Anesthesia in A Patient With an Internal Carotid Artery Aneurysm Presenting as Massive Recurrent Projectile Epistaxis: A Case Report

Abstract

Severe projectile epistaxis due to non-traumatic internal carotid artery aneurysms is potentially life threatening but extremely rare, with hardly any report existing in the literature. We present the case of a 21-year old male with a history of recurrent torrential epistaxis associated with headache and dizziness. Catheter angiography revealed two aneurysmal dilatations at the cavernous and supraclinoid segments of the right internal carotid artery. The initial treatment with a common carotid artery occlusion by the use of a Poppen clamp and subsequent ligation performed on an elective basis failed due to recanalization and collateral circulation. After massive rebleeding, the patient underwent an emergency ligation of common carotid artery; and subsequent craniotomy, and clipping of the ophthalmic segment of the right internal carotid artery. Epistaxis and headache resolved after the surgery with the patient discharged five days postoperatively. Awareness and understanding of important considerations including control of epistaxis, prevention of aspiration during induction, maintenance of hemodynamic stability, prevention of vasospasm and a rapid return to a conscious state to allow for early neurologic evaluation are thus crucial in formulating the appropriate anesthetic management plan for this patient.

Keywords

Cerebral aneurysm, Epistaxis, Internal carotid artery

Introduction

Nontraumatic cavernous internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysms are a rare cause of epistaxis, with most usually presenting with signs and symptoms of a space-occupying lesion. Although exceedingly rare, recurrent epistaxis resulting from such aneurysms may potentially be fatal [1,2]. We report the anesthetic management of a patient with a nontraumatic cavernous ICA aneurysm causing massive recurrent projectile epistaxis who underwent multiple surgeries.

Case Summary

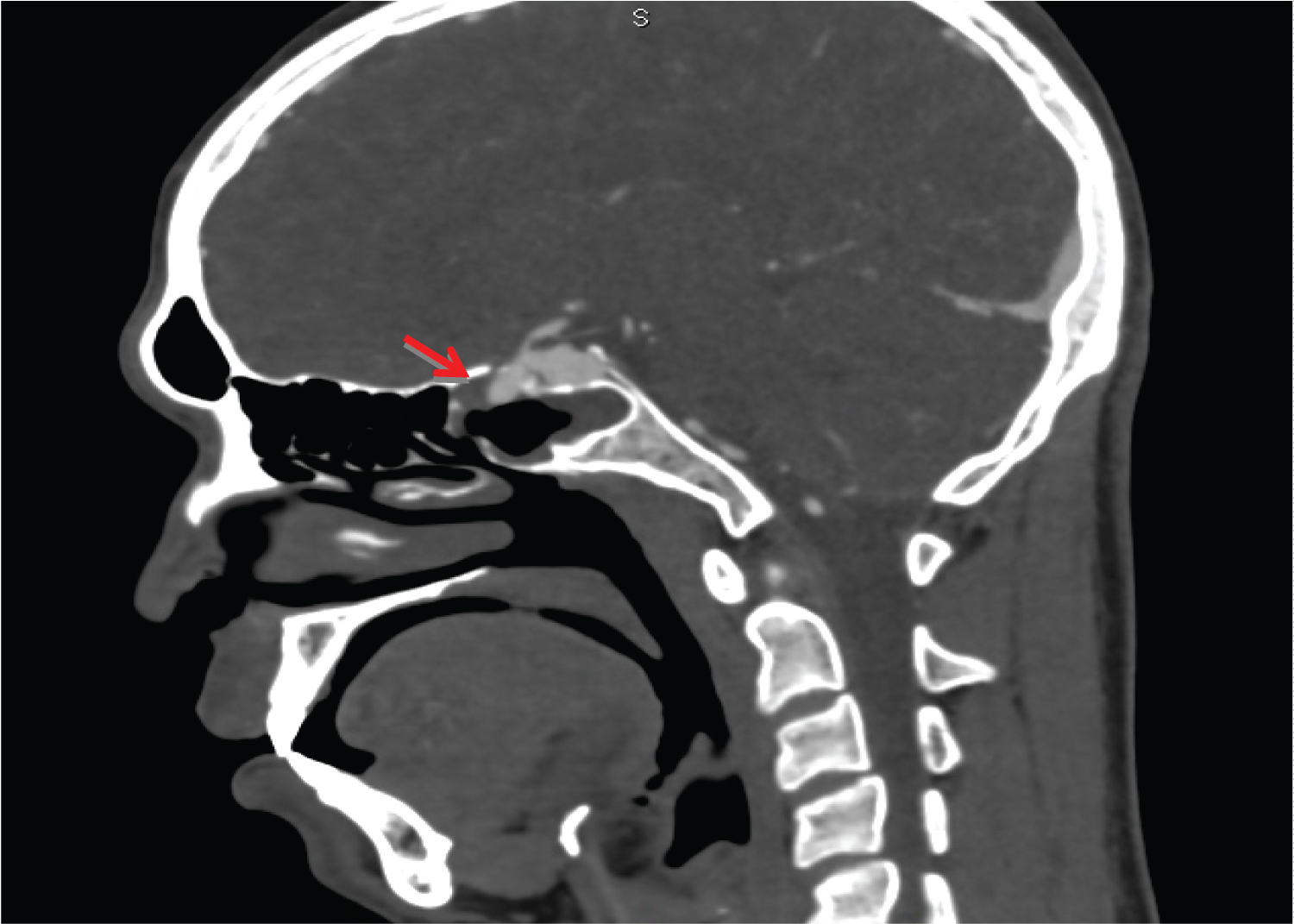

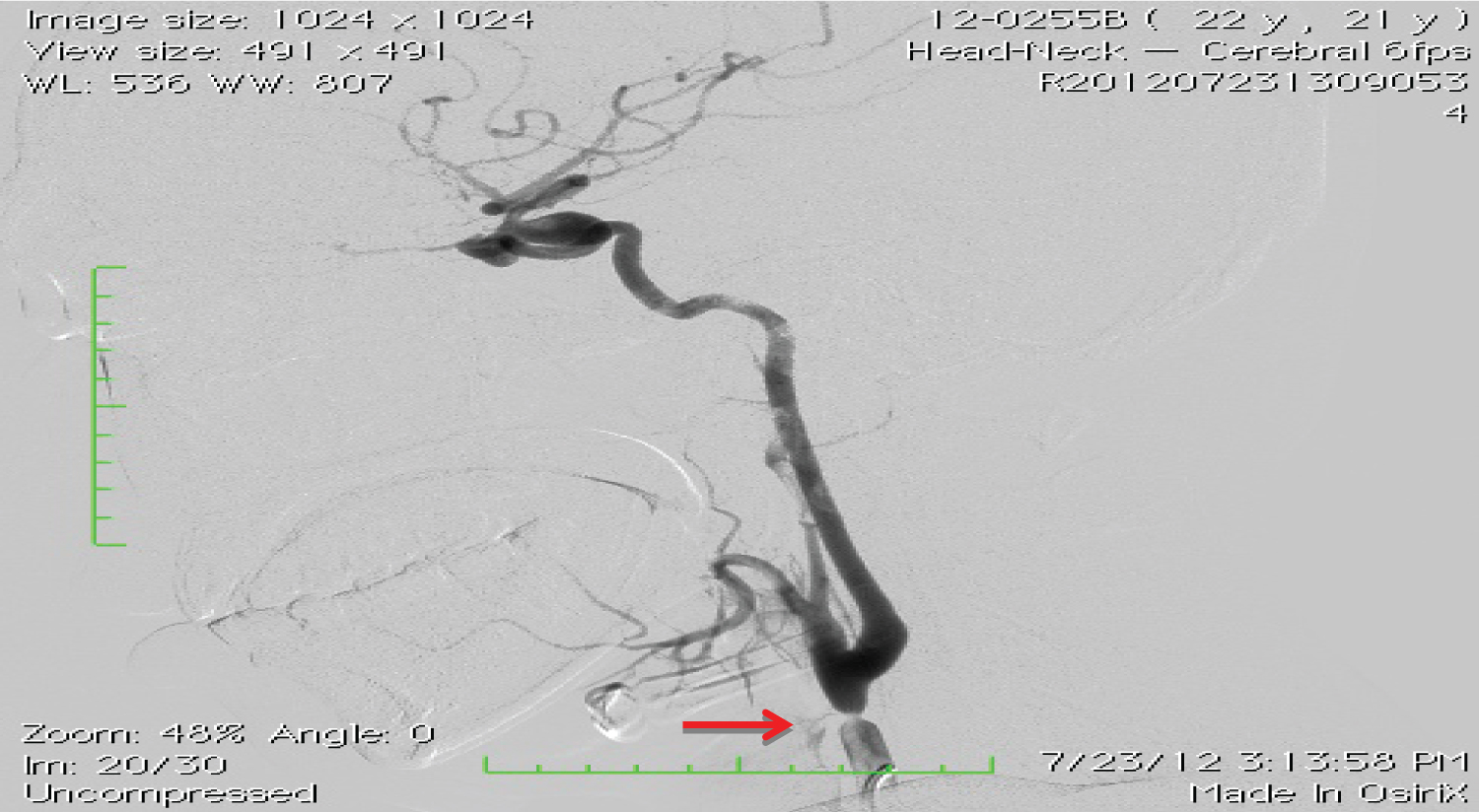

A 21-year old previously healthy male was initially seen with recurrent episodes of epistaxis over a three-month period that either resolved spontaneously or was adequately controlled by anterior nasal packing (Figure 1). These were associated with headache and dizziness, with the patient denying any visual complaints or any history of major head trauma. A complete neurologic and otorhinolaryngologic examination did not reveal any abnormalities. CT and catheter angiography revealed two aneurysmal dilatations - the larger situated at the junction of the distal cavernous segment and proximal supraclinoid segment of the right ICA measuring 1.3 × 1.1 × 1.3 cm and a smaller aneurysm in the distal cavernous segment measuring 0.8 × 0.6 × 0.9 cm telescoping into the right sphenoid sinus (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Endovascular treatment with placement of stent and coil embolization was offered to the patient. However due to financial constraints, the patient only consented to right carotid Poppen clamp application and subsequent common carotid artery ligation and Poppen clamp removal five days later. The patient was discharged a week postoperatively with no new episodes of epistaxis or neurologic deficits.

However four months after the initial surgery, a recurrence of the projectile epistaxis prompted an emergency admission where a repeat angiogram demonstrated the two aneurysms and short segment stenosis in the distal right common carotid segment possibly due to recanalization (Figure 4). The surgical plan was for possible reapplication of the Poppen clamp and right carotid ligation. However, massive rebleeding amounting to approximately two liters prompted an emergency right common carotid artery ligation under general anesthesia. The epistaxis was initially controlled with anterior nasal packing and the airway was secured through rapid sequence induction. Provisions were made to maintain the patient's systolic blood pressure within baseline values during carotid ligation. He was discharged four days after the procedure without new neurologic complaints.

On admission the following month for a scheduled follow-up angiogram, the patient again had an episode of non-projectile epistaxis amounting to one liter. Catheter angiography demonstrated a trickle of flow into the right ICA (Figure 5). The patient subsequently underwent craniotomy and clipping of the ophthalmic segment of the right ICA under general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, the patient's blood pressure was reduced to about 20% of baseline values and prophylaxis for the normal hypertensive response to painful stimuli was instituted. Post-application of the clip, intravenous phenylephrine was administered, with a systolic blood pressure parameter of 140 to 160 mmHg, to enhance collateral cerebral circulation. The patient was neurologically intact after surgery and transferred to the intensive care unit, with provisions for administration of norepinephrine instituted to maintain the target SBP during the first 24 hours postoperatively. After being observed in the ICU and ward for 10 days, he was discharged. He has had no further episodes of epistaxis since and is neurologically normal. A routine follow-up angiogram performed four months after the surgery revealed no evidence of aneurysm filling or right common carotid recanalization (Figure 6).

Discussion

Cavernous carotid aneurysms make up less than 2% of all intracranial aneurysms and are subdivided into traumatic and nontraumatic types. Traumatic aneurysms are diagnosed early due to a history of trauma typically associated with basal skull fractures and a rapid progression of symptoms, with epistaxis developing in seven weeks on average. On the other hand, nontraumatic aneurysms presenting with epistaxis are unusual and exceedingly rare. The recurrent presentation of epistaxis may be due to a hematoma that tamponades a small rupture in the sphenoid sinus [3].

Several treatment options have been advocated for such carotid aneurysms ranging from no treatment with close observation to surgery [4]. Surgical interventions including endovascular treatment should be seriously considered in patients presenting with neurological symptoms, evidence of radiographic enlargement, subarachnoid hemorrhage or epistaxis. Endovascular therapies, either through primary embolization or endovascular occlusion, may be the best treatment for ruptured and unruptured aneurysms immediately after a diagnostic angiography [5]. However these endovascular techniques are expensive and remain prohibitive for some patients in countries like the Philippines. Open surgical techniques consisting of proximal ligation of the common carotid artery in the neck or clipping of the aneurysm neck are thus still performed [6].

Patients with internal carotid aneurysms causing profuse epistaxis for surgery require several important considerations in anesthetic management. Initial management includes adequate control of the torrential epistaxis through either anterior nasal packing using ribbon gauze with petroleum jelly or manual compression of the involved carotid artery at the cervical area. The use of urinary balloon catheters is recommended to produce transient hemostasis if the epistaxis remains largely uncontrolled, however this may require the assistance of an otorhinolaryngologist. Ultimately, surgical occlusion is the final treatment option to permanently control possibly life-threatening nasal bleeding [5]. Volume resuscitation and placement of standard monitors including direct intra-arterial blood pressure measurement should also be instituted prior to induction of anesthesia and tracheal intubation.

Rapid sequence induction in cases of a compromised airway from hemorrhage is most prudent with rocuronium (1.0 to 1.2 mg/kg) to minimize the period that the patient's airway is unprotected from aspiration while maintaining cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) and preventing aneurysm rupture. The patient's blood pressure during induction, laryngoscopy and intubation should be closely monitored and maintained approximately within 20% below the baseline value through conscientious use of anesthetic agents and adjuncts such as fentanyl, propofol, β-adrenergic antagonists, intravenous lidocaine or inhalation anesthetics.

Balanced anesthesia with both intravenous and inhalation anesthetic can be used to reduce transmural pressure (TMP) during dissection and clip application. This also ensures the avoidance of cerebral ischemia, dangerous increases in blood pressure and wide fluctuations in the CPP. The anesthetic management can likewise be tailored to allow early awakening and prompt neurologic assessment postoperatively at all stages of surgical management.

Although partial occlusion by a Poppen clamp and cervical carotid ligation is a viable and reasonable treatment option for a selective group of internal carotid artery aneurysms, it is not without danger. The interruption of the pulsatile flow to an aneurysm through these techniques carries the risk of causing ischemia of the ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere and ascending thrombus formation [7]. Close monitoring of all vital parameters in the ICU with adequate hydration with colloids to keep the blood pressure approximately 10% higher than preoperative levels is important [6].

Similarly, provisions for administration of intravenous norepinephrine or phenylephrine should also be instituted post clipping to maintain a systolic blood pressure 20% above baseline values. This rise in mean blood pressure aims to enhance collateral cerebral circulation that may prove beneficial in the prevention of neurologic deficits due to cerebral vasospasm.

Conclusion

Rare cases of massive epistaxis secondary to cavernous carotid aneurysms may be safely treated through open surgery provided an individualized anesthetic management plan has been formulated. This requires a thorough understanding of the patient's current physiologic state as well as the neurologic and hemodynamic goals for each specific surgical procedure. Ultimately, a multidisciplinary approach involving the neurosurgeon, radiologist, otorhinolaryngologist and anesthesiologists is crucial in developing a treatment plan resulting in successful outcomes.

References

- Karkanevatos A, Karkos PD, Karagama YG, et al. (2005) Massive recurrent epistaxis from non-traumatic bilateral intracavernous carotid artery aneurysms. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 262: 546-549.

- Moro Y, Kojima H, Yashiro T, et al. (2003) A case of internal carotid artery aneurysm diagnosed on basis of massive nosebleed. Auris Nasus Larynx 30: 97-102.

- Chaboki H, Patel AB, Freifeld S, et al. (2004) Cavernous carotid aneurysm presenting with epistaxis. Head Neck 26: 741-746.

- Lehmann P, Saliou G, Page C, et al. (2009) Epistaxis revealing the rupture of a carotid aneurysm of the cavernous sinus extending into the sphenoid: Treatment using an uncovered stent and coils. Review of literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 266: 767-772.

- Nomura M, Shima H, Sugihara T, et al. (2010) Massive epistaxis from a thrombosed intracavernous internal carotid artery aneurysm 2 years after the initial diagnosis--case report. Neurol Med Chir 50: 127-131.

- Rathore YS, Chandra PS, Kumar R, et al. (2012) Monitored gradual occlusion of the internal carotid artery followed by ligation for giant internal carotid artery aneurysms. Neurol India 60: 174-179.

- Jain KK (1963) Partial carotid occlusion as treatment for intracranial internal carotid aneurysms. Can Med Assoc J 88: 247-251.

Corresponding Author

Karl Matthew C Sy Su MD, Department of Anesthesiology, Philippine General Hospital, University of the Philippines Manila, Philippines

Copyright

© 2021 Sy SU KMC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.