The Greatest Risk to Malaysian Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Crisis: Lies of Patients

Keywords

COVID-19, Coronavirus, Healthcare Workers, Mass Gathering, Patient Behaviours, Conceal Information

In Malaysia, the first case of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported on 25 January 2020 [1]. Reported cases remained relatively low until a surge of cases emerged in March 2020, most of them linked to a 'Tabligh' religious gathering held in the Seri Petaling Mosque in Kuala Lumpur. Despite the fact that mass gatherings are known to both pose & cause major public health challenges during outbreaks [2], the gathering was held & attended by 16,000 people including 1,500 foreigners from over 20 countries as prior approval was granted by non-health related agency. As of 1 July 2020, 8640 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Malaysia have been reported; 3375 of these linked to the 'Tabligh' gathering [3,4] (approximately 39% of total cases). This resulted in Malaysia now having the highest cumulative infection tally in South-East Asia with the event emerging as a source of hundreds of new COVID-19 positive cases in Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei, Cambodia, and Thailand.

Following the 'Tabligh' gathering and the COVID-19 outbreak escalation that followed, the Malaysian government was forced to implement strict measures to contain the outbreak commencing 18th March 2020 for a period of one month, which. These measures included a Movement Control Order, bans on mass gatherings, and self-quarantine. Individuals who disobey these control measures will be subjected to various penalties under the penal code [5]. In parallel, the health director-general Dr. Noor Hisham Abdullah stressed on the importance of tracing and identifying the close contacts of 'Tabligh' attendees. Those positive need to be isolated and treated. Since implementation of these restrictions, the rate of new cases has decreased [3].

Patients lie or withhold information from their healthcare providers for various reasons [6]. This was observed in Malaysia following the event, where a number of patients who have attended healthcare services deceived or withheld information from their healthcare providers when questioned about their symptoms, contacts, travel history, and exposure risk linked to the 'Tabligh' gathering. As a consequence, a number of patients who were believed to be COVID-19 free were found to be positive for COVID-19 later on when they developed symptoms through the disease course. This placed all healthcare workers (HCWs) who might have been in contact with these patients at risk of contracting the virus. As a result, two hospitals (Pantai Hospital Laguna Merbuk and Oriental Melaka hospital) were shut down for disinfection and decontamination alongside a number of HCWs quarantined as a result of their exposure to these patients. This resulted in increased workload on the rest of HCWs; severely straining an already tired HCW especially in public health system.

During such outbreaks, frontline HCWs are subjected to increased chances of anxiety and distress given the highly contagious nature of the COVID-19 [7]. With the rapid surge in confirmed cases, enormous workload, high infection risk, inadequate and insufficient personal protection equipment (PPE), scarcity of specific drugs, wider coverage by the media and peer pressure, HCWs have been reported to experience prolonged symptoms of depression, anxiety and insomnia [7,8]. These underlying causes for distress have been attributed in part to; fear and vulnerability of self-control, self-health concerns, virus spread to their near and dear ones, alteration in work patterns and facing duplicitous patients.

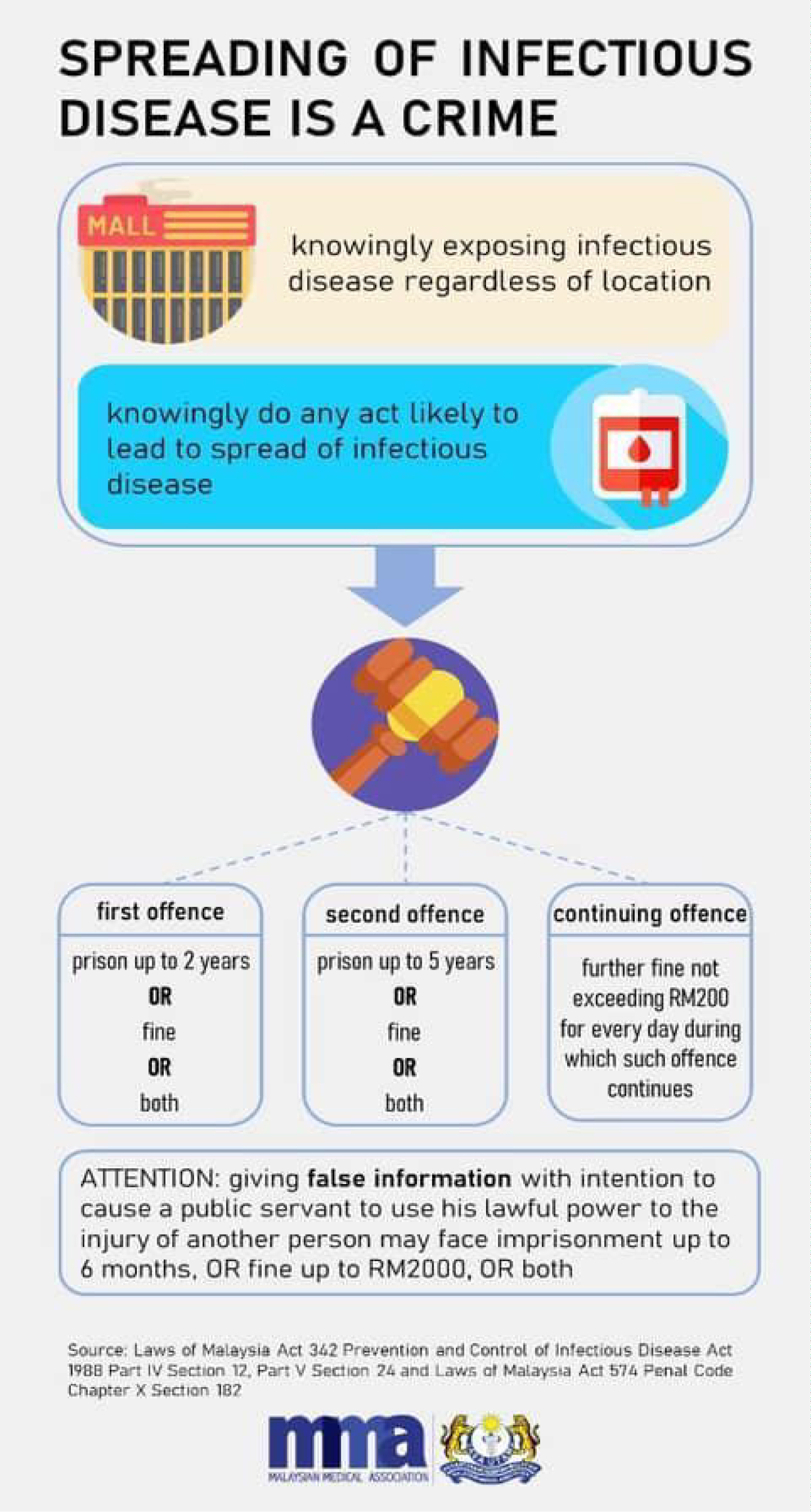

The government have taken several measures to protect HCWs, including; warning citizens of the hazards of lying to HCWs under the Malaysian penal code [9] (Figure 1), postponing all elective cases and non-urgent clinics to reduce HCW workload, providing adequate PPE, updating COVID-19 specific guidance frequently in line with international best practice, batch rotation to reduce long shifts, increasing the healthcare workforce by; remobilising HCW from other disciplines within the MOH, rounding up volunteers from NGOs and retired HCWs, and speeding up the recruitment process. MOH has also expressed the importance for HCWs to take care of their physical and mental health in and out of the workspace. However, more expansive measures are needed to protect HCWs during this outbreak, for instance; (1) Enforce strict penalties against patients who deliberately conceal information from their HCWs related to COVID-19, (2) Introducing a "Respiratory Zone" whereby all A&E staff wear PPE with anyone with/in contact with those with respiratory symptoms (this has been implemented in many Hospitals in Malaysia & should be expanded nationally), (3) Investing into means to provide HCWs with more mental, physical and emotional support (e.g. UK National Health Service staff have been provided free access to a number of wellbeing apps such as Headspace, Unmind, Sleepio & Daylight) [10], (4) More targeted and effective use of mass communications to educate public to change their behaviour within short period, with aim to reduce risk to HCW (e.g. dramatic video to show the impact of concealing information from their health care providers). Social media utilization could also be targeted to HCW to listen to their grouses and actively reassure them/their family on the steps taken to safeguard the wellbeing of HCW. Long term, instilling a sense of social responsibility and civic mindedness (e.g. In Japan, residents conscientiously wear masks if they are unwell) should be a priority.

References

- Reuters (2020) Malaysia confirms first cases of coronavirus infection.

- B McCloskey, A Zumla, G Ippolito, et al. (2020) Mass gathering events and reducing further global spread of COVID-19: A political and public health dilemma. The Lancet 395: 1096-1099.

- (2020) Latest COVID-19 Statistic in Malaysia. Ministry of health Malaysia.

- (2020) Number of cases by cluster. Kini News Lab.

- Laws of Malaysia act 342 Prevention and Control of Infectious Disease Act 1988 Part IV Section 12, Part V Section 24 and Laws of Malaysia Act 574 Penal Code Chapter X Section 182.

- DK Sokol (2014) Beware the lies of patients. BMJ 348: 382.

- J Lai, S Ma, Y Wang, et al. (2020) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open 3: e203976.

- The Lancet (2020) COVID-19: Protecting health-care workers. Lancet 395: 922.

- (2020) It's a crime to lie about travel, contact history, warns health DG. Free Malaysia Today.

- (2020) COVID-19 (Coronavirus) and your mental wellbeing. Royal College Of Nursing.

Corresponding Author

Dr. Logan Manikam, MBcHB, FFPH, PhD, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care, London, UK; Aceso Global Health Consultants Limited, 3, Abbey Terrace, London, SE2 9EY, UK, Tel: +44-7868721152.

Copyright

© 2020 Allaham S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.