Bilateral Empyema after Robotic Paraesophageal Hernia Repair: A Case Report

Abstract

Modern paraesophageal hernia repairs are typically performed via a laparoscopic or robotic approach, with or without mesh, and typically include some degree of fundoplication following closure of the hiatus. Known complications include slippage of wrap, esophageal perforation, vagal damage, and damage to nearby structures. We present a previously undescribed complication of bilateral empyema following robotic paraesophageal hernia repair with Nissen fundoplication. The patient was managed with chest tube insertion and administration of intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy with complete resolution of empyema. This report documents the presentation and management of a previously undescribed complication following robotic paraesophageal hernia repair.

Keywords

Robotic surgery, Anti-reflux surgery, Empyema, Paraesophageal hernia repair

Introduction

Surgical repair of paraesophageal hernias with fundoplication in patients with established history of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) provides effective symptom relief [1]. Modern paraesophageal hernia repairs are typically performed via a laparoscopic or robotic approach, with or without mesh, and typically include some degree of fundoplication following closure of the hiatus. Current trends and literature support robotic approaches to paraesophageal hernia repair as a superior method to standard laparoscopic approaches [1,2]. While established as a safe procedure, known complications include slippage of wrap, esophageal perforation, vagal damage, and damage to nearby structures. Previously undescribed is delayed presentation of bilateral empyema following paraesophageal hernia repair without mesh. In this report, we describe a previously undocumented complication of large bilateral posterior empyema following robotic paraesophageal hernia repair with Nissen fundoplication.

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old female with a 5 cm hiatal hernia, long-standing history of GERD, morbid obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea was referred to our specialized foregut surgery center. The patient endorsed lack of relief with proton pump inhibitors and worsening dysphagia to food for the last five years. Esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD) demonstrated Los Angeles grade C and D gastritis and a 5 cm hiatal hernia. Esophageal manometry revealed a hypotensive lower esophageal sphincter with abnormal esophageal contractility suspected to be secondary to uncontrolled GERD.

The patient subsequently underwent robotic paraesophageal hernia repair with Nissen fundoplication. The mediastinal dissection proceeded appropriately and with relatively non-complicated dissection planes. 6 cm of intraabdominal esophageal length, standard for our repairs, was obtained and the hiatus was closed posteriorly with running, self-retaining permanent suture. After closure of the hiatus, a 58 French Maloney bougie was placed with difficulty to size the Nissen fundoplication. Following the completion of the wrap, an EGD was performed demonstrating adequate position of wrap and easy transit of scope through the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) into stomach. A small 1 cm mucosal tear was noted in the distal esophagus immediately proximal to GE junction. Air was sequentially insufflated into the distal esophagus and gastric body concurrently with submergence of the GEJ and distal esophagus in irrigation fluid. No bubbles, an indicator of esophageal or gastric leak, were observed and the procedure concluded. The patient was discharged without incident the following day.

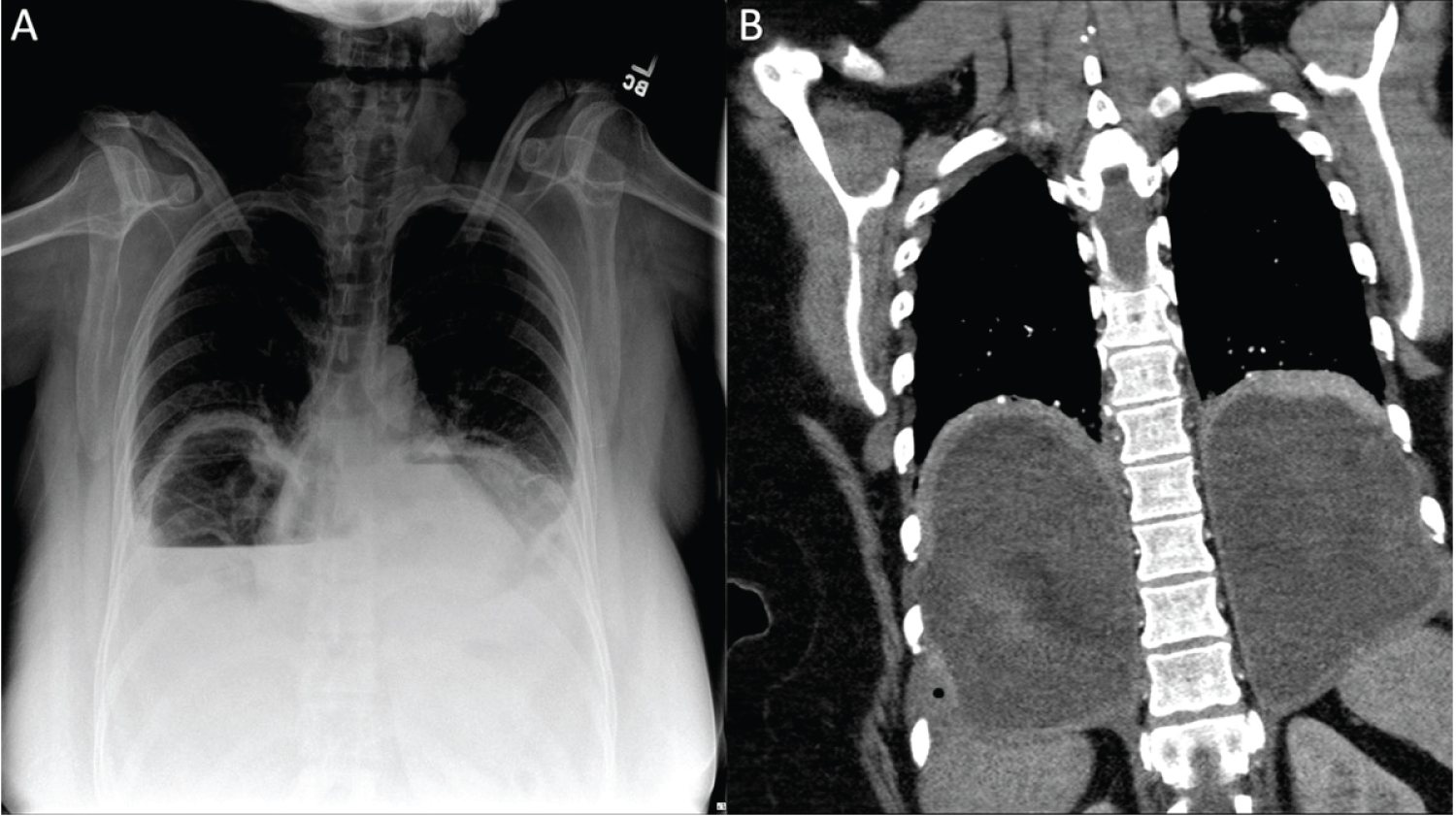

On post-op day (POD) 11, the patient presented to the emergency department with complaints of shortness of breath, chest pain, and dysphagia starting soon after discharge. Vital signs were significant for tachycardia, tachypnea, and normal blood pressure. White blood cell (WBC) count was 29.9 × 103 cells/μL with 28% neutrophil bands. Chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) angiography demonstrated large communicating bilateral empyema crossing the midline through the posterior mediastinum surrounding the distal esophagus without evidence of oral contrast extravasation (Figure 1). Bilateral 14 French pigtails were placed in the interventional radiology suite with evacuation of approximately 1 liter of foul-smelling purulent material which was subsequently sent for culture. The patient was treated with vancomycin, cefepime, metronidazole, and fluconazole for the duration of inpatient stay. An upper gastrointestinal swallow study did not demonstrate abnormal position of wrap, dysfunctional swallowing mechanism, or contrast extravasation. Chest tube fluid analysis showed an amylase of 39 U/L and triglycerides at 21 mg/dL with a serum amylase of 58 U/L and serum triglycerides at 94 mg/dL. Fluid cultures returned with Streptococcus anginosus and Streptococcus and constellatus.

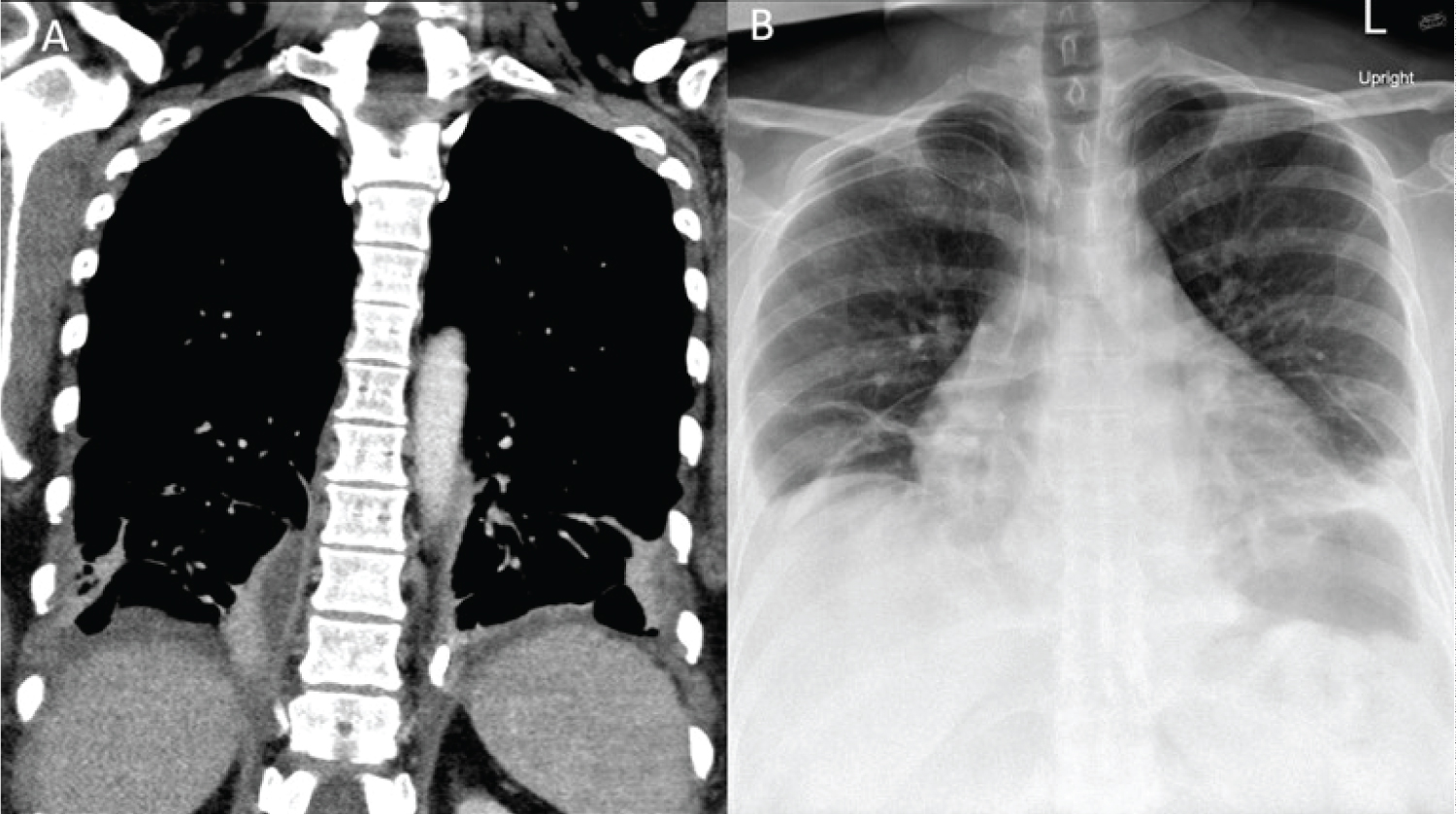

Interval chest CT, obtained on hospital day (HD) 3 demonstrated significantly decreased but incompletely resolved fluid collections with small loculations of pneumothorax on the right. To assist with clearance of residual inflammatory material, fibrinolytic therapy with alteplase was administered into the bilateral pleural cavities via the existing chest tubes. Serial chest X-rays showed overall improvement in empyema's, chest tube output continued to decrease, and patient's dyspnea was decreased with regular incentive spirometry use. Interval CT imaging on HD 10 demonstrated resolution of the empyema and the chest tubes were removed sequentially with hospital discharge occurring on HD 12 (Figure 2).

Discussion

Empyema is a rare complication of paraesophageal hernia repair generally associated with esophageal perforation and subsequent inoculation of pleura with oral flora [3,4]. Bilateral empyema following robotic paraesophageal hernia repair has not been documented. Unrecognized intraoperative esophageal perforations during foregut surgery typically present rapidly with severe inflammatory symptoms. In this case, three etiologies of the bilateral empyema are hypothesized. The first is esophageal perforation during the mediastinal dissection. An occult esophageal injury is possible, although this would likely have resulted rapid clinical deterioration rather than delayed presentation. The second is chylothorax secondary to intraoperative thoracic duct injury. Lab analysis revealed normal triglyceride levels not consistent with chylothorax.

The third and more likely scenario is esophageal injury from bougie insertion. The utilization of bougies has been linked with esophageal perforations, however, these typically present in the immediate post-operative period [3,5]. The esophageal tear in the distal esophagus was visualized and did not appear full thickness. An overlying flap of mucosa hiding a deeper injury is a possibility. The narrowed tip of the bougie could in theory have traveled further than the extent of the visualized mucosal injury. In this case, the patient's fluid collections grew anaerobes and Streptococcus viridians species consistent with upper respiratory or gastrointestinal flora, but imaging revealed no overt signs of esophageal perforation including pneumomediastina or oral contrast extravasation. A small enough injury could allow for mediastinal seeding with oral flora without the more overt and immediate signs of esophageal perforation and severe sepsis.

The purpose of bougie insertion during fundoplication is to prevent excessive narrowing of the alimentary channel from the wrap with resultant dysphagia with the concomitant potential for injury during esophageal intubation [6]. No current standard exists regarding the use or disuse of bougie during fundoplication, and other methods, such as use of EGD as bougie, are practiced. In this scenario, we hypothesize that the bougie was the source of injury, although the clinical course and presentation is not consistent with previously published reports of esophageal injuries from bougie dilation. Empyema following robotic foregut surgery has likely occurred in the past but hesitancy to publish complications has likely influenced the relative scarcity of reporting in the literature.

The robotic platform is a safe and modern approach to foregut surgery. However, one must always be cognizant that the simple, basic steps of procedures, such as bougie insertion, require just as much hands-on experience and skill as operating the robotic platform. We suspect that the etiology of the bilateral empyema in this patient was injury during bougie insertion. Standards regarding the use of bougie or other esophageal dilator during foregut surgery are not available. Should well-performed studies ever be completed, the use of bougies or similar devices may very well be seen as unnecessary. However, without guidelines, anecdotal experience and dogma will continue to be a primary factor in surgeon technique choice. Complications during routine surgery, although potentially rare, require persistent clinical vigilance as well as knowledge of their management by the practicing surgeon.

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Arcerito M, Changchien E, Falcon M, et al. (2018) Robotic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease and hiatal hernia: Initial experience and outcome. Am Surg 84: 1945-1950.

- Melvin WS, Needleman BJ, Krause KR, et al. (2002) Computer-enhanced robotic telesurgery. Initial experience in foregut surgery. Surg Endosc 16: 1790-1792.

- Theodorou D, Doulami G, Larentzakis A, et al. (2012) Bougie insertion: A common practice with underestimated dangers. Int J Surg Case Rep 3: 74-77.

- Edriss H, El-Bakush A, Nugent K (2014) Esophgeal perforation and bilateral empyema following endoscopic esophyx transoral incisionless fundoplication. Clin Endosc 47: 560-563.

- Lowham AS, Filipi CJ, Hinder RA, et al. (1996) Mechanisms and avoidance of esophageal perforation by anesthesia personnel during laparoscopic foregut surgery. Surg Endosc 10: 979-982.

- Patterson EJ, Herron DM, Hansen PD, et al. (2000) Effect of an esophageal bougie on the incidence of dysphagia following nissen fundoplication: A prospective, blinded, randomized clinical trial. Arch Surg 135: 1055-1062.

Corresponding Author

Dr. Peter D Drevets, MD, Department of Surgery, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, 1120 15th Street, BA-4300, Augusta, GA, 30912, USA, Tel: +1-405-473-1093

Copyright

© 2022 Drevets PD, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.