Sublingual Compartment Resection for the Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Tongue and Floor of Mouth

Abstract

Purpose

Lingual lymph node (LLN) metastases have been identified in the resection specimens of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the oral tongue and floor of mouth.

They lie above the mylohyoid muscle, and they are excluded from the extent of a discontinuity neck dissection.

The purpose of this study was to determine the frequency of LLN in a series of resection specimens of SCC of tongue-floor of mouth, and discuss its relevance to the philosophy of compartment tongue-floor of mouth resection.

Methods

The authors undertook a retrospective cohort study of the pathology records of 181 patients who underwent wide local excision of the tongue and floor of mouth compartment, in combination with an appropriate neck dissection and free flap reconstruction for SCC.

A descriptive analysis was undertaken of those patients who were identified as harbouring LLN in their resection specimen.

Results

We identified that 7.73% (n = 14) of the study cohort harboured LLN. There were eight males and six females. Their average age was 61.85 (range: 56-72).

The average depth of tumour invasion was 11.02mm (range: 1-20). (n = 12 patients with tumor depth of invasion at least greater than 5 mm)

Three patients had positive LLN (1.65% of total cohort and 21.4% of LLN cohort); one median, and two lateral.

Conclusions

LLN (first echelon nodes) can potentially allow for either the local uptake or direct passage of tumour emboli into the cervical lymph node. Their presence in SCC of tongue-floor of mouth may portend a poor prognostic outlook if they are not resected at the time of primary surgery. Our study lends further support to the argument that the surgical management of SCC of tongue-floor of mouth should include a sublingual compartment resection in combination with an appropriate neck dissection.

Keywords

Lingual lymph nodes, Tongue cancer

Introduction

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) that develop within the mouth, jaw and face, make up a significant proportion of the presentations of Head and Neck cancer (HNC). Cancers of the oral cavity and oropharynx comprise a subset within these. These cancers are the sixth most common cancers worldwide [1,2].

Despite advances in the diagnosis and treatment of HNSCC, there has been little improvement in either overall survival rates or reduction in local recurrence rates. In addition, there is a variable prognosis, even in early stage T1-T2 N0-M0 SCC oral tongue cancer [3,4].

SCC of oral tongue and floor of mouth can be regarded as a biologically distinct entity compared with cancer affecting other oral sub sites. In many cases, these cancers are more aggressive and generally associated with higher rates of metastases.

Anatomically, the tongue is a unique organ comprised of an array of criss-crossing skeletal muscle bundles and endowed with a rich lympho-capillary drainage network. The unpredictability of lymphatic spread of tumour emboli from the tongue has long been recognised by anatomists, researchers and surgeons [4]. Interestingly a number of anatomical studies have confirmed the presence of either small groups of previously under-considered local lymphoid aggregates, deposits of mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), or structurally defined lymph nodes that are intimately associated with the tongue and floor of mouth [5]. The latter are similar to those that are resident within the regional cervical lymph nodal basin. It is well established that, once dissemination to the regional lymph nodes occurs, five-year survival is reduced by as much as 50% [3,4].

An increasing amount of literature has shown that depth of invasion (DOI) has a statistically significant correlation with the development of both local recurrence and regional lymph node metastases [6]. Despite the recent American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC 8th Edition) [7] decision to integrate DOI into the T category, the major limitation that continues to prevail in the diagnostic work up of HNC patients is the inability to pre-operatively identify these prognostically important histopathological risk features from biopsy specimens (for example: Brandwein-Gensler risk factors [8], and the deepest DOI across the entire tumour). This contributes to the effect of stage migration that occurs from the definitive excision.

Therefore, despite the undertaking of an appropriate oncological three-dimensional 'marginal' resection of a local tongue-floor of mouth SCC, we have occasionally observed a catastrophic early postoperative failure. Anecdotally, this seems to occur in the deep tongue or the intervening tissue that can remain between the excised primary site and the neck, especially when undertaken as a discontinuity neck dissection. This phenomenon and its potential association with the observation of the presence of lingual lymph nodes (LLN) in our practice, and as reported in the literature [9-18], underpinned our study.

Our hypothesis was that despite the successful execution of wide local excision, there are idiosyncratic anatomical features of the tongue and its adnexa that predispose to loco-regional failure. Specifically, the presence of positive LLNs that may not be removed as part of the primary tumour resection could potentially be responsible for failure resulting in loco-regional recurrence.

Materials and Methods

Study design and sample

To address the research aspect of this paper, the authors designed and implemented a retrospective cohort study of the pathology records of all patients who had undergone wide local excision of an oral tongue - floor of mouth SCC, involving a neck dissection and microvascular free flap reconstruction.

The study sample was derived from all patients who had undergone resection and free flap reconstruction of HN SCC. The period of study was May 2006 to May2020. All patients had been referred to and attended our regional HNC-MDT, conducted at the Mater-Calvary Hospital, Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia.

All patients were operated on at the John Hunter or Newcastle Private Hospital by the one Maxillofacial Head and Neck Surgeon (GRH), and the one principal microvascular reconstructive surgeon (RLE).

The inclusion criteria were those patients who had:

I. A Primary SCC of T2 or greater of either oral tongue or floor of mouth origin.

II. Undergone a wide local excision of that primary tumour in association with sublingual compartment dissection, with a staging or therapeutic neck dissection

III. Not undergone previous loco-regional radiotherapy.

Data collection

The relevant data required to undertake the study was collected from the patient electronic record system of the hospital network. All patient encounters (both inpatient and outpatient) were recorded on line using the digital medical record (DMR). The relevant data was retrieved from the DMR.

Analysis

A tabulated descriptive analysis was undertaken of the patients who were identified as harbouring LLN in their resection specimens.

Operative management resection technique

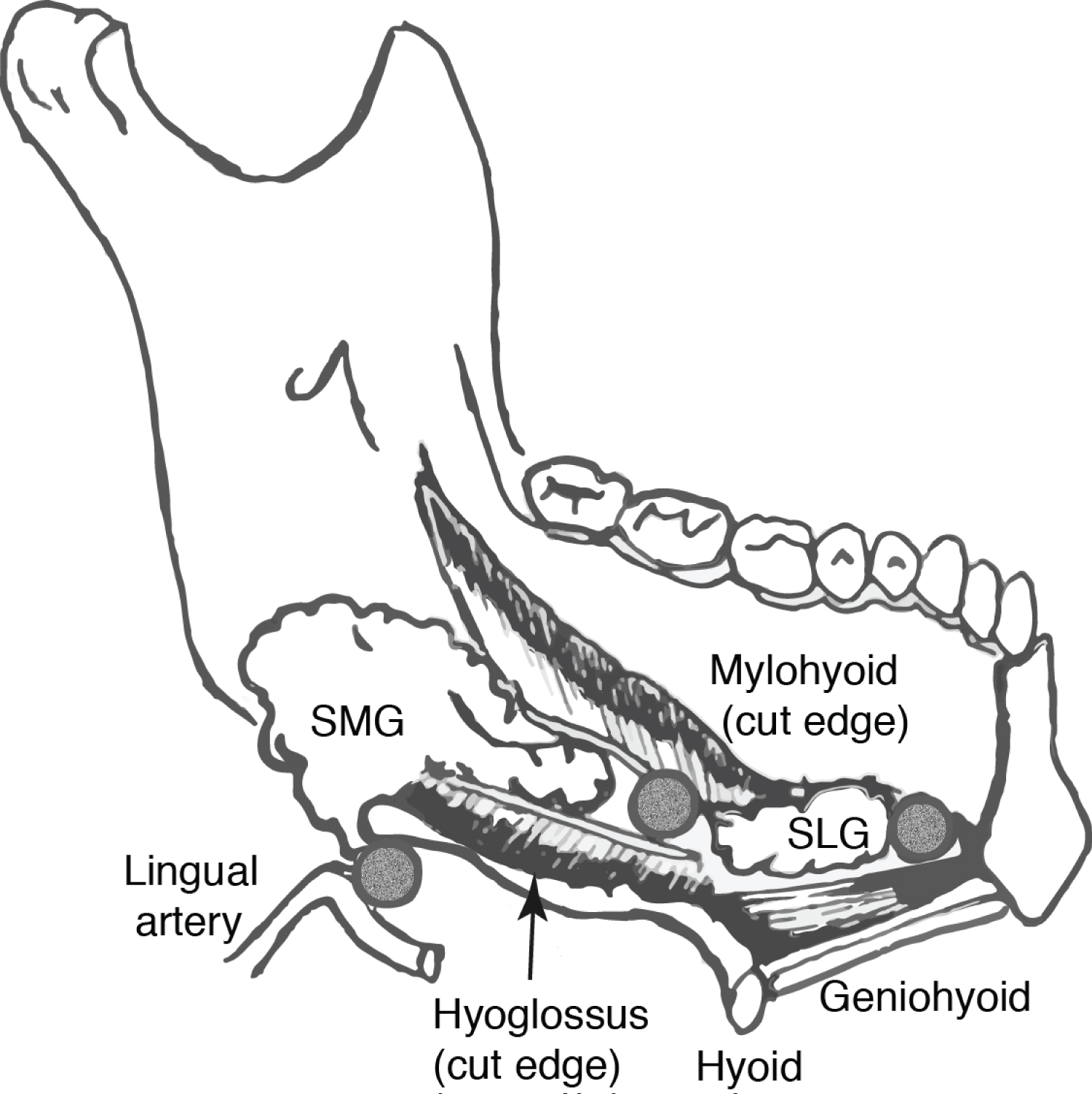

The primary tumour was removed as an extended wide local excision i.e, with a sublingual compartment resection (Figure 1 and Figure 2). This effectively entailed skeletonising the ipsilateral mylohyoid muscle and encompassing both the sublingual gland (SLG) and indicated LLNs. All patients in our series underwent microvascular free flap reconstruction of their respective deficit in order to seal the oral cavity from the neck.

Pathological process

Histopathological examination of the en-bloc resected tongue and floor of mouth compartment was performed after standard preparation. The submitted specimen was sectioned in multiple planes supplemented by cruciate marginal shaves at multiple levels and examined by a designated head and neck pathologist. Specific attention was directed to looking for the presence of lymphoid tissue and any malignant deposits contained therein.

Ethics

The institutional review board granted an exemption in writing as the study was retrospective and the specified surgical treatment was agreed and consented to by the patients following presentation to the Regional MDT. The study was based on a chart review and the relevant pathology was assessed retrospectively. The study adhered to the World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki on medical protocol.

There was no funding, sponsorship, or conflicts of interest to declare.

Results

Two hundred and eighty-seven patients with primary oral cavity SCC were identified from a total of 525 patients who were surgically managed by one extirpative surgeon (GRH) for excision of a primary HNSCC that required a neck dissection, over a 14-year period from May 2006 to May 2020. Of these, 126 tongue, 48 floor of mouth and seven combined lesions gave a total of 181 patients who were included in the study. Fourteen patients (7.73%) harboured LLN in their resection specimens (Table 1). There were eight males and six females. Their average age was61.85 (range: 56-72). Three of these patients (21.4%) were identified as having positive LLN; one had a median LLN and two had a lateral LLN. The average depth of tumour invasion was 11.02 mm (range:1-20 mm). Twelve patients had a tumour DOI greater than 5mm while eight of these had a DOI greater than 10 mm.

Specifically, there were:

I. Two positive L-LLN in each of an N° and N+ neck

II. Four negative L-LLN in N° necks

III. Six negative L-LLN in N+ necks

IV. One positive M-LLN in an N° neck

V. One negative parahyoid-lingual (PH-LLN) in an N+ neck

The relevant literature review has been based on the tabulation of ten isolated case reports (Table 2) [9-18] and seven larger case series. (Table 3) [19-24].

Discussion

Lingual lymph node metastases have been identified in the resection specimens of SCC oral tongue and floor of mouth. The presence of positive LLN that are not removed as part of a conventional wide local excision and discontinuity neck dissection could potentially be responsible for loco-regional recurrence (persistence).The purpose of our study was to calculate the frequency of LLN and the incidence of their involvement in a cohort of patients who had undergone surgical management of an SCC of either tongue or floor of mouth.

The anatomical characteristics of the tongue and for that matter the adjacent conduit of the lingual sulcus (aka floor of mouth) may unfortunately predispose these two structures to tumour involvement outside of the field of conventional wide local surgical excision. That is, it is evident that the primary tumour can invade unhindered into the substance of the tongue and floor of mouth and that resultant tumour emboli can be taken up into the lymph - capillary networks or spread peri-neurally and readily predispose to loco-regional and subsequent distant disease.

Lymphatic system and lymphatic drainage of the tongue-floor of mouth

The lymphatic system consists of a unidirectional vessel network that re-cycles interstitial fluid, protein and waste and, in addition, acts as a conduit for the passage of immune competent cells [25]. In addition to its processing of a wide variety of antigenic challenges (which affords immune competence), it unfortunately also facilitates the dissemination of cancer cells by either infiltration, permeation or embolization.

The structural components that constitutes the lymphatic drainage of the tongue have been well studied over the last 150 years [26-28]. The cumulative results of these studies conclude that the lymphatic drainage of the tongue is structured on a bilayered lympho-capillary network (superficial = sub epithelial plexus and deeper muscular network) that sequentially drain into a pre-collecting and collecting deep fascialsiphon. The fluid is then conveyed into an afferent (pre-nodal vessel) and thereafter via an efferent (post-nodal vessel) as well as via a variety of internodal connections. The final common pathway and return of the filtrate to the venous system is facilitated via either the right lymphatic duct or the (left) thoracic duct. The defined and anastomosing lymph networks within the tongue may or may not respect putative anatomical boundaries, such as the sulcus terminal is and the median sulcus.

Cervical nodes

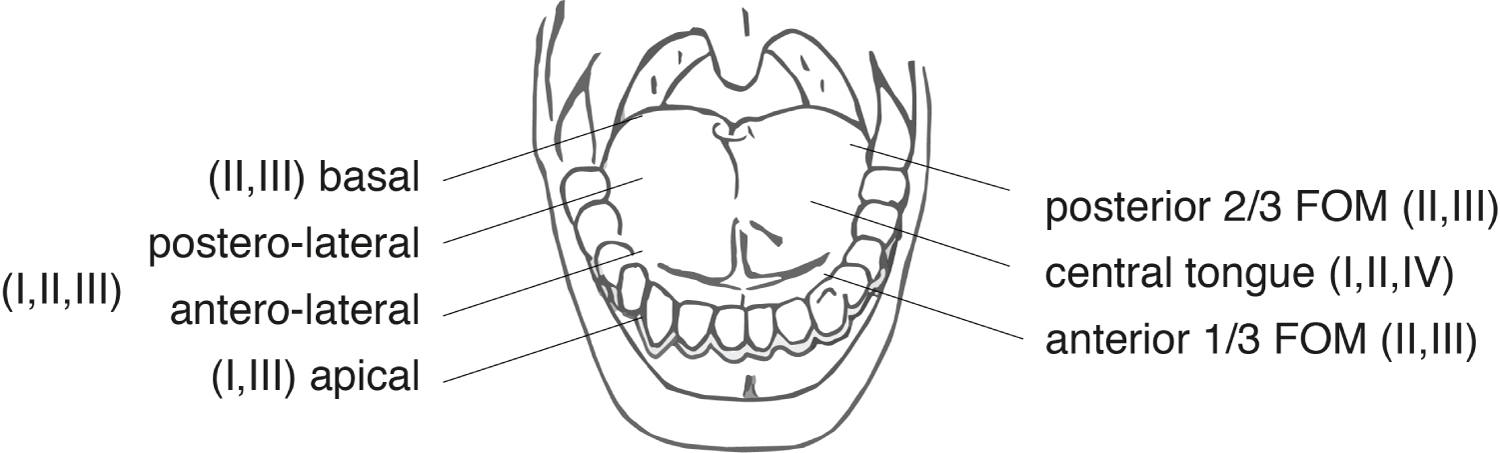

The regional lymphatic nodal system that subserves the head and neck, and in particular its visceral and muco-cutaneous contributions, generally occurs in a relatively predictable and sequential manner, being directed to defined anatomic sub groups within the cervical nodal basin [29-31]. The tongue has been shown to be drained by an organized network of submucosally located collecting lymph vessels and thereafter to the cervical nodal groups indicated in Figure 3.

Sentinel nodes, in-transit/interval/intercalated nodes

The sentinel node is defined as "the first lymph node that receives lymph flow from a primary tumour" [15]. It is therefore reasonably thought to be the node that would most likely contain metastatic carcinoma. The value of surgical sampling such nodes has been well described for breast cancer and melanoma, [15] though not conclusively for muco-cutaneous HN SCC.

There are a group of nodes that can be identified in close contact with lymphatic channels that are located between a primary tumour and the more defined regional draining nodes. They are variously termed In-Transit, Interval or Intercalated lymph nodes. The metastatic involvement of such nodes can be considered to be a cause of local tumour recurrence.

Lingual lymph nodes (LLN): Anatomic and cadavaric studies

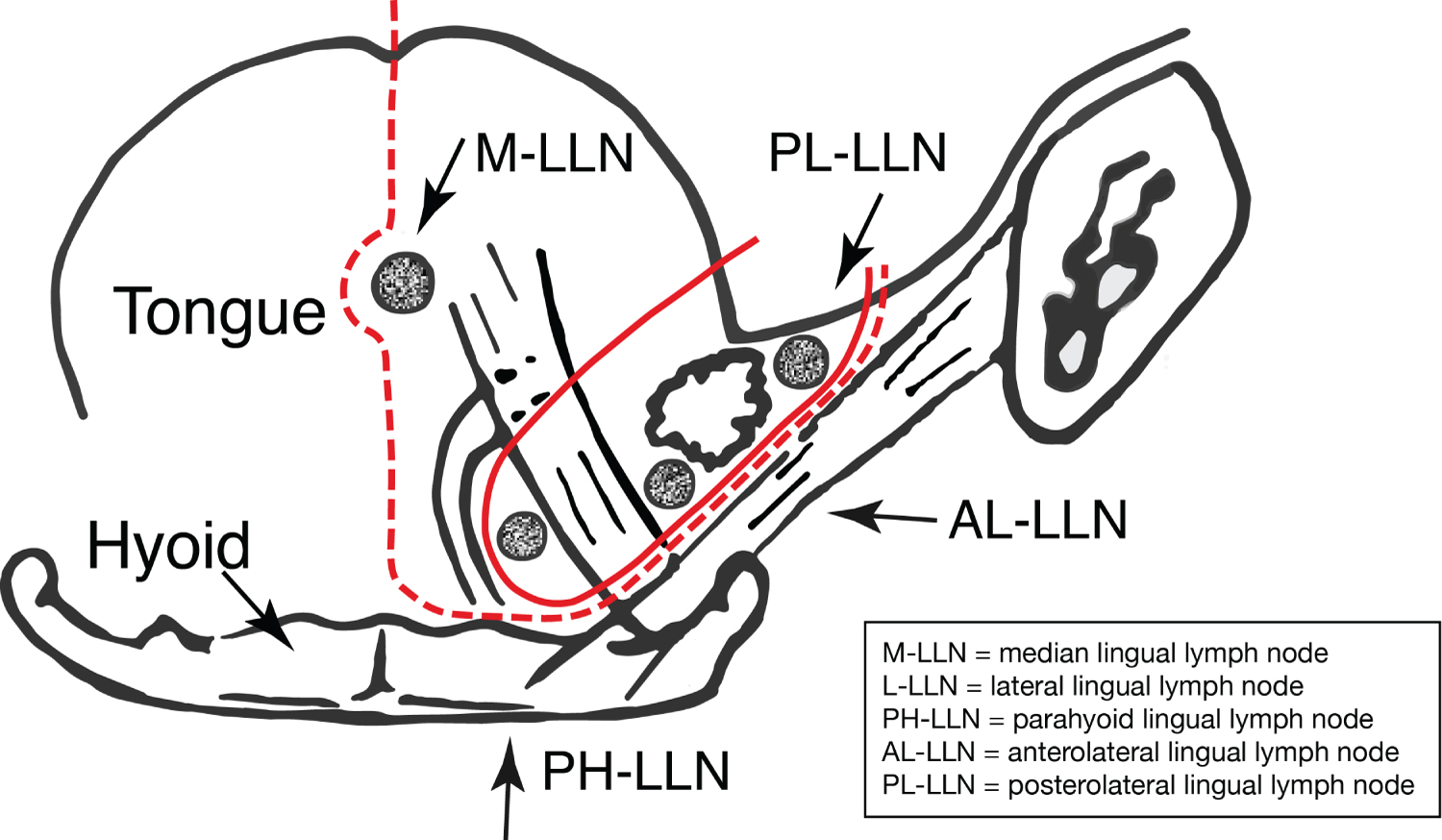

The lingual lymph nodes (LLN) were first described by Rouviere in 1932 [27]. They are considered as In-Transit lymph nodes that can occur interposed between the recognised lymphatic channels of the tongue and floor of mouth and the regional cervical lymph nodes. They have been identified as occurring in three sites:

i) Lateral LLN - are located on the outer surface of the genioglossus muscle (between the tongue and sublingual gland, along the lingual vein and above the lingual nerve) in the paramedian septum.

ii) Median LLN - are located in the median septum.

iii) Deep Lingual node - located at the root of the lingual artery, in the parahyoid region, deep to hyoglossus muscle in the postero-basal midline. Notably, they are superficial to the mylohyoid muscle.

Ananian, et al. [32] undertook an adult (age range: 57-94) cadaveric study to investigate the presence and anatomical disposition of LLNs. They studied 21 formalin fixed specimens and separated each dissected oral cavity into five defined compartments: A: median nodes located between genioglossi and geniohyoidae and two paired (right-left) lateral compartments. BB: [1] parahyoid - nodes located along the lingual artery near to corner of the hyoid; and CC: [1] paraglandular - nodes located in close proximity to the sublingual gland. In the total number of dissected cadaveric specimens (n = 21), they observed n = 0 (0%) median LLN and n = 5 (23.8%) paraglandular - parahyoid LLN. In one of these specimens they identified multiple unilateral nodes (n = 3), which gave a total of 7 nodes in 5 relevant specimens.

Katyama [33] (as cited by Ananian) undertook an investigation of the oral cavity lymphatic system in a group of embryonic and neo natal cadavers and found an incidence of 15.1% median LLN and 30.2% lateral LLN. The difference between the incidence of juvenile and adult LLN reflected in the findings of the two studies may be due to the inherent predisposition that lymph nodes have to undergo involution with age, and in particular to undergo either atrophy, fibrosis or lipomatosis.

Pan, et al. [34] investigated the senile changes that can occur in lymph nodes and identified that connective tissue can infiltrate and efface the entire lymph node architecture. They introduced the term, "transparent lymph node". However, significantly, it is unknown as to whether nodes such as these continue to function as a viable immune competent sub-unit.

As one further observation, in addition to the demonstration of LLN, we have anecdotally periodically noted in our histopathology reviews the presence of small sub-epithelial aggregates of what could be considered as examples of mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). These are most often represented by dense clusters or organoid deposits of lymphocytes and are in agreement with the observations of Ananian, et al. [32]. The relevance and functional significance of these in relation to architecturally structured LLN remains speculative.

Neck dissection: History, evolution, and current status

The late 19th and early 20th centuries bore witness to the seminal publications of Halstead [35] (breast cancer) and Miles [36] (rectal cancer). Each study respectively considered the "centrifugal spiral" and the "zone of upward spread" of tumour cell migration, that can occur from the primary site to the regional lymph nodes. This philosophy was subsequently translated by Crile [37] who proposed a similar comprehensive (regional) lymphadenectomy to manage HNC. This underpinned the further development of neck dissection throughout the remainder of the 20th century. "Radical neck dissection", [38] "Commando en-bloc resection" [39] (ostensibly to capture perimandibular lymphatics, to facilitate mandibular resection when involved and to afford access to the tongue base and pharynx) and "pull through" or "drop out" [40,41] in-continuity operations were all variably applied to oral cancer management throughout the first half of the 20th century.

A return to transoral resection coupled with the identification of site-specific patterns of lymphatic drainage [42,43] engendered the philosophy of elective-selective (and super-selective) as well as modified neck dissections. In recent years, sentinel node (SN) identification (first echelon nodes that may harbour occult disease in the form of individual tumour cells and micro metastases) and excision has been promoted as perhaps an ultra-conservative approach to stage the neck (and address occult disease) in small micro-invasive T1 T2 (N0) oral cavity tumours [10,44].

There remain contentious theoretical problems that need to be highlighted in the application of SN excision for tongue and floor of mouth SCC. The uptake of radio-colloid or radio-isotope may be concordant for SN that are in close proximity to the primary site, and the resultant "shine through phenomenon" that occurs in this situation may make the two indistinguishable [45]. The generally high number of SN that can occur in oral tongue SCC (reportedlya mean of approximately three) [4] combined with their sometimes inaccessible location (i.e,: If they are LLN) may ironically make the undertaking of an elective selective lymphadenectomy an easier and safer proposition [46]. In addition, SN excision may still remain a short fall for both the detection and removal of in transit disease (that which lies between the primary site and the sentinel node).

Steinhart and Kleinsasser [47] have proposed similar mechanisms for the growth and spread of SCC of the floor of mouth. These include infiltration through the sublingual gland (via direct extension or indirect lymphatic permeation) and infiltration through the intrinsic muscles of the tongue or in the potential space between the tongue and the genioglossi musculature.

The idiosyncratic anatomy of the region has provided support for the premise of the undertaking of "compartment (tongue) resection" in association with an in-continuity neck dissection to manage SCC of the tongue and floor of mouth [48]. Calabrese, et al. [49] proposed and researched the technical aspects of undertaking "Compartment Tongue Surgery" resection (CTS) to manage SCC of the tongue. They described CTS as an anatomical approach to resection based on the longitudinal removal of both the primary malignancy and the potential pathways that are likely responsible for its progression. This would include removal of the "at risk territory" that acts as a bridge between the primary and the draining cervical lymph nodes. They investigated 193 patients (50: Marginal resection and 143: Compartment resection). They concluded that CTS was associated with a significant decrease in loco-regional recurrence at 5 years.

A similar resection philosophy was subsequently espoused and investigated by Piazza, et al. [50]. They pre-operatively imaged the tongue and floor of mouth to assess tumour depth of invasion (thickness). They investigated 35 naïve (untreated) and 10 recurrent (previously treated) SCC. The patients were managed by en-bloc removal of the hemi-tongue, ipsilateral floor of the mouth, and muscles comprising the oral pelvis in combination with an in-continuity neck dissection. They concluded that CTS improved the outcome for tumours in the order of 10mm in thickness but only in naïve cases.

Wang, et al. [51] claimed that to date, consensus has not been reached as to whether in continuity or discontinuity neck dissection is more appropriate for treating patients with SCC of the tongue or floor of mouth. They conducted a meta-analysis of eight studies which involved a total of 796 patients and found that in-continuity neck dissection especially for T2 and T3 SCC provided a statistically significant lower incidence of loco-regional recurrence than its discontinuity counterpart.

Our study has some obvious strengths. One surgeon undertook the resective procedure in the same manner, and one pathology group assessed the specimens. The study cohort was homogenous and is comparable in size to series reported in the literature.

The weakness of the study is the reliance on the perseverance of each pathologist in trying to identify all LLN or lymphoid aggregates that may be present in the submitted specimen. Another criticism may be that as pathologists gained experience over the study period they became increasingly interested and adept at identification of lymphoid tissue in the sublingual compartment (this would presumably have led to an underestimation of the incidence of LLNs initially and overall). In addition, we excluded those SCC tongue and floor of mouth that were solely treated by wide local excision and primary closure (the most superficial and limited cancers).

We propose the undertaking of a sublingual compartment resection in combination with an appropriate neck dissection, in particular for anything other than T1 micro invasive SCC of tongue and floor of mouth, is reasonably indicated for at least three reasons:

(i) Preoperative staging is unlikely to accurately predict prognosis (misses Brandwein-Gensler risk factors [8], as well as the deepest invasion across the entire tumour)

(ii) To capture the potential undetectable in-transit disease that would escape standard wide local excision

(iii) To capture the inconstant lingual lymph nodes which would also escape both detection and resection

In conclusion, squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and floor of mouth is an aggressive disease which continues to have a significant failure rate despite adequate 'marginal' clearance. Lingual lymph node (metastases) have been identified in the resection specimens of these malignancies. The presence and metastatic involvement of these LLNs portends a poor prognostic outlook if not removed. We believe that there is justification to undertake a sublingual compartment resection in combination with an appropriate neck dissection for anything greater than T1 micro invasive SCC of tongue/ floor of mouth. The oncological imperative of such treatment enhances the capacity to capture both in-transit lymph vessels and lingual lymph nodes, both of which may harbour occult disease and which may be responsible for local treatment failure if omitted from resection.

Funding

Self funded - not applicable

Conflict of interest

None to declare

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the kind support of Mrs Jacqui Basista and Ms Michelle Donnellan, RN

References

- Warnakulasuriya S (2009) Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 45: 309-316.

- Chaturvedi A, Anderson W, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al (2013) World wide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol 31: 4550-4559.

- Shah J, Patel S, Singh B, et al. (2019) Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology. (5th edn), Elsevier, New York, USA.

- Preis M, Hadar T, Soudry E, et al (2012) Early tongue carcinoma: Analysis of failure. Head Neck 34: 418-421.

- Mashkov OA (1968) Anatomy and topography of lymphatic vessels and regional lymph nodes of adult human tongue (cited from Ananian. Ref 29) Moscow State Medical University.

- Almangush A, Bello I, Coletta R, et al (2015) For early-stage oral tongue cancer, depth of invasion and worst pattern of invasion are the strongest pathological predictors for loco-regional recurrence and mortality. Virchows Arch 467: 39-46.

- Amin M, Edge S, Greene F, et al. (2017) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (8th edn), Springer, New York, USA.

- Brandwein-Gensler M, Teixerra MS, Lewis CM, et al (2005) Oral squamous cell carcinoma: Histologic risk, but not margin status, is strongly predictive of local disease - free and overall survival. AM J Surg Pathol 29: 167-178.

- Ozeki S, Tashiro H, Okamoto M, et al. (1985) Metastasis to the lingual lymph node in carcinoma of the tongue. J Maxillofac Surg 13: 277-281.

- Dutton J, Graham S, Hoffman H (2002) Metastatic cancer to the floor of mouth: The lingual lymph nodes. Head Neck 24: 401-405.

- Han W, Yang X, Huang X, et al. (2008) Metastasis to lingual lymph nodes form squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 46: 376-378.

- Umeda M, Minamikawa T, Shigeta T, et al. (2010) Metastasis to the lingual lymph nodes in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of mouth: A report of two cases. Kobe J Med Sci 55: 67-72.

- Ando M, Asai M, Ono T, et al. (2010) Metastases to the lingual lymph nodes in tongue cancer: A pitfall in a conventional dissection. Auris Nasus Larynx 37: 386-389.

- Zhang T, Ord R, Wei W, et al. (2011) Sublingual lymph node metastasis of early tongue cancer: Report of two cases ad review of the literature. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 40: 597-600.

- Saito M, Nishiyama H, Od Y (2012) The lingual lymph node identified as a sentinel node on CT lymphography in a patient with a CN0 squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 41: 254-258.

- Kaya I, Ozturk K, Turhal G (2017) Sublingual lymph node metastasis in early stage floor of mouth carcinoma. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol 55: 177-179.

- Tomblinson CM, Nagel TH, Hu LS, et al. (2017) Median lingual lymph nodes: Prevalence on imaging and potential implications for oral cavity cancer staging. J Comput Assist Tomography 41: 528-534.

- Eguchi K, Kawai S, Mukai M, et al. (2020) Median lingual lymph node metastasis in carcinoma of the tongue. Auris Nasus Larynx 47: 158-162.

- Omura K, Yanai C, Yamashita T, et al. (1997) Diagnosis and management of lingual lymph node metastasis. Int J Oral maxfac Surg 26: 45.

- Ando M, Asai M, Asakage T, et al. (2009) Metastatic neck disease beyond the limits of a neck dissection: Attention to the para-hyoid area in T1/2 oral tongue cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 39: 231-236.

- Suzuki M, Eguchi K, Ida S, et al. (2016) Lateral lingual lymph node metastasis in tongue cancer and the clinical classification of lingual nodes. J Jpn Soc HN Surg 26: 71-78.

- Woolgar J (1999) Histological distribution of cervical lymph nodes from intra-oral/oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 37: 175-180.

- Jia J, Jia M, Zou H (2018) Lingual lymph nodes in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and the floor of mouth. Head and Neck 40: 2383-2388.

- Fang Q, Li P, Luo R, et al. (2019) Value of lingual lymph node metastasis in patient with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Laryngoscope 129: 2527-2530.

- Margaris K, Black R (2012) Modelling the lymphatic system: Challenges and opportunities. J Royal Soc Interface. 9: 601-612.

- Sappey P (1874) Anatomie, physiologie,pathologie des vaisseaux lymphatiques. Adrien Delahaye Paris FR.

- Rouviere H (1932) Anatomie Des Lymphatiques de L'homme Maissonet Lei. Paris FR.

- Han X, Li J, Pi X (2005) Study on distribution and drainage of lymphatic vessels of tongue. Xua Xi Lou Qiang Yi Zue Za Zhi 23: 400-403.

- Pan W, le Roux C, Levy S, et al. (2010) Lymphatic drainage of the tongue and soft palate. Eur J Plast Surg. 33: 251-257.

- Werner J, Dunne A, Myers J (2003) Functional anatomy of the lymphatic drainage system of the upper aerodigestive tract and its role in metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 25: 322-332.

- Mukherji S, Armao D, Joshi V (2001) Cervical nodal metastases in squamous cell carcinoma of the Head and Neck: what to expect. Head Neck 23: 995-1005.

- Ananian S, Gvetadze S, Ilkaev K, et al. (2015) Anatomic - histologic study of the floor of the mouth: The lingual lymph nodes. Jpn J Clin Oncol 45: 547-554.

- Katyama T (1943) Anatomical study of the lymphatic system of the mouth. J Nippon Dent Assoc 30: 647-677.

- Pan W, Suami H, Taylor I (2008) Senile changes in human lymph nodes. Lymphat Res Biol 6: 77-83.

- Halstead W (1894) The results of operations for the cure of cancer of the breast performed at Johns Hopkins Hospital June 1889 to January 1894. Ann Surg 5: 497-555.

- Miles W (1908) A method of performing abdomino-perineal excision for carcinoma of the rectum and of the terminal portion of the pelvic colon. Lancet 172: 1812-1813.

- Crile G (1905) On the surgical treatment of cancer of the head and neck. With a summary of one hundred and twenty one operations performed upon one hundred and five patients. Trans South Surg Gynecol Assoc 18: 108-127.

- Martin H, De Valle B, Ehrlich H, et al. (1951) Neck Dissection. Cancer 4: 441-499.

- Ward J, Robben J (1951) A composite operation for radical neck dissection and removal of cancer of the mouth. Cancer 4: 98-109.

- Kremen A (1951) Cancer of the tongue; a surgical technique for a primary combined en bloc resection of tongue, floor of mouth cervical lymphatics. Surgery 30: 227-240.

- Ravitch M (1951) Personal communication "pull-through operation" quoted in Ward GE - Robben JO. Cancer 4: 106.

- Lindberg R (1972) Distribution of cervical lymph node metastases form squamous cell carcinoma of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts. Cancer 29: 1446-1449.

- Shah J (1990) Patterns of cervical lymph node metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract. Am J Surg 160: 405-409.

- J den Toom I, Janssen L, Van Es R, et al. (2019) Depth of invasion in patients with early stage oral cancer staged by sentinel node biopsy. Head Neck 41: 2100-2106.

- J den Toom I, Van Schie A, Van Weert S, et al. (2017) The added value of SPECT-CT for the identification of sentinel nodes in early stage oral cancer. Euro J Nucl Med Molec Imaging 44: 998-1004.

- De Cicco C, Trifiro G, Calabrese L, et al. (2006) Lymphatic mapping to tailor selective lymphadenectomy in CN0 tongue carcinoma: Beyond the sentinel node concept. Euro J Nucl Med Molec Imaging 33: 900-905.

- Steinhart J, Kleinsasser O (1993) Growth and spread of squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of mouth. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 250: 358-361.

- Ong H, Ji T, Zhang C (2014) Resection for oral squamous cell carcinoma: A paradigm shift from conventional wide resection towards compartmental resection. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 43: 784-786.

- Calabrese L, Bruschini R, Guigliano G, et al. (2011) Compartment tongue surgery. Long term oncologic results in the treatment of tongue cancer. Oral Oncol 47: 174-179.

- Piazza C, Grammatica A, Montlto N, et al. (2018) Compartment surgery for oral tongue and floor of mouth cancer: Oncologic outcomes. Head Neck 41:110-115.

- Wang H, Zheng Y, Pang P, et al. (2018) Discontinuous versus in-continuity neck dissection in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and floor of mouth: Comparing the rates of locoregional recurrence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 76: 1123-1132.

Corresponding Author

Dr. Gary R Hoffman, MD, PhD, MBBS, MMedSc, MSc, FACS, FRCS, Visiting Medical Officer (Attending Surgeon) and Professor, Oral - Maxillofacial - Head & Neck Surgery, Surgical Services, John Hunter Hospital and University of Newcastle School of Medicine, Lookout Road New Lambton Heights, 2305 NSW, Australia.

Copyright

© 2020 Hoffman GR, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.