Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome following Exchange Transfusion and Steroids in a Child with Sickle Cell Disease: A Case Report

Abstract

Background: Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is clinical and radiographic entity with several identified triggers, characterized by severe headaches and a reversible "string of beads" appearance of cerebral vessels on vascular imaging.

Methods: We report a case of a child with Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) who developed RCVS.

Results: A 5-year-old female with SCD presented with thunderclap headaches, followed by stabbing headaches after receiving an exchange transfusion and prednisolone. She developed ischemic infarcts in the left parietal and right paramedian frontal and parietal lobes. Vascular imaging revealed arterial luminal narrowing and irregularity in bilateral anterior and posterior circulations. No inflammatory causes were found. At 3-month follow-up, vascular imaging improved with no recurrence of headaches or seizures.

Conclusion: RCVS is rarely reported in SCD. However, it should be considered in patients with SCD presenting with severe headaches. In such cases, early vascular imaging is important for prompt diagnosis of RCVS.

Keywords

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, Sickle cell disease, Thunderclap headache, Seizure, Stroke

Introduction

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) is characterized by thunderclap headaches with or without focal neurological symptoms and a reversible "string of beads" appearance of cerebral vessels on vascular imaging due to alternating, simultaneous dilatation and constriction [1]. Common predisposing factors include female sex, history of migraine headaches and use of vasoactive substances [2]. One-third to half of patients with RCVS develop ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, isolated or in combination, which can result in focal neurological deficit or seizures [3]. Despite the precipitous onset and frequently ominous cerebral angiographic appearance, over 90% have excellent clinical outcome [3].

The average age of onset of RCVS is between 20 and 50-years [1,3]. RCVS is uncommon in childhood, with 29 pediatric cases currently described (Supplementary Material) [4-6]. In this report, we present a case of a child with sickle cell disease (SCD) who, after receiving exchange transfusion and prednisolone, presented with thunderclap headaches followed by stabbing headaches, and was diagnosed with RCVS complicated by ischemic infarcts.

Case

A 5-year-old, right-handed, developmentally normal, female of African descent was diagnosed with SCD at three years of age (HbSS genotype). She was the product of an unremarkable pregnancy and delivery. Family history was significant for SCD in her 8-year-old sister and maternal uncle. Her SCD course was complicated by recurrent acute-on-chronic splenic sequestration and repeated vaso-occlusive crises, resulting in regular exchange transfusions. She subsequently developed allo-immunization to the Duffy antigen and delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction.

Three days prior to presentation, she received an exchange transfusion, with a rise in hemoglobin (Hgb) from 48 g/L to 88 g/L. Prednisolone was commenced to mitigate the delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction. She presented to hospital with three sudden-onset incapacitating headaches lasting 10 minutes, over the preceding 24 hours, triggered by micturition. In the Emergency Department, vital signs and physical examination were normal and she was admitted for observation and investigations.

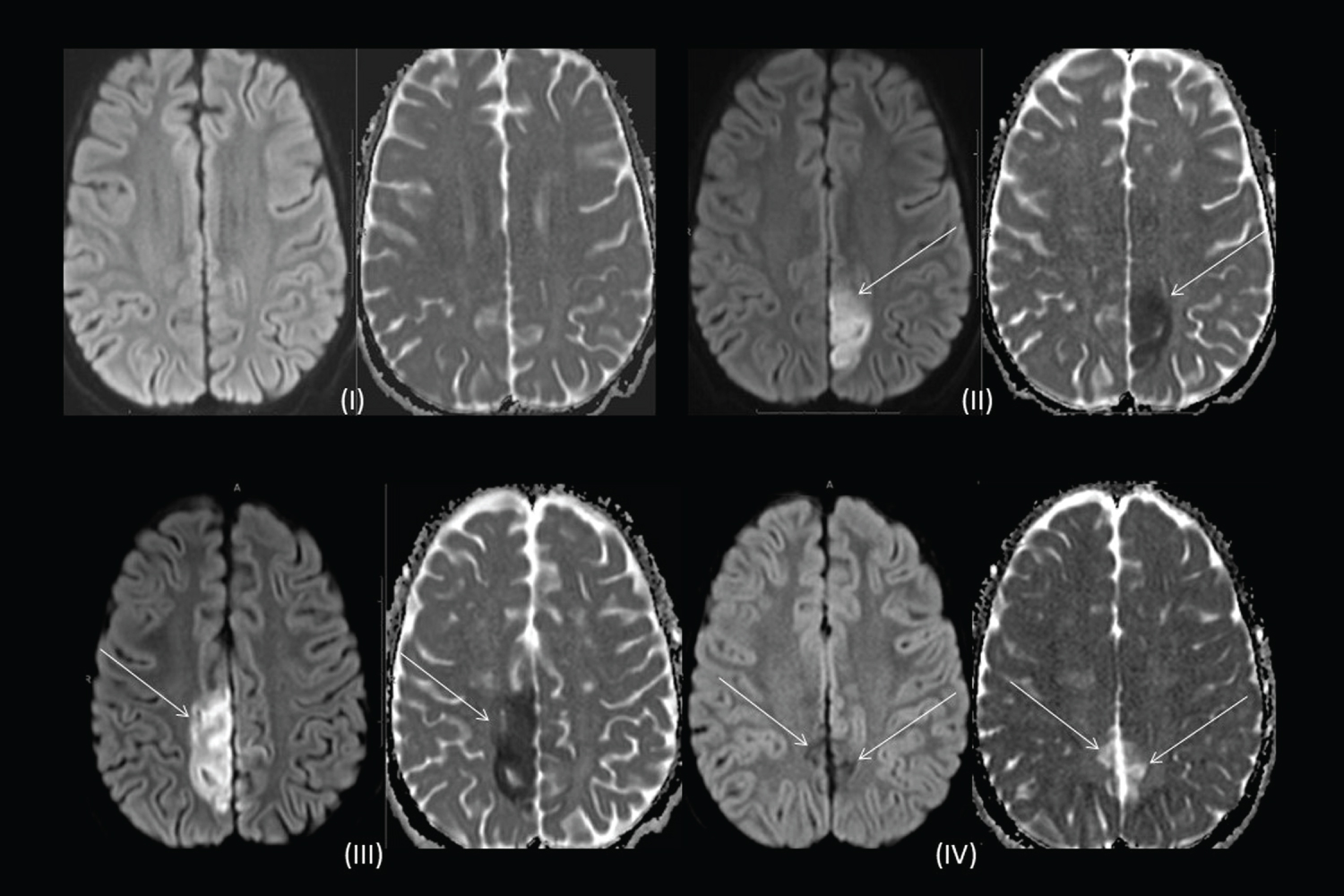

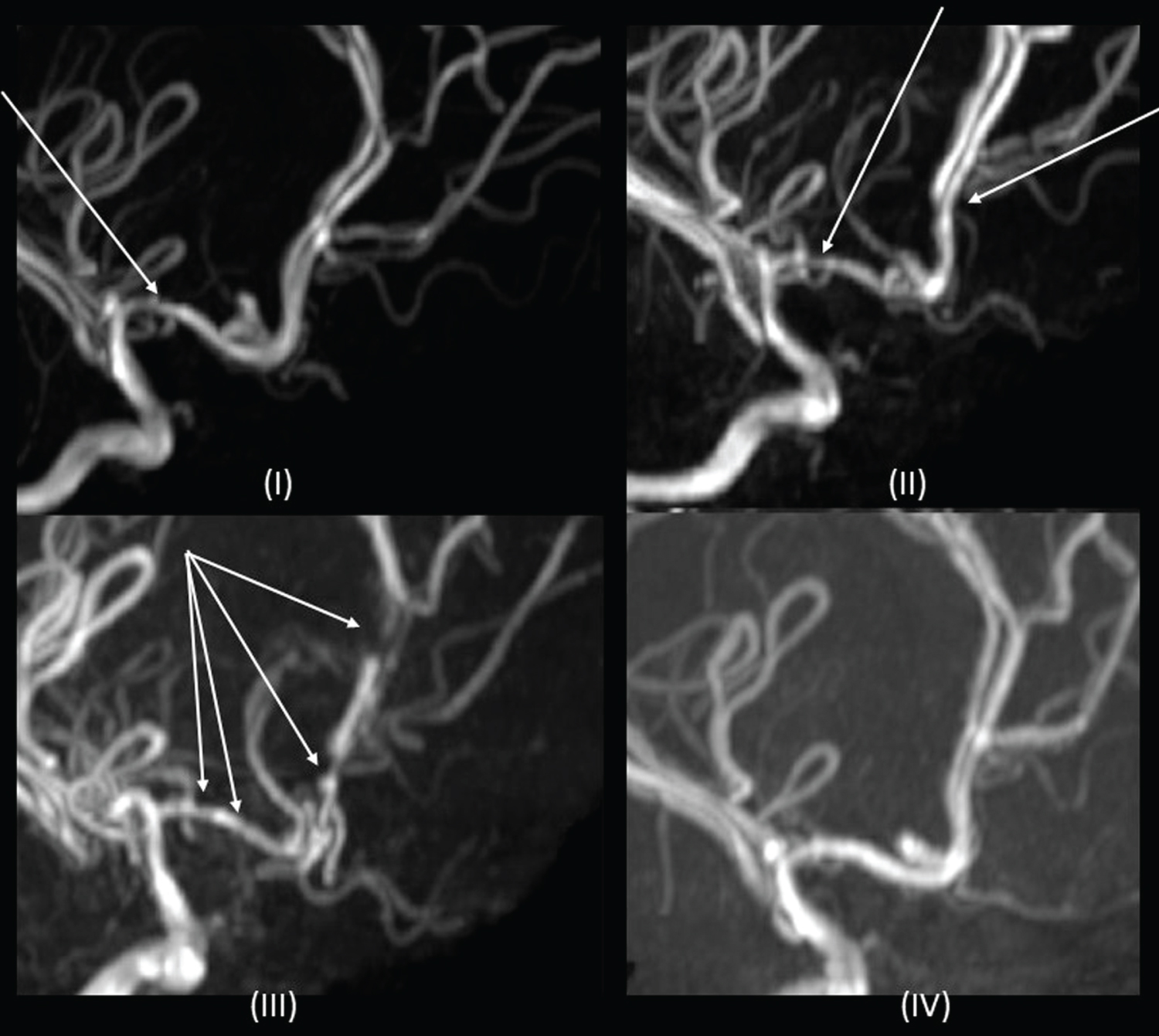

Overnight, a similar 10 minute headache recurred which was associated with a spike in blood pressure (BP) to 124/93. An urgent MRI and MRA revealed mild luminal irregularities in bilateral anterior cerebral arteries (ACA) and right middle cerebral artery (MCA) that were thought to be related to early cerebral vasculopathy of SCD. No clear cause for her headaches was identified and repeat imaging was recommended in six-months (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In hospital, her BP's were in the 50th percentile for age.

Over the next two days, her headaches changed in nature, characterized as sudden, unexpected sharp, stabbing head and eye pain that lasted for seconds. They were less severe than her initial headaches and she had no accompanying autonomic features. As these headaches had features of primary stabbing headache (PSH), and no etiology was determined, a trial of indomethacin was attempted for 48-hours, without improvement of headaches.

On day five of admission, she developed seizures characterized by clonic movements of the right leg and right hemi-field visual impairment, followed by a right-sided Todd's paralysis. On EEG, there was left hemisphere suppression. MRI brain revealed a four-centimeter diameter ischemic infarct in the left parietal lobe, with punctate foci within the left posterior cerebral artery (PCA) territory (Figure 1). Vascular imaging showed worsening of previous arterial luminal narrowing and irregularity, affecting both anterior and posterior circulations. Caliber of some vessels appeared increased, implying dynamic vessel changes, raising the diagnosis of RCVS (Figure 2). Headaches continued for 24 hours after this event and then dissipated. Levetiracetam was initiated for seizure management. An ophthalmology assessment, lumbar puncture and primary/secondary CNS vasculitis workup were unrevealing.

Ten days post-admission, prednisolone was weaned, as it was a potential trigger for RCVS. On day eleven, she developed left-sided clonic seizures. MRI brain showed new infarct in the right ACA territory involving the paramedian frontal and parietal lobes (Figure 1), and global worsening of multifocal arterial irregularity and stenosis (Figure 2). After Nephrology consultation, given concern for underlying systemic vasculopathy and risk of renal injury, nifedipine was started on day 13 of admission for treatment of RCVS.

To avoid further splenic sequestration and reduce amount of exchange transfusions, on day 16 of admission, the patient underwent laparoscopic total splenectomy without complication. After 37 days in hospital, the patient was discharged home.

At three-month follow-up, MRA demonstrated residual multi-vessel irregularity and stenosis that was markedly improved compared to previous studies and no new areas of stenosis (Figure 2). Levetiracetam was discontinued. At 2-year follow-up, the patient has MRC grade 4+/5 weakness in the left leg in an upper motor neuron distribution; not impacting her functioning and the remainder of the neurological examination is normal. On neuropsychological evaluation, she is diagnosed with moderately severe specific learning disorders in reading and written expression, requiring intensive support. All other cognitive domains are within age-expectations. There has been no recurrence of headache or seizures.

Discussion

In children with SCD, especially the HbSS genotype, ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes are significant complications that impact morbidity and mortality. However, despite the increased risk of cerebrovascular complications with SCD, RCVS is not common; with only two previous reported cases in the literature [7,8]. This paucity of cases may be explained by the fact that RCVS is an under-recognized condition, especially in the pediatric population, as most cases eventually resolve, not all have focal neurological deficits, vascular imaging may not be performed or neuro-imaging may be initially normal.

The pathophysiology of RSCV is poorly understood. It is postulated that abnormal discharge of sympathetic activity plays a role in RCVS, as the affected vessels have rich sympathetic innervation [9]. Abrupt stretching of the arterial wall is thought to be responsible for the typical thunderclap headache. This is followed by more proximal medium to large artery involvement with subsequent increased risk of cerebral ischemia [9].

A precipitating factor for RCVS is observed in up to 60% of cases [2], including vasoactive medications and, rarely, blood products [5,10]. The two previous reports of RCSV and SCD include an 18-year-old female with unilateral posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) and RCVS after transfusion and an 8-year-old male with PRES and RCVS after transfusion and steroid treatment [7]. Although our patient did not develop PRES, similar to both other reported cases, our patient received transfusions prior to symptoms, with a significant rise in Hgb, which may have exacerbated the risk.

Blood transfusions are described as a precipitant of RCVS. In SCD, cerebral blood flow is increased and patients may be unable to fully compensate by autoregulation due to the changes in blood volume or increased viscosity [11]. Excessive blood volume after transfusion may itself lead to systemic hypertension with subsequent dysregulation of cerebral blood flow. A sudden increase in viscosity during blood transfusion may precipitate an acute vascular endothelium dysfunction leading to vasoconstriction, and that in PRES is particularly evident in posterior circulation [11].

Our patient received prednisolone two days prior to symptom-onset, similar to the other pediatric case of RCVS and SCD [7]. RCVS after steroid administration is also reported in a child with refractory cytopenia of childhood and a child with cerebellitis [4,5]. The role of steroids as a trigger for RCVS is not fully elucidated. Steroids may play a role in the development of RCVS by increasing blood pressure or through other effects on vascular tone [11]. Steroids have a known association with PRES and the pathophysiology of RCVS and PRES overlap; 9-14% of patients with RCVS may have PRES [3,7,8]. It is postulated that in RCVS, glucocorticoids may in fact induce worsening by potentiating the effects of vasoconstrictors such as norepinephrine, angiotensin II, endothelin, and others, as well as their direct actions on vascular smooth muscle cells [10].

Our patient initially presented with thunderclap headaches. In a systematic review, headaches are the most common symptom of RCVS present in 93.2% of patients, with thunderclap headaches being most common [3]. However, any type of headache can occur. Our patient's headaches initially occurred with micturition. Valsalva maneuvers, which may be associated with micturition, have been implicated in triggering thunderclap headaches in RCVS in 20-30% of cases [9]. Notably, our patient later developed stabbing headaches. Primary stabbing headaches are characterized by head pain occurring spontaneously as a single stab or series of stabs that lasts only for a few seconds, occur with irregular frequency and are not associated with cranial autonomic symptoms [12]. Primary stabbing headaches can only be diagnosed in the absence of organic disease of underlying structures or of the cranial nerves. However, it is known that stabbing headaches can occur secondary to intracranial pathology, including tumors, meningoencephalitis and arteriovenous malformations. Prior to the diagnosis of RCVS, our patient was treated with indomethacin, with little benefit. Our patient demonstrates that secondary stabbing headaches can occur with RCVS.

Our patient received nifedipine as a treatment option after her second infarct. However, the beneficial effect of calcium channel blockers on cerebral vasoconstriction remains unclear [3]. Given the relatively good safety profile, use of calcium channel blockers in severe RCSV may be justified. This case highlights the importance of considering RCVS in the differential diagnosis of patients with SCD presenting with severe or non-habitual headaches. In such settings, vascular imaging should be considered early, even in the absence of focal neurological deficit, especially if there are known RCVS risk factors, such as transfusions or steroids, for prompt diagnosis and management of RCVS.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. John Wu and the hematology team for their care of this patient. We thank Dr. Adam Kirton for his input on this patient.

Author Contributions: Matthew Tester and Anita Datta drafted the manuscript and reviewed it for important intellectual content. Matt Tester prepared Table S1 for the supplementary material. Maksim Parfyonov and Paul Webb reviewed and edited the manuscript for important intellectual content assisted with preparation of the figures.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Research Ethics and Patient Consent

The patient provided consent for the case to be published.

References

- Ducros A, Bousser MG (2009) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Pract Neurol 9: 256-267.

- Ducros A, Fiedler U, Porcher R, et al. (2010) Hemorrhagic manifestations of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: Frequency, features, and risk factors. Stroke 41: 2505-2511.

- Song TJ, Lee KH, Li H, et al. (2021) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: A comprehensive systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 25: 3519-3529.

- Coffino SW, Fryer RH (2017) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome in pediatrics: A case series and review. J Child Neurol 32: 614-623.

- Desai N, Shah N, Udani V, et al. (2022) Pediatric reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: Two unique cases with a review of all reported children. J Pediatr Neurol 20: 41-47.

- Lagace M, Graeber B, Huh L (2021) Child neurology: Pheochromocytoma unveiled by reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome in a child with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology 96: 79-82.

- Regling K, Pomerantz D, Narayanan S, et al. (2021) Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and sickle cell disease: A case report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 43: e95-e98.

- Zuccoli G, Nardone R, Rajan D, et al. (2018) Nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in sickle cell disease: Description of a case and a review of the literature. Neurologist 23: 122-127.

- Dodick DW, Brown RD Jr, Britton JW, et al. (1999) Nonaneurysmal thunderclap headache with diffuse, multifocal, segmental, and reversible vasospasm. Cephalalgia 19: 118-123.

- Singhal AB (2004) Cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Top Stroke Rehabil 11: 1-6.

- Prohovnik I, Pavlakis SG, Piomelli S, et al. (1989) Cerebral hyperemia, stroke, and transfusion in sickle cell disease. Neurology 39: 344-348.

- (2018) Headache classification committee of the international headache society (IHS) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd Cephalalgia 38: 1-211.

Corresponding Author

Anita N Datta, MD, FRCPC, CSCN Diplomate (EEG), Clinical Associate Professor of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, BC Children's Hospital, 4480 Oak Street, Vancouver, BC, V6H 3N1, Canada, Tel: 604-875-2121, Fax: 604-875-2285

Copyright

© 2022 Tester MA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.