Caring for People with Alzheimer's Disease Who Show Defensive Behaviours: Part 1: Four Essential Pieces of Nursing Knowledge

Abstract

When caring for people living with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and showing aggressive behaviours, nurses must perform a knowledge-based nursing practice to better understand the people's needs and support them. This article aims to present a structure for the knowledge essential for nurses caring for people living with Alzheimer's disease who show defensive behaviours. People living with AD some times show defensive behaviours that have disastrous consequences for them, their family members, the other residents, and the formal caregivers. Rather than considering these behaviours as being aggressive and disruptive, nurses must understand that they are protective and defensive. Because of the important role that nurses have in the care of people living with AD, they must possess specific knowledge. This discursive paper is based on the literature of defensive behaviours and integrates the Fundamentals of Care Framework. We use Kim's perspective regarding the knowledge-based practice and the knowledge-use in nursing practice. Several dimensions that must be considered for the nursing practice for the elderly living with AD are introduced. This permits to present a clinical gerontological nursing process centred on the relationship with the person living with AD and their family. Moreover, a mid-paradigm for nursing care of these people is introduced. Then, essential nursing knowledge for the care of people living with AD is presented in four parts, which are 1) Characteristics of AD, 2) Goals of the behaviours, 3) Contributing factors, and 4) Ecobiopsychosocial and pharmacological interventions related to the person and family's needs. The specific structure of knowledge permits to precisely identify pieces of knowledge nurses should possess and nursing students should learn in order to take care of people living with AD and their families.

Keywords

Dementia care, Fundamental care, Nursing theory, Family-Centred care, Aggression management, Non-Pharmacological method

List of Abbreviations

AD: Alzheimer's disease, FOC: Fundamentals of Care

Aim

This article aims to present a structure for the knowledge essential for nurses and nursing students caring for people living with Alzheimer's disease who show defensive behaviours.

Background

People living with Alzheimer's disease (AD) sometimes show intriguing behaviours that family members and caregivers have difficulty understanding. These behaviours are often called behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. However, instead of seeing all behaviours shown by people with AD as symptoms of the disease, it is very important to consider most of their behaviours as a legitimate response to stimuli [1,2]. That is why some authors would rather call them responsive behaviours [3,4].

Under certain circumstances, responsive behaviours may have a verbally or physically aggressive tone. It is complicated to present the prevalence of aggressive behaviours shown by people living with AD because these behaviours are most often mixed with agitation behaviours [5], which is unsatisfactory [6-8]. Despite this, some authors state that 25 to 50% of people living with AD will show aggressive behaviours during the course of their disease [9-14]. With agitation, aggressive behaviours are described as being the most frequent behaviours shown during a behavioural crisis by people living with AD [15]. Regarding residents in nursing homes, some authors assert that the prevalence of aggressive behaviours can be as high as 84% [16,17]. These various results demonstrate that aggressive behaviours shown by people living with AD are a relatively frequent phenomenon in different health institutions.

Relational, Protective, and Defensive Behaviours

Some authors explain that aggressive behaviours may be reactive, as an answer to a perceived threat, or proactive, as a planned behaviour anticipating a reward [7,18,19]. Because of the effects of Alzheimer's disease on cognitive and executive functions, people living with AD rarely show proactive aggressive behaviours [8]. Therefore, for this article, and considering their context of emergence and their purpose, aggressive behaviours are understood in two ways: 1) As relational behaviours, and 2) As protective and defensive behaviours. The aggressive behaviours are relational because they always occur during an interaction between a person living with AD and another person acting as a formal carer, a family member, another resident, a visitor, or even an object. From another point of view, the aggressive behaviours are protective and defensive. Indeed, these behaviours are the way the person living with AD tries to communicate compromised needs (e.g. hunger, thirst, pain) or attempts to protect and defend her or himself against something perceived as threatening and potentially dangerous [7,8,20,21,22]. For this article and for the sake of simplicity, relational behaviours as well as protective and defensive behaviours shown by people living with AD will be generally called "defensive behaviours".

Unfortunately, the defensive behaviours are often misunderstood by family, formal caregivers, and nursing students, and are interpreted as dangerous and disruptive behaviours solely caused by the AD. Consequently, restraint and isolation measures are sometimes used. For example, chemical restraint could be used to reduce the frequency and intensity of defensive behaviours [23]. Additionally, physical restraint or isolation could be used to limit the impact of those defensive behaviours. In most cases, these measures do not target the causes of the behaviours and can even have a devastating impact on people with AD's health, well-being, and quality of life.

Obviously, the defensive behaviours shown by people living with AD may also have disastrous consequences for other people, such as fear and injuries. In nursing homes, formal caregivers are the first people to experience such bad consequences. For example, aggressive behaviours play an important role in stress and in both the subjective and objective nursing burdens [24]. When facing aggressive behaviours, formal caregivers may feel exhausted, resigned, hopeless, incompetent, and unable to perform the care tasks [12,25]. The most frequent victims of these physically aggressive behaviours are professional carers and other patients. The results of a Swiss study demonstrate that among 3919 formal caregivers of 155 nursing homes [26], 2584 (66%) reported verbally aggressive behaviours, 1629 (42%) physical ones, and 600 (15%) sexual ones. A study in a geriatric psychiatry unit demonstrates that 82% of the aggressive incidents observed were directed at nurses, regardless of whether they were women or men [14]. Somehow, family members and people who are unknown to the person living with AD are also affected by these behaviours [13]. It is important to note that aggressive events may also occur between residents and may have disastrous consequences [27-29].

Thus, it is important for carers who care for people living with AD who show responsive behaviours, sometimes called behavioural symptoms of dementia, to understand that these behaviours are linked to some contributing factors, to thoroughly identify these factors, and to intervene on them [20,23,30-32]. Now, since nurses working in nursing homes must be able to assess the person's needs and determine judicious interventions, they have an essential contribution to make. However, since these situations are extremely complex and relational, nurses must be guided to be able to carry out a complete and relevant clinical process.

Discursive Paper

This discursive paper is intended to propose a structure for the knowledge required by all nurses and nursing students who care for people living with AD and showing defensive behaviours regardless of practice areas or clinical settings. This paper is for nurse educators, internship supervisors, counsellors, or managers, as well as nursing students.

Because of the extent of this work, we publish it in two distinct and complementary parts. The first part presents a structure of four essential pieces of nursing knowledge for the care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours. The second part will present a situation-specific version of the Fundamentals of Care Practice Process centred on people living with AD who show defensive behaviours. In part two, a clinical scenario will illustrate the relevance of using this adapted version of the Fundamentals of Care Practice Process.

First, Kim's perspective of knowledge-based and knowledge-use nursing practice will be introduced. This will allow the essential tools of nursing practice and clinical process to be presented and to explain our starting point. Moreover, we will be able to present our proposal about nursing care of people living with AD and showing defensive behaviours from a mid-paradigmatic perspective. Second, the four essential pieces of nursing knowledge for the care of people showing defensive behaviours will be presented. Finally, following a brief conclusion, the relevance of our proposal to clinical practice will be described. The practice process of our proposal will be presented in the second part of the article.

Knowledge-Based Nursing Practice and Knowledge-Use in Nursing Practice

For this paper, Kim's perspective [33,34] regarding the knowledge-based practice and the knowledge-use in nursing practice will be used. This choice is linked to Kim's normative model for nursing practice "...specifying how and what nursing practice ought to be, rather than what it is" [34].

To begin, the perspective of knowledge-based nursing will be briefly presented. Next, some explanations about the processes of knowledge synthesis and use in practice will be given. Once these foundations have been introduced, the knowledge-based practice for people living with AD who show defensive behaviours will be presented through two levels of knowledge, namely, general, and situation-specific.

Knowledge-based nursing

For Kim [34], knowledge-based nursing practice integrates the content and process. The content refers to the necessary knowledge that should guide a nursing practice. The process refers to the use of this knowledge in practice. The knowledge used in nursing practice is related to theory, not just to evidence from research [33,34].

For Kim [34], each discipline has its own public knowledge that needs to be synthesized into private knowledge that nurses can use in practice. Therefore, a three-step process of knowledge synthesis must be done. The knowledge synthesis is carried out based on knowledge from the public and private domains. The public domain knowledge is related to theory development, research, consensus development, standards formulation, and maxims and models [34]. The private domain knowledge is related to personal clinical experiences [34]. The first step of the knowledge synthesis process is the selection of new knowledge by the nurse. This selection process is linked to knowledge readiness. The second step is a critical assessment process. The nurse discriminates between knowledge available. This step is influenced by analytical skills, personal knowledge, and supporting mechanisms (scientific journals, programs, etc.) related to the facts that the nurse believes that the knowledge is "valuable, essential, meaningful, and important for practice" [34]. This critical assessment process is linked to the value of the knowledge. The third step represents the integration of public knowledge with knowledge coming from each nurse's personal clinical experience to create the personal knowledge used in practice. This step refers to the reflexive attitude of the nurse. The nurse takes a conscious position. This integration process is linked to the relevance, utility, and fittingness of the knowledge.

Furthermore, based on Kim's proposal for knowledge-based nursing practice [33,34], we affirm that nurses must have access to public knowledge which is essential to care for individuals with AD who show defensive behaviours. That is why we will present a summary of the public domain knowledge on the subject of defensive behaviours, as well as that of the practice process which helps nurses to synthesise it as private knowledge with the aim of using it in their practice.

Now that the knowledge-based nursing has been presented, the knowledge-based practice for people living with AD who show defensive behaviours can be described.

Knowledge-based practice for people living with Alzheimer's showing defensive behaviours

The use of theories in clinical nursing practice is presented based on two different roles of theory [33]. The first role of theories is "...to formulate orientations, attitudes, and commitments to the fundamental features of nursing practice" [33]. This foundational role of knowledge refers to the first level and is related to the general and un-specified role of nursing. The second way to use theories in nursing practice is related to a selective choice of theories "...to address each clinical situation to understand and explain it, to arrive at nursing approaches responding to the requirements of the clinical situation, and to carry out nursing care" [33]. This instrumental role of knowledge refers to the second level and is related to the particularistic and situation-specific role of nursing.

To identify the content of the needed theoretical knowledge base, we searched for and gathered a body of data from our clinical, academic, and research activities. We also conducted a research of theoretical and empirical data on databases (CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO, Ageline, Web of Science). After having reviewed each piece of data, we gathered topics and created different categories of knowledge. Our approach was iterative and required both inductive and deductive processes of thinking.

The main components of each of the two roles of theories for nursing practice with people living with AD who show defensive behaviours are presented below.

General level of knowledge for elderly nursing practice

At a general level of knowledge, we can find some propositions about the knowledge that nurses caring for the elderly should possess. Some of these propositions have been considered below in order to build our proposal.

Since we are speaking of nursing practice, it is important to view the knowledge from a nursing perspective. For this, we can use the well-known nursing metaparadigm formed using the concepts of human being, health, environment, and nursing [35]. When speaking of the concept of a human being, we must consider person-centred care [36-38]. Formal caregivers need to be informed about person-centred perspectives to be able to implement helpful strategies to prevent defensive behaviours or manage them as gently as possible [12,16]. Additionally, we must specify that it is not only the person living with AD, but also his or her family who must be considered [39-41]. That means that nursing care for people living with AD should be addressed from the perspective of family nursing [42]. Moreover, because of the relational context in which defensive behaviours occur, we also must consider purposefully the relationship-centred care proposals that are highly relevant for nursing and care for people living with AD [43-53]. The relationship-centred approach to care leads to "the development of meaningful relationships among persons living with dementia, their family partners in care, and the formal helping system" [54]. In fact, it is possible to say that the person and family dimensions are integrated into the relationship-centred perspective of care, since this one includes everyone involved in care, i.e., the resident, family members,and formal carers [55]. Thus, it is also possible to state that the Fundamentals of Care Framework is related to a relationship-centred care perspective as it shapes the dimensions of the person, family, formal carers, and their relationships [56,57].

Fundamentals of care framework

The Fundamentals of Care (FOC) Framework was developed using an inductive approach by International Learning Collaborative members in 2013 [58]. The FOC Framework has been modified over the years [56,59]. It provides nurses and other health professionals with a practical, evidence-based approach to addressing the Fundamental Care for people in care. The FOC Framework focuses on care activities that help meet people's fundamental needs and contribute to their well-being, health, recovery, and safety.

The FOC Framework is organized around three dimensions describing what a high-quality delivery of fundamental care means. The first dimension is the relationship established between the nurse and the person along with his or her family. This dimension is central to the FOC Framework and is a prerequisite to the other dimensions. The nurse's commitment to take care of the person is expressed through five elements, i.e., trust, focus, anticipate, know, and evaluate. The second dimension is the integration of care which relates to the person's physical, psychosocial, and relational needs. The third dimension is the context of care which relates to what is enabling the delivery of fundamental care. A practice process allowing the FOC Framework to be used in practice exists. This practice process will be presented in the second part of the article.

The general level of knowledge integrates nursing models. The Johnson's Model is very useful when considering defensive behaviours.

Nursing model: Johnson's behavioral system Model

Dorothy Johnson's Behavioral System Model appears to be particularly interesting for the phenomena of defensive behaviours. According to Johnson's theory, the individual is a behavioural system whose overall purpose is to maintain his or her integrity as a whole and to manage relationships with the environment [60]. Johnson's model comes in seven subsystems including an aggressive/protective subsytem. For Fawcett and De Santo-Madeya [35], the Behavioral System Model is located in the reciprocal interaction world view which is quite relevant for the article perspective.

For Johnson [60], behaviour is a set of actions and observable traits developed through maturation, experience, and learning. Behaviours are governed by physical, biological, psychological, and social factors [35,60]. The behavioural system is composed of seven distinct, open, and interrelated subsystems, including the aggressive-protective subsytem. With respect to the aggressive-protective subsystem, Johnson drew upon the ethological propositions of Lorenz and Feshbach, who conceive of this type of behaviour as being related to protection and survival [60]. The aggressive-protective subsystem will be one of the central concepts selected as a piece of essential nursing knowledge for the care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours.

Gerontological nursing knowledge

In this general level of knowledge, we have also retained other sources of reference and inspiration. For example, the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing [61] identifies three competencies for Bachelor's students. The first competency is to "collaborate with the older person and their family to promote health and well-being, foster resilience and adaptation to change, optimize function, and prevent illness and injury" [61]. This first competency presents 11 indicators including a therapeutic relationship with the older person and their family, collaborating with the older person, their family, and health care team to develop and implement a care plan, fostering positive and supportive relationships between the older person and others, and identifying actual or potential mistreatment/abuse to respond appropriately. The second competency is to "collaborate with the older person and family to optimize well-being in the context of complex health conditions which can be acute or chronic" [61]. This second competency also presents 11 indicators including conducting a holistic and comprehensive assessment, using critical thinking in monitoring, supporting older people and their family in navigating through transitions of care, and providing informational, emotional, and instrumental support to the family caregiver. The third competency is to "collaborate with the older person and family to provide competent, respectful, and culturally sensitive palliative and end-of-life care" [61]. This third competency presents eight indicators, including supporting older people in determining goals of care and advocating for the right to self-determination of care, including decision-making related to treatments.

Some years ago, the Canadian Gerontological Nursing Association [62] identified some competencies and practice standards for the nursing care of the elderly. These are organized into six categories which are related to physiological health, optimizing functional health, responsive care, relationship care, health system, and safety and security. Some years later, the Canadian Gerontological Nursing Association [63] presented their propositions in the following six categories: Relational care, ethical care, evidence-informed care, aesthetic and artful care, safe care, and socio-politically engaged care. These categories of knowledge can be very useful to consider from an organizational point of view, for example, in defining standards of practice for nurses working with the elderly and in describing job profiles.

Moreover, since 2010, the American Nurses Association has proposed six standards of practice for Gerontological Nursing [40], which are: 1) Assessment; 2) Diagnosis; 3) Outcome identification; 4) Planning; 5) Implementation, and 6) Evaluation. The fifth standard is divided into three parts as: 5a) Coordination of care, 5b) Health teaching and health promotion, and 5c) Consultation. These standards are related to the essential clinical steps that every nurse should take to assess an elderly person's health condition.

As we can see, the general level of knowledge for elderly nursing practice involves a variety of essential data related to nursing gerontological practice. These data permit understanding of the main principles guiding this practice. These general level components are useful in describing the gerontological nursing role and skills, and guide description of roles and deployment of nursing education. However, these general level data cannot be used directly in daily nursing practice and are not specific to the people living with AD who show defensive behaviours. Therefore, it is essential to care about guidelines and experts' recommendations.

Guidelines and experts' recommendations

Related to the care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours, we can also explore the guidelines related to reactive behaviours, or more broadly, to the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Many guidelines exist in many different countries [64-71]. Additionally, some experts' recommendations have been made concerning the clinical process and required steps which must be realizedwhen a person living with AD shows reactive behaviours. These experts' recommendations are often presented in an acronym or algorithm method [23,72-77] or in a multi-step process [31,78,79]. Some methods are more specifically proposed for reactive behaviours shown in the context of bodily care [80-84].

In summary, it is possible to recapitulate the main points of these guidelines and experts' recommendations in five stages. The description of the following stages is related to the nurse but, obviously, the interprofessional team is involved in each of them according to the person's needs. First, an in-depth assessment process must be realized. Second, this assessment process mainly serves to look for and find the factors contributing to the expression of defensive behaviours. Because these factors are related to the person, other people, and the environment, the assessment process must consider all three of them. Third, interventions must target the contributing factors. Nonpharmacological interventions are the first choice, and as they address the person, other people, and the environment, these interventions are ecobiopsychosocial [23]. Pharmacological interventions also target contributing factors such as pain, infection, or depression. Restraining measures are used as a last resort when ecobiopsychosocial interventions do not produce sufficient results. Such measures may also be used in situations of danger to the person or others, or in the case of severe psychological distress. Fourth, the interventions have to be put into practice carefully by the formal carers and family members. Finally, the intervention effects and results are measured and described.

Nursing gerontological clinical process

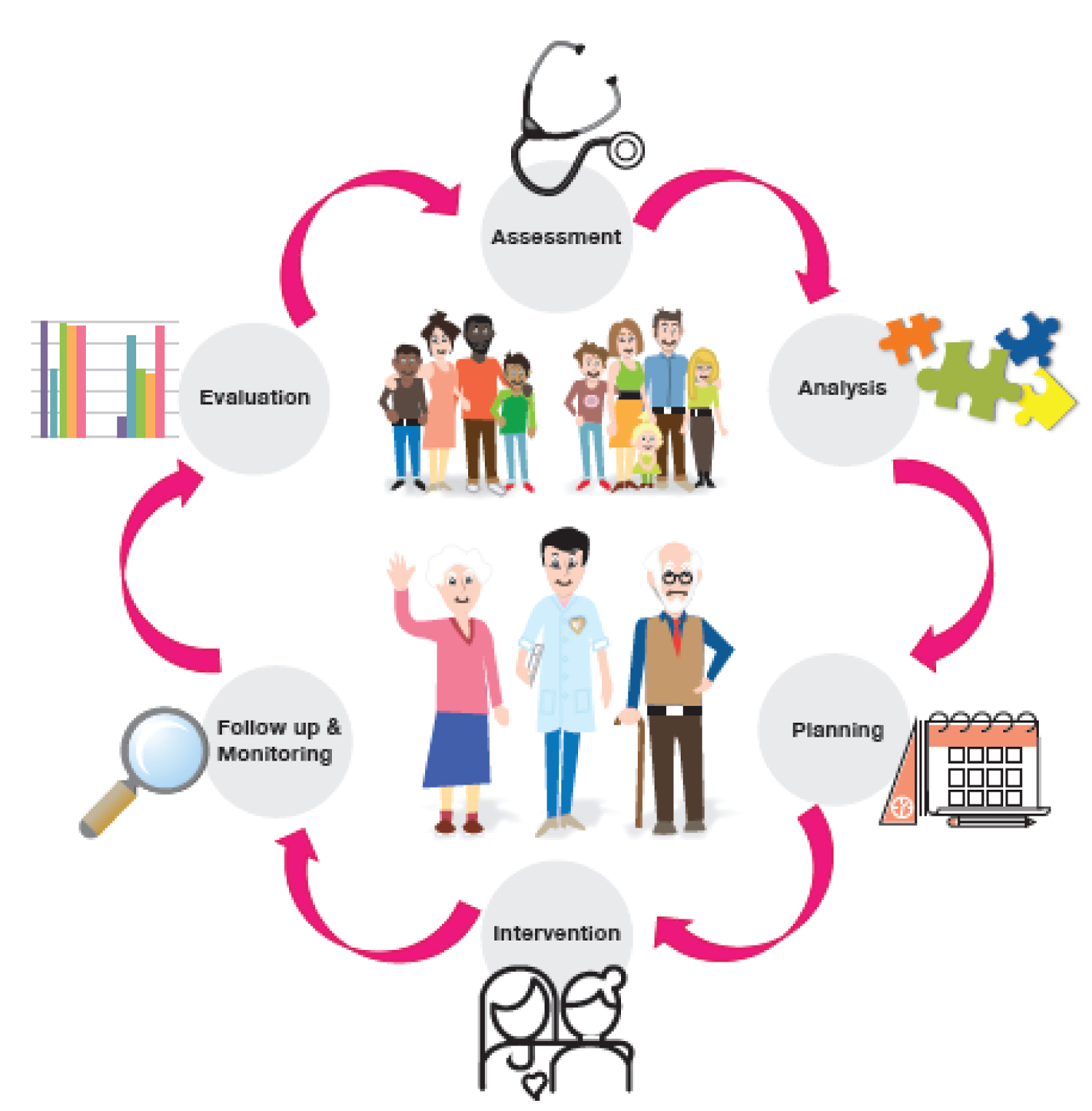

To close the point of knowledge-based nursing practice for people living with AD who show defensive behaviours, we recommend the nursing gerontological clinical process be carried out by nurses caring for these people and their families. Based on the aforementioned general level of knowledge data, we identify six components for the nursing gerontological clinical process (Figure 1). Inspired by the relationship-centred care perspective as well as related to the specific needs of family members of those living with AD [85,86], and because of the family's desire to be involved in the life and care of their parent and partner with the formal carers [41,87-90], we decided to carefully integrate the family dimension into our work.

After having considered these general level pieces of knowledge, we have worked on the second level of knowledge, i.e., situation-specific knowledge [33].

Situation-specific level of knowledge for nursing care of people living with Alzheimer's who show defensive behaviours

From a knowledge-used-in-practice perspective and based on the particularistic and situation-specific standpoint, we can state that nursing theories guide nursing actions [33]. The nursing care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours relates to multiple and complex data and theories. For now, four essential pieces of nursing knowledge have been identified.

The first essential piece of nursing knowledge allows the characteristics and impact of Alzheimer's disease to be described. The second essential piece of nursing knowledge is related to the understanding of defensive behaviours goals and utility. The third essential piece of nursing knowledge is centred on the causes of defensive behaviours, i.e., the factors contributing to the expression of these behaviours. Finally, the fourth essential piece of nursing knowledge is related to interventions that nurses can implement. These interventions are ecobiopsychosocial, and pharmacological.

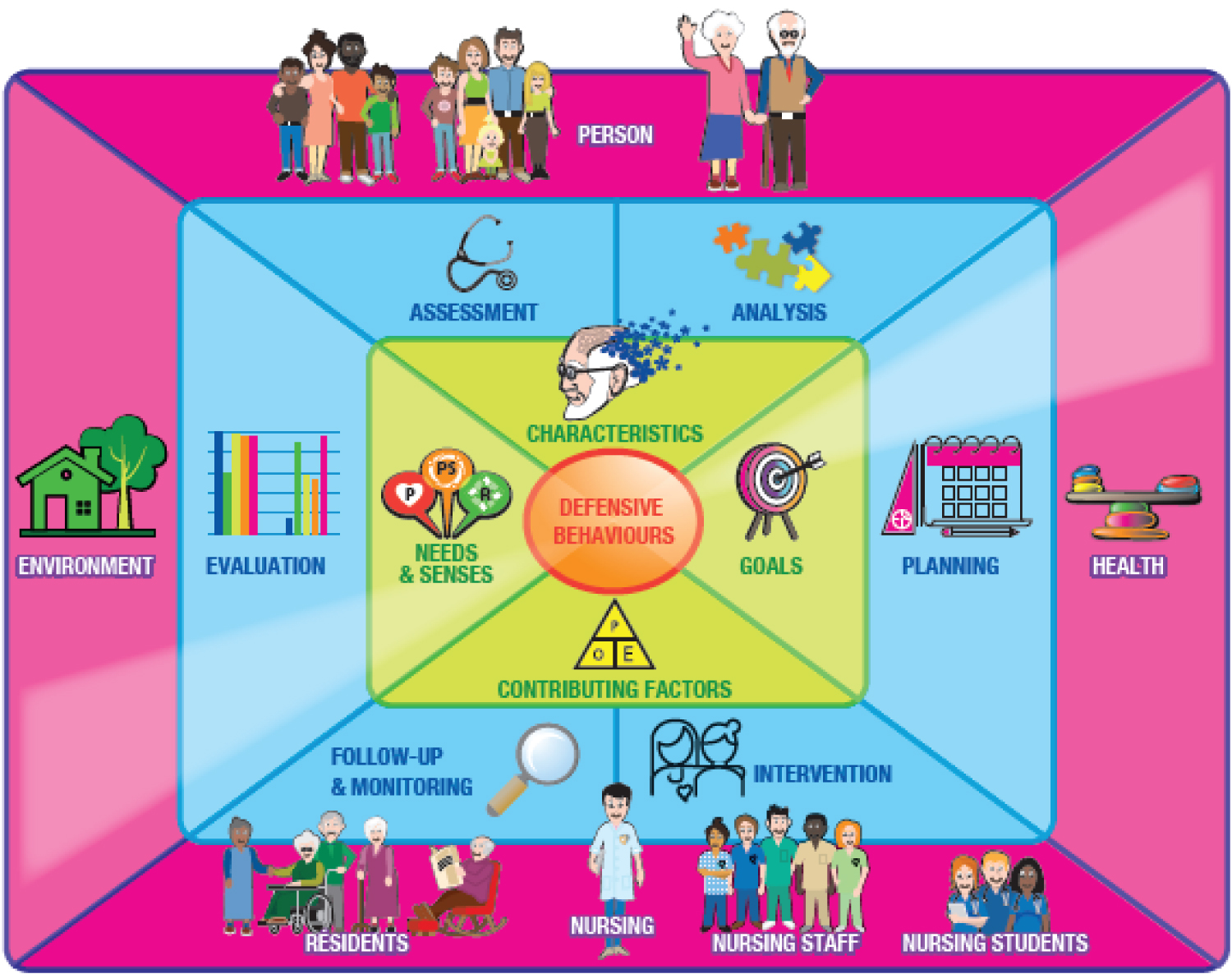

Based on Reed's proposal on mid-paradigm for knowledge development [91], and on Littzen, Langley, et Grant's proposal [92], we suggest a prismatic mid-paradigm for nursing care for people living with AD who show defensive behaviours. This prismatic mid-paradigm illustrates the main points of this article (Figure 2). Firstly, at a general level of knowledge, two outer circles surround the phenomenon of defensive behaviours. The pink outermost circle represents the four concepts of the nursing metaparadigm that Johnson's model defined. The intermediate blue circle integrates the previously introduced six steps of the clinical nursing process. At the specific level of knowledge, the green inner circle shows the essential pieces of knowledge for the care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours. Because we have chosen a relationship-centred approach of care and because of the context of defensive behaviours, many people are involved in our proposal. We can identify who are involved: The older persons (resident), their family, other residents living in the unit, the nurse, nursing staff, and nursing students.

Essential Nursing Knowledge for the Care of People Living with Alzheimer's Who Show defensive Behaviours

The essential nursing knowledge for the care of people living with Alzheimer's who show defensive behaviours is presented in four parts, which are 1) Characteristics of AD; 2) Goals of the behaviours; 3) Factors contributing to the expression of defensive behaviours, and 4) Ecobiopsychosocial and pharmacological interventions related to the person and family's needs. The main points concerning these essential pieces of knowledge are referred to in a general way rather than described in detail.

This article does not aim to replace a training course on the topics discussed.

First essential piece of nursing knowledge: Characteristics of AD

The first essential piece of nursing knowledge is related to the very characteristics of AD. The nurse must possess some essential pieces of knowledge to be able to understand the needs of a person living with AD.

Alzheimer's symptoms

Naturally, the nurse has to know that the main symptoms of AD are cognitive, i.e., memory, judgment, and reasoning, but also that the disease will have effects on physical, functional, and self-care abilities, as well as cause changes in emotions, moods, behaviours and communication abilities [93].

The nurse must also know well what are generally called the A's of AD. According to different authors [19,74,94,95], we can find between four and 11 Alzheimer's A's. The first seven A's relate to the neurocognitive effects of the disease, namely, amnesia, aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, anosognosia, altered perception, and attention. For these seven A's, the nurse must not only know what each word means, but also the impact on the everyday life of people living with AD, as well as ways to help them. The last four A's are connected to the behavioural and psychological symptoms, and are apathy, aggression, agitation, and anxiety. As for all the disease's symptoms, the nurse must be able to recognize them, know what factors can contribute to their onset, and which interventions are appropriate. Ideally, the nurse should promote strategies to prevent these phenomena.

Losses and language

Nurses must understand that people living with AD will experience successive and irretrievable losses. These losses are related to the stage of the disease: The more the disease progresses, the bigger the losses will be, and the bigger the need for help will be. Family members will also experience a process of loss and mourning related not just to their loved one, but also to their projects, habits, and roles.

The language of the person living with AD will become more and more affected. This means that the person will have more and more difficulties in clearly communicating his or her thoughts, feelings, and needs. The verbal language will deteriorate and be replaced by vocal and physical language. Vocal language is meaningful and can be related to the person's needs [96,97]. Physical language is related to all meaningful behaviours shown by the person, for example, grimaces, gestures, movements, and body postures or stiffness. Whether verbal, vocal or physical, defensive behaviours are always meaningful behaviours.

Retrogenesis model

It is very important that nurses know that the evolution of AD is usually described with the Retrogenesis Model in seven consecutive stages, from one to seven [98,99,100]. The Retrogenesis Model can helpfully explain the person's general functional capacities and losses, emotional and behavioural changes, as well as activities and care needs.

These seven stages can be organized in three levels of severity, i.e., mild, moderate, and severe [101], or in more inclusive stages described as being early, middle, late, or end-of-life [102]. Because the seven stages reverse "...the order of functional acquisition in normal human development" [100], it is possible to link the function, which is lost because of AD, with the approximate developmental age at which it is acquired [103,104]. Linking the stage of AD to the developmental age should not be used to infantilize the person, but rather to illustrate the level of help the person needs in their daily life [103,105].

In summary, the Retrogenesis Model is helpful to better understand the person's needs and behaviours, to better a dapt the environment, and to better plan daily activities and care.

Validation® approach

Nurses working with older adults living with AD should also be interested in Naomi Feil's proposals regarding the Validation® Approach [106]. This approach helps the person communicate his or her needs and feelings, and helps the family or formal caregiver to better understand intriguing behaviours shown by people living with AD. For example, when a 93-year-old woman wants to go home to take care of her young children who need her, or when an 88-year-old man says he has to go to work at 5:00 in the morning or his boss won't be happy, caregivers might feel confused. Using temporal and spatial reorientation techniques is useless and counterproductive and can even create anxiety or catastrophic reactions. Using the Validation® approach, however, will be helpful and soothing.

Be in the same place where, when, and how the person is: The Retrogenesis Model and the Validation®

The Retrogenesis Model and the Validation® approach lead nurses to consider the person's capacities, needs, and emotions, and help him or her to better understand the meaning of behaviours. This also guides nurses to always consider the perspective of the person's life history, which is indispensable for the nursing care of persons with AD. In fact, we can say it is fundamental that the nurse be able to encounter the person where, when, and how he or she is. That means that nurses must consider the person's capacities of doing and communicating, the level of space-time where the person is at, what he or she is experiencing, and the emotion and needs that are expressed.

Speaking of essential nursing knowledge for the care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours, nurses must understand the impact of stimuli on the person, and the person's threat perception and fear response.

Stimuli, threat perception, and fear response

As explained by GR Hall and Buckwalter [107], people living with AD present a reduction of the stress threshold. This phenomenon is in relation with the person's decreased capacity to manage internal or external stimuli according to their quantity and quality. This means that, placed in a situation where there are too many stimuli, the person living with AD may show reactive behaviours which can be defensive. For example, we can imagine a woman with severe stage (7b) AD who receives help for self-care. Imagine this woman feels pain, is cold, and gets afraid because one of the two carers is male. Imagine too that there is a lot of noise from the television and from discussion between the two caregivers. Therefore, unable to clearly explain what she is experiencing, this woman may express protective and defensive behaviours such as grab hold of her clothes, cry for help, reject caregivers, or try to bite them. Regarding the behaviours of the person, nurses must be mindful of the different internal and external stimuli in a way to promote pleasant stimuli in an adequate quantity according to the person's abilities, attention span, and needs.

It's also important to understand that, according to neurobiological principles, people living with AD have special sensitivity in terms of threat perception and fear response [108]. This means that the person may feel threatened by events considered trivial and respond to them with fearful behaviours that appear exaggerated.

Other neurocognitive diseases

Finally, nurses must also know of other neurocognitive diseases because of their specific characteristics. This permits the nurse to understand differences, well adapt his or her clinical process, and better evaluate the person's own situation. In the context of defensive behaviours, we can particularly think about people living with behavioural variant frontotemporal disease. Because of their illness, these people will be more likely to express impulsive, uninhibited, and inappropriate social behaviours. It is possible to say that specificities will change the way of intervening since effective interventions for people living with AD may not always be recommended for these individuals. We restate that this paper is centred on people living with AD, even if some explanations and recommendations could be useful for the care of people living with another neurocognitive disease such as frontotemporal disease.

After having presented the characteristics of AD, we can now examine the goals of the defensive behaviours.

Second essential piece of nursing knowledge: Goals of defensive behaviours

The second essential piece of nursing knowledge is to do with understanding the goals of defensive behaviours. Understanding the purpose of these behaviours is necessary to target answer the causes and propose efficient interventions which respond to the needs of people living with AD. As explained previously, aggressive behaviours should be considered as being relational, protective, and defensive [22,109]. This perspective is linked to different authors' proposals.

Firstly, it is important to consider all behaviours shown by people living with AD as legitimate because they are used to convey a message and are therefore meaningful [1,2].

Secondly, we can speak about a Theoretical Model for Aggression shown by people living with AD, proposed by Lanza [110]. Several theories based on the origins of aggression inspired her model. Lanza presents two major origins for aggression, which can be innate, or related to interactions with the environment. These factors may combine to create a potential for aggression that is then expressed verbally or non-verbally. The potential for aggression may also be unspoken and latent. This model explains well the unavoidable presence of factors for an expression of aggressiveness to happen. Ryden [111] used Lanza's model as a model to create a new instrument for measuring aggressive behaviours. Three years later, she took the same model for a study with the purpose to determine the nature, frequency, and context of aggressive behaviours shown by residents in a nursing home [112].

Thirdly, we can recall Johnson's theory (1980) which explains that behaviours have goals and functions, including protection and defence. We can also present Talerico's theoretical proposal for aggressive/protective behaviours in persons with AD based on Johnson's model [113]. This proposal has contributed to changing the way nurses view defensive behaviours shown by people with AD, and to a better understanding of their meaning and usefulness [114].

Fourthly, it is essential to mention the escalation phenomenon [115,116]. People living with AD may express verbal, vocal, or physical behaviours to communicate that they are uncomfortable or disagree with something that is said or done to them. If these behaviours are not understood or respected by the caregiver, the person may then seek to express their feelings more strongly. If this is still not understood or respected, then the person may adopt protective and defensive behaviours. This phenomenon of escalation needs to be understood as it allows for early identification of meaningful behaviours and promotes a response that is appropriate to the person's difficult experience. This proposal is particularly interesting in the context of personal care.

Fifthly, it is interesting to consider the nursing symptom theories. For example, from Dodd, et al. [117], we can understand that the behavioural response expressed by an individual is relative to the experienced symptoms and the perception and assessment of those symptoms. If the symptoms are negative or perceived as threatening to the integrity, the person may show defensive behaviours.

Once having understood the goal of defensive behaviours, it is essential to consider the factors contributing to the expression of these behaviours.

Third essential piece of nursing knowledge: Factors contributing to the expression of defensive behaviours

The third essential piece of nursing knowledge is centred on the understanding of the causes contributing to the expression of defensive behaviours. As said by Holst and Skär, et al. [12], formal caregivers need to be able to identify factors triggering defensive behaviours.

Indeed, as currently reported [10,20,23,32,73,118,119], responsive behaviours, and therefore aggressive ones, are related to different factors linked to the person, others, and the environment. Many studies describe these different factors [5,13-15,17,26-29,79,110,114,120-133].

While considering factors contributing to defensive behaviours, we can refer to Algase and collaborators' now classic need-driven dementia-compromised behaviour theory [20]. This theory explains that compromised needs may lead the person to show reactive behaviours, for example, defensive ones. These compromised needs are related to contextual and proximal factors. Based on this theory and other theoretical propositions and research data [10,19,23,30,32,52,72,75,94,107,110,130,134,135], we can present the factors contributing to the expression of defensive behaviours. As previously explained, this article does not intend to replace nursing teaching on reactive and defensive behaviours shown by people living with AD. Therefore, the factors are simply cited without being explained. Cited references allow for location of sources, and those interested in obtaining more information can write to the first author.

The first few factors are related to the general portrait of the person, namely, the neurological, cognitive, and psychosocial factors, as well as their general health status. These background factors shape a person's basic risk profile. They are presented in the table (Table 1).

The second set of factors are related to the proximal factors namely, the personal environment as well as those relative to the social and physical environment. Considering the personal needs, we integrated Boettcher's needs related to the violent behaviour prevention [134]. We also added organisational factors. All these proximal factors generally precipitate the behaviour. They are presented in the table below (Table 2).

Rigorous clinical process

As mentioned previously, nurses who care for persons living with AD who show defensive behaviours must complete a rigorous clinical process (Figure 1). Many proposals exist on the nursing clinical process to be conducted when a person shows reactive behaviours. Based on these proposals as well as on the Fundamentals of Care Framework and Practice Process, a complete form comprising the nursing clinical process specific to people showing defensive behaviours will be further presented (Part 2).

Fourth essential piece of nursing knowledge: Interventions related to the needs, triggers, and Senses

Nurses who care for people living with AD and showing defensive behaviours must know various intervention strategies. These strategies must always target the triggers of the defensive behaviours as well as the needs of the person, taking into consideration his or her capacities and interests [10]. We want to reiterate that this article cannot replace a nursing teaching on interventions for people living with AD who show defensive behaviours and their families. Therefore, we simply present general principles.

Because the interventions target the factors contributing to the defensive behaviours expression and because these factors are related to the person, others, and the environment, we adopt the perspective of ecobiopsychosocial interventions proposed by Gerlach and Kales [23]. The "eco" part of the term is related to the physical and organizational environment. The "bio" part relates to physical needs. The "psycho" part relates to the psychosocial needs. Finally, the "social" part targets other people, for example, family members, formal carers, and other residents. Considering these ecobiopsychosocial components, it is easy to create links with the physical, psychological, and relational needs described in the FOC Framework. It is also easy to establish relations with the proximal factors and Boettcher's nine needs.

These interventions can also be described according to the kind of intervention strategy. We can therefore refer to the proposal by Wolf, Goldberg, and Freedman [136], who present seven general strategies for people living with AD who show agitated or defensive behaviours. These strategies are: 1) Physical activity; 2) Sensory enhancement; 3) Social interaction; 4) Purposeful engagement; 5) Environmental design; 6) Differential reinforcement, and 7) Staff/caregiver education.

Senses framework

Speaking of interventions, we have also considered with attention the Senses Framework proposed by Nolan, et al. [52]. This framework suggests six Senses experienced in the best care environments by everyone, i.e., the older person being cared for, their family carers, nursing staff, and nursing students, to which we add other residents living in the unit. These Senses are linked with enriched environments of care [52] where people can have positive experiences. According to the authors, a relationship-centred approach to care would be more likely to support the achievement of these six Senses rather than a person-centred approach. These six Senses are presented in the table (Table 3). This framework also describes factors which contribute to creating the six Senses, permitting its implementation. Working to promote these factors in care settings could contribute to a better care experience for everyone [52], which we think is very important. The Senses Framework guide a systematic scoping review protocol on physically aggressive behaviors in older people living with cognitive disorders by Bourbonnais, Goulet, et al. [137].

Regarding the intervention's implementation, guidelines explain the importance to apply the care plan with rigour and 24/7 consistency. It is also important to investigate the feasibility of interventions and to support caregivers and family members in carrying them out. It is critical to set outcome measures and diligently monitor the effects of interventions.

Strategies to prevent and defuse incidents

Nursing home nurses and managers should adopt preventive strategies for dealing with defensive behaviours. For example, Fitzwater and Gates [138,139] propose a violence prevention checklist with 12 skills. Also, Caspi [27] proposes 12 care staff strategies to prevent and defuse incidents between residents. These strategies are centred around the resident showing defensive behaviours, i.e., refocusing, diverting, offering a walk, and never arguing. Other strategies are directed at other residents and groups of residents, i.e., redirecting to another area, positioning and repositioning seating arrangements, or even separating residents. Finally, some strategies target carers themselves, i.e., being alert and proactive, being informed of previous incidents, staying calm, and seeking help.

Acting competently in the presence of defensive behaviours

Defensive behaviours can be expressed despite good prevention and intervention strategies. In this case, nurses and all health care personnel should be trained to use specific intervention techniques. These techniques are designed not only to avoid escalation to assaultive behaviours, but also to protect the carers themselves and the people around them, and to redirect a person showing protective and defensive behaviours. Because of the more fragile profile of older adults and the specificities of neurocognitive diseases, intervention techniques should not be the same as those used with adults suffering from other mental health problems and in crisis situations. An example of inspiring training is the Gentle Persuasive Approaches (GPA®) in Dementia Care offered in Ontario by Schindel Martin, Loiselle, et al. [4,19,140,141].

Pharmacological interventions

Finally, we must talk about pharmacological interventions. Some recommendations and guidelines exist regarding pharmacological interventions for people showing reactive behaviours, and more particularly, defensive ones.

We approach pharmacological treatment for people living with AD who show defensive behaviours with a beneficial-use perspective based on guidelines, experts' recommendations, as well as Kales', et al. [74] and Tisher and Salardini's [142] proposals. It is possible to summarize this pharmacological subject with four categories of principles. The first principle is related to disease and health factor-modifying interventions. These treatments can retard the progression of AD, since it is not yet possible to stop it, or to treat it as health problems such as infection or constipation. The second principle of treatment is centred on compromised needs and unpleasant symptoms, which could be pain, depressive symptoms, anxiety, or disturbing hallucinations. The third principle of treatment is related to safety risk. When faced with an imminent risk of aggression toward oneself or others, psychotropic drugs should be used to treat the person. Finally, the fourth principle of treatment is related to harm minimization - and drug misuse. This principle is linked to optimal use of drugs for people living with dementia. Every pharmacological prescription should be established through an in-depth assessment of health and underlying causes, and not be based solely on the state of defensive behaviours. It is also essential to consider preliminary and concomitant ecobiopsychosocial interventions have been implemented.

Moreover, a thoughtful follow-up of therapeutic effects, adverse effects, as well as treatment acceptability and observance must be done.

Conclusion

Defensive behaviours shown by people living with AD is a crucial challenge in nursing. Indeed, these behaviours frequently mean that the person has unmet needs and is placed in a situation where several triggering factors produce a bad experience. Moreover, defensive behaviours may have disastrous consequences not only for persons who show such behaviours, but also for all people involved, namely, the family members, other residents, and nursing staff.

Considering all these facts, we have referred to general and situation-specific levels of knowledge to build a proposal based on four essential pieces of knowledge for these nurses. Our proposal is constructed around a relationship-centred care perspective and is rooted in the FOC Framework. Our proposal is well illustrated by the prismatic mid-paradigm for nursing care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours. The first essential piece of knowledge is related to the characteristics of the person living with AD and the characteristics of the disease itself. The second essential piece of knowledge refers to the goals of defensive behaviours, which are undoubtedly important to understand. The third essential piece of knowledge is built with factors contributing to the expression of defensive behaviours. Finally, the fourth essential piece of knowledge is constituted with the principles guiding the choice and implementation of the ecobiopsychosocial and pharmacological interventions.

The first part of this article represented the essential prerequisite part leading to the very practical and precise formulation regarding nursing care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours. The second part will therefore introduce the Situation-Specific Fundamentals of Care Practice Process, which is essential for nurses and nursing students caring for people living with AD who show defensive behaviours.

This article represents a first version of our proposal and is bound to evolve with new theoretical proposals and developments, and the conceptual work of the authors.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

Because the nurses working in nursing homes occupy a central place in the care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours, they must be able to assess the person's needs and determine judicious interventions. Moreover, nurses must have a broader perspective than person-centred care since they also take care of the person's family members and other residents living in the unit, and they must support formal carers. Therefore, nurses working in nursing homes must adopt a relationship-centred perspective of care which is, in our view, well integrated in the FOC Framework. Finally, being the leaders of the nursing staff, monitoring nursing students, and occupying an important role in the interprofessional team, nurses must possess knowledge related to people living with AD as well as a specific body of knowledge centred on defensive behaviours.

Nursing must be rooted in relevant theoretical explanations. That is why, before proposing a practice process for the nursing care of people living with AD who show defensive behaviours, we must build and present the theoretical foundations of our proposal.

The general level of knowledge of gerontological nursing practice describes the recommendations made about the specific clinical expertise that nurses must possess. This general perspective can bring into light some differences between countries related to the organization of health care, modes of professional training, nursing roles, and professional laws and rules. It is therefore important to specify this level of knowledge depending on the context of practice. Despite this, there are still extremely important proposals to be considered regardless of the practice setting. This level of knowledge is useful to guide and organize the clinical nursing practice and provide guidance on the level and scope of competence that nurses should have to be able to practice.

Regarding the situation-specific level of knowledge, we can find theoretical proposals and research data which are centred around persons living with AD who show defensive behaviours. We can say that the situation-specific level of knowledge is more universal than the general level of knowledge. The elements proposed directly target the different nursing practice components. This situation-specific knowledge may also be useful in planning the curriculum and training for nurses or nursing students.

It is important to understand that these two levels of knowledge deal with the advancement of knowledge and evolution of professional practices and must therefore be rigorously updated. Thus, this proposal cannot be established once and for all, and will have to be updated and completed regularly. It is only by demonstrating rigour that such proposals can be useful for clinical nursing practice.

Finally, it is important to realise that clinical nurses or nursing students cannot easily transfer such proposals into their daily practice. Therefore, it is essential to propose a clinical practice process which is dedicated to supporting nurses in the concrete integration of this knowledge into their professional and clinical practice. Additionally, such a practical process can also enable nurse educators to make their explanations more concrete. Finally, a practice process provides step-by-step guidance for the clinical approach of nursing students when they are doing an internship or their work. Since such a tool is essential to the application of the knowledge presented in this article, we are pleased to further explain the FOC Practice Process specific to the person living with AD and showing defensive behaviours in the following, second part (Appendix).

Acknowledgements

Rebecca Feo, PhD, BPysch Hons, College of Nursing & Health Sciences, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Susa Bernard, Master's Degree in Social Sciences, Director of Susa English, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada.

Philippe Charbonnier, Graphist

Dr. Sonya Morales, Copyright Office, Laval University

Conflict of Interest Statement

None.

Funding

None.

References

- Dupuis SL, Wiersma E, Loiselle L (2012) Pathologizing behavior: Meanings of behaviors in dementia care. Journal of Aging Studies 26: 162-173.

- Macaulay S (2018) The broken lens of BPSD: Why we need to rethink the way we label the behavior of people who live with Alzheimer disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc 19: 177-180.

- Dupuis SL, Luh J (2005) Understanding responsive behaviours: The importance of correctly perceiving triggers that precipitate residents' responsive behaviours. Canadian Nursing Home 16: 29-34.

- Schindel Martin L, Dupuis S (2005) Gentle persuasive approaches curriculum. The development and pilot evaluation of an educational program to train long-term care front-line staff in the management of responsive behaviours of a more catastrophic nature associated with dementia. Hamilton, Canada: Advanced Gerontological Education.

- Jutkowitz E, Brasure M, Fuchs E, et al. (2016) Care-Delivery Interventions to Manage Agitation and Aggression in Dementia Nursing Home and Assisted Living Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 64: 477-488.

- Volicer L (2012) Toward better terminology of behavioral symptoms of dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 13: 3-4.

- Volicer L, Citrome L, Volavka J (2017) Measurement of agitation and aggression in adult and aged neuropsychiatric patients: Review of definitions and frequently used measurement scales. CNS Spectrums 22: 407-414.

- Volicer L, Galik E (2018) Agitation and aggression are 2 different syndromes in persons with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 19: 1035-1038.

- de Oliveira AMD, Radanovic M, de Mello PC, et al. (2015) Nonpharmacological interventions to reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review. BioMed Res Int 2015: 218980.

- Dettmore D, Kolanowski A, Boustani M (2009) Aggression in persons with dementia: Use of nursing theory to guide clinical practice. Geriatr Nurs 30: 8-17.

- Eastley R, Wilcock GK (1997) Prevalence and correlates of aggressive behaviours occurring in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 12: 484-487.

- Holst A, Skär L (2017) Formal caregivers' experiences of aggressive behaviour in older people living with dementia in nursing homes: A systematic review. Int J Older People Nurs 12: e12158.

- Liljegren M, Waldö ML, Englund E (2018) Physical aggression among patients with dementia, neuropathologically confirmed post-mortem. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry 33: e242-e248.

- Paschali M, Kamp D, Reichmann C, et al. (2018) A systematic evaluation of impulsive-aggressive behavior in psychogeriatric inpatients using the staff observation aggression scale-revision (SOAS-R). International Psychogeriatrics 30: 61-68.

- Backhouse T, Camino J, Mioshi E (2018) What do we know about behavioral crises in dementia? A systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis 62: 99-113.

- Perlman CM, Hirdes JP (2008) The aggressive behavior scale: A new scale to measure aggression based on the minimum data set. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56: 2298-2303.

- Voyer P, Verreault R, Azizah GM, et al. (2005) Prevalence of physical and verbal aggressive behaviours and associated factors among older adults in long-term care facilities. BMC Geriatrics 5: 13.

- Miller JD, Lynam DR (2006) Reactive and proactive aggression: Similarities and differences. Personality and Individual Differences 41: 1469-1480.

- Schindel Martin L, Loiselle L, Montemuro M, et al. (2016) Gentle Persuasive Approaches (GPA®) in dementia care: Supporting persons with responsive behaviours. (3rd edn), Hamilton, Canada: Advanced Gerontological Education (AGE) Inc.

- Algase DL, Beck CH, Kolanowski A, et al. (1996) Need-driven dementia-compromised behavior: An alternative view of disruptive behavior. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias 11: 10-19.

- Schindel Martin L, Gillies L, Coker E, et al. (2016) An education intervention to enhance staff self-efficacy to provide dementia care in an acute care hospital in Canada: A nonrandomized controlled study. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias 31: 664-677.

- Talerico KA, Evans LK (2000) Making sense of aggressive/protective behaviors in persons with dementia. Alzheimer's Care Quarterly 1: 77-88.

- Gerlach LB, Kales HC (2018) Managing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Psychiat Clin North Am 41: 127-139.

- Sun M, Mainland BJ, Ornstein TJ, et al. (2018) Correlates of nursing care burden among institutionalized patients with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics 30: 1549-1555.

- Nybakken S, Strandås M, Bondas T (2018) Caregivers' perceptions of aggressive behaviour in nursing home residents living with dementia: A meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs 74: 2713-2726.

- Stutte K, Hahn S, Fierz K, et al. (2017) Factors associated with aggressive behavior between residents and staff in nursing homes. Geriatric Nursing 38: 398-405.

- Caspi E (2015) Aggressive behaviors between residents with dementia in an assisted living residence. Dementia 14: 528-546.

- Murphy B, Bugeja L, Pilgrim J, et al. (2017) Deaths from resident-to-resident aggression in Australian nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 65: 2603-2609.

- Rosen T, Pillemer K, Lachs M (2008) Resident-to-resident aggression in long-term care facilities: An understudied problem. Aggression and Violent Behavior 13: 77-87.

- Gillis K, Lahaye H, Dom S, et al. (2019) A person-centred team approach targeting agitated and aggressive behaviour amongst nursing home residents with dementia using the Senses Framework. Int J Older People Nurs14: e12269.

- Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG (2012) Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. JAMA 308: 2020-2029.

- Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG (2015) Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ 350: 369.

- Kim HS (2012) The role of theory in clinical nursing practice. Klinisk Sygepleje 26: 16-29.

- Kim HS (2015) The essence of nursing practice. Pphilosophy and perspective. NY: Springer Publishing Company, New York.

- Fawcett J, DeSanto-Madeya S (2013) Contemporary Nursing Knowledge. Analysis and Evaluation of Nursing Models and Theories. (3rd edn), F.A. Davis Company, Philadelphia, PA.

- Kitwood T (1993) Discover the person not the disease. Journal of Dementia Care 1: 16-17.

- Kitwood T (1997) Dementia Reconsidered. The Person comes first. Buckingham, Open University Press, United Kingdom.

- McCormack B, McCance T (2017) Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care. Theory and Practice (2nd edn), Wiley Blackwell Chichester, United Kingdom.

- Darveau B, Boulard B (2015) Accompanying the family living with a person with Alzheimer's disease (FRENCH Book). In: F Duhame, Health and Family. A Systemic Approach to Nursing. (3rd edn), Chenelière Éducation, Montreal, QC, 225-245.

- Eliopoulos C (2018) Gerontological Nursing. (9th edn), Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia, PA.

- White DL, Cartwright JC (2018) Family health in mid- and later life. In: JR Kaakinen, DP Coehlo, R Steele, et al. (6th edn), Family health care nursing: Theory, practice, and research, FA Davis Company, Philadelphia P: 457-496.

- West CH, Jakubec SL (2019) Family Nursing. In BJ Astle, W Duggleby (Eds), Canadian Fundamentals of Nursing. (6th edn.), Elsevier, Milton, Canada, 307-323.

- Conroy T, Feo R, Alderman J, et al. (2016) Building nursing practice: The Fundamentals of Care Framework. In: J Crisp, C Douglas, C Rebeiro, D waterse ,Potter and Perry's Fundamentals of Nursing - Australian Version. (5th edn), Elsevier Australia. Chatswood, NSW, 15-28.

- de Witt L, Fortune D (2019) Relationship-Centered Dementia Care: Insights from a Community-Based Culture Change Coalition. Dementia 18: 1146-1165.

- Dewar B, MacBride T (2017) Developing Caring Conversations in care homes: An appreciative inquiry. Health Soc Care in the Community 25: 1375-1386.

- Dewar B, Nolan M (2013) Caring about caring: Developing a model to implement compassionate relationship centred care in an older people care setting. Int J Nurs Stud 50: 1247-1258.

- Doane GH, Varcoe C (2015) How to Nurse: Relational Inquiry with Individuals and Families in Changing Health and Health Care Context. Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia, PA.

- Feo R, Rasmussen P, Wiechula R, et al. (2017) Developing effective and caring nurse-patient relationships. Nurs Stand 31: 54-63.

- Jablonski-Jaudon RA, Kolanowski AM, Winstead V, et al. (2016) Maturation of the MOUTh Intervention: From Reducing Threat to Relationship-Centered Care. J Gerontol Nurs 42: 15-23.

- Kitwood T (1993) Towards a theory of dementia care: The interpersonal process. Ageing and Society, 13: 51-67.

- Kitwood T, Bredin K (1992) Person to Person. A guide to the care of those with failing mental powers (2nd edn), Gale Centre Publications, Loughton, United Kingdom.

- Nolan M, Brown J, Davies S, et al. (2006) The senses framework: Improving care for older people through a relationship-centred approach. Getting research into practice (GRiP) report No 2. Project Report. University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom. P: 1-153.

- Nolan M, Davies S, Brown J, et al. (2004) Beyond person-centred care: a new vision for gerontological nursing. J Clin Nurs 13: 45-53.

- Dupuis SL, McAiney CA, Fortune D, et al. (2016) Theoretical foundations guiding culture change: The work of the Partnerships in Dementia Care Alliance. Dementia 15: 85-105.

- Partnerships in dementia care (nd) Moving from person-centred care to relationship-centred care.

- Kitson A (2018) The fundamentals of care framework as a point-of-care nursing theory. Nurs Res 67: 99-107.

- Rey S, Voyer P, Bouchard S, et al. (2020) Finding the fundamental needs behind resistance to care: Using the fundamentals of care practice process. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29: 1774-1787.

- Kitson A, Conroy T, Kuluski K, et al. (2013) Reclaiming and redefining the fundamentals of care: Nursing's response to meeting patients' basic human needs. School of Nursing, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia.

- Feo R, Conroy T, Jangland E, et al. (2018) Towards a standardised definition for fundamental care: A modified Delphi study. J Clin Nurs 27: 2285-2299.

- Johnson DE (1980) The behavioral system model for nursing. In: JP Riehl, C Roy, Conceptual models for nursing practice. (2nd edn), NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York, 207-216.

- (2017) Entry-to-practice gerontological care. Competencies for baccal aureate programs in nursing. Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing, Ottawa, Canada.

- Canadian Gerontological Nursing Association (2010) Gerontological nursing competencies and standards of practice 2010. Canadian Gerontological Nursing Association, Vancouver, Canada.

- Canadian Gerontological Nursing Association (2019) Gerontological nursing standards of practice and competencies. (4th edn), Canadian Nurses Association, Toronto, Canada.

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors' Mental Health (2006) The assessment and treatment of mental health issues in long-term care (focus on mood and behaviour). Canadian Coalition for Seniors' Mental Health, Toronto, Canada.

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors' Mental Health (2014) The assessment and treatment of mental health issues in long-term care (focus on mood and behaviour) - 2014 Update. Canadian Coalition for Seniors' Mental Health, Toronto, Canada.

- International Psychogeriatric Association (2012) Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BPSD. Nurses' Guide to BPSD. Northfield, IL: International Psychogeriatric Association.

- International psychogeriatric association (2012) The IPA complete guides to behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Specialists guide. Specialists, Primary Care Physicians, Nurses. Milwaukee, WI: International Psychogeriatric Association.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. NICE Guideline.

- Ngo J, Holroyd-Leduc JM (2015) Systematic review of recent dementia practice guidelines. Age and Ageing 44: 25-33.

- (2019) RACGP aged care clinical guide (Silver Book) 5th edition Part A. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia General Melbourne, Australia, Royal Australian College of General Practioners.

- The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (2013) Assessment and management of people with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). A handbook for NSW health clinicians.

- Adams-Fryatt A, Bochuka K, Carrido C, et al. (2010) Using P.I.E.C.E.S. to uncover the meaning of behaviour. Canadian Nursing Home 21: 4-7.

- Buettner LL, Fitzsimmons S (2009) N.E.S.T. Approach: Dementia Practice Guidelines for Disturbing Behaviors. Needs - Environment - Stimulation - Techniques. Venture Publishing, State College, PA.

- Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG (2019) The DICETM approach. Guiding the caregiver in managing the behavioral symptoms of dementia. Ann Horbor, Michigan Publishing Services.

- Kovach CR, Noonan PE, Reynolds S, et al. (2005) The Serial Trial Intervention (STI) teaching manual: An innovative approach to pain and unmet need management in people with late stage dementia. An in-service education program for professional caregivers of people with dementia. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, USA.

- Kovach CR, Noonan PE, Schlidt AM, et al. (2006) The serial trial intervention: an innovative approach to meeting needs of individuals with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs 32: 18-25.

- Kratiuk-Wall S, Quirke S, Heal C, et al. (nd). The TECH Approach to Dementia Care. Centre for Education and research on Ageing.

- Brechin D, Murphy G, James IA, et al. (2013) Alternatives to antipsychotic medication: Psychological approaches in managing psychological and behavioural distress in people with dementia. The British Psychological Society, Leicester, UK.

- Tible OP, Riese F, Savaskan E, et al. (2017) Best practice in the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders 10: 297-309.

- Bellar A (2002) The influence of the environment on resistiveness to care and the effectiveness of an intervention to decrease resistiveness to care in people with Alzheimer's disease residing in institutions. Wayne State University, Detroit, USA.

- Cohen-Mansfield J (2000) Nonpharmacological Management of Behavioral Problems in Persons with Dementia: The TREA Model. Alzheimer's Care Quarterly 1: 22-34.

- Maxfield MC, Lewis RE, Cannon S (1996) Training staff to prevent aggressive behavior of cognitively impaired elderly patients during bathing and grooming. J Gerontological Nurs 22: 37-43.

- Mickus MA, Wagenaar DB, Averill M, et al. (2002) Developing effective bathing strategies for reducing problematic behavior for residents with dementia: The PRIDE Approach. Journal of Mental Health and Aging 8: 37-43.

- Schindel Martin L, Rozon L, McDowell S, et al. (2004) Evaluation of a training program for long-term care staff on bathing techniques for persons with dementia. Alzheimer's Care Quarterly 5: 217-229.

- Kaakinen JR (2018) Family nursing assessment and intervention. In: JR Kaakinen, DP Coehlo, R Steele, et al., Family Health Care Nursing: Theory, Practice, and Research. (6th edn), FA Davis Company, Philadelphia, 113-146.

- Moyle W, Bramble M, Bauer M, et al. (2016) They rush you and push you too much ... and you can't really get any good response off them: A qualitative examination of family involvement in care of people with dementia in acute care. Australas J Ageing 35: E30-34.

- Hutchinson A, O'Qonnell B, Rawson H, et al. (2015) The Tri-focal Model of Care: building staff capacity for partnership-centred, evidence-based residential aged care. Aust Nurs Midwifery J 23: 43.

- Hutchinson A, Rawson H, O'Connell B, et al. (2017) Tri-focal model of care implementation: Perspectives of residents and family. J Nurs Scholarsh 49: 33-43.

- Nolan M, Davies S, Grant G (2001) Working with older people and their families. Key issues in policy and practice. Open University Press, Philadelphia.

- Nolan M, Lundh U, Grant G, et al. (2003) Partnerships in Family Care: understanding the caregiving career. PA: Open University Press, Philadelphia.

- Reed PG (2020) Moving on: From metaparadigm to midparadigm for knowledge development. Nursing Science Quarterly 33: 38-40.

- Littzen COR, Langley CA, Grant CA (2020) The Prismatic midparadigm of nursing. Nurs Sci Q 33: 41-45.

- Kruse GL (2019) Older Persons. Canadian content written by Sherry Dahlke & Wendy Duggleby. In: B. J. Astle & W. Duggleby, Canadian Fundamentals of Nursing. (6th edn), Milton, Canada: Elsevier, 411-431.

- Hamilton P, Harris D, Le Clair K, et al. (2010) "Putting the P.I.E.C.E.S. Together". A model for collaborative care and changing practice. A learning resource for providers caring for older adults with complex physical and cognitive/mental health needs and behavioural changes. (6th edn), Fall Rivers (NS), P.I.E.C.E.S. Consult Group.

- Steele CD (2011) Nurse to Nurse. Dementia care. Expert interventions. McGraw Hill 25: 31.

- Bourbonnais A, Ducharme F (2010) The meanings of screams in older people living with dementia in a nursing home. Int Psychogeriatr 22: 1172-1184.

- Bourbonnais A, Ducharme F, Landreville P, et al. (2019) Effects of an intervention approach based on the meanings of vocal behaviours in older people living with a major neurocognitive disorder: A pilot study. Science of Nursing and Health Practices 2: 1-15.

- Auer S, Reisberg B (1997) The GDS/FAST staging system. Int Psychogeriatr 9: 167-171.

- Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, et al. (1982) The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. American Journal of Psychiatry 139: 1136-1139.

- Reisberg B, Kenowsky S, Franssen EH, et al. (1999) Towards a science of Alzheimer's disease management: A model based upon current knowledge of retrogenesis. International Psychogeriatrics 11: 7-23.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders. DSM-5. (5th edn), American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, DC, London.

- Alzheimer's Society (2019) Stages of Alzheimer's disease.

- Carson VB, Vanderhorst KJ, Koenig HG (2015) Care giving for Alzheimer's Disease: A compassionate guide for clinicians and loved ones. Springer, New York.

- Rubial-Alvarez S, de Sola S, Machado MC, et al. (2013) The comparison of cognitive and functional performance in children and Alzheimer's disease supports the retrogenesis model. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 33: 191-203.

- Amdam L, Somers S (2018) Retrogenesis.

- Feil N (1994) The validation breakthrough. Simple techniques for communicating with people with "Alzheimer's-Type Dementia". Health Professions Press, Baltimore, MD, USA.

- Hall GR, Buckwalter KC (1987) Progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer's disease. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1: 399-406.

- Jablonski RA, Therrien B, Kolanowski A (2011) No more fighting and biting during mouth care: applying the theoretical constructs of threat perception to clinical practice. Res Theory Nurs Pract 25: 163-175.

- Schindel-Martin L, Morden P, Cetinski G, et al. (2003) Teaching staff to respond effectively to cognitively impaired residents who display self-protective behaviors. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias 18: 273-281.

- Lanza ML (1983) Origins of aggression. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 21: 11-16.

- Ryden MB (1988) Aggressive behavior in persons with dementia who live in the community. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 2: 342-355.

- Ryden MB, Bossenmaier M, McLachlan C (1991) Aggressive behavior in cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Research in Nursing and Health 14: 87-95.

- Talerico KA (1999) Correlates of aggressive behavioral actions of older adults with dementia. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

- Talerico KA, Evans LK, Strumpf NE (2002) Mental health correlates of aggression in nursing home residents with dementia. Gerontologist 42: 169-177.

- Belzil G, Vezina J (2015) Impact of caregivers' behaviors on resistiveness to care and collaboration in persons with dementia in the context of hygienic care: An interactional perspective. Int Psychogeriatr 27: 1861-1873.

- Woods DL, Rapp CG, Beck C (2004) Escalation/de-escalation patterns of behavioral symptoms of persons with dementia. Aging & Mental Health 8: 126-132.

- Dodd M, Janson S, Facione N, et al. (2001) Advancing the science of symptom management. J Adv Nurs 33: 668-676.

- Vickland V, Chilko N, Draper B, et al. (2012) Individualized guidelines for the management of aggression in dementia - Part 2: Appraisal of current guidelines. International Psychogeriatrics 24: 1125-1132.

- Volicer L, Hurley AC (2015) Assessment scales for advanced dementia. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press.

- Bradford A, Shrestha S, Snow AL, et al. (2012) Managing pain to prevent aggression in people with dementia: A nonpharmacologic intervention. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 27: 41-47.

- Brodaty H, Low LF (2003) Aggression in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 36-43.

- Burshnic VL, Douglas NF, Barker RM (2018) Employee attitudes towards aggression in persons with dementia: Readiness for wider adoption of person-centered frameworks. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 25: 176-187.

- Cen X, Li Y, Hasselberg M, et al. (2018) Aggressive behaviors among nursing home residents: Association with dementia and behavioral health disorders. J Am Medi Dir Assoc 19: 1104-1109.

- Choi SS, Budhathoki C, Gitlin LN (2017) Co-Occurrence and predictors of three commonly occurring behavioral symptoms in dementia: Agitation, aggression, and rejection of care. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry 25: 459-468.

- Hall KA, O'Connor DW (2004) Correlates of aggressive behavior in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 16: 141-158.

- Leonard R, Tinetti ME, Allore HG, et al. (2006) Potentially modifiable resident characteristics that are associated with physical or verbal aggression among nursing home residents with dementia. Arch Intern Med 166: 1295-1300.