Making Sense out of Pandemic COVID-19 and Public Health Measures: A Message for the General Public

Abstract

Pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread to 213 countries and territories, resulting in 2,883,603 confirmed cases and 198,842 deaths as of April 28, 2020. Even after nearly 5 months in its progress, the COVID-19 outbreak is still seeing incompliant and irrational public responses towards infection control and prevention measures in various countries. Risk communication and public risk perception play a crucial role in the control of epidemics. Although COVID-19-related public education materials are readily available in many trustworthy resources, it seems that the COVID-19 infodemic overwhelms, confuses, and misleads information seekers. One's health literacy and health information-seeking skills, therefore, will influence his/her perception of risk and compliant behaviors towards recommended public health interventions during this pandemic. Given the low World's health literacy rates, enhanced and focused education of the general public deems necessary to slow down the speed of outbreaks, ultimately ending the pandemicity. This review aims to provide minimum essential information for the general public to understand the current pandemic and control measures and proper use of personal protective equipment, thus enabling them to comply with the recommended local health interventions rationally. With improved understanding the general public should be able to take sensible and self-responsible measures in the fight against this pandemic.

Keywords

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), SARS-CoV-2, Epidemic, Risk communication and perception, Infection control and prevention (ICP), Face mask, Personal protective equipment (PPE)

List of Abbreviations

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; PPM: Personal protective measures; PPE: Personal protective equipment; PFE: Particulate filtration efficiency; BFE: Bacteria filtration efficiency; VFE: Viral filtration efficiency; WHO: World Health Organization; CDC: Centers for Disease Prevention and Control; ECDC: European Center for Disease Prevention and Control

Introduction

Pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread to 213 countries and territories, resulting in 2,883,603 confirmed cases and 198,842 deaths as of April 28, 2020 [1]. Along with an increasing number of cases worldwide, incompliant and irrational public responses towards infection control and prevention (ICP) measures have been reported in the media outlets in various countries including those not yet affected by the virus.

Risk communication (the ways and means authorities inform the public about the risk of infection, morbidity, and fatality) and risk perception (public understanding of risk) play a crucial role in the control of epidemics. COVID-19 related public education materials are readily available in many trustworthy resources such as World Health Organization (WHO) [1], Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [2], or European Center for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC) [3]. Nonetheless, COVID-19 infodemic-an overabundance of information including misinformation [4] can overwhelm, confuse, and mislead the information seekers. One's health literacy (the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information to make appropriate health decisions) [5] and health information-seeking skills, therefore, will influence his/her perception of risk and compliant behaviors towards the recommended public health interventions during this pandemic.

The global health literacy level is low; only 14% in mainland Chinese in 2017, merely half of all Europeans in 2013 [6], and 12% of American adultsin 2006 were reportedly health-literacy proficient [7]. In general, people aged 65 and older, who are at higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19 [2], have poor health literacy [5]. Therefore, enhanced and focused education of the general public deems necessary to slow down the speed of outbreaks, which could ultimately end the pandemicity. This review aims to provide minimum essential information for the general public to understand the current pandemic and control measures, thus enabling them to comply with the recommended local health interventions rationally.

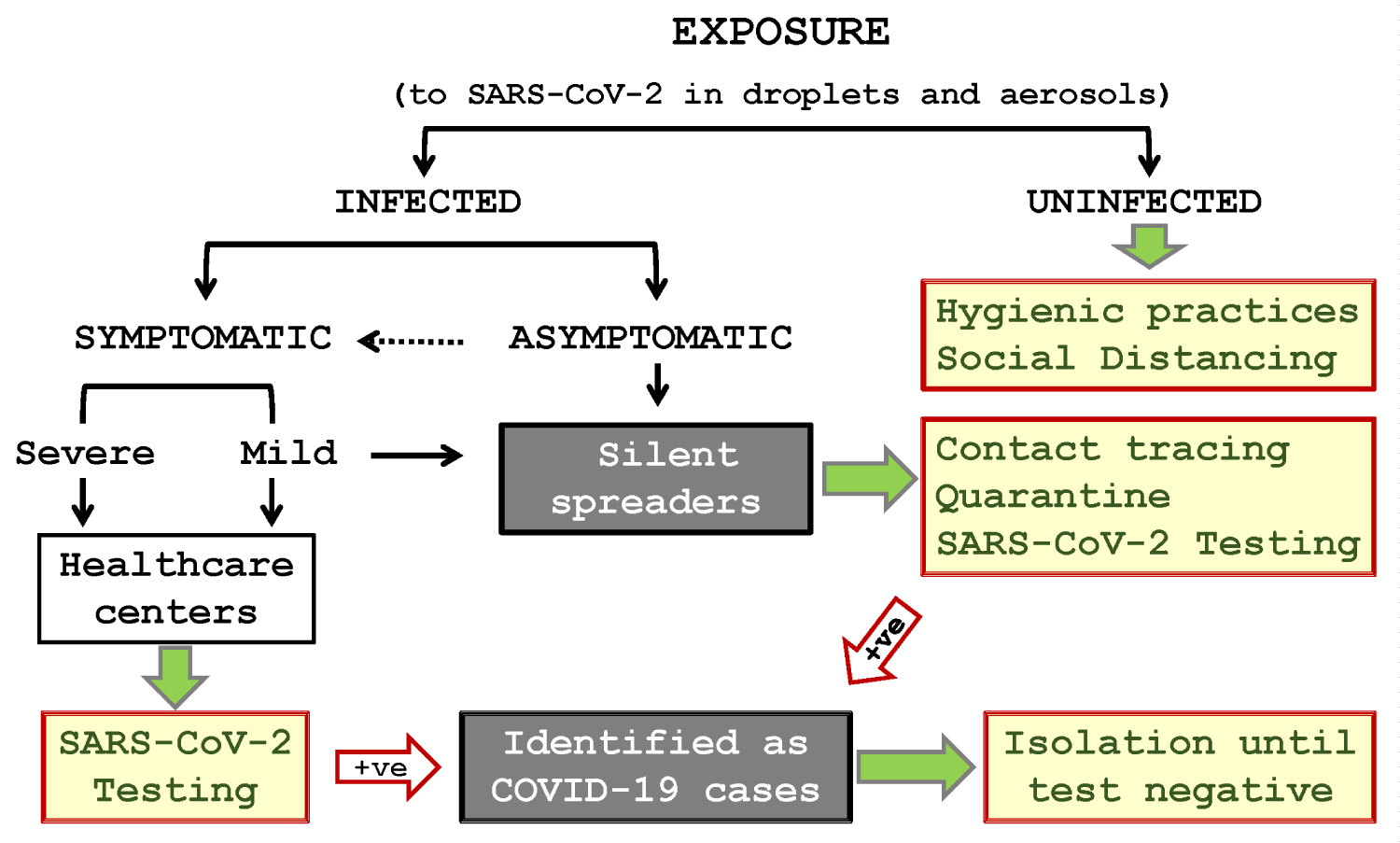

Transmission dynamics and recommended interventions of COVID-19 (Figure 1)

COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). People can be infected from exposure to the virus through the nose, mouth, and eyes. The virus can be present in large droplets (> 5 μm particles) and aerosols (very fine particles of < 5 μm) generated when an infected person speak, cough, or sneeze without protection (i.e., without wearing a face mask or using a tissue paper). The virus-containing droplets on shared objects in public places, such as tables, chairs, door knobs, writing pens, or touch panels, is also a major source of infection via hand-to-mouth self-contamination. Staying in a close proximity (within 1 meter) with an infected person for > 15 min particularly in a poorly ventilated environment can increase the risk of COVID-19 [1-3,8,9].

The exposure will not always result in an infection, but once infected, the person may become symptomatic within 2-14 days of exposure [2], exhibiting fever (< 37.5 °C ~ > 39 °C), cough, fatigue, expectoration, dyspnea, and gastrointestinal symptoms in some cases [2,10,11]. Symptoms are usually mild for most patients but can be severe in about 15% [10,12]. Symptomatic patients who visit healthcare centers will be tested for COVID-19 and if tested positive, they will be treated in isolation until they become test negative. They may be monitored for recurrence for a certain period after discharge. Death rate or case-fatality ratio (CFR)—the no. of deaths divided by the no. of confirmed cases—varies with the calculation methods, case definitions, testing policies, age groups, underlying medical conditions and risk factors, and access to and quality of healthcare in different countries [12]. The available data to date indicates that the death rate of COVID-19 is much lower than that (about 15%) of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) [13], but higher than that (< 0.1%) of seasonal influenza [12].

A fraction of infected people are reportedly asymptomatic and become carriers [14]. The asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic carriers and infected people with mild symptoms who opt not to seek healthcare are silent spreaders, who can transmit the virus to healthy people [15], causing clusters of infection in the community. Therefore, the most crucial epidemic control measure is to identify the silent spreaders by contact tracing; place them under a 14-day quarantine (i.e., the average time between exposure to the virus and the appearance of the first signs or symptoms of COVID) [16]; monitoring them for COVID-19 signs and symptoms; and test their clinical samples for SARS-CoV-2 during and/or at the end of quarantine. Those who become symptomatic or test positive during the quarantine will be isolated and treated accordingly. Cutting the chain of transmission is the goal of infection control.

COVID-19 Epidemic control measures for COVID-19 (Table 1)

There are three epidemiologic terms used to describe the status of infectious diseases in population: Endemic (when there is a perpetual existence of an infection within a particular locality or population), Epidemic or Outbreak (when the number of infected cases goes beyond expected), and Pandemic (when an epidemic has spread beyond its geographic region, affecting a large proportion of the global population). COVID-19 bypassed the endemic phase, as it is a new infection, to become pandemic.

There are also three arms of control measures imposed in epidemics or pandemics like COVID-19, which include containing infected patients, containing silent spreaders, and protecting uninfected people.

Containing patients with COVID-19: It involves testing SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples from the nose (nasopharyngeal swab), throat (oropharyngeal swab), and lungs (sputum) from symptomatic suspected patients. Blood and fecal samples may be tested in some cases [17]. Positive patients are isolated and treated at designated healthcare centers until they become test negative.

Containing silent spreaders: Contact tracing is a measure to identify the contacts—people who had contact with COVID-19 cases thus possibly exposed to SARS-CoV-2—for subsequent quarantine. This measure is extremely important to identify and contain asymptomatic silent spreaders, who could otherwise cause clusters of infection elsewhere, accelerating the speed and magnitude of outbreak. Quarantine is not limited to the contacts within a defined epicenter (the focal point of an epidemic); people arriving from other epicenters regardless of contact history may also be subject to a 14-day quarantine [16], assuring no unknown contacts unidentified. There is a possibility of missing imported positive cases due to longer incubation periods reported with some patients [18].

Protecting uninfected people (from contact with silent spreaders and exposure to the virus): This cannot be achievable without informed cooperation of people in the affected regions.

At the personal level, to prevent exposing self to the virus from silent spreaders, people should develop hygienic practices such as hand washing with soap and water or alcohol hand rub often or when in doubt; avoidance of touching nose, mouth, and eyes with unwashed hands; avoidance of public surfaces; regular disinfection of high-touch surfaces; and avoidance of consuming raw/undercooked foods [1-3]. Spitting and coughing or sneezing without protection in public places—the recognized modes of infection transmission—should be avoided to protect others.

At the community or country level, social distancing is a well-tested strategy to prevent human contacts, involving avoidance of public places and proximity with others. It is most effective when implemented timely and meticulously [19]. Social distancing can be complemented with the closure of schools, restaurants, workplaces, or shops, and banning mass gatherings such as sport, religious, and entertainment events. When the above strategies do not slow down the spread of infection, lockdown (confining or restricting access to people in the epicenter) may be implemented to contain the epidemic. Lockdown may be imposed proactively in the regions not yet affected by the epidemic to prevent importing infection. Travel restrictions or travel bans to and from the epicenters and border closures (sealing off countries or jurisdictions) could be considered in addition to lockdown in curbing the pandemic.

Personal protective measures (PPM) (Table 2)

In any epidemic situation, everyone's responsibility is to protect self and others by sensibly following infection control and prevention measures as recommended by healthcare authorities as follows:

• Staying home and avoiding crowds in public places is the most effective measure to prevent direct or indirect contacts between uninfected and infected people.

• Strict hygienic practices (see Table 2) [20-22] will reduce your risk if you need to be in public places (such as bus/train stations, airports, hospitals) or you have to live with and attend family members who are under home quarantine for suspected COVID-19.

• If you are sick with respiratory symptoms (such as fever, cough, sneezing), wear a face mask, avoid coughing or sneezing without protection, and do hand hygiene often to protect others. Spitting is not acceptable under any circumstances.

An important note on face masks: Face masks are designed differently for healthcare personnel and the general public. While face masks (known as surgical, medical, isolation, dental, or laser procedure masks) and respirators (such as N95, KN95, or FFP2) for medical use are regulated by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [23], face masks for the general public (such as disposable masks and reusable homemade cotton or gauze masks) are not.

The filtration (protection) level of masks is up to their particulate filtration efficiency (PFE), bacteria filtration efficiency (BFE), viral filtration efficiency (VFE), fit to the face, and fluid resistance [23]. The protection characteristics of face masks for the general public are unknown. Therefore, if you need to wear a face mask, choose one that is available readily, but not the ones for healthcare personnel. Homemade (washable) masks are a good choice when disposable masks are in short supply. Those who have a habit of touching face often may consider wearing a face mask [24]. The main message from the global healthcare authorities is that face masks are primarily not for self-protection.

Inappropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE) (Table 3)

Despite concerted international efforts on timely and accurate public communication, lingering uncertainties with COVID-19 pandemic have frightened and confused people especially those with poor health literacy. To complicate the matters further, superstitions, misbeliefs, and misconceptions [25] about preventive measures are instigating irrational public responses and behaviors worldwide. One significant and pressing issue is panic buying and hoarding face masks and using them inappropriately. Misuse of PPE may increase the risk due to a false sense of protection. Table 3 outlines the most common problems with the use of PPE, with face masks in particular [20,21,26].

Conclusions

With the current speed of pandemic, the number of affected countries and infected cases is likely to increase with time. Full public cooperation in the fight against this pandemic with an improved public understanding about the nature of pandemic, associated risks, and intervention measures can be expected only if the concerned authorities could develop communication strategies that are socially and locally appropriate. While keeping aware of widespread misinformation, the general public should also take sensible and self-responsible measures to stay away from the pandemic.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Oxford Clinical Research Project (Grant no. LD0701), the Li Ka Shing Foundation. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Authors' contributions

WBT conceived and designed the study; reviewed the literature, interpreted the data, and wrote and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Dangui Zhang for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Authors' information (optional)

WBT is a Professor of Microbiology and Immunology; the director/head of Clinical Research Unit; the director of undergraduate and postgraduate courses on scientific reasoning in medicine (SRM) and evidence-based medicine; and the director of undergraduate research training (UGRTP) program at Shantou University Medical College.

References

- WHO (2020) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

- CDC (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19).

- ECDC (2020) COVID-19.

- WHO (2020) Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report-13.

- ODPHP (2020) Health literacy.

- WHO (2013) Health literacy-The solid facts.

- US Department of Education (2006) The health literacy of America's adults. Results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy.

- ECDC (2020) Case definition and European surveillance for COVID-19, as of 2 March 2020.

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. (2020) Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med 382: 1564-1567.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382: 1708-1720.

- Li LQ, Huang T, Wang YQ, et al. (2020) COVID-19 patients' clinical characteristics, discharge rate and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol.

- WHO (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report - 46.

- WHO (2003) Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

- Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. (2020) Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA.

- Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. (2020) Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 382: 970-971.

- Linton NM, Kobayashi T, Yang Y, et al. (2020) Incubation period and other epidemiological characteristics of 2019 Novel Coronavirus infections with right truncation: A statistical analysis of publicly available case data. J Clin Med.

- WHO (2020) Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in suspected human cases.

- Leung C (2020) The difference in the incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection between travelers to Hubei and non-travelers: The need of a longer quarantine period. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 41: 594-596.

- Maharaj S, Kleczkowski A (2012) Controlling epidemic spread by social distancing: Do it well or not at all. BMC Public Health 12: 679.

- WHO, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: When and how to use masks.

- WHO (2020) Rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

- World Health Organization (2020) Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care, and in health care settings in the context of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak.

- US FDA (2020) N95 respirators and surgical masks (Face Masks).

- Kwok YL, Gralton J, McLaws ML (2015) Face touching: A frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control 43: 112-114.

- WHO, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Myth busters.

- WHO (2009) Glove use information leaflet.

Corresponding Author

William Ba-Thein, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, and Clinical Research Unit, Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, Guangdong 515041, P.R. China

Copyright

© 2020 Ba-Thein W. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.