Lest we Forget: Rheumatic Fever is Still Damaging Hearts

Abstract

Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD) is still a burden in many developing countries and indigenous communities within developed countries. A simple sore throat caused by the Group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus bacterium in children, teenagers and young adults, unrecognized and/or under-treated, is all it takes to begin a whole cascade of damage to the heart valves and other cardiac structures resulting in valvular stenosis and incompetence. Its complications are enormous ranging from life-long morbidity and reduced productivity, need for open heart surgery for valvular repair or replacement (often requiring long term anticoagulation), risk of strokes, increased financial burden to individuals and health systems, and many more. Many heart valve replacement surgeries even in developed countries are, still, a result of rheumatic valvular heart disease. Yet many clinicians remain very much confused as to how to recognize and prevent this condition.

Keywords

Rheumatic fever (RF), Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), Valvular heart disease, Group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GABHS) infection

Case Presentation

This 27-year-old West Indian (Caribbean) female was referred by her primary care physician because of an incidental murmur heard during a routine pre-employment medical. She, otherwise, had no complaints. She denied any symptoms of palpitations, chest pain or shortness of breath but gave a history of being told by her mother that she was diagnosed with rheumatic fever at age 9 for which monthly intramuscular Penicillin G Benzathine was commenced. At age 16, she couldn't tolerate the painful injection anymore, defaulted against medical advice but prophylaxis was later re-started with oral Erythromycin 250 mg twice daily after six years. She was never referred for specialist evaluation and had never had an echocardiogram.

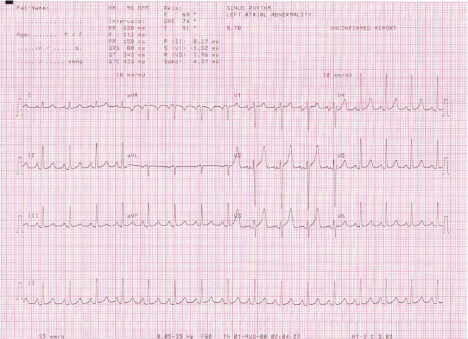

Physical examination revealed an otherwise healthy young female in no cardiopulmonary distress. Her pulse was regular at 96 beats per minute. Her blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg in the sitting position. There were no abnormal neck pulsations or venous distension seen. She, however, had a palpable first heart sound at the apex with no appreciable diastolic thrill in the left lateral position. Her apex beat was just lateral to the left mid-clavicular line at the 5th intercostal space, raising the suspicion of mild cardiomegaly. Auscultation revealed accentuated first heart sound with no appreciable murmur at the apex but there was a loud holo-diastolic murmur at the left sternal edge, heard best on asking the patient to sit up, lean forward and hold her breath. Her chest was clinically clear. Her electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with rightward axis and possible left atrial dilatation. Otherwise, there were no other significant changes (see Figure 1 below).

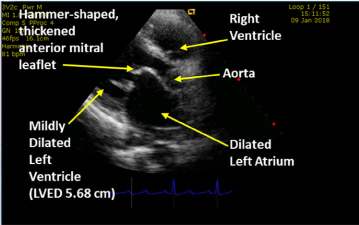

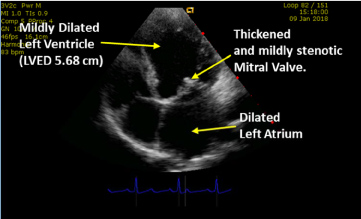

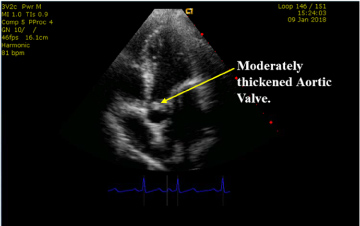

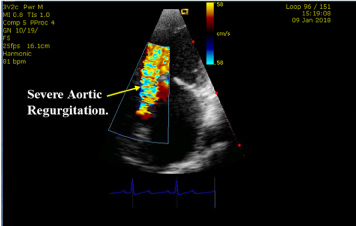

Her 2D transthoracic echocardiogram showed mixed valvular heart disease, with mild mitral stenosis (mitral valve area about 1.63 sq. cm), mild aortic stenosis (peak transvalvular vel. 2.37 m/s), severe aortic and trace mitral/tricuspid regurgitation. These findings were suggestive of rheumatic valvular heart disease. There was consequent mild left ventricular and moderate left atrial dilatation. She had borderline pulmonary hypertension (gradient 31.8 mmHg) but, otherwise, good left ventricular systolic and diastolic function (Left ventricular Ejection Fraction 65%). See Figure 2 and Figure 3 showing patient's Echo images with mild mitral stenosis, left atrial as well as left ventricular dilatation (Source: G C Ukala's Echo Library).

Figure 4 and Figure 5 below also show this patient's moderately thickened aortic valve with evidence of severe aortic regurgitation (Source: G C Ukala's Echo Library).

Clinical Impression

Though asymptomatic, this patient clearly had rheumatic valvular heart disease with multiple complications including mild aortic and mitral stenosis, severe aortic incompetence as well as left atrial and left ventricular dilatation. Without intervention, she is bound to progress to more severe disease with worsening pulmonary hypertension and its attendant complications.

Discussion

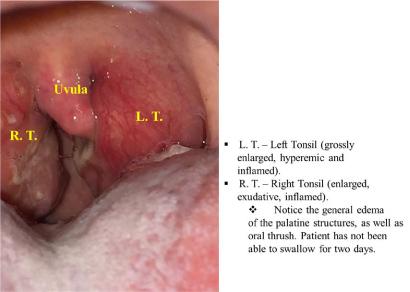

"Rheumatic fever is an autoimmune inflammatory disease that may result from untreated group A beta hemolytic streptococcal infection such as pharyngitis, scarlet fever and, in some cases, skin sepsis" [1,2]. The autoimmune response occurs because of cross reactivity between streptococcal and human proteins [3]. In many cases it follows an exudative tonsillo-pharyngitis caused by group A beta hemolytic streptococci as shown above in another patient (aged 15) who presented acutely with sore throat, fever and joint pains (see Figure 6 above).

Though predominantly seen in children (ages 5-15 years), rheumatic fever may be seen in early adulthood. Its most feared complication is that of rheumatic heart disease following recurrent bouts of acute rheumatic fever [1]. "About 60% of all patients with acute rheumatic fever will develop carditis and join the over 15 million patients (worldwide) with rheumatic heart disease" [1,2]. Inflammatory changes in the heart may include pericarditis and/or myocarditis and/or endocarditis - or all of these (known as Pancarditis).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of rheumatic fever is hampered by the lack of a "gold-standard" or single test confirmatory for the disease [1] but the well-known Duckett Jones criteria [4] which recommends the presence of two major or one major and two minor criteria, in addition to evidence of recent streptococcal infection, serve as a useful guide for a firm diagnosis. Major criteria include evidence of carditis, polyarthritis, chorea, erythema marginatum or subcutaneous nodules while the minor criteria include presence of fever, arthralgia, previous rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease, acute phase reactants (such as leucocytosis, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ESR, and raised C-reactive protein, CRP) or prolonged PR interval on electrocardiogram (ECG) [1,4]. Evidence of recent streptococcal infection is supported by increased anti-streptolysin O titre (ASOT) or other streptococcal antibodies, positive throat culture for Group A beta-haemolytic streptococci, positive rapid direct Group A strep carbohydrate antigen test or recent scarlet fever (mostly 2-10 years-old with sore throat, fever > 101 ℉, bright red sandpaper-like rash in neck, chest and axillae) [1,4].

Management

This patient was counselled on the importance of compliance with her secondary antibiotic prophylaxis and need to avoid, if possible, reinfection with the causative organism. She was also referred to the Cardiothoracic unit for evaluation and follow-up care.

Once diagnosed, treatment of rheumatic fever should be as recommended in most standard textbooks, but emphasis must be placed on awareness, prompt treatment of all suspected streptococcal infections and prevention of recurrent infections which are responsible for the cardiac complications that often result in a life time of misery.

Conclusion

Though rheumatic fever is no longer a serious health problem in the first world countries, and its incidence may be on the decline in developing countries, it still accounts for significant valvular pathologies. Each child or young adult diagnosed with structural valvular heart disease of rheumatic origin, often requiring valvular repair or replacement, suffers an otherwise preventable long-term tragedy. It should not be forgotten that rheumatic heart disease still wreaks havoc especially in developing countries around the world. Emphasis should continue to be placed on awareness, recognition and prevention of this condition.

Declaration of Interests

No conflict of interests declared.

Consent

Written consent obtained from patient.

References

- Ukala GC (2014) How is rheumatic fever acquired? Clinical dialogues in hospital medicine, 146.

- Rheumatic Fever: Mark R Wallace, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Chief Editor: Burke A Cunha, MD.

- Guilherme L, Fae KC, Oshiro SE, et al. (2007) T cell response in rheumatic fever: Cross reactivity between streptococcal M protein peptides and heart tissue proteins. Curr Protein Pept Sci 8: 39-44.

- (1992) Guidelines for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever. Jones Criteria, 1992 update. Special Writing Group of the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young of the American Heart Association. JAMA 268: 2069-2073.

Corresponding Author

GC Ukala, FRCP Edin, Consultant Physician & Head of Department, Internal Medicine, Mandeville Regional Hospital; Clinical Director, Integrated Medical Services Limited, Mandeville and Author, Clinical Dialogues in Hospital Medicine, Jamaica.

Copyright

© 2020 Ukala GC, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.