Intraoral Aggressive Fibromatosis: Current Management and Presentation of a Case

Abstract

Aggressive fibromatosis, also known as muscle-aponeurotic fibromatosis or desmoid tumour, is a benign neoplasm caused by a monoclonal proliferation of the muscle-aponeurotic structures. It is characterised by a slow proliferation of differentiated myofibroblasts with insignificant metastatic power, although they have a locally aggressive behaviour and a great tendency to relapse. The treatment of choice has varied in recent years, with surveillance currently being the first option to consider. New medical treatments have been described and there are studies underway, in which different drugs are compared in order to be added to the therapeutic arsenal against these tumours. The objective of this work is to do a bibliographic revision of this rare clinical entity and to present a clinical case of palatine muscle-aponeurotic fibromatosis, an unusual localisation of this tumour.

Keywords

Aggressive fibromatosis, Muscle-aponeurotic fibromatosis, Desmoid tumour, Palatal tumour

Case Presentation

We present a 23 year-old male, smoker, without other clinical background, remitted for an outpatient appointment because of a tumour in the left palate area, which has progressively grown. The patient did not refer pain nor bleeding.

In the physical examination we observed a 2 × 2 cm sessile mass in the left palate area, which bled through palpation and was painful during manipulation. Cervical exploration was normal. An excision-biopsy was performed, with the anatomopathological result of fibrous tissue with acute and chronic inflammatory phenomenon and reactive-looking vascular proliferation, without tumour proliferation in the remitted tissue. In the 3-month revision we observed a new growth of the lesion (Figure 1). Contrast CT-scan confirmed the existence of a left palatal lesion that reshaped the underlying bone. Gadolinium MRI described a voluminous solid tumour with homogeneous enhancement in the left anterolateral quadrant of the hard palate, eroding the underlying bone with altered signal, suggesting tumoral infiltration. Surgical intervention was decided in order to perform an exeresis of the tumoral mass with margins.

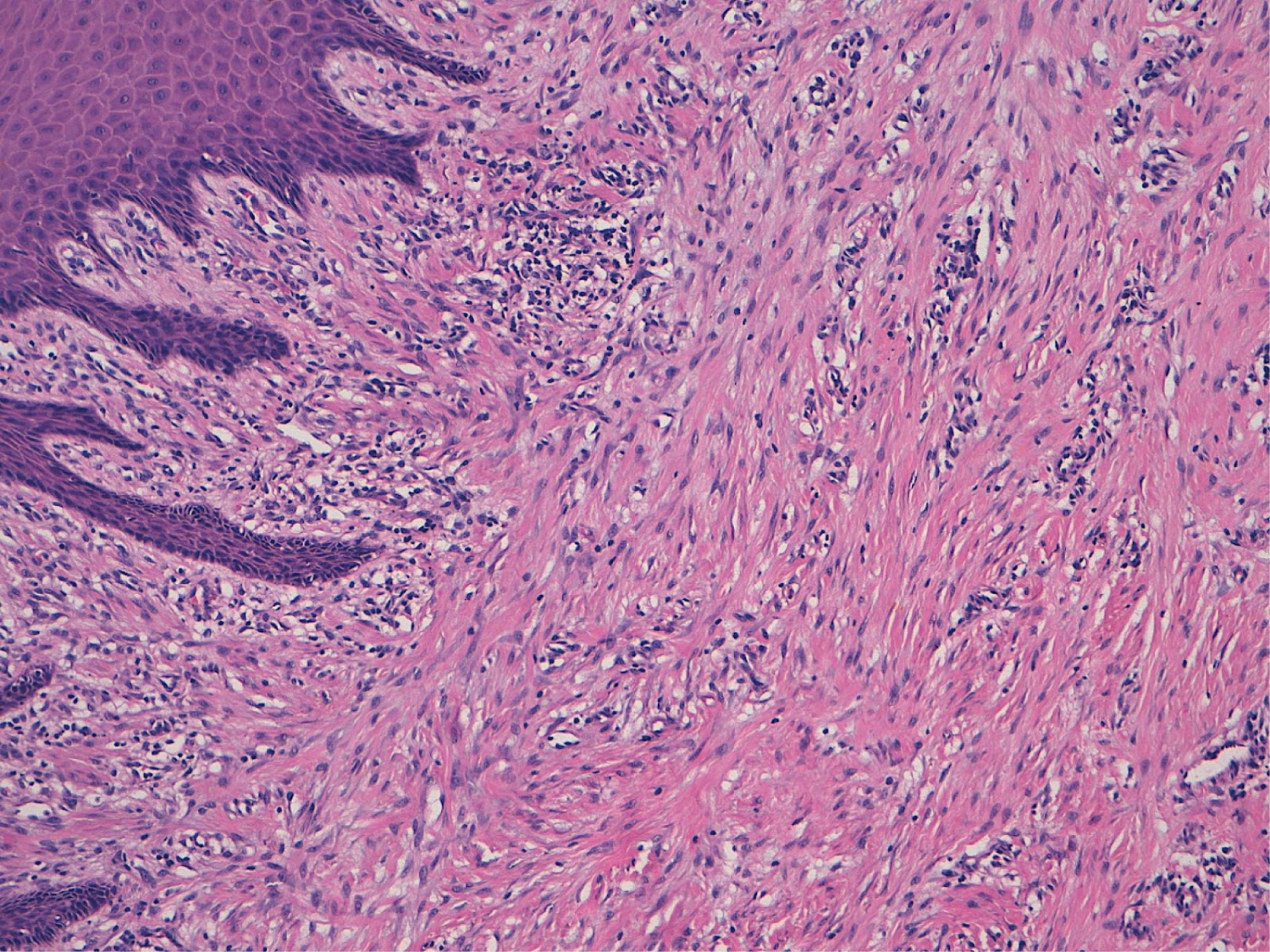

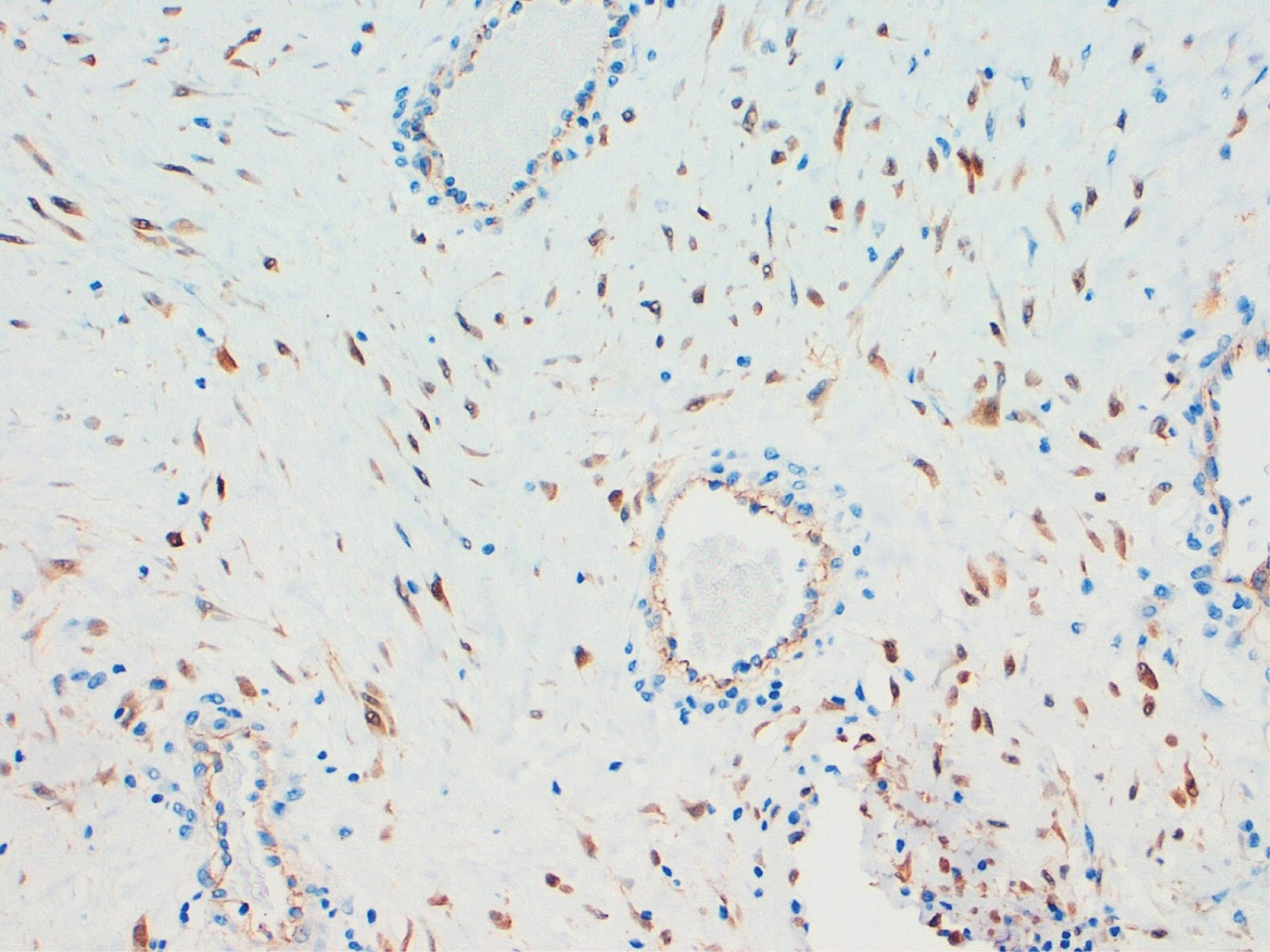

The pathological anatomy result of the sample was an intraoral muscle-aponeurotic fibromatosis that infiltrated the entire thickness of the specimen, with free edges (Figure 2). The immunohistochemical study was negative for actin, CD117 (c-kit) and S100 and positive for beta-catenin and vimentin (Figure 3).

The patient was discharged without incident, with good evolution in the successive controls (Figure 4), and without signs of locoregional recurrence in the long-term follow-up (10 years).

Discussion

Muscle-aponeurotic fibromatosis -also known as desmoid tumour- is a rare and benign entity, originally described in 1832 by McFarlane (Great Britain) as a fibroblast proliferation. These tumours present an infiltrative growth pattern, causing destruction of neighbouring tissues, and a marked tendency to recurrence. They differ from fibrosarcomas in their not metastatic capacity and their less cellularity, not presenting a pseudo-capsule and in their absence of abnormal mitoses [1,2].

They present an incidence of 2-4 cases per million inhabitants / year, being more frequent in women (ratio 3:1). Although they can occur at any age [3], they have two incidence peaks, one at 4-5 years old and another between 15 and 35 years old. Desmoid tumours typically appear in the postpartum period, in the anterior rectus muscle of the abdomen and in scars from previous surgeries, but they can appear in any muscle of the body, being also frequent in the limbs and the mesentery. Together they represent less than 3% of all fibromatous soft tissue neoplasms, and only 7-15% occur in the head and neck [4]. They are classified as sporadic or associated with hereditary syndromes; they can also be classified depending or their location, as superficial or deep tumours [3,5].

Cytogenetic studies have shown that there is an alteration of the Wnt/ β-catenin pathway in its pathogenesis. β-catenin is a cell adhesion molecule of the mesenchymal cells. Despite their benign histological appearance and insignificant metastatic potential, these cells cause significant local infiltration [2]. They also present a great tendency to recurrence, between 35 and 70% depending on the series [1,6]. The clinical presentation is highly variable: Most of them are presented as painless masses, but they can cause local complications such as intestinal obstruction, hydronephrosis or, exceptionally, intestinal perforation. In the case of head and neck tumours, they can cause trismus, airway obstruction, dysphagia, facial paralysis, ocular proptosis [5,7].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging test of choice for the diagnosis, local staging and follow-up of desmoid tumours. Hisopathological confirmation is mandatory before starting treatment, preferably with core needle biopsy. Rates of initially undiagnosed cases up to 30-40% have been described [8]. Desmoid tumours are positive for nuclear β-catenin, vimentin, cyclooxigenase 2, PDGFRb tyrosine kinase, and androgen and estrogen β-receptors. On the other hand, they are negative for desmin, S-100, h-caldesmon, CD34 and c-KIT [7].

The traditional treatment has been surgical. However, surgical resection of these tumours is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and it is currently not the treatment of choice [7,8]. In the European consensus in 2017 between SPAEN (Sarcoma PAtients EuroNet), EORTC (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer) and STBSG (Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group), an algorithm was developed that advocates conservative initial management (watchful waiting), since there are retrospective series that show a disease-free survival rate of 50% at 5 years in asymptomatic patients, and spontaneous regressions have been observed in 20-30% of cases [8]. Spontaneous regression is more likely in certain anatomical regions (e.g. abdominal wall): however, it has been described in all locations and it has also been described during menopause [1].

Treatment options include radiation therapy, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy. Radiation therapy plays an important role in the case of relapses, affected margins and as a first option to avoid mutilating resections. It achieves local control rates of approximately 75% to 80% [1,2]. Regarding hormonal therapy, cases of regression have been described with tamoxifen or oral contraceptives [1]. Chemotherapy can be used both in a low dose regimen with metrotrexate and/or vinblastine/vinorelbine and in a regimen based on anthracyclines. Chemotherapy is used in cases of symptomatic tumours, tumours located in a critical anatomical region or with aggressive growth, or after failure of hormonal therapy. The tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) imatinib, nilotinib, sorafenib, and pazopanib [9,10] have also been incorporated into the therapeutic arsenal.

In the case of head and neck desmoid tumours, the European consensus advises medical treatment as the first treatment option. However, in some conditions (elderly patients, intolerance to treatment or patient preference, comorbidities, rapidly growing lesions that threaten vital organs...) radiotherapy is preferred as the first line treatment. Surgery would be an option to consider initially in cases in which a resection with adequate margins can be achieved without causing functional or aesthetic sequelae. Given that the tumour lacks a capsule and the muscular extension is macroscopically imperceptible, it is advisable to resect all the involved tissue, associating radiotherapy to minimise the risk of local recurrence [9]. However, when the lesions include neurovascular structures or they are very extensive, many authors recommend combined treatment aimed at local control with preservation of function [11]. In the case of our patient, surgical resection achieved free margins, so the use of adjuvant therapy was rejected. No signs of recurrence have been observed during a long-term follow-up (10 years). Following the existing recommendations at that time, surgical management was decided as the first treatment option.

Conclusions

Aggressive fibromatosis is a disease with a variable and often unpredictable clinical course, characterised by an infiltrative growth with a tendency to local recurrence, but without metastatic capacity. Histopathological confirmation is necessary before deciding on treatment, and core needle biopsy is recommended. Although surveillance is currently recommended as initial management for these tumours, management must be individualised for each patient.

Funding

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

This work has previously been presented as a poster communication in a national congress (SECOM, Valladolid 2011, Spain).

References

- Dalit A, Karen M, Alexander M, et al. (2009) Congenital desmoid tumour of the cheek: A Clinicopathological case report. Eplasty 10: 52.

- Min R, Zun Z, Lizheng W, et al. (2011) Oral and maxillofacial desmoid-type fibromatosis in an eastern chinese population: A report of 20 cases. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology and Endodontology 111: 340-345.

- Moro A, De Angelis P, Gasparini G, et al. (2018) Orbital Desmoid-Type Fibromatosis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Oncol Med.

- Miyashita H, Asoda S, Soma T, et al. (2016) Desmoid-type fibromatosis of the head and neck in children: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 10: 173.

- Morillo MAC, Dieguez PRR, Navarro MAM, et al. (2012) Fibromatosis agresiva de cabeza y cuello en la edad pediátrica. Un caso clínico y revisión de la literatura. CIRUGÍA PEDIÁTRICA 25: 5.

- Suresh CS, Ali AA (2008) Desmoid tumour of the tongue. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 13: 761-764.

- Ganeshan D moorthy, Amini B, Nikolaidis P, et al. (2019) Current Update on Desmoid Fibromatosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 43: 29-38.

- Kasper B, Baumgarten C, Garcia J, et al. (2017) An update on the management of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis: A european consensus initiative between sarcoma patients euronet (spaen) and european organization for research and treatment of cancer (eortc)/soft tissue and bone sarcoma group. Ann Oncol 28: 2399-2408.

- Kasper B, Gruenwald V, Reichardt P, et al. (2017) Imatinib induces sustained progression arrest in RECIST progressive desmoid tumours: Final results of a phase II study of the German Interdisciplinary Sarcoma Group (GISG). European J Cancer. 76: 60-67.

- Gounder MM, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, et al. (2018) Sorafenib for Advanced and Refractory Desmoid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 379: 2417-2428.

- Collins BJ, Fischer AC, Tufaro AP. et al. (2005) Desmoid Tumors of the Head and Neck: A Review. Ann of Plastic Surgery. 54: 103-108.

Corresponding Author

Patricia de Leyva, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain, Tel: 660304983

Copyright

© 2021 Flores AMS, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.