Missed Nursing Care in a Second-Level Surgical Care Area in Northern Italy: A Descriptive Qualitative Study

Abstract

Introduction: The phenomenon of omitted or delayed nursing care, also known as Missed Nursing Care (MNC), is a nursing issue, affecting all over the world and have been subject of multiple studies in Italy as well.

The evidence to date summarized, comes mainly from research designs that consider the perceptions of nursing staff but the area of patient’s experience, remains little investigated.

Aim : The study analyzed the MNC phenomenon according to the experience of caring for some patients admitted to the surgical area in a surgical department of a second-level hospital in northern Italy in order to determine which elements of nursing care might be delayed or omitted.

Methods : A descriptive qualitative study design was used through Shilling's [1] conceptual model with thematic analysis, using semi-structured interviews for patients who were previously admitted to the surgical areas of the identified hospital.

The research adhered to the checklist and guidelines COREQ.

Results: From the analysis of the interviews, it was found that the MNCs perceived most frequently by the patients, in the settings considered in this study, were the failure of the staff to introduce themselves to the users during intake, upon the arrival to the unit and also to the inpatient rooms, the lack of explanation of the care activities that would take place during the shift, the absence of performing or proposing oral care and to sanitize hands of the inpatients. From what the respondents said, the other care activities, were found to be delivered satisfactorily and without delays finding no further shortcomings.

Conclusions : The results of this study helped to identify, through patients' perceptions, some elements of care that are omitted or delayed, but which results to be essential in care practices.

Knowledge of patients' perceptions of MNCs helps to identify variables that characterize the quality of care, enabling professionals and policy makers to improve actions on care processes.

Keyword

Missed nursing care, Surgical area, Nursing care, Qualitative study

Introduction

A patient's perception of hospitalization is experienced in a very personal way in a context in which he is vulnerable. The study of human well-being is undoubtedly a complex issue on which social scientists have not reached consensus. The lack of agreement on its conceptual delimitation is due, among other things, to the complexity of the problem, mainly determined by its temporary nature, the competition of multiple factors, objective and subjective.

The patient during hospitalization interfaces mainly with the nursing staff, consequently, will expect that his well-being will be ensured by the this staff and that they will strive to know the feelings and his expectations of their patients so that they can plan the best interventions that can meet their needs [2].

Nurses, are engaged in many activities and often have a considerable number of patients in their charge, so sometimes situations of missed or delayed care delivery can occur.

As described by Sist and colleagues [3] and as analyzed and detailed in some scientific works by Kalish and colleagues [4,5], this phenomenon, is transversely present in many Western countries and is internationally known under the term Missed Nursing Care (MNC).

On the phenomenon of MNCs, several works emerge in the literature such as that of Kalish [6] and Palese and colleagues [7], who report the relationship between mortality and qualitative/quantitative staff composition, infection rate, occurrence and management of pressure injuries, patient falls, hospital length of stay, adverse events, post-surgical complications, and perceived user satisfaction.

Other publications, have shown that the phenomenon of MNCs, would seem to be more present in units in the medical-surgical area, as opposed to intensive care and maternal and childcare [8,9].

Over the past few years, other authors, have highlighted additional areas of lost care, focusing on communication and relational aspects such as comforting and communicating with patients, health education to patients and their families.

Difficulties were also emerging in the post-surgical care phase as indicated by a qualitative study by See and colleagues [10].

In Italy, many of important experiences diffused, highlighted the importance of the value of nursing practices, noted the presence of non-assistance activities that take time away from professionals, emphasized the need to implement educational pathways with a view to the appropriate attribution of care interventions to support staff, and to project nursing practices toward evidence-based medicine [11] .

In an experience in Italian oncohematology settings, some difficulties emerged in the aspects of personalization of care, communication, education, and patient information even in the discharge planning phase [12].

In an important research work in the medical, surgical and mixed areas, compiled by Bagnasco and colleagues [13], it was found that the most omitted activities, turned out to be oral hygiene, education towards the patient and his family, comfort and communication to the caregiver while the least omitted practice, figured to be pain management.

In this analysis, in which 3,666 nurses located in 40 Italian hospitals participated, no major differences were found between care settings, and it was found that MNCs occurred mainly in the morning shift.

Aim

The generative question of the present work aimed to understand through the experiences told by some patients, whether the phenomenon of missed nursing care occurs in surgical areas of the hospital considered under study, and if it turns out to be present, for which nursing activities and in which extension, The results that will emerge, may be useful to nurses and decision makers, to implement possible strategies for improvement.

Methods

The study setting was represented by a surgical department in northern Italy where there was already an analysis of missed care.

The inpatient areas considered were areas where no SARS Covid 2 virus-positive patients were admitted. The study was developed through a qualitative descriptive research design using the conceptual and thematic analysis model according to Shilling [1].

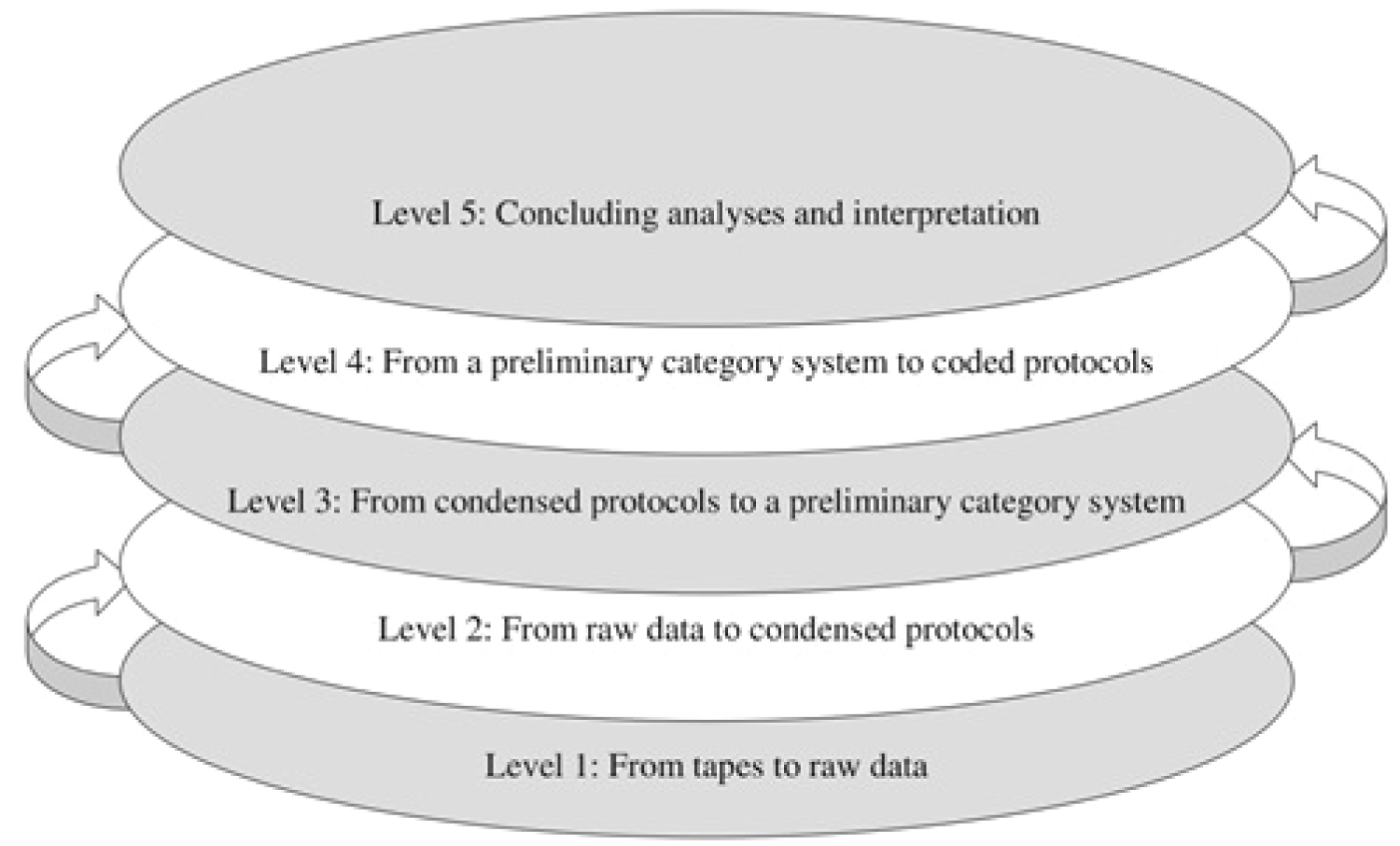

This method aims to develop thematic content analysis as a systematic and rule-based process of analyzing verbal and textual data such as interviews, group discussions, and documents (Figure 1).

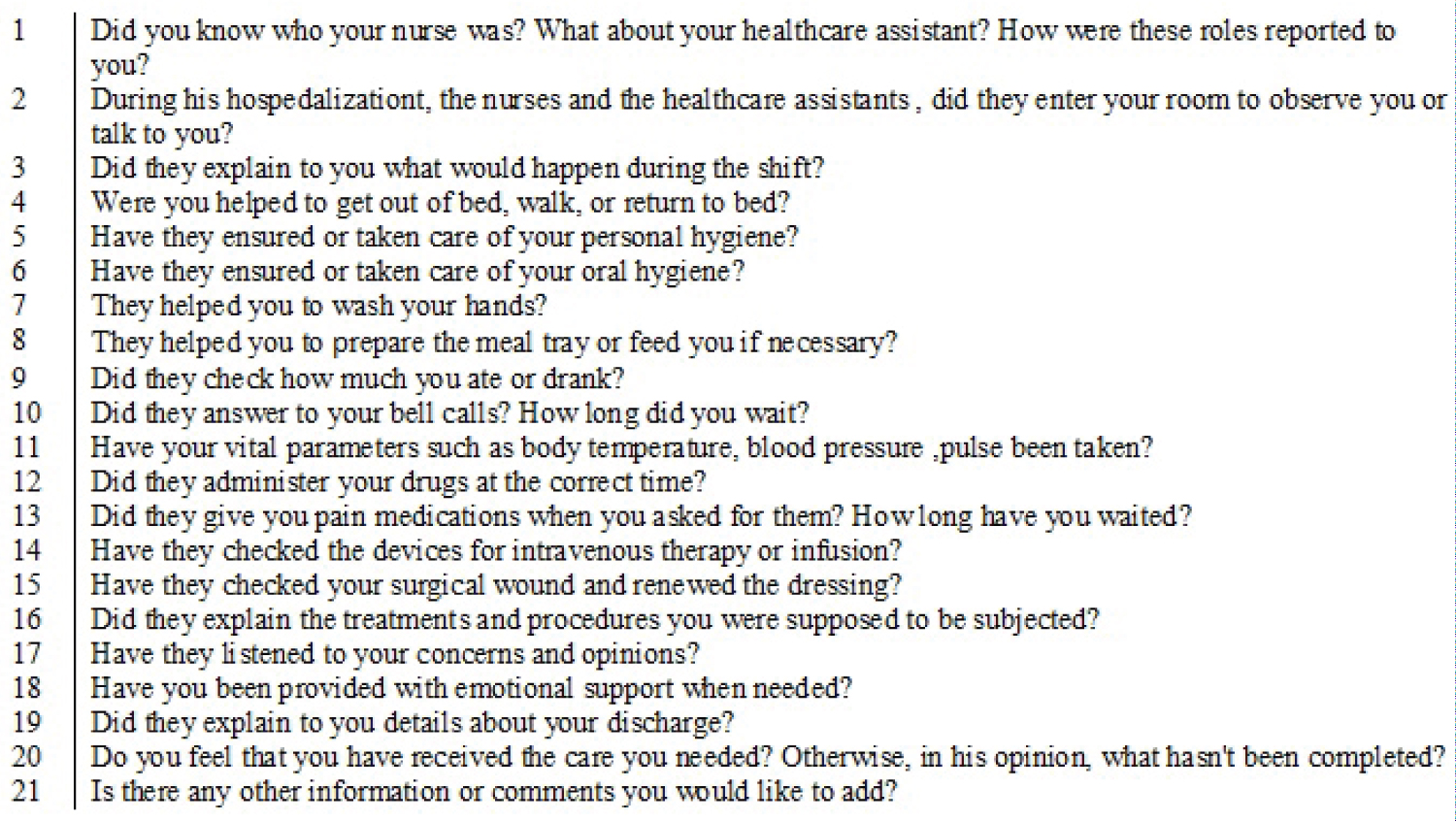

Steps include verbatim transcription of interviews into raw data, condensation and structuring of data, creation and application of a category system, and visualization of data and results for conclusive analysis and interpretation. A set of questions was composed to be proposed to participants through semi-structured interviews that lasted approximately 30 minutes.

The proposed items (Figure 2) were derived from previous study work conducted by Monsivais and colleagues [14].

The study period extended between November 2021 and August 2022 with purposeful convenience sampling by identifying "key informers”, including subjects of legal age, who were admitted to certain areas of the surgical department hospitalized not less than 4 days, while people unable to cooperate or with clinically diagnosed cognitive-perceptual deficits, subjects of minor age and those who refused to participate were excluded from the research.

At first, five sample units were estimated and engaged but from the iterative contextual content analyses, additional themes emerged to be explored therefore, six more respondents were interviewed for a total of eleven people allowing data saturation to be reached.

The participants’ testimonials were written down with verbatim transcription and were then examined by defining response codes that generate thematic categories and subcategories and then arrived at the definition of a core category.

Regarding data transcription, each respondent, was identified with the letter "R" and a randomly assigned number. After the initial coding, through a second level of data abstraction [15], the researchers (GD and CT), started a clustering process [16], identifying codes, subcategories and core categories.

To pursue the quality criteria of the study, the paper was submitted to the guidelines indicating the reporting of qualitative research: Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research” (COREQ) [17] (Appendix 1).

Regarding the socio-demographic analysis of the participants: The majority were male, the age group most represented was 61 to 70-years-old, with secondary school certificate .

Ethical Considerations

Before administering the interview, participants had an information sheet where there was a brief presentation of the project and where it was best explained how their data and answers would be used, ensuring full privacy.

The measures taken by the regulations on privacy and processing of personal data indicated by Legislative Decree No. 196 of 2003.

Participants voluntarily joined the study with the possibility of discontinuing participation at any time.

It was stated that the interviews would be recorded to have the possibility to access the collected data again and to allow transcription. It was assured that the recordings would be deleted after they were no longer useful for research purposes, the data would not be given to third parties and would remain available for a duration of seven years.

Interviews were conducted in ambulatory areas dedicated to follow-ups after hospitalization to which participants were invited to present. They were conducted in environments where the criteria of privacy and respect for the content of the information exchanged in the full protection of the respondents were ensured.

Results

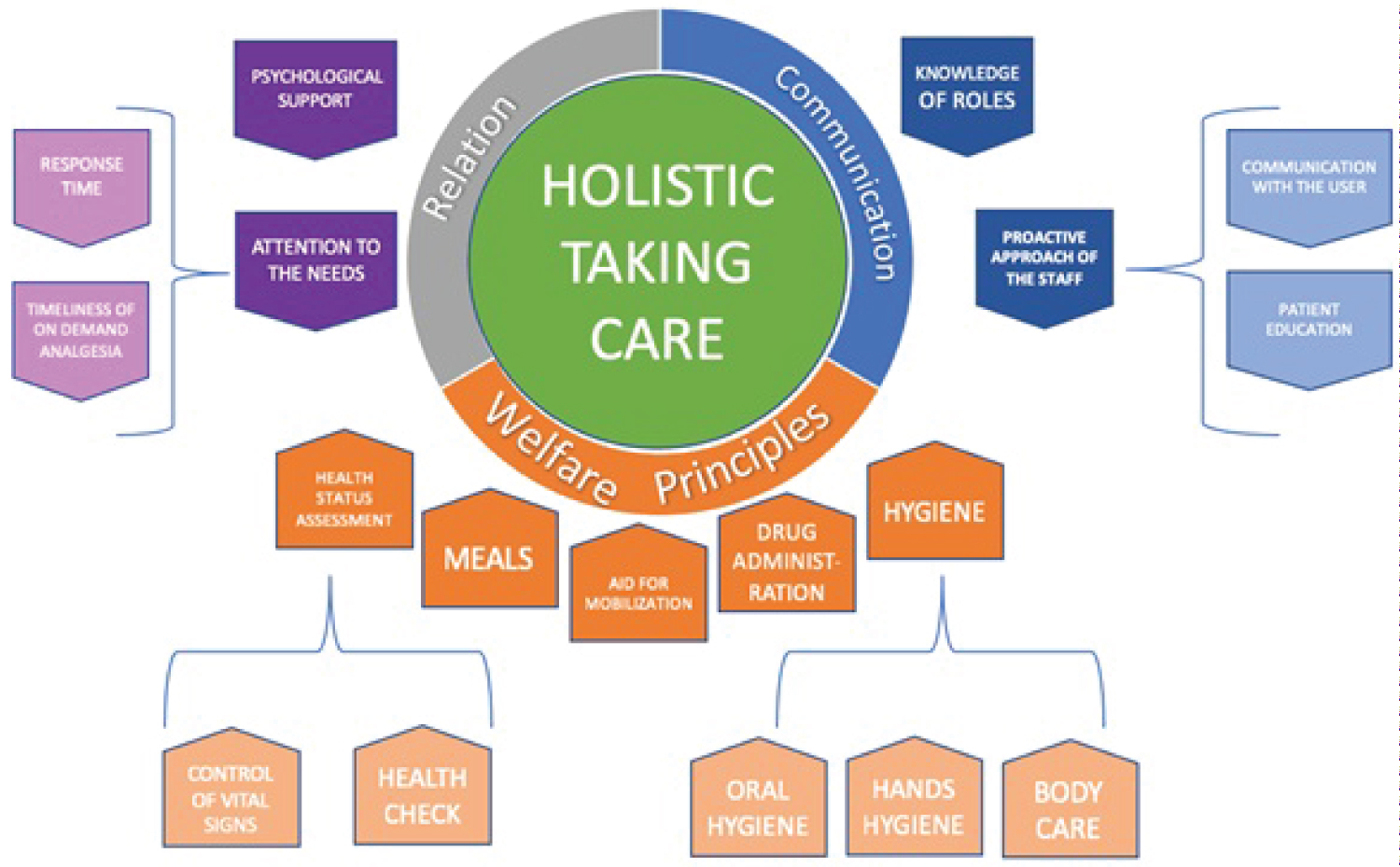

After collection and immersion in the data, several categories were identified, which enclosed other subcategories generated by codes that enabled the development of a conceptual map of the phenomenon under study. Three categories and nine subcategories fractioned into 13 codes, emerged (Figure 3).

The core category that emerged, was called "holistic care process" which expressed the main categories named: Communication, relationship, primary care.

The first category, named "communication" includes the subcategories "role knowledge, proactive staff approach" according with the codes called "user communication and patient education."

Patients were asked if at the beginning of their hospital stay the ward staff introduced themselves, manifesting their roles but, from the interviews, it was found that some respondents do not remember the presentation by the staff but that they learned to recognize the various figures in the following days during their hospital stay: <<I don't remember they introduced themselves. Only when I rang the bell and an auxiliary came, if it was the nurse's responsibility, she would tell me 'I'll call the nurse’>> (R3); <<I understood but was not told>> (R7).

Regarding the proactive approach by staff, those surveyed were asked if the staff came in the room for supervision or to had a conversation with inpatients, in this case, some stated that staff entered the room only after being called by bell : <<they entered the room only when I called them>> (R1), while others stated that nurses and support workers, were present even without requests from patients: <<yes, they entered often>> (R 11).

Instead, shortcomings were found on the explanation of the activities that would happen during the shift: <<I knew what was to be done during the day, the various IVs, schedules, meals, therapy. They did not tell me but I learned to understand it>> (R3); <<no, they did not communicate it to me>>(R2); <<sometimes>> (R6).

On the aspect of health education, no respondent expressed critical elements being they, surgical wound carriers, all patients said they were educated about the management of that at home: <<a nurse one day told me to watch his every step, so that at home I could do it myself>> (R4).

The second category called "Relationship" is supplied by the subcategories "attention to necessities, psychological support" with the codes "time of response, timeliness for treatment as needed."

Those surveyed, stated that the nursing staff asked every day if they needed anything.

Overall, the patients interviewed perceived that the nursing staff made sure that the inpatients did not have anxieties and fears related to the surgery, or more generally all the peculiarities of hospitalization.

<< I used to ask ...when are you remove my bladder catheter out? and they would reassure me by saying ... soon we will take it out...,same for the nasal feeding tube ...I used to ask will you remove it out? and at the appropriate time they took it out. Yes, they listened to me>>(R1); <<I was very frightened, but they explained to me what the surgery consisted of and they immediately calmed me down>>(R5).

The interview participants were asked if they needed pain medication after surgery and whether their requests were satisfied, and it was found that this aspect of nursing care was not omitted or delayed: <<I was asked if I was in pain and if I wanted any pain meds>> (R1); <<Yes I asked for pain medication and they gave to me immediately>>(R3); <<Yes I asked for several times and when they could they always gave them to me>>(R4).

The last category identified, was defined as "principles of care process" with the subcategories "mobilization, hygiene, meal, medication administration, health assessment," which in turn were supported by the codes "hand hygiene, oral hygiene, body care, nutrition assistance, nutrition/hydration control, medication administration as needed, infusion device control, vital parameters, surgical wound dressing."

No patient ever complained about mobilization; they all said they were helped in the first moments after surgery, getting out of bed or in assist them to go to the toilets, they were all strongly satisfied.

Regarding the subcategory "hygiene," it was divided into 3 different codes: hand washing, oral hygiene, and body hygiene.

No patients reported that they were not helped with body care, and some of them after the first 72 hours post-surgery stated that they were able to provide for themselves, while in the days immediately following surgery they needed help from the staff, and from what stated, this aspect was never neglected.

Asking about the help of handwashing, some patients said that it was never offered to them during their hospitalization: <<They never proposed me>>(R3); <<I had sanitizer on my bedside table but it was not offered to me>> (R7); <<I did it myself>> (R9).

In conclusion, regarding oral hygiene, some patients, report that it was not offered to them: <<No, honestly never>>(R3); <<no, never>>(R4); <<yes, they gave me mouthwash>> (R6).

Some patients were unable to recognize if the staff was checking the amount of food and liquid intake. Patients stated that at the end of the meal, the tray was taken away but they did not know precisely whether food or liquid intake was checked: <<They did not ask me, however, I did not notice if they checked the tray>> (R3);

<<I never noticed this aspect however, one day a doctor told me that I had to eat more so I think they were paying attention to these aspects>> (R9).

All respondents were completely satisfied with the administration of medication and assessment of their health status.

They stated that they found the staff to be caring and precise both on the time of drugs administration and on the measurement of vitals: <<I was amazed at how many times a day they measured the vital parameters>>(R5); <<they were always very punctual in placing my drip, and every day they checked my IV access.>>(R1); <<one day the nurse noticed that my venous access was not optimal and changed it>> (R3).

Being surgical patients, each of them had a skin incision, and again the patients highlighted the attention of nurses and doctors to the surgical wound.

The respondents emphasized that every day the dressing wound was checked and when it was found that it was not perfect and in place, it was replaced by the nursing staff or by the doctor himself.

<<every day they checked the dressing wound>> (R4); <<it happened that they changed it because it was ruined>> (R5).

From the analysis of the interviews, it emerges that the most frequently perceived missed care in the surgical areas under study are the lack of staff to introduce themselves to the inpatients during patient intake, nurses and support staff entering the room not proactively but only by calling them or ringing the bell, or for already scheduled care activities, sometimes the lack of explanation of the activities that would take place during the shift, the lack of execution or suggestion to sanitize patients' hands, as well as oral hygiene.

All other care activities investigated through the semi-structured interviews, appear to be provided finding no deficiencies.

It was not possible to analyze the data regarding the question focused on meal help, because some respondents stated that they had to respect some periods of fasting during their hospitalization or were autonomous in their food and fluid intake.

Discussion

Regarding the areas of care analyzed, the main care missed seemed to be oral hygiene belonging to the dimension of “caring principles” and the explanations of activities that would take place during the shift belonging to the dimension of “communication.”

Oral care was found to be an element of nursing activities that was often neglected, so much that patients said that they did not receive support proposals in this aspect.

In literature, failure to take care of oral hygiene is often found to be omitted [6,13,18,19] so there is concordance between the data collected and the previously reviewed literature.

The consequences of such omission turn out to be multiples, including reduction of appetite causing a potential risk of malnutrition or could generate a risk of oral mucosal infection up to the development of pneumonia.

Regarding the need of giving information by the nursing staff, it is pointed out that the patient who is in a new environment such as a hospital room needs to receive more information about daily activities and the functioning of the ward.

In this case study, respondents, stated that nurses did not always communicate effectively about how various activities would be carried out during the shift or more generally during the day.

This aspect of nursing also in the literature, turns out to be omitted frequently as evidenced by the research work of Monsivais and Guzman [14].

A further article by Kalish and colleagues [5], also brings attention to the perception of well-being during hospitalization through communicative and relational aspects, involving the inpatients through the explanation of care activities in program for them.

Also, in relevance to communication practices, it is important for professionals to introduce themselves and their roles even by taking advantage of informal moments such as entering the room or providing care activities.

From some studies such as the Sochalski [20] work, the lack of communication with the staff would imply the loss of a value to attribute to the nurse the main interlocutor role and interpreter of the patients' needs.

In conclusion, we find the proposal of hand washing to the patient belonging to the dimension of ‘caring principles’ as an activity as important as missed.

This concept, is highlighted in this research but also by other studies such as the one published by Bagnasco and colleagues [13] who described and analyzed the aforementioned issue in the Italian context.

Regarding other aspects of care, thus medication and pain medication administration, response to doorbells, mobilization, psychological support, patient education, and health assessment, in this research are reported as fully satisfied.

Limitations of the Study

The reported work encapsulates some limitations such as the monocentric and specialized setting in which the study was conducted.

The respondents were people without neuro-psychological deficits and without barriers to post-discharge mobility, so some characteristics of the target group of inpatients in the areas under study could not be included in the identified sample.

Some care activities are carried out by the professionals without always being reported to the users, therefore those surveyed, may have understood them as not conceptualized or not performed such as the assumption in the qualitative and qualitative sense of the meal.

Conclusions

Many studies in literature, focus on the experiences of care staff while this paper, focuses on the perceptions of patients who describe the acts and elements of care that are omitted or delayed, but that are essential during hospitalization. In the presented paper, one of the most omitted activities̀ according to the respondents, seems to be oral hygiene and the informational aspect, the self-presentation of the staff towards the users, the proposal of handwashing and sanitization of the oral cavity that as also widely found in many articles, is not consider as a priority aspect in care practices.

The results that emerged from this research, could be useful for nursing leaders and clinical nurses to put essential care back at the center toward their patients.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

The authors declare the absence of conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contribution

Gaia Decorato collected the interviews and processed them by analyzing the content; Chiara Tuccio composed the literature review and translated the article into English; Fabio Mozzarelli, supervised the bibliographic research and content analysis and drafted the paper.

References

- Schilling J (2006) On the pragmatics of qualitative assessment: Designing tre process for content analysis European Journal of Psychological Assessment 22: 28-37.

- Uribe M, Mun~oz C, Restrepo J, et al. (2010) Percepcio´n del paciente hospitalizado por falla cardi´aca. Institucio´n de salud 2009. Medicina UPB 29: 124-134.

- Sist L, Cortini C, Bandini A (2012) Il concetto di missed nursing care: una revisione narrativa della letteratura Assist Inferm Ric 31: 234-239.

- Kalish BJ, Williams RA (2009) Development and psychometric testing af o tool to misure missed nursing care. J Nurs Adm 39: 211-219.

- Kalish BJ, Tschannen D, Lee KH (2011) Do staffing levels predict missed nursing care? Int J Qual Health Care 23: 302-308.

- Kalisch BJ (2006) Missed nursing care: A qualitative study. J Nurs Care Qual 21: 306-313.

- Palese A, Ambrosi E, Prosperi L, et al. (2015) Missed nursing care and predicting factors in the Italian medical care s setting. Intern Emerg Med 10: 693-702.

- Duffy JR, Culp S, Padrutt T (2018) Description and factors associated with missed nursing care in acute care community hospital. J Nurs Adm 48: 361-367.

- Parise E, Rosi MR, Rancati S, et al. (2021) Missed nursing care: studio descrittivo sulla percezione degli infermieri di un grande ospedale milanese. Italian Journal of Nursing 30-35.

- See M, Chee S, Rajaram R, et al. (2020) Missed nursing care in patient education: A qualitative study of different levels of nurses' perspectives. J Nurs Manag 28: 1960-1967.

- RANCARE (2021) CA 15208 Rationing -Missing Nursing Care. An International and Multidimensional care problem 2021. RANCARE COST Action.

- Nappo A, Di Lorenzo D (2015) Missed nursing care, dotazione organica ed esiti del lavoro in ambito onco-ematologico. L'infermiere 3: 1-8.

- Bagnasco AM, Catania GL, Aiken LH, et al. (2020) Le cure infermieristiche mancate (missed nursing care) sono un dato utile ai leader infermieristici? L’infermiere 6: 1-13.

- Monsiváis M, Interial Guzmán M (2012) Percepción del pacientea cerca de su bienestar durante la hospitalización. Index de Enfermería 21: 185-189.

- Mosci D, Tarlazzi E, BIavati C (2011) Ricerca qualitativa. Chiari P, Mosci D, Naldi E. Evidence-based clinical practice. La pratica clinico-assistenziale basata sulle prove di efficacia. 2° edizione Mc GRaw-Hill Milano.

- Krippendorff K (2013) Content analysis: Al introduction to its methodology. 3° edizione Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32- item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19: 349-357.

- Fox C, Wavra T, Drake DA, et al. (2015) Use of a patient hand hygiene protocol to reduce hospital-acquired infections and improve nurses' hand washing. Am J Crit Care 24: 216-224.

- Ausserhofer D, Zandre B, Busse R, et al. (2014) Prevalence, patterns and predictors of nursing care leftundone in European hospitals: results from themulticountry cross-sectional RN4CAST study. BMJ Qual Saf 23: 126-135.

- Sochalski J (2004) Is more better? The relationship between nurse staffing and the quality of nursing careInhospitals. Med Care 42: II67-II73.

Corresponding Author

Fabio Mozzarelli, MRN, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale di Piacenza, CAP 29100, Italy.

Copyright

© 2023 Gaia D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.