Short Review on: Teaching Approach for Head Injury with Epidural Hematoma

Abstract

Background: Epidural hematoma (EDH) is a traumatic accumulation of blood between the inner table of the skull and the stripped-off Dural membrane. EDH results from traumatic head injury, usually with an associated skull fracture and arterial laceration. The incidence of EDH is highest among adolescents and young adults and reported mortality rates range from 5-43%. Therefore, we aim to look into the EDH for both medical students and new physicians face in the recognition, diagnosis and management of these conditions.

Targeted population: EDH patients who are requiring urgent management in the ED, with Emergency Physicians for teaching approach protocol.

Aim of the study: Appropriate identification of EDH patients and management by training protocol to Emergency Physicians. Based on the child's age, site, severity and types of injuries.

Methods: Collection of all possible available data about the EDH at the emergency department. By many research questions to achieve these aims so a midline literature search was performed with the keywords "critical care", "emergency medicine", "principal's Epidural hematoma in different emergencies", "cardiac arrest with Epidural hematoma". Literature search included an overview of recent definition, causes and recent therapeutic interventions strategies.

Results: All studies introduced that initial diagnosis of different emergencies situations for EDH and their interventions therapy are serious conditions that face patients at the emergency departments.

Conclusion: EDH is caused by bleeding in the potential space between the dura and the skull, usually because of traumatic injury. The Clinical manifestations of EDH are highly variable, and include altered consciousness, headache, vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, aphasia, seizures. Head Computed Tomography (CT) is a fast and accurate method for the detection of acute intracranial hemorrhage.

Keywords

Epidural hematoma, Outcome, Emergency physicians, Skill approach

Introduction

Epidural hematoma (EDH) is a traumatic accumulation of blood between the inner table of the skull and the stripped-off Dural membrane. EDH results from traumatic head injury, usually with an associated skull fracture and arterial laceration. The inciting event often is a focused blow to the head, such as that produced by a hammer or baseball bat. In 85-95% of patients, this type of trauma results in an overlying fracture of the skull. Blood vessels in close proximity to the fracture are the sources of the hemorrhage in the formation of an epidural hematoma. Because the underlying brain has usually been minimally injured, prognosis is excellent if treated aggressively. Outcome from surgical decompression and repair is related directly to patient's preoperative neurologic condition [1,2].

In a study of 41 patients with epidural hematoma at a level I trauma center, the patients' age, severity of traumatic brain injury, and neurologic status were the main factors influencing outcome. Two patients died within 24 hours, and 39 patients (95%) survived. Thirty-two patients (78%) showed good recovery at latest follow-up [3,4].

In cases of rare bilateral extradural hematoma (0.5-10%), higher mortality has been reported. Approach to treatment depends on the volume, time of diagnosis, and neurologic deficit level. Simultaneous drainage of bilateral hematomas has been demonstrated to be an effective technique [5].

Scope of the Problem and Rational to this Research Skill Topic

The incidence of EDH is highest among adolescents and young adults. In observational studies, the mean age of patients with EDH is between 20 and 30 years of age. EDH is rare in patients older than 50 to 60 years of age.

Most cases of EDH are due to head trauma caused by traffic accidents, falls, and assaults. Skull fractures are present in 75 to 95 percent of patients. EDH in adults is most commonly (approximately 85 percent of cases) due to arterial injury [6].

The major cause of arterial injury is trauma to the skull base with associated tearing of the middle meningeal artery as it courses through the foramen spinosum, resulting in hemorrhage over the cerebral convexity in the middle cranial fossa. In addition, EDH is occasionally found in the anterior cranial fossa, owing to rupture of the anterior meningeal artery, and rarely due to a dural arteriovenous fistula at the vertex [7].

Mortality rates are essentially nil for patients not in coma preoperatively and approximately 10% for obtunded patients and 20% for patients in deep coma. If treated early, prognosis usually is excellent, because the underlying brain injury generally is limited [8].

Methodology

This section includes Collection of all possible available data about the EDH at the emergency department. By many research questions to achieve these aims so a midline literature search was performed with the keywords "critical care", "emergency medicine", "principals of EDH in different emergencies", "cardiac arrest in EDH". Literature search included an overview of recent definition, causes and recent therapeutic interventions strategies.

So the main aims and outcome of the study: Initial assessment and evaluate of EDH for both medical students and new physicians face in the recognition, diagnosis and management in trauma patients; with cardiac arrest to recognize potentially life-threatening conditions and to convey life-saving treatment so the key note here is that initial diagnosis in suspected cases with rapid emergency interventions (Table 1).

Pathophysiology

Approximately 70-80% of epidural hematomas (EDHs) are located in the temporoparietal region where skull fractures cross the path of the middle meningeal artery or its dural branches. Frontal and occipital epidural hematomas each constitute about 10%, with the latter occasionally extending above and below the tentorium. Association of hematoma and skull fracture is less common in young children because of calvarial plasticity [8].

Epidural hematomas are usually arterial in origin but result from venous bleeding in one third of patients. Occasionally, torn venous sinuses cause an epidural hematoma, particularly in the parietal-occipital region or posterior fossa. These injuries tend to be smaller and associated with a more benign course. Usually, venous epidural hematomas only form with a depressed skull fracture, which strips the dura from the bone and, thus, creates a space for blood to accumulate. In certain patients, especially those with delayed presentations, venous epidural hematomas are treated nonsurgical [10].

Expanding high-volume epidural hematomas can produce a midline shift and subfalcine herniation of the brain. Compressed cerebral tissue can impinge on the third cranial nerve, resulting in ipsilateral pupillary dilation and contralateral hemiparesis or extensor motor response and patients with serious chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other lung disease that prevents sufficient visualization of lung sliding [11].

Epidural hematomas are usually stable, attaining maximum size within minutes of injury; however, Borovich, et al. demonstrated progression of epidural hematoma in 9% of patients during the first 24 hours. Rebleeding or continuous oozing presumably causes this progression. An epidural hematoma can occasionally run a more chronic course and is detected only days after injury [12].

Clinical manifestations

The initial presentation of EDH has a spectrum of manifestations. Severe head trauma may result in EDH with coma, while a lesser injury may produce EDH with only momentary loss of consciousness [13].

In some patients with acute EDH and transient loss of consciousness, there is a so-called "lucidinterval" with recovery of consciousness, followed by deterioration over a period of hours due to continued arterial bleeding and hematoma expansion. This deterioration is typically associated with symptoms such as headache, vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, aphasia, seizures, and hemiparesis [14].

Approximately 7 to 14 percent of traumatic intracranial EDHs occur in the posterior fossa. Such patients may present with elevated intracranial pressure due to venous sinus obstruction. In some instances, cortical blindness is observed secondary to bioccipital dysfunction [15].

Diagnostic evaluation

In the setting of acute head trauma, imaging serves a key role in both diagnosis and appropriate initial treatment.

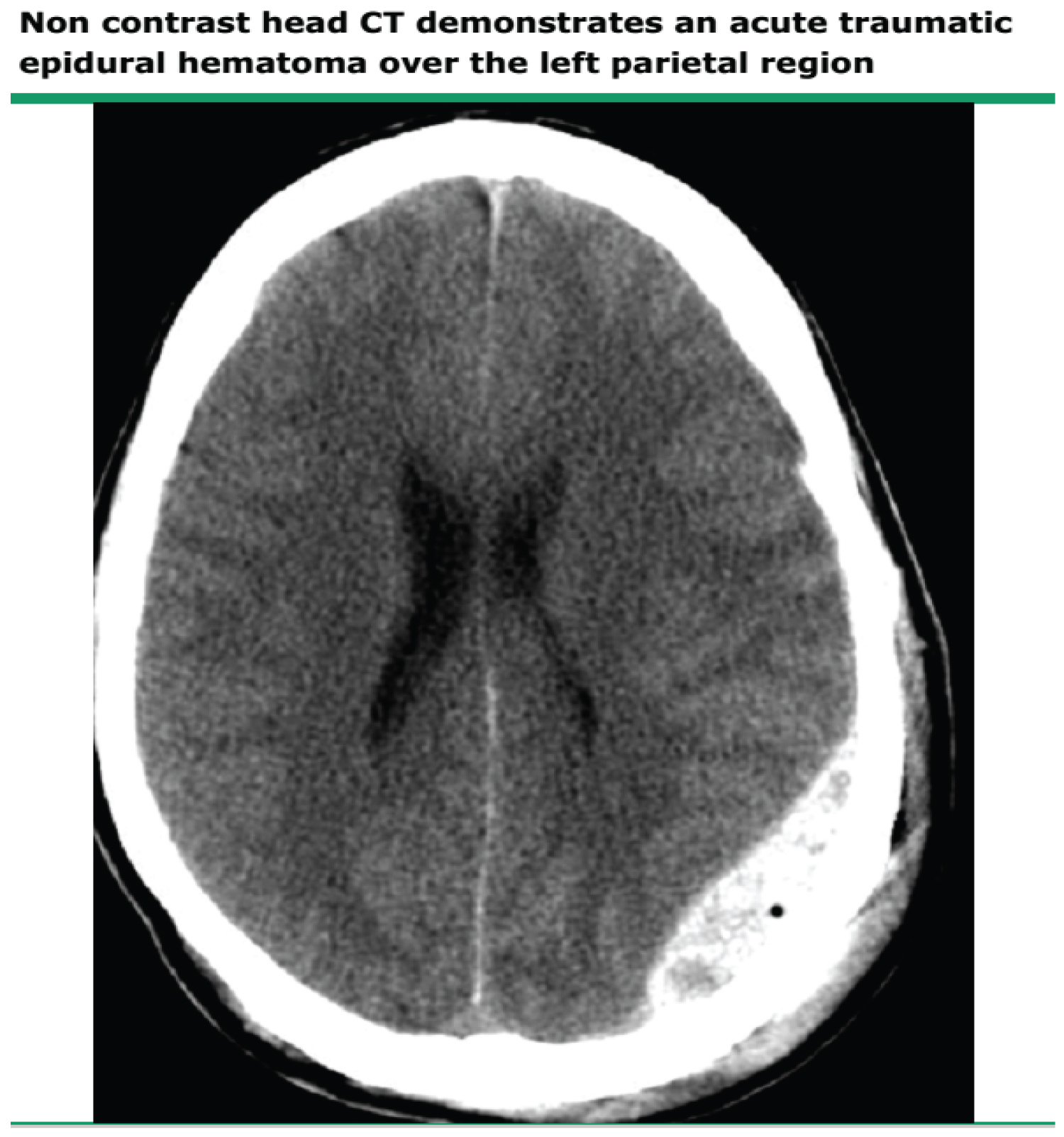

Head CT: Computed tomography (CT) of the head is the most widely used imaging study for acute head trauma owing to its speed, relative simplicity, and widespread availability. Most EDHs are identifiable on CT. Head CT scan shows location, volume, effect, and other potential intracranial injuries (Figure 1) [16].

Findings: Epidural blood produces a lens-shaped or biconvex pattern on head CT because its collection is limited by firm dural attachments at the cranial sutures.

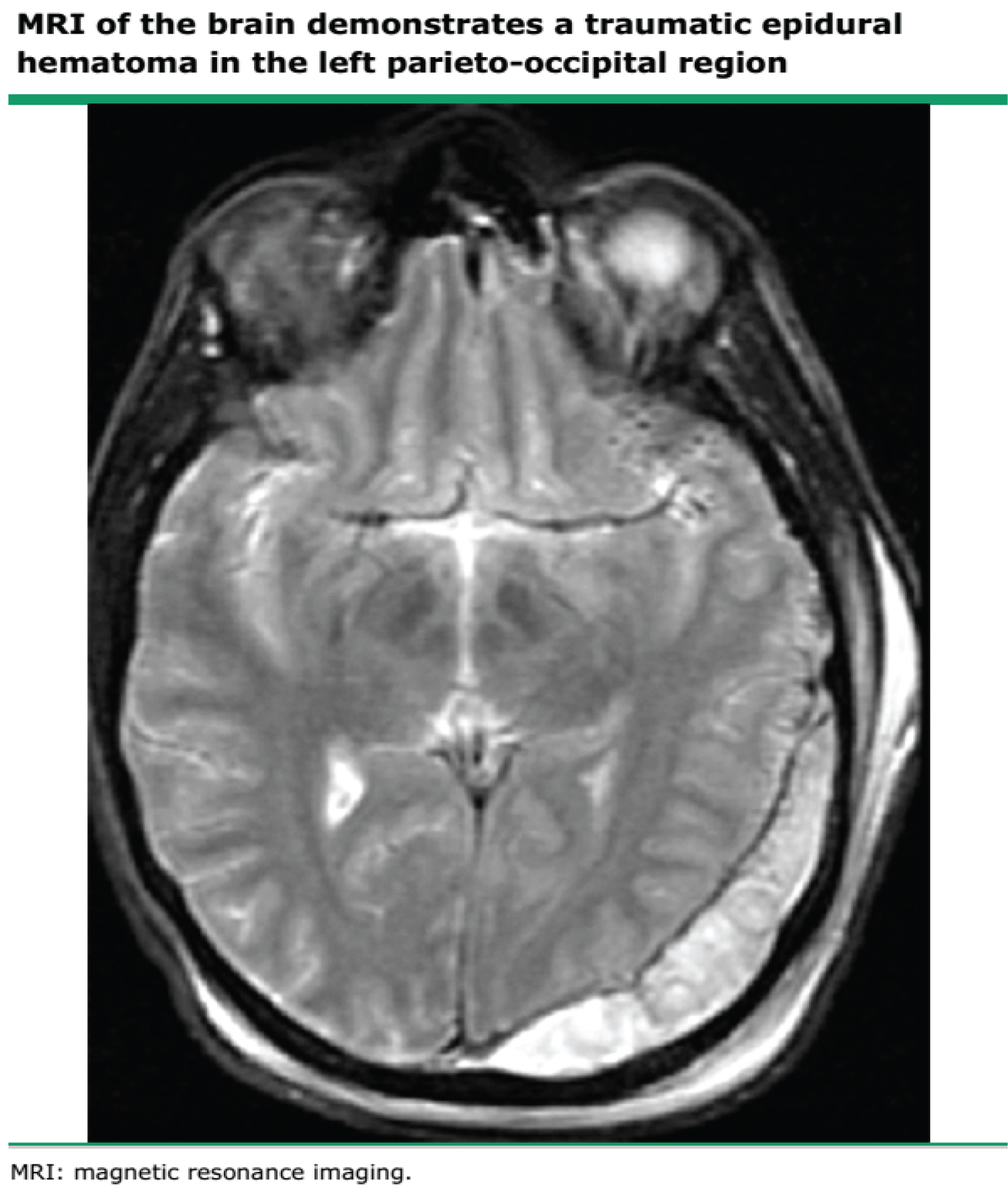

Brain MRI: Although head CT is more widely used, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than head CT for the detection of intracranial hemorrhage. MRI is especially useful in the diagnosis EDH at the vertex. In most centers, MRI is an adjunct to CT in the evaluation of acute head trauma and is used for situations in which there is a strong suspicion for EDH or SDH (ie, suppressed level of consciousness or focal neurologic deficit in the setting of trauma), but no clear evidence of hematoma by CT (Figure 2) [17].

Finding

The MRI signal appearance of EDH and SDH evolves over time in a manner similar to that observed in parenchymal hematoma: The acute clot is hypointense on T2-weighted images due to the presence of Deoxyhemoglobin. Over subsequent weeks, deoxyhemoglobin degrades to methemoglobin, which appears bright on both T1- and T2-weighted images. At several months, only hemosiderin remains, and the clot again becomes hypointense on The T1-weighted images [18].

Angiography

Under unusual conditions, cerebral angiography is indicated for the evaluation of EDH. As an example, EDH located at the vertex can originate from a dural arteriovenous fistula of the middle meningeal artery. In this setting, angiography is necessary to fully evaluate the possibility of an underlying vascular lesion [19].

Management

Emergency department

Establish IV access, administer oxygen, monitor, and administer IV crystalloids as necessary to maintain adequate blood pressure. Intubate using rapid sequence induction (RSI), which generally includes premedication with lidocaine, a cerebroprotective sedating agent (e.g., etomidate), and a neuromuscular blocking agent. Lidocaine may have limited effect in this situation, yet it carries virtually no risk. Premedication with fentanyl may also help blunt a rise in ICP. Intubate after a basic neurologic examination to facilitate oxygenation, protect the airway, and allow for hyperventilation as needed [20].

Elevate head of the bed 30° after the spine is cleared, or use reverse Trendelenburg position to reduce ICP and increase venous drainage [21].

Administer mannitol 0.25-1 g/kg IV after consulting a neurosurgeon if MAP is greater than 90 mmHg with continued clinical signs of increased ICP. This reduces both ICP (by osmotically reducing brain edema) and blood viscosity, which increases cerebral blood flow and oxygen delivery. Fluids must be replaced and hypovolemia avoided [22].

Hyperventilation to partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) of 30-35 mmHg treats incipient herniation or signs of increasing ICP; however, this is controversial. Be careful not to lower PCO2 too far (< 25 mmHg). Perform hyperventilation if clinical signs of increased ICP progress and are refractory to sedation, paralysis, osmotic diuretics, and if possible, CSF drainage. This procedure reduces ICP by hypocarbic vasoconstriction and reduces risks of hypoperfusion and death of injured cells [21].

Phenytoin reduces the incidence of early post-traumatic seizures, although it does not affect late-onset seizures or the development of a persistent seizure disorder.

In a small case series, ED skull trephination before transfer of patients with CT-proven epidural hematoma (EDH) and anisocoria resulted in uniformly good outcomes without complications. Time to relief of intracranial pressure was significantly shorter with trephination than without.

Surgery

Craniotomy and hematoma evacuation is the mainstay of surgical treatment of symptomatic acute EDH. When indicated, identification and ligation of the bleeding vessel must be undertaken. However, there are few data comparing different surgical techniques. Burr hole evacuation (trephination) has been used for acute EDH, and may be lifesaving if access to neurosurgical expertise is limited or likely to be delayed. Open craniotomy affords a more complete evacuation of the hematoma [12].

The decision to perform surgery in patients with acute EDH is based primarily upon the patient's neurologic status, as assessed by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score (Table 2), neurologic examination and pupillary signs, and brain imaging findings (Table 2).

The available evidence, though limited, suggests that surgery should be performed within one to two hours after head trauma, or the onset of neurologic deterioration, for comatose patients with acute EDH and signs of brain herniation.

The head computed tomography (CT) should be repeated serially for patients with acute EDH who are managed without surgery, as there is a high incidence of early hematoma enlargement [15].

Summary and Recommendations

• Epidural hematoma (EDH) is caused by bleeding in the potential space between the dura and the skull, usually as a consequence of traumatic injury. Nontraumatic acute EDH is rare. The incidence of EDH is highest among adolescents and young adults. EDH is rare in patients older than 50 to 60 years of age.

• The source of blood in EDH is most often arterial, but 15 percent of cases are due to venous bleeding. The major cause of arterial injury is trauma to the sphenoid bone with associated tearing of the middle meningeal artery, resulting in hemorrhage over the cerebral convexity in the middle cranial fossa.

• Clinical manifestations of EDH are highly variable, and include altered consciousness, headache, vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, aphasia, seizures, and hemiparesis. Some patients with acute EDH and transient loss of consciousness have a "lucid interval" with recovery of consciousness, followed by deterioration due to hematoma enlargement.

• Head computed tomography (CT) is a fast and accurate method for the detection of acute intracranial hemorrhage. Epidural blood produces a lens-shaped pattern on head CT. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a higher sensitivity than CT and can be useful when diagnostic uncertainty exists. In addition to EDH, head trauma may cause subdural hematoma (SDH), subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral contusion, diffuse brain swelling, and laceration. These injuries frequently coexist following trauma.

• The majority of patients have a good recovery after EDH, but mortality in adults and children is approximately 10 and 5 percent, respectively. Factors associated with prognosis include the severity of neurologic deficits (generally quantified by the Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score), presence of pupillary abnormalities, hematoma volume, the degree of midline brain shift, and the presence and severity of associated trauma.

• Most patients with focal neurologic signs or symptoms attributable to acute EDH require emergent surgical hematoma evacuation to prevent irreversible brain injury or death caused by hematoma expansion, elevated intracranial pressure, and brain herniation. Even in patients who are comatose on admission or have early signs of brain herniation, we recommend urgent surgical hematoma evacuation given the potential for recovery.

• Non-operative management of acute EDH requires close observation and serial brain imaging because of the risk of hematoma enlargement and neurologic deterioration that may require surgical intervention. Thus, we recommend obtaining the first follow-up head CT scan no later than six to eight hours after head injury.

References

- Mayer S, Rowland L (2000) Head injury. In: Rowland L, Merritt's Neurology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA, 401.

- Elbaih AH (2017) Different types of triage. Archives Medical Review Journal 26: 441-467.

- Elbaih AH, Mohammed MA, Ali MA, et al. (2020) Validity of S100B protein as a prognostic tool in isolated severe head injuries in emergency patients. Egypt J Surg 39: 795-806.

- Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, et al. (2006) Surgical management of acute epidural hematomas. Neurosurgery 58: S7-S15.

- Elbaih AH, Elshaboury IM, Ahmed RM, et al. (2018) Validity and prognostic value of serum albumin level in emergency acute ischemic stroke Egyptian patients. Medicine Science 7: 736-744.

- Talbott JF, Gean A, Yuh EL, et al. (2014) Calvarial fracture patterns on CT imaging predict risk of a delayed epidural hematoma following decompressive craniectomy for traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 35: 1930-1935.

- Besenski N (2002) Traumatic injuries: Imaging of head injuries. Eur Radiol 12: 1237-1252.

- Elbaih AH, Abou EA (2020) Approach for emergency traumatic hemorrhagic shock. Sun Text Rev Surg 1: 105.

- Elbaih AH, Basyouni FH (2020) Teaching approach of primary survey in trauma patients. Int J Intern Emergency Medicine 3: 1035.

- Elbaih AH, El-sayed DA, Abou-Zeid AE, et al. (2018) Patterns of brain injuries associated with maxillofacial fractures and its fate in emergency Egyptian polytrauma patients. Chinese J Traumatology 21: 287-292.

- Matsumoto K, Akagi K, Abekura M, et al. (2001) Vertex epidural hematoma associated with traumatic arteriovenous fistula of the middle meningeal artery: A case report. Surgical Neurology 55: 302-304.

- McIver JI, Scheithauer BW, Rydberg CH, et al. (2001) Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as epidural hematoma: Case report. Neurosurgery 49: 447-449.

- Elbaih AH, Elsayed ZM, El Bahrawey MR, et al. (2019) Adherence of emergency physicians to pediatric emergency care applied research network-clinical decision rule (PECARN-CDR) in mild head trauma in emergency patients. Open Scientific Journal of Surgery 1: 43-56.

- Ng WH, Yeo TT, Seow WT (2004) Non-traumatic spontaneous acute epidural haematoma -- report of two cases and review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci 11: 791-793.

- Moonis G, Granados A, Simon SL (2002) Epidural hematoma as a complication of sphenoid sinusitis and epidural abscess: A case report and literature review. Clin Imaging 26: 382-385.

- Elbaih AH (2018) Management and outcome of maxillofacial fractures. Sci Med Central, Journal of Trauma and Care 1: 1031-1032.

- Takahashi K, Koiwa F, Tayama H, et al. (1999) A case of acute spontaneous epidural haematoma in a chronic renal failure patient undergoing haemodialysis: Successful outcome with surgical management. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 2499-2501.

- Shimokawa S, Hayashi T, Anegawa S, et al. (2003) Spontaneous epidural hematoma in a patient undergoing hemodialysis: A case report. No To Shinkei 55: 163-166.

- Elbaih AH, Ahmed OT (2020) Approach for emergency management patients with increased intracranial pressure. J Head Neck Surg 2: 108-112.

- Elbaih AH, Gaashan SM (2021) Teaching review approach for pediatric trauma. ARC Journal of Surgery 7: 13-23.

- (2003) Epidural hematoma. In: Color atlas of emergency trauma. Cambridge University Press, New York, USA, 11.

- David SL (2018) Epidural hematoma clinical presentation. Neurology.

Corresponding Author

Dr. Adel Hamed Elbaih, MD, Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, Emergency Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Flat 3, Building 50, Heraa Street, Garden City Shark, Ismailia, Egypt; Clinical Medicine Science Department, Sulaiman Al Rajhi University, Al Bukayriah, Saudi Arabia, Tel: 00201154599748

Copyright

© 2021 Elbaih AH, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.