The neck should be injected with local anesthetics and a tracheostomy is performed with minimal sedation. If the airway is lost, and the patient cannot be ventilated then a slash tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy should immediately be performed. Use of video laryngoscopic equipment are key adjuncts to successfully securing the patient’s airway.

Due to the presence of COVID-19 in this patient, infectious disease precautions were implemented. The use of a powered air-purifying respirator is indicated, especially given the context of aerosolizing risks and/or emergent conversion to a surgical tracheostomy. A negative pressure room in the OR and ICU is also considered indicated if possible.

Given the tremendous impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health of patients worldwide, as well as the ever-increasing endemic nature of COVID-19, physicians should maintain clinical suspicion for acute epiglottitis in COVID-infected patients presenting with airway distress. Most importantly, a complete differential diagnosis for the etiology of acute epiglottitis should be considered in to order to facilitate diagnosis and optimal management strategies. For our patient, long-term management measures were implemented for possible future episodes of hereditary acquired angioedema.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of Interests/Financial Disclosures

None.

References

- Feigin RD, Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison GJ, et al. (2009) Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Baiu I, Melendez E (2019) Epiglottitis. JAMA 321: 1946.

- Mathoera RB, Wever PC, Van Dorsten FRC, et al. (2008) Epiglottitis in the adult patient. Neth J Med 66: 373-377.

- Ozaki M, Murashima K (2019) Use of a tracheal tube as a nasally inserted supraglottic airway in a case of near-fatal airway obstruction caused by epiglottitis. Case Rep Anesthesiol 2019: 2160924.

- Smith C, Mobarakai O, Sahra S, et al. (2021) Case report: Epiglottitis in the setting of COVID-19. IDCases 24: e01116.

- Iwamoto S, Sato MP, Hoshi Y, et al. (2021) COVID-19 presenting as acute epiglottitis: A case report and literature review. Auris Nasus Larynx.

- Renner A, Lamminmäki S, Ilmarinen T, et al. (2021) Acute epiglottitis after COVID‐19 infection. Clin Case Rep 9: e04419.

- Fondaw A, Arshad M, Batool S, et al. (2020) COVID-19 infection presenting with acute epiglottitis. J Surg Case Rep 2020: 280.

- Cordial P, Le T, Neuenschwander J (2022) Acute epiglottitis in a COVID-19 positive patient. Am J Emerg Med 51: 427.

- Emberey J, Velala SS, Marshall B, et al. (2021) Acute epiglottitis due to COVID-19 infection. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med 8: 002280.

- CDC (2022) Symptoms of COVID-19.

- Johns Hopkins University & Medicine (2022) COVID-19 dashboard. Coronavirus Resource Center.

- O'Bier A, Muñiz AE, Foster RL (2005) Hereditary angioedema presenting as epiglottitis. Pediatr Emerg Care 21: 27-30.

- Bork K, Hardt J, Schicketanz K-H, et al. (2003) Clinical studies of sudden upper airway obstruction in patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency. Arch Inten Med 163: 1229-1235.

Corresponding Author

Antonio Hernandez Conte, MD, MBA, Department of Anesthesiology, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, 4867 Sunset Blvd., 1st Floor, Los Angeles, California 90027, Tel: (323)-573-3900, Fax: (323)-783-8722

Copyright

© 2022 Chowdhuri S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.