Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension Presenting with Chiari Malformation and Hydrocephalus Associated With Lumbar Pseudoarachnoiditis

Abstract

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) is a rare occurrence, especially in children. In the pediatric population, three cases of Chiari malformation in children and no cases of hydrocephalus due to SIH have been discussed in the literature. We present two patients under the age of five who presented with imaging concerning for the need for neurosurgical intervention later found to be due to SIH that resolved spontaneously. These cases are the fourth case of Chiari and the first case of hydrocephalus due to SIH in the pediatric population presented in the literature. In addition, they are the youngest reported cases of these conditions and the only cases to resolve with conservative measures. Most cases of SIH require intervention, but since our cases resolved spontaneously in a relatively short period of time, this phenomenon may be more prevalent than is recognized in the pediatric population. Cerebellar subdural hygromas and clumping of the lumbar nerve roots were crucial findings in determining the accurate diagnosis. We caution neurosurgeons to look closely for signs of intracranial hypotension when establishing a diagnosis and especially prior to surgical decisions.

Keywords

Intracranial hypotension, Chiari malformation, Hydrocephalus, Subdural hygromas, Case series

Introduction

Spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH) occurs in approximately 1 in 50,000 in all ages [1]. The prevalence of SIH in the pediatric population is not clear as it is even rarer, particularly in the first decade of life. One center reported that only about 5% of their SIH cases occurred in patients under 18-years of age [2]. SIH can present as other neurosurgical pathologies, leading the practitioner to unnecessary workup and interventions. The typical presentation of SIH is orthostatic headaches that may worsen with Valsalva maneuvers, but can include vomiting, vision changes, and dizziness. Rarely, SIH can present mimicking other neurosurgical entities. Patients with various connective tissue disorders are at higher risk of developing SIH [2]. While multiple reports of SIH presenting as Chiari malformation have been reported in adults, only three prior pediatric cases have been published. No prior cases of SIH presenting with the clinical and imaging findings of hydrocephalus in a child have been found. In many cases of SIH, intervention is required to resolve symptoms; but no prospective study comparing conservative and procedural treatments has been performed [3]. Headache relief may be more likely in adult patients who have treatment compared to conservative therapy [4]. We present two cases of children less than five years of age who presented with two different common pediatric neurosurgical entities, Chiari 1 malformation and hydrocephalus, but instead, suffered from SIH that resolved without intervention. These cases are much younger and resolved spontaneously in contrast to the already reported cases in the literature. A thorough history and careful review of the imaging were crucial for identifying the correct pathology in these cases.

Illustrative Cases

Case 1

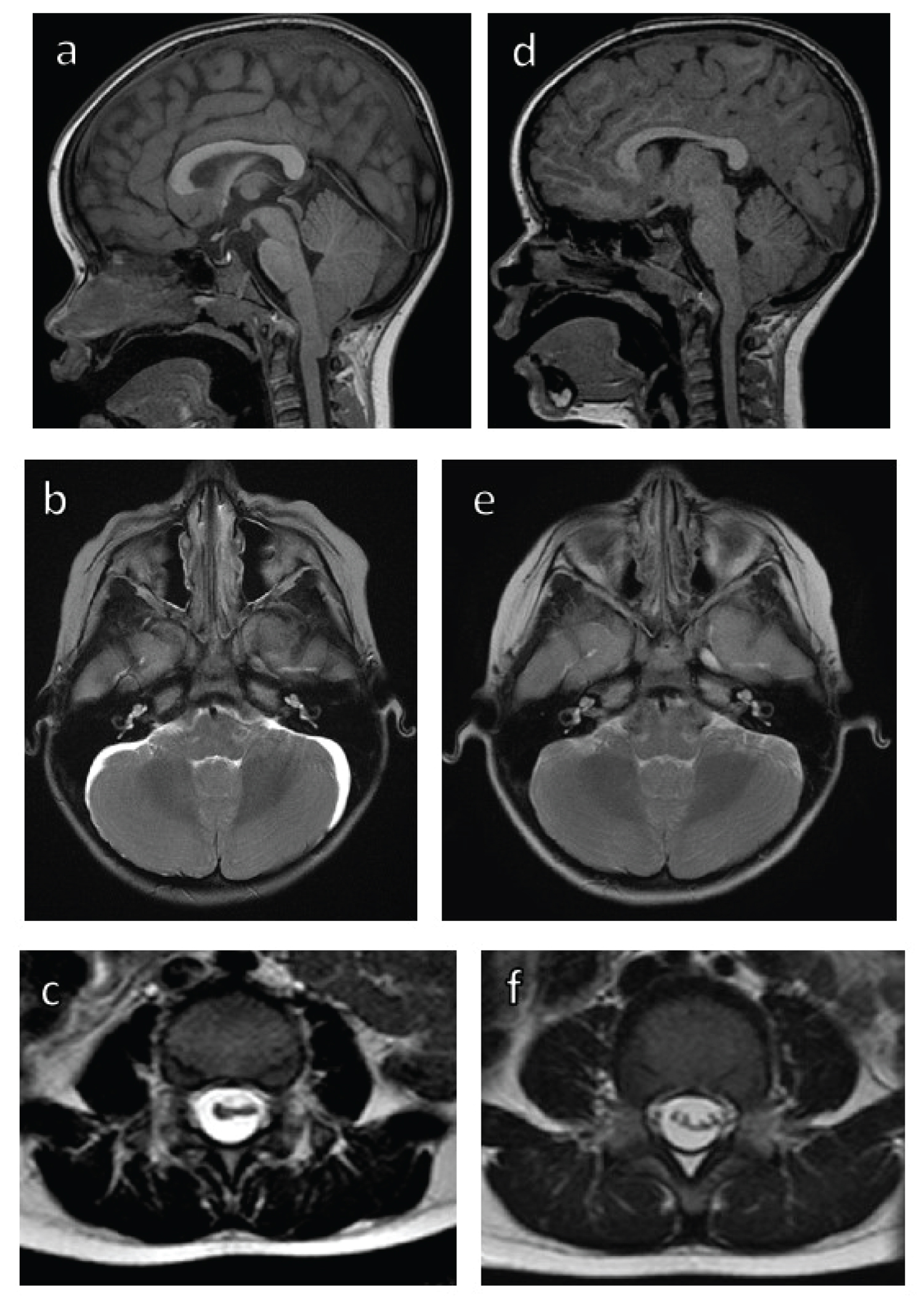

Four-year-old female with no significant past medical history was referred for newly discovered Chiari 1 malformation. She did not have any signs of connective tissue disorder such as joint laxity, elongated digits, rashes, or other associated findings. She complained of occipital headaches and vomiting that started after riding a rollercoaster at a local amusement park several times in one day. The headaches and vomiting occurred multiple times daily without any identified triggers, but would worsen when upright. After several days, the headaches and vomiting resolved; however, given the unusual presentation, the patient's pediatrician ordered an MRI brain which was obtained two weeks after symptoms started. The MRI showed 9 mm of tonsillar descent with crowding of the foramen magnum and a pronounced cervicomedullary kink (Figure 1a). Neurosurgery's review of the MRI brain showed bilateral cerebellar subdural hygromas, which were not commented on by radiology, concerning for intracranial hypotension (Figure 1b). Lumbar spine MRI showed crowding of the nerve roots with a circumferential subdural fluid collection (Figure 1c). The patient's neurological exam was unremarkable and since her headaches had resolved, no surgery or further diagnostic workup such as a myelogram or lumbar puncture was planned. Two months later, repeat imaging revealed the subdural hygromas had resolved, the cerebellar tonsils had ascended 5 mm (now 4 mm below the foramen magnum), and cervicomedullary kink had improved (Figure 1d and Figure 1e). In the lumbar spine, the nerve roots were much less clumped together (Figure 1f). At follow-up three months later, the patient's symptoms remained resolved.

Case 2

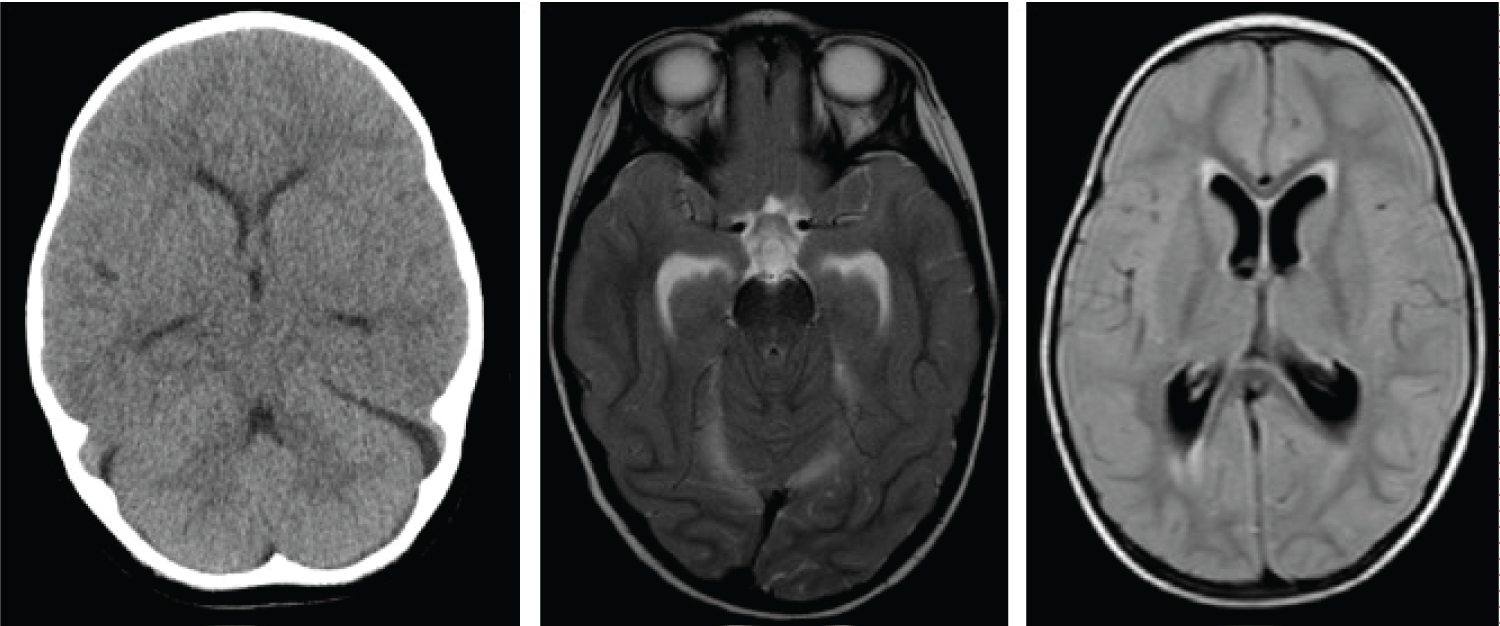

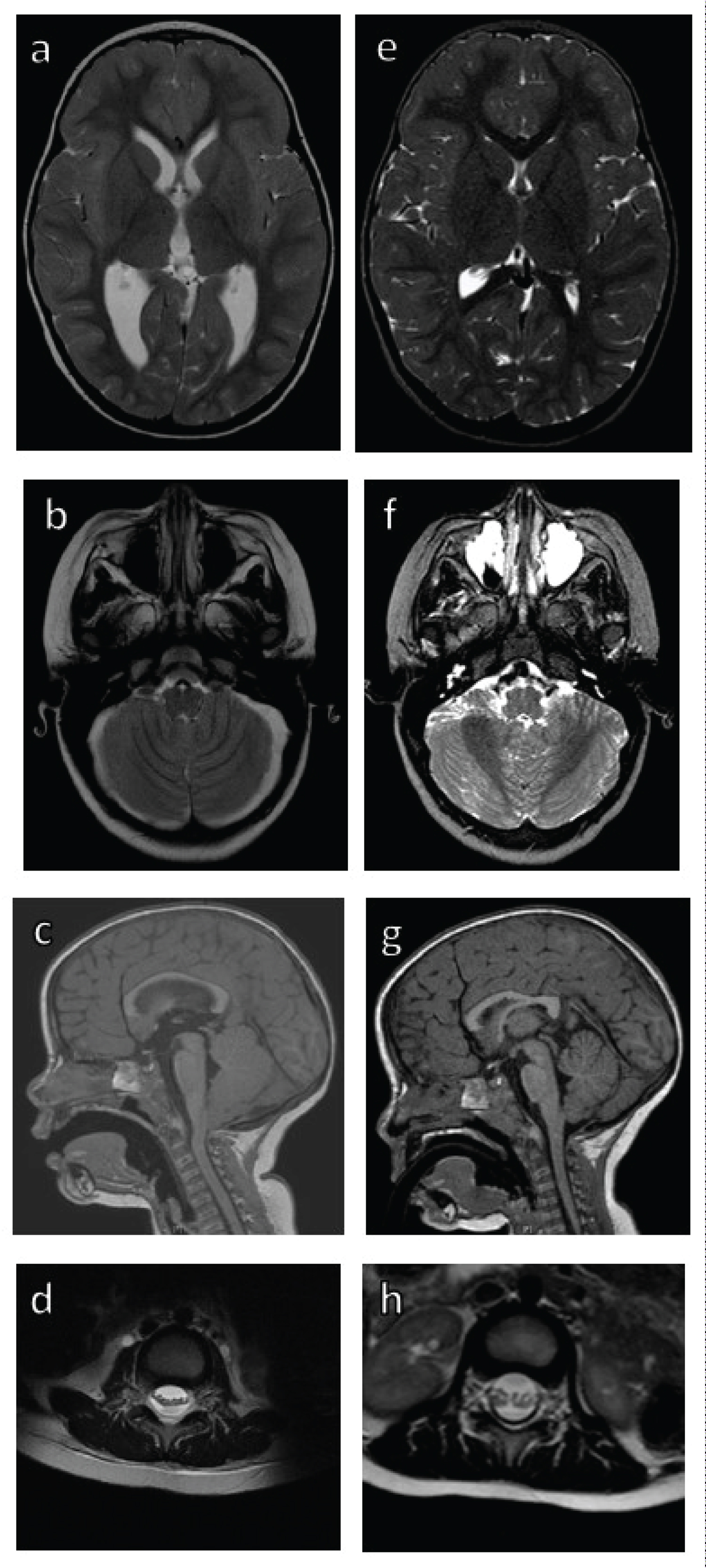

Two-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented to an emergency department with five days of headache and vomiting while vacationing out-of-state. There, she had a CT brain that was read as normal, but again after later review by neurosurgery, showed bilateral cerebellar hygromas (Figure 2a). A lumbar puncture was performed after CT at initial presentation due to the outside hospital's concern for meningitis which was ruled out. Opening pressure and amount drained was not recorded at the outside facility, but drainage likely worsened the condition as the pressure was lowered further. The patient was given antibiotics for a urinary tract infection and sent home. When she did not improve, she presented to our pediatric emergency department. At this time, she had suffered from ten days of headache, vomiting, and fatigue. Her headache was worse when lying down. MRI brain was concerning for hydrocephalus with transependymaledema, bilateral cerebellar hygromas, mild cerebellar tonsillar ectopia, increased prominence of the prepontine and premedullary cisterns, and mild cervical cord kinking (Figure 2b, Figure 2c, Figure 3a, Figure 3b and Figure 3c). This constellation of findings was concerning for fourth ventricular outflow obstruction. The patient did not have any neurological deficits. MRI of the spine revealed centralization of the lumbar nerve roots concerning for subdural fluid collections in the lumbar spine (Figure 3d). Patient was observed for two days with no treatment except for IV hydration and her headaches and vomiting resolved. Six months later, MRI showed resolution of hydrocephalus, cerebellar subdural hygromas, and great improvement in clumping of the lumbar nerves (Figure 3e, Figure 3f and Figure 3h). In addition, her cervical kinking and prominence of midline cisterns improved and her cerebellar tonsillar ectopia resolved (Figure 3g). At last follow-up six months after her initial presentation, the patient was doing well with continued resolution of symptoms.

Discussion

The typical presentation of SIH is orthostatic headaches that may worsen with Valsalva maneuvers [5]. Other symptoms include vomiting, blurred vision, tinnitus, vertigo, or balance difficulties. While direct measurement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure is the main diagnostic study, there are five main imaging characteristics on MRI that may point to SIH: Subdural fluid collections (particularly in posterior fossa), sagging or downward displacement of brain, meningeal enhancement, venous engorgement, pituitary hyperemia [5]. SIH in the pediatric population is uncommon and SIH in the first decade of life is limited to very few case reports [2]. A retrospective review showed 24 pediatric cases of SIH over an eleven-year period (out of a total of 450 patients), none of which showed evidence of Chiari malformation or hydrocephalus as in our patients [2]. Only two of the 24 patients were under the age of ten and both suffered from a connective tissue disorder. All but one of the 24 cases required epidural blood patch, fibrin glue patches, or operative repair for resolution of their symptoms. Both of our cases were in the first decade of life and resolved spontaneously, one prior to their neurosurgical consultation. Based on this, SIH in children may be more common than is recognized as they may improve prior to evaluation.

Multiple reports of Chiari malformation in the setting of SIH have been reported in adults [6,7]. The only other pediatric cases in the literature were in adolescents (ages 12-15) and all three required epidural blood patches before symptoms resolved, in contrast to both of our cases which resolved spontaneously [1,8,9]. One of the three suffered from Marfan syndrome, but the other two did not have a connective tissue disease. The exact reason why SIH may cause an acquired Chiari malformation is not fully elucidated. One center noted Chiari malformations in seven of thirty-five SIH adult patients over a ten-year period [6]. The only unique aspect to these patients was the patients with Chiari suffered from SIH for a much longer period of time (months to years) compared to those without Chiari. This study noted that these patients showed more overall brain sagging with loss of CSF cisterns, brainstem distortion, and occasional subdural hygromas compared to the "typical" Chiari appearance on MRI. One theory is the loss of CSF in the spinal subarachnoid space causes a pressure difference or a sump effect and the cerebellar tonsils are pulled down. In contrast to the other reported cases, our patient had symptoms for only two weeks before her MRI showing a Chiari malformation was obtained. The previously reported pediatric cases had symptoms for at least three months (range 3-18 months) which is similar to all the adult cases reported by Atkinson, et al. [1,6,8,9]. Our case illustrates Chiari malformation can be seen earlier in the course of SIH than previously described. We do not know why our patient developed SIH, but in most cases, the cause is never uncovered and the mechanism is still not understood [5]. Our hypothesis is our patient had an asymptomatic subarachnoid bleb or weakness in the spinal meninges that ruptured while riding the rollercoaster, triggering the intracranial hypotension. This is the youngest reported case of SIH presenting as Chiari malformation and the first reported case of any age to resolve spontaneously. Summarizes the known pediatric cases of Chiari 1 malformation or hydrocephalus secondary to SIH.

The second case presents the only known case of pediatric SIH presenting with clinical and imaging characteristics of hydrocephalus. There are case reports of children with shunted hydrocephalus presenting with low-pressure ventriculomegaly after lumbar puncture, but our patient was not shunted [10]. We speculate that there was a spontaneous CSF leak in the spine that caused cerebral sagging that may have caused ventricular outflow obstruction causing the ventriculomegaly and transependymal edema; however, an obvious obstruction was not appreciated on imaging. There was mild cervical cord kinking along with increased prominence of the prepontine and premedullary cisterns which was concerning for fourth ventricular outflow obstruction. Another hypothesis is the loss of spinal subarachnoid CSF created a pressure differential where the pressure in the subarachnoid space was much lower than the pressure in the ventricles causing the ventricles to expand. This case also resolved without intervention aside from bedrest and hydration.

Conservative treatments such as bedrest and hydration are typically employed as first line treatment for SIH. While no prospective comparison of treatments has been done, retrospective reviews indicate conservative measures fail in the majority of cases [3,4,11]. One study of 53 adult patients reported that 81% failed conservative treatment and required epidural blood patching [4]. In addition, those patients who received epidural blood patches reported greater improvement in their headaches compared to those with supportive measures alone. In another study, only 8% of 178 adult patients experienced complete resolution of symptoms with conservative treatment [11]. In the pediatric population, Schievink, et al. reviewed all cases of SIH at a single institution in patients 19-years of age or younger over an eleven-year period [2]. Out of twenty-four cases, only one patient did not require any surgical intervention for a CSF leak. This fourteen-year-old male experienced symptom resolution with conservative measures only, but headache recurred seven months later due to a subdural hematoma next to a middle fossa arachnoid cyst that had been incidentally discovered earlier. Not only did both of our cases resolve with conservative care, both experienced complete symptom resolution with great outcomes. Since we do not know why our patients developed SIH initially, it is difficult to know why they spontaneously resolved. If it was due to a spontaneous rupture of the arachnoid, we would surmise this small defect spontaneously sealed itself resulting in a restoration of normal intracranial pressure and resolution of symptoms. It is possible that SIH may occur more often in the pediatric population than is recognized as they may resolve spontaneously after a short course of symptoms before any workup or imaging may be initiated.

In both of our cases, subdural hygromas, one of the main SIH characteristics on MRI, were a critical finding to lead to the correct diagnosis and avoiding unnecessary surgery. In our cases, the hygromas resolved when the other imaging findings resolved as well. Another imaging finding in our cases was lumbar nerve root clumping. This has been reported in spontaneous and traumatic intracranial hypotension and is hypothesized to be from collapse of the spinal subarachnoid space, resulting in subdural CSF collections [12]. The term "pseudoarachnoiditis" has been connected to the appearance of the spinal nerve roots in SIH as they can show enhancement along with clumping, but the enhancement is not always present as in our cases. Both of our cases exhibited this phenomenon which showed improvement, but not resolution, on short-term follow-up which suggests brain findings improve prior to spinal manifestations of SIH. The finding of lumbar pseudoarachnoiditis shows how important it is to obtain MRI of the lumbar spine in newly diagnosed Chiari patients or those with unusual or complex presentations in order to assess for signs of other pathologies such as SIH or tethered spinal cord.

Conclusions

We present two cases of pediatric SIH that presented with associated neurosurgical entities: Chiari malformation and hydrocephalus. One is the youngest known case of SIH associated Chiari malformation and the second is the only known case of SIH associated hydrocephalus, both of which resolved spontaneously. SIH can appear as other neurosurgical entities which may cause delayed treatment or unnecessary surgeries if not properly identified. Cerebellar subdural hygromas and clumping of the lumbar nerve roots are crucial findings that point to SIH as the true diagnosis. "Pseudoarachnoiditis" is an unusual finding that in the setting of possible CSF disorders that almost definitively points to SIH. Acquired Chiari malformation may develop early in the course of SIH and hydrocephalus can occur in SIH.

Disclosures

The authors have no funding sources, disclosures, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- Onal H, Ersen A, Gemici H, et al. (2018) Acquired Chiari I malformation secondary to spontaneous intracranial hypotension syndrome and persistent hypoglycemia: A case report. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 10: 391-394.

- Schievink WI, Maya MM, Louy C, et al. (2013) Spontaneous intracranial hypotension in childhood and adolescence. J Peds 163: 504-510.

- Kranz PG, Gray L, Malinzak MD, et al. (2019) Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 29: 581-594.

- Chung SJ, Lee JH, Im JH, et al. (2005) Short- and long-term outcomes of spontaneous CSF hypovolemia. Eur Neurol 54: 63-67.

- Özge A, Bolay H (2014) Intracranial hypotension and hypertension in children and adolescents. Curr Pain Headache Rep 18: 430.

- Atkinson JLD, Weinshenker BG, Miller GM, et al. (1998) Acquired Chiari I malformation secondary to spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leakage and chronic intracranial hypotension syndrome in seven cases. J Neurosurg 88: 237-242.

- Kingston W, Hoxworth J, Halker-Singh R (2017) Spontaneous intracranial hypotension diagnosed as Chiari I malformation. Neurology 88: 1294.

- Puget S, Kondageski C, Wray A, et al. (2007) Chiari-like tonsillar herniation associated with intracranial hypotension in Marfan syndrome. Case report. J Neurosurg 106: 48-52.

- Schönberger J, Mölenbruch M, Seitz A, et al. (2017) Chiari-like displacement due to spontaneous intracranial hypotension in an adolescent: successful treatment by epidural blood patch. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 21: 678-681.

- Dias MS, Li V, Pollina J (1999) Low-pressure shunt ‘malfunction’ following lumbar puncture in children with shunted obstructive hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurosurg 30: 146-150.

- Wu JW, Hseu SS, Fuh JL, et al. (2017) Factors predicting response to the first epidural blood patch in spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Brain 140: 344-352.

- Alkan O, Yildirim T (2011) Pseudoarachnoiditis in spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Balkan Med J 28: 107-110.

Corresponding Author

Naina L. Gross, MD, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 1000 N. Lincoln Blvd., Suite 4000, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA

Copyright

© 2021 Carter LM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.