Evaluation of Simulation Scenarios in a Bachelor´S Degree Programme in Nursing: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Objectives: The objective of this study was to describe the current state of scenario-based simulation (SBS) education in a Bachelor's Degree Programme in Nursing from the perspective of the quality of the scenarios.

Design: A descriptive, one-centre cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate the current quality and pedagogical usability of the written simulation scenarios. The scenarios were collected from professional study units included in the curriculum for a Bachelor's Degree Programme in Nursing.

Methods: An evaluation tool was designed based on previous literature and the standards set for the best practices for designing simulations. The data were analysed using Excel version 2010. The descriptive results are presented as total scores of the scenarios, categories, and statements and means and standard deviations.

Results: The written simulation scenarios were found to be of decent quality. Timetables were not documented for the simulation scenarios and debriefings were found to be lacking in quality. Greatest variation was found in the planning of how to run the simulations, e.g., giving participant's adequate cues for proceeding in the simulation.

Conclusion: The evaluation identified strengths and development areas in the promotion of SBSs in a Bachelor's Degree Programme in Nursing. While most objectives set for the scenario were of decent quality, the scenarios did not run smoothly. Helping teachers write better scenario scripts requires a common structure for the scripting process, which also serves as a checklist for providing all the necessary information on the scenario form.

Keywords

Quantitative analysis, Simulation scenario evaluation, Nurse education, Scenario-based simulation, Scenario development, Scenario scripting

Introduction

Scenario-based simulation (SBS) is an experiential learning method, in which students assess a patient, respond to a given situation, and evaluate potential outcomes. SBS includes a script prepared by the teacher depicting the clinical situation and context and emphasising both non-technical and technical learning objectives [1,2]. Such simulations promote healthcare students' in-depth learning by providing them with realistic opportunities for practising clinical skills and critical reasoning [3,4], communication and cooperation [5,6]. Simulations also build students' self-esteem and confidence and thus foster students' abilities to integrate theory into practice [3,7].

Careful scripting of the scenario helps to ensure that the simulation is consistent, standardised and offers all students similar learning opportunities. Additionally, the script makes it easier for teachers to run the simulation. Excessive variation in the planned psychomotor actions and dialogue can increase distractions, interfering with the understanding of the learning objectives and thus affecting the quality of the scenario [8].

Background

To use SBSs in a consistent manner, one needs to have a script of all the scenario phases including briefing, simulation action and debriefing [9]. Briefing is a phase that introduces students to the objectives set for the scenario and familiarises them with the environment in which the scenario takes place [10]. It helps students to understand the rationale for treatment or care widens their understanding of the upcoming situations and provides information about the content of the scenario [11]. The briefing also involves orientation with the used technology, equipment and both the opportunities and limitations of the scenario. Scripting of the briefing provides students with knowledge of the scenario and the roles and expectations of the actors and observers. Because students can find simulations intimidating and fear the subsequent criticism [12], producing materials that help students prepare for the situation, e.g., reading or written assignments or quizzes, prior to the simulation help students feel supported when they participate in simulations [9].

It is important for SBSs to have a script of learning objectives, which are based on an authentic patient situation and include a description of both technical and non-technical skills. Writing down the objectives needs to be based on defining the complexity level of the scenario e.g., comparing the objectives to the competence level of the students. [3,9]. When the objectives are sufficiently challenging, the scenario empowers students to expand their competence and thus deliver meaningful learning outcomes [3,13]. However, by eliminating any excessive elements of the scenario, in contrast with the often-complicated real-life situations, students should be helped to concentrate on learning only a few things in each scenario [14]. Additionally, the objectives must be clear, evaluable and focus on specific aspects avoiding overly broad perspectives [15]. Clear objectives are professionally written, realistic [11,12,16], and correspond with the learning objectives of the course and curriculum goals [3]. Explaining objectives carefully to the students helps create a shared understanding that promotes positive professional learning [17].

SBSs can be carried out using human patient simulators (HPSs) or standardised patients (SPs). Using HPSs enables practising the planning of nursing interventions realistically and concurrently and providing a real-time response for further interventions. SPs are appropriate in scenarios that require the patient to move and use gestures as part of the interaction [18,19]. The role of the SP and the cues used during the simulation need to be scripted in detail [20].

Learning in SBSs takes place either in actor or observer roles. The actors participate in the simulation in the professional roles assigned to them, which mimic their future occupation and the roles are described in the scenario script to give them instructions on how to act regarding their environment and limitations to reality. The observers make remarks about the scenario and prepare to comment in the debriefing [15,21]. The observers' tasks are scripted to help them focus on the objectives and to observe the flow of the scenario as if they were personally involved [22]. In a study by Cunningham and Cunningham [23], there was no difference in the learning outcomes of the students acting in the scenario and the ones observing it. Furthermore, tasks given to the observers have been found to support learning in accordance with the learning objectives [24].

During the simulation, the teacher can encourage students with convincing visual and auditory cues and cognitively help them make progress in the difficult situations of the scenario. Irrelevant or confusing information can also be incorporated into scenarios to make them more challenging for students [7,14]. Cues provide a positive framework for the progress of the scenario in response to students' actions and thus need to be written to remain standardized. Cues can show up, for example, as changes in vital signs on a monitor and providing new information about the patient's condition e.g., new laboratory results [14]. Moreover, planned time frames help the scenario proceed, ensuring that the required objectives are achieved in a reasonable time [16].

A structured debriefing has been argued to be the most important phase of the simulation because it promotes reflection by learning to self-correct and apply new and previous experiences in improving professional competence [6,25]. The debriefing usually include description, analysis, and application phases, which contain discussion of feelings and reactions evoked by the scenario, both positive choices made and ones which need further development, and a conclusion on how to transfer the gained knowledge to clinical practice (e.g., [11,26]).

During debriefing, students need to be prompted to further explain their experiences, unpack their emotions, or receive further feedback. As an ability to recognize and respond empathetically to the emotions of others is fundamental in nursing, debriefing provides an excellent opportunity to practice such skills [27]. It is particularly important to script at least the analysis phase because students need to be assisted to identify behaviours in the scenario that facilitated or impeded the clinical intervention and describe the thoughts behind their actions. Additionally, reflection needs to be connected to learning objectives and cover the affective, cognitive, and psychomotor domains of learning [5]. Using open-ended questions and getting feedback from the teacher and the co-learners helps students reflect on their strengths and weaknesses [3,7,16]. A well-scripted scaffolding approach, in which the teacher facilitates the reflection, solidifies the students' mental models and helps them connect the new learning content to future clinical experiences [26,28,29].

Designing SBS is time-consuming and requires simulation pedagogy competence, professional knowledge of the topic of the scenario [30] and understanding application of SBSs in practice [10]. Dileone, et al. [31] found that there is no consistency in how briefing should be best planned, and inconsistent design methods have been used in the past. There is also evidence of the need for a more standardized approach to the development of simulation scenarios [32,33]. The available frameworks for preparing faculty for simulation education fail to understand the currently common situation where a professional newcomer may have to "jump in" a new pedagogy without any guidance and enough time to prepare for the scenario script [34]. In response to the limited research in scripting simulation scenarios, this paper reports an evaluation of the scenario scripting in the field of healthcare in one Finnish university of applied sciences and identifies gaps in the proficiency of faculty to plan scenarios.

The purpose of the article is to describe the current state of scenario-based simulation education from the point of view of the quality of scenarios in nursing education. The aim of the study is to provide information on the strengths and development targets of simulation education to produce relevant simulation learning experiences and maintain a cost-efficient curriculum for simulation-based learning.

Methods

Study context

Savonia University of Applied Sciences (Savonia) established its Simulation Center and introduced simulation pedagogy in its curriculum in 2014. In the following years, teachers were trained on how to use SBS´s. The training included content about using scenarios in learning, technical and non-technical skills, the scenario development process, and the guided implementation of a scenario.

Savonia's teachers use a structured form for designing a scenario. The form helps teachers script the scenario and reminds them to plan all the important phases systematically (Figure 1). However, the form has not been developed since it was first introduced.

Research design and data collection

A descriptive, one-centre cross-sectional study was conducted on fall 2021 to evaluate the current quality and pedagogical usability of the written simulation scenarios in nursing education. The written scenarios were collected from professional study units in the nursing curriculum, which include simulations (N = 34, 1st to 6th semester, see Table 1) [35].

To evaluate the quality and pedagogical usability of the scenarios, an evaluation tool was designed by the researchers based on previous literature on simulation pedagogy [1,10,11] and the INCSAL standards for the best practices of designing, facilitating, and debriefing simulations [9,20,29,36]. The content validity of the tool was evaluated by four health care teachers who had expertise in simulation education. The clarity and relevance of each statement were commented on, further discussed, and revised when needed.

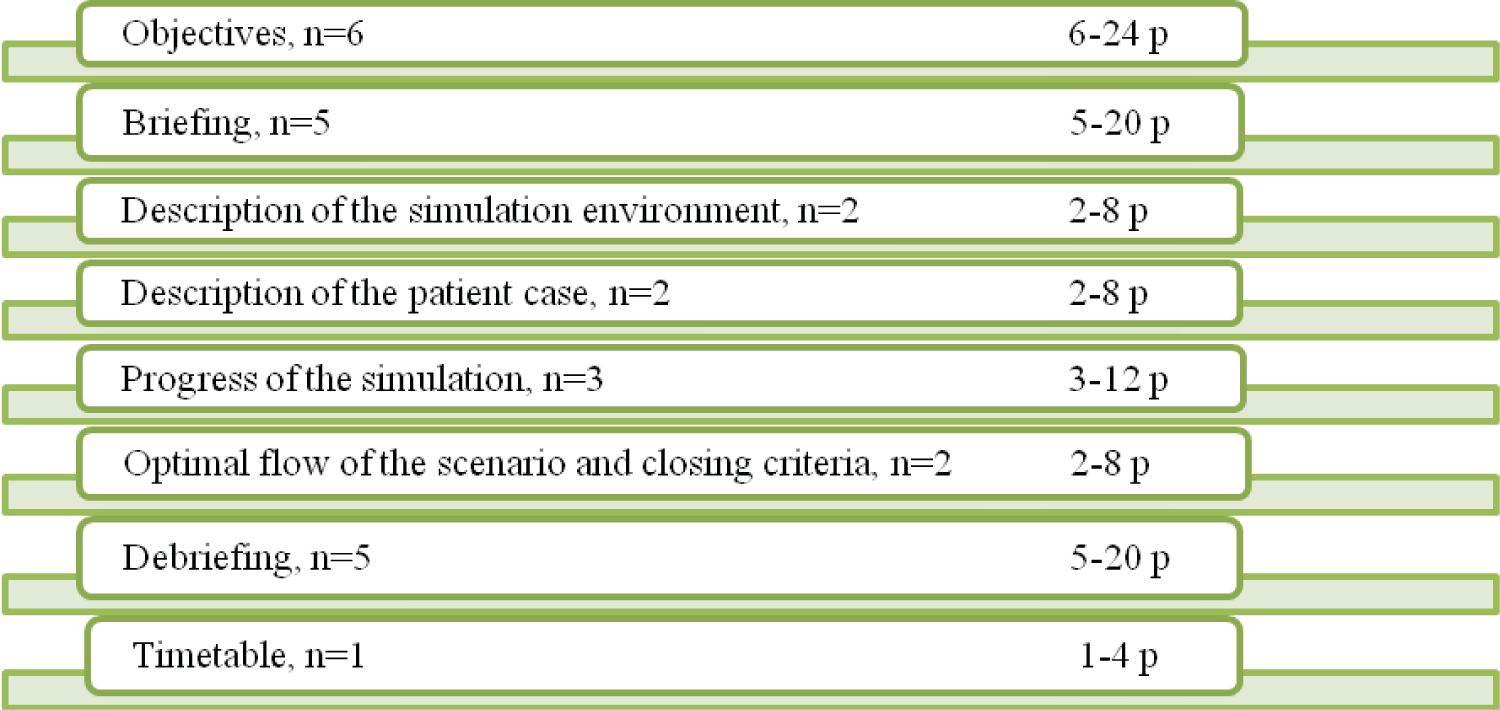

The final tool consisted of 26 statements grouped into 8 categories (Figure 2). The written simulation scenarios were carefully read and further evaluated according to the statements using a 4-step scale. The scale ranged from 1 "totally disagree or not possible to evaluate in this scenario" to 4 "completely agree". As a result, the minimum score for a simulation was 26 points and a maximum of 104 points.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using Excel version 2010. The descriptive results are presented as total scores of the scenarios, categories, and statements and means and standard deviations.

Ethical consideration

The data of this study consisted of written simulation scenario descriptions which are available for all the teachers working at the higher education institution in an online file. No personal data was included, and none of the teachers can be identified from the data. However, the researchers are aware that the evaluation of the simulation scenarios used in the Bachelor's Degree Programme in Nursing can potentially expose faculty to uncertainty [37]. Therefore, the results of the analysis were discussed constructively with the faculty and a plan was made to develop the scenario scripting. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the education organisation's ethical committee.

Results

The written simulation scenarios were found to be of decent quality. The total scores of the scenarios (N = 34) varied between 71 and 91 points out of 104 points (M = 82.1, SD = 4.2). Of the categories (Table 2), the patient case was consistently well described in the scenarios (M = 7.8 /8, SD = 0.6, range 6-8 p). Additionally, the simulation environment received mean points of 7.9/8 with greater variation in the quality (SD = 1.9, range 4-12 p). According to the results, the timetable was not documented at all in relation to written simulation scenarios. Debriefing was pointed out as lacking quality (M = 10.0 / 20 p, SD = 3.5, range 5 - 16 p).

On average, the reality (M = 3.9/4, SD = 0.7) and measurability (M = 3.9/4, SD = 0.4) of the scenario objectives and the learning objectives support students in reaching the learning objectives set for the study unit (M = 4.0/4, SD = 0.0) were found excellent (see Table 3). Additionally, excellent quality was addressed in the briefing regarding relevant study material used to promote preparing for the simulation (M = 3.9/4, SD = 0.5) as well as description of the roles played by the actors (M = 3.9/4, SD = 0.3). The context of the simulation scenario (M = 3.9/4, SD = 0.2) was described in high quality and included aspects fostering the realism of the scenario (M = 3.4/4, SD = 1.0). The patient's background information (M = 3.9/4, SD = 0.3) as well as the patient's current condition (M = 3.9/4, SD = 0.3) were described excellently in the scenarios.

The scenarios varied in how they planned for the patient's condition to change, requiring decision-making from the students (M = 2.5/4, SD = 1.3) and related information such as the patient's laboratory tests or functional capacity (M = 2.8/4, SD = 1.1). Some scenarios also lacked planned cues (M = 2.5/4, SD = 1.2).

Closing criteria to the scenario were professionally written for the scripts (M = 3.5/4, SD = 0.9). However, the evidence-based background of the scenario was found to be inadequate in many cases (M =2.3/4, SD = 1.5). Incomplete debriefing plans (M = 2.6/4, SD 1.3) and a lack of open-ended debriefing questions (M = 2.2/4, SD 1.2) were addressed as the poorest quality.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that the written scenarios of clinical situations and context were of high quality, emphasizing both non-technical and clinical learning objectives. The simulation objectives were realistic, and measurable and in line with Bambini's [1] and Hoffman, et al. [2] descriptions of good simulation objectives. These results are consistent with earlier studies [3,4], showing that well-scripted learning objectives support health care students' in-depth learning.

The quality of the briefing was described as excellent because of the relevant study material provided to the students prior to the simulation and as the roles of the actors and observers had been described clearly. Further, the study showed that the patient case, the description of the environment and the context of the scenario were logically connected with the learning objectives. Well-described observer tasks help the students focus on the objectives, motivating them to observe the scenario and reflect on their learning outcomes [22,24,27].

The simulation environment and the patient background information were well-scripted. However, the results showed variability in the patient clinical information and changes in patients´ condition, which is a significant area for future development. Detailed descriptions of sufficient patient information help in designing realistic scenarios. Earlier studies show that realistic simulations help students solve problems and make decisions during simulations [3,12] and support transferring learning outcomes from simulation to clinical practice [7,16].

The findings of this study indicate that there is a general lack of preparing cues even though these are important for both supporting students' progress and including positive challenges in the scenario. Concise scripted explanations of cues help teachers in providing context for the simulation activities [38]. Therefore, well-planned written cues on the simulation scenarios standardize the simulation education and minimize variation in the course of events in the scenario caused by the teacher.

This study found that the debriefing was not systematically based on any debriefing models such as Zigmont et al. [39] or Phrampus and O'Donnell [40], to ensure that the simulation comprises appropriate and structured reflection. The analysis and reflection of the actions performed during the debriefing should broaden students' understanding of the scenario emotionally, ethically and practically, and thus help them recognise how their knowledge on the subject has, or needs to be, changed [41]. Therefore, the teacher must plan stages of the debriefing that include summarising the simulation to ensure that students get an opportunity to reflect on the most important learning outcomes [42]. Additionally, the written scenario should include instructions for supporting the psychological safety of the actors and observers because safety has been found to increase students' ability to take sufficient interpersonal risks [17].

The results of this study revealed that timetables were not documented for the written scenarios. This finding demands urgent development of the currently used scenario form and made to include the duration of the briefing, simulation action and debriefing. The lack of a schedule decided in advance led to increased variation in the implementation of the scenarios, which weakened the quality of the simulations. As a result, the students may not have had enough time to act or the debriefing has been too long. Simulation scenario scripts with suitable time allocation support teachers in guiding simulations by ensuring a reasonable timeframe for achieving the desired outcomes [1,16,43].

This study involved evaluating all simulation scenarios for the Bachelor's Degree Programme in Nursing, providing a comprehensive understanding of the quality of the scenarios used in nursing education. This is the first time for assessing a Finnish Nursing education from the point of view of simulation scenario quality. This has considerable potential for fostering educational dimensions and nursing students' competence. The evaluation tool is based on an international framework and characteristics of designing simulation scenarios and helps to ensure systematic and criteria-based evaluation. Furthermore, the tool is easy to use and does not require significant training, or the investment of time or resources in the assessment.

Limitations

This study was carried out in a single university. Therefore, the results cannot be more widely generalized. To improve the external validity of this study, it would be important to carry out a similar study in other universities and in other educational programs. However, this poor generalizability may be mitigated by the fact that the sample included all the simulation scenarios carried out in the Bachelor's Degree Programme in Nursing, which creates a representative view of one degree programme. This study also focused specifically on the evaluation of the quality of simulation scenarios by three researchers without a blind evaluation process. Therefore, their subjective opinions might have affected the evaluation of a given simulation scenario. However, the researchers discussed the principles of evaluation and, in case of uncertainty in the evaluation, further discussed the matter.

Conclusions

Carefully designing simulation scenarios fosters the quality and standardization of simulation education, but there is a need to offer teachers more practical tools and advice for scenario development. This study helps to target resources to the core competencies of the education and shows that the scenario evaluation helps to identify strengths and development dimensions in the SBSs in nursing education. Most scenario objectives were of decent quality and enabled evaluating students' learning outcomes. However, the scenarios were not run well, providing insufficient cues, which emphasised the need for more details of the changes in the patient's condition to facilitate practising nursing skills. Additionally, the debriefing should be planned carefully to maintain comprehensive learning experiences, which support students' reflection and ensure a high-quality debriefing. Moreover, helping teachers write better scenario scripts requires introducing an updated and common structure for the scripting process, which also serves as a checklist for providing all the necessary information on the scenario form. Future research is required to develop guidelines for the preparation of debriefings and planning the progress of the scenario.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations of Interest

None.

Author Contributions

Marja Silen-Lipponen, Marja Aijo and Suvi Aura Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing original draft, reviewing and editing, Visualization. Marja Silen-Lipponen and Suvi Aura development of the simulation scenario evaluation tool.

References

- Bambini D (2016) Writing a simulation scenario: a step-by-step guide. Adv Crit Care 27: 62-70.

- Hofmann R, Curran S, Dickens S (2021) Models and measures of learning outcomes for non-technical skills in simulation-based medical education: Findings from an integrated scoping review of research and content analysis of curricular learning objectives. Stud Educ Eval 71: 101093.

- Li Z, Huang FH, Chen S-L, et al. (2021) The learning effectiveness of high-fidelity simulation teaching among Chinese nursing students: A mixed-methods study. The J Nurs Res 29: 1-10.

- Sullivan N, Swoboda SM, Breymier T, et al. (2019) Emerging evidence toward a 2:1 clinical to simulation ratio: A study comparing the traditional clinical and simulation settings. Clin Sim Nurs.30: 34-41.

- Holtscneider M, Park C (2019) Simulation and advanced practice registered nurses: Opportunities to enhance interprofessional collaboration. Adv Crit Care 30: 269-273.

- Stanley K, Stanley D (2019) The HEIPS framework: Scaffolding interprofessional education starts with health professional educators. Nurse Educ Pract 34: 63-71.

- Hustad J, Johannesen B, Fossum M, et al. (2019) Nursing students’ transfer of learning outcomes from simulation-based training to clinical practice: A focus-group study. BMC Nursing 18: 1-8.

- Rutherford-Hemming T (2015) Determining content validity and reporting a content validity index for simulation scenarios. Nurs Educ Perspect 36: 389-393.

- INACSL Standards Committee, Watts P, McDermott D, et al. (2021) INASCL Standards of Best PracticeTM Simulation Design. Clin Sim Nurs 58: 14-21.

- Chamberlain J (2015) Prebriefing in nursing simulation: A concept analysis using Rodger’s methodology. Clin Sim Nurs 11: 318-322.

- Husebo S, Dieckmann P, Rystedt H, et al. (2013) The relationship between facilitators' questions and the level of reflection in postsimulation debriefing. Simul Healthc 8: 135-142.

- Raewyn L, Daniel B, Harland T (2021) Learning with simulation: The experience of nursing students. Clin Sim Nurs 56: 57-65.

- Bland A, Tobbell J (2016) Towards an understanding of the attributes of simulation that enables learning in undergraduate nurse education: A grounded Theory study. J Nurs Educ 44: 8-13.

- Dieckmann P, Krage R (2013) Simulation and psychology; creating, recognizing, and using learning opportunities. Curr Opinion Anaesthesio 26: 714-720.

- McGaghie W, Issenberg S, Barsuk J, et al. (2014) A critical review of simulation-based Mastery learning with translational outcomes. Med Educ 48: 375-385.

- Arrogante O, González-Romero GM, Carrión-Garcia L, et al. (2021) Reversible causes of cardiac arrest: Nursing competency acquisition and clinical simulation satisfaction in undergraduate nursing students. Int Emerg Nurs 54: 1-7.

- Rudolph J, Reamer D, Simon R (2014) Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation. The role of the presimulation briefing. Simul Healthc 9: 339-349.

- Rutherford-Hemming T, Alfes CM, Breymier T (2019) A systematic review of the use of standardized patients as a simulation modality in nursing education. Nurs Educ Perspect 40: 84-90.

- Slater L, Bryant K, Ng V (2016) Nursing student perceptions of standardized patient use in health assessment. Clin Sim Nurs 12: 368-376.

- INACSL Standards Committee (2016) INACSL standards of best practice: SimulationSM Clin Sim Nurs 12: S16-S20.

- Silén-Lipponen M, Saaranen T (2021) Reflection as a factor promoting learning interprofessional collaboration in a large-group simulation in social and health care. International Journal of Nursing and Health Care Research 4: 1241.

- Verkuyl M, Atack L, McCulloch T, et al. (2018) Comparison of debriefing methods following a virtual simulation: An experiment. Clin Simul Nurs 19: 1-7.

- Cunningham S, Cunningham C (2019) Optimizing the observer experience in an interprofessional home health simulation: A quasi-experimental study. J Interprof Care 6: 1-4.

- Nyström S, Dahlberg J, Hult H, et al. (2016) Observing of interprofessional collaboration in simulation: A socio-material approach. J Interprof Care 30: 710-716.

- Lavoie P, Pepin J, Cossette S (2015) Development of a post-simulation debriefing intervention to prepare nurses and nursing students to care for deteriorating patients. Nurse Educ Pract 15: 181-191.

- Sawyer T, Eppich W, Brett-Fleegler M, et al. (2016) More than one way to debrief: A critical review of healthcare simulation debriefing methods. Simul Healthc 11: 209-217.

- White H, Hayes C, Axisa C, et al. (2021) On the other side of simulation: Evaluating faculty debriefing styles. Clin Sim Nurs 61: 96-106.

- Cantey DS, Randolph SD, Molloy MA, et al. (2017) Student-developed simulations: Enhancing cultural awareness and understanding social determinants of health. J Nurs Educ 56: 243-246.

- INACSL Standards Committee (2016) INACSL standards of best practice: SimulationSM Clin Sim Nurs 12: S21-25.

- Maloney S, Haynes T (2016) Issues of cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness for simulation in health professions education. Adv Simul 1.

- Dileone C, Chyun D, Diaz D, et al. (2020) An examination of simulation prebriefing in nursing education: An integrative review. Nurs Educ Perspect 41: 345-348.

- Bodak M, Harrison H, Lindsay D, et al. (2019) The experiences of sessional staff teaching into undergraduate nursing programms in Australia: A literature review. Collegian 26: 212-221.

- Hitch D, Mahoney P, Macfarlane S (2017) Professional development for sessional staff in higher education: A review of current evidence. High Educ Res Dev 37: 285-300.

- Cheng A, Grant V, Robinson T, et al. (2016) The promoting excellence and reflective learning in simulation (PEARLS) approach to health care debriefing: A faculty development guide. Clin Sim Nurs 12: 419-428.

- Polit DF, Beck CT (2018) Essentials of nursing research. Appraising evidence for nursing practice, (9th edn), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- INACSL Standards Committee (2017) INASCL standards of best practice: SimulationSM: Operations. Clin Sim Nurs 13: 681-687.

- Blondy LC (2011) Measurement and comparison of nursing faculty members’ critical thinking skills. West J Nurs Res 33: 180-195.

- Spruit EN, Band GP, Hamming JF, et al. (2014) Optimal training design for procedural motor skills: A review and application to laparoscopic surgery. Psychol Res 78: 878-891.

- Zigmont JJ, Kappus LJ, Sudikoff SN (2011) The 3D model of debriefing: Defusing, discovering, and deepening. Semin Perinatol 35: 52-58.

- Phrampus P, O’Donnell J (2013) Debriefing using a structured and supported approach. In: Levine A, DeMaria S, Schwartz A, Sim A, The Comprehensive Textbook of Healthcare Simulation. (1st edn), Springer, New York, NY, 73Y85.

- Kim YJ, Yoo JH (2020) The utilization of debriefing for simulation in healthcare: A literature review. Nurse Educ Pract 43: 102698.

- Eppich WJ, Hart D, Huffman JL (2021) Debriefing in emergency medicine. In: Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Emergency Medicine. Springer, Cham, 33-46.

- Mascarenhas S, Al-Halabi M, Otaki F, et al. (2021) Simulation-based education for selected communication skills: Exploring the perception of post-graduate dental students. Korean J Med Educ 33: 11-25.

Corresponding Author

Marja Silen-Lipponen, PhD, RN, Principal Lecturer, Savonia University of Applied Sciences, Unit of Health Care, FI-70201 Kuopio, Finland, Tel: +358 44 785 6489

Copyright

© 2022 Silen-Lipponen M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.