Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women

Abstract

The chronic infection HBV is a worldwide public health trouble with high morbidity and mortality. The vertical transmission (pregnancy) has consequences for mother and baby. During pregnancy, cell-mediated immunity is suppressed, possibly because of an increase in adrenal corticosteroids, estrogens, and progesterone, thereby allowing the woman to tolerate the semiallogenic fetus. The characteristics and predictors of postpartum hepatitis flares in women with chronic hepatitis B are Serum Alanine Aminotransferase and Hepatitis B DNA Flares in Pregnant and Postpartum Women.

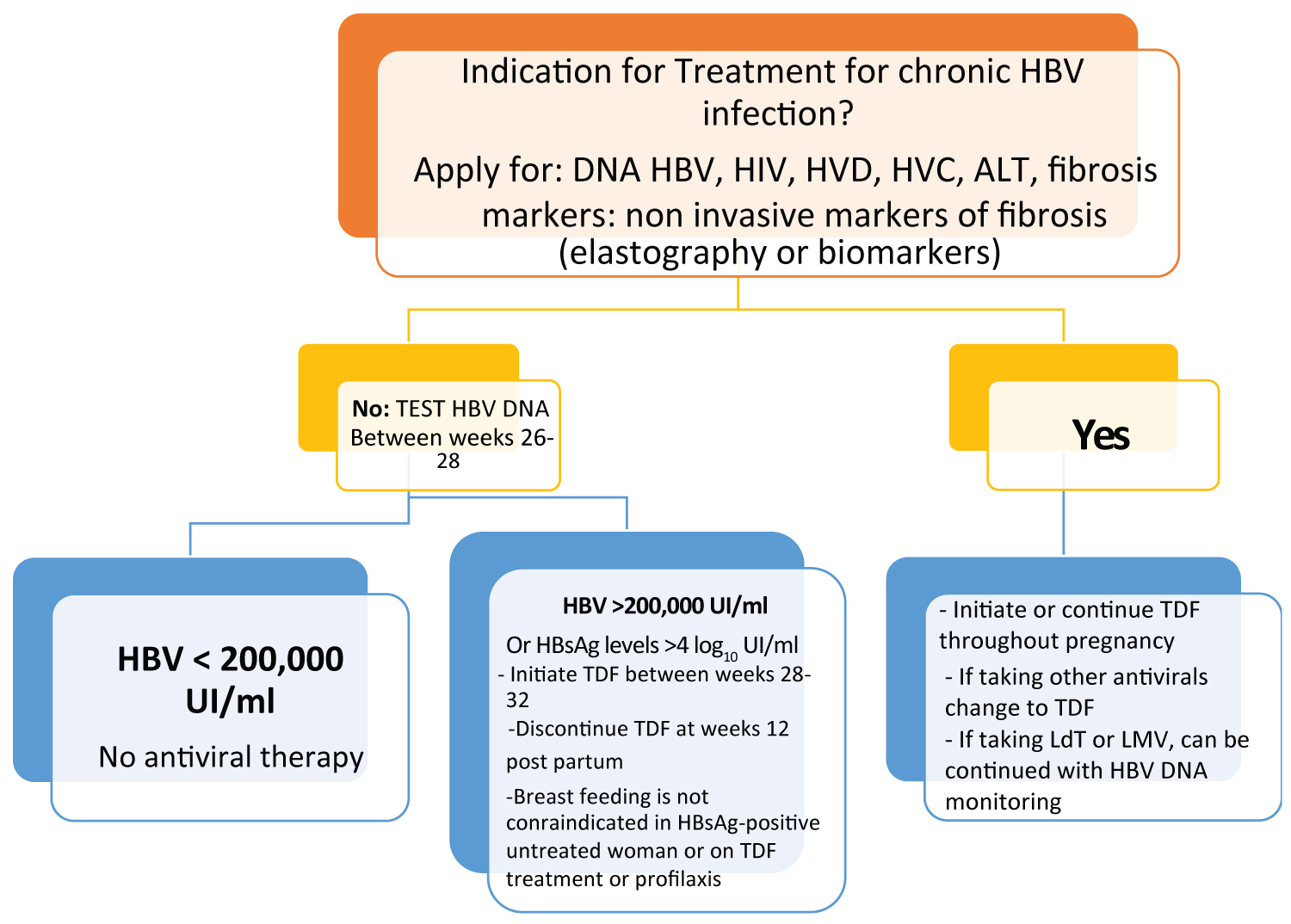

HBV DNA and ALT monitoring every 4-6 weeks during first and second trimesters, as well as every 4 weeks during third trimester, and at postpartum months 3 and 6 should be considered in women with CHB (chronic hepatitis B). Initial assessment requires a determination of the need for treatment of chronic HBV, independent of pregnancy. This will determine the need for treatment during pregnancy and after delivery. For women without active or advanced chronic HBV infection, antiviral therapy can be deferred until post-partum. However, all women need to be assessed in the second trimester for consideration of antiviral therapy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Women with HBV DNA above 200,000 IU/mL warrant antiviral therapy with tenofovir, telbivudine or lamivudine in the third trimester. Tenofovir is the preferred drug during pregnancy.

The management of this population with HBV is important in order to decrease the vertical transmission.

Keywords

Chronic hepatitis B, Pregnancy, Treatment, Vertical infection

Introduction

Infection by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a worldwide public health problem with high morbidity and mortality. Approximately 240 million people have a positive HBVsAg (surface antigen against hepatitis B virus) with variation depending on the locations of endemicity [1].

HBV infection has high relevance in women across the world. There are three levels of prevalence worldwide: High, which is 5-20% countries in Southeast Asia and southern Africa; intermediate, < 5% Asia and Eastern Europe, Australia, and South America; and lower, < 1% North America and Western Europe, with a total of 400 million people [1].

Epidemiology

Despite the effort by international health institutions to implement the vaccine within the mandatory schemes, only 27% of newborns receive a dose of hepatitis B vaccine [1]. In countries with high incidences, such as China and the Asian-American Pacific islands, population barriers persist, such as lack of knowledge, diversity of languages, lack of access and distribution of medicines, as well as medical barriers that prevent adherence to primary prevention [2].

It has two main ways of transmission: The first one is horizontally through sexual contact or by percutaneous infection. It has drawn attention in Asian countries, especially South Korea, for its increase associated with the use of acupuncture as an alternative treatment, in addition to the report of the elevated use of intravenous drugs and the use of tattoos. The second one is through vertical transmission (pregnancy) that has consequences for both the mother and the product [3].

A study in San Francisco revealed that 1.8% of the female population, with a mean age of 37-years old, has hidden HVB infection from the general population and only 2% is known of carrying HIV, none without receiving treatment. Besides, this study identified harmful activities such as toxic consumption of alcohol and the use of recreational drugs [4].

From 2008 to 2012 in the United States, demographic information of 15, 205 women with HBsAg positive were gathered in the cities of New York, Michigan, Minnesota, Florida, and Texas through the Perinatal Hepatitis B Prevention Programs (PHBPPs). The median age was 29 years, the prenatal screening test of HBsAg was taken at a median of 27 weeks pre-delivery, and 11,293 (74.3%) women were of foreign origin. HBeAg(e Antigen Hepatitis B Virus) and/or HBV DNA (Hepatitis B Virus Deoxyribonucleic Acid) testing were obtained for 2,794 (19.8%) pregnancies during four PHBPPs, 0.38% (17,023 of 4,468,773) of prevalence was obtained in women with HBsAg positive and was higher among nonresident women from (2.0% to 8.7%), except from South Asia which was 0.4%, and Africa (3.4%) [5].

In 2013, the prevalence of AgsVHB was 5.49% in a population of pregnant women in China. They divided the population into two groups: Under 20 and over 20-years. They found that the population over 20-years of age had a prevalence of 5.54% compared to the group under 20 years of age (1.30%). Also, they concluded that the most common genotype was the hepatitis C virus (HCV) [6]. Wang carried out a population-based study of women with a desire to become pregnant (15-49-years) in rural areas of China, where low immunity was reported to persist despite including the HBV vaccine in their scheme since 1992. 90% of women with chronic HBV infection were unaware of being carriers and only 7.4% received antiviral treatment, resulting in a very high risk of transmission to their future babies [7].

Its prevalence has been declining in areas of high vaccination, but only 27% of newborns receive a dose of the hepatitis B vaccine. The number of deaths from chronic liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) related to hepatitis B has increased between 1990 and 2013 by 33% (> 686,000 cases worldwide) [1].

In some studies carried out in Africa, for example in Nigeria, there is a prevalence of 4.7% (Osazuwa) and in Uganda of 6.8% (Namirembe), not including patients infected with HIV (Human Inmunodeficiency Virus). In Ethiopia, a study was carried out in 2014 with 421 pregnant patients, reporting a prevalence of HBVsAg of 2.4% in patients aged 18 to 24 years (Dabsu); while in the Sub-Saharan Africa in Wolaita Zone, the prevalence of HBVsAg among pregnant women was 49 (7.3%). Also, the history of multiple sexual partners; surgical procedure, genital mutilation, and teeth extraction were statistically associated with HBV [8].

Natural History of Disease and Immunity in Women

There are several routes of transmission: Intrauterine, childbirth, and the postpartum. Although the virus crosses the placental barrier through some cells, the mode of transmission with the greatest impact is considered to be birth, mainly due to exposure to maternal blood and fluids.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) defined three stages in the natural history of chronic hepatitis B infection):

1. Immune tolerance: This phase lasts between two to four weeks in healthy individuals but it lasts often several decades in those infected during birth or in early childhood. During this phase, active viral replication occurs where the secretion of HBeAg is present and high levels of serum HBV DNA are detected without symptoms and with no significant elevation in serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT). An immunologic response may then develop when HbeAg is secreted, but HBV DNA levels decrease in blood along with the number of infected cells. When it is acute, this stage can last only a few weeks, however, it can become chronic and last over 10 years [9].

2. The second phase is the immunoactive phase, and is defined by intermittent flares of hepatitis demonstrated with an increase in serum ALT, with flares leading liver damage, liver decompensation and even liver cirrhosis [9].

3. In the phase of seroconversion, active viral replication is stopped by the host's immune response. The patients become HBeAg-negative and it can be found anti-HBeAg antibodies while HBV DNA lowers to undetectable levels. Almost 50% have HBeAg negative within 5 years of diagnosis and 70% at 10-years. However, the outcome depends on liver damage or slight levels of HBsAg (which could mean a hidden infection) [9].

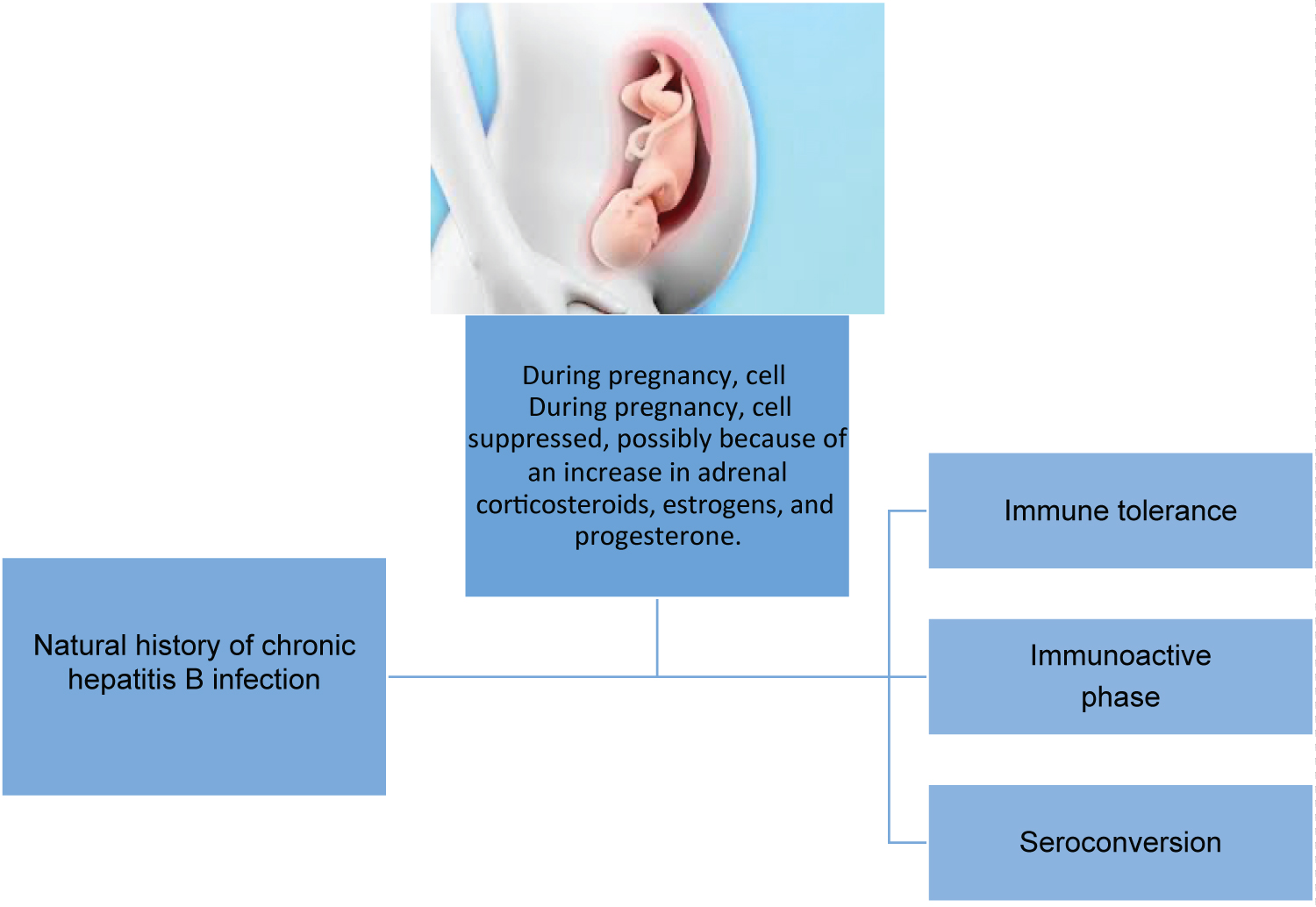

In general, 8-20% of patients with chronic HBV disease have an incidence of progression to cirrhosis in 5 years. The main cause of HCC is chronic HBV in countries with a high prevalence of this infection, such as Korea, China, India, and Turkey. In 40% of chronic patients, HBV infection can progress and increase the risk of HCC [10]. Although, it has been found in its pathophysiology that other factors such as the host gender are related to the progression of the disease. There is a ratio of 2:1 between males and females with cirrhosis because of chronic HBV infection, while the incidence of HCC is three to six times higher in men than women [9]. Also, sexual hormones play an important role in the outcome of this disease between males and females. In a clinical trial, it was identified that female mice had lower levels of HbsAg that were increased after testosterone was administrated. It has been associated that a greater amount of testosterone in males and the male-testosterone supplement affects in different amount the liver androgen receptors in male and female mice, but not because of estrogen inhibitory modulation [11]. During pregnancy, cell-mediated immunity is suppressed, possibly because of an increase in adrenal corticosteroids, estrogens, and progesterone, thereby allowing the woman to tolerate the semiallogenic fetus [12]. See Figure 1 [12].

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical characteristics of hepatitis B in pregnant women are not well defined. The natural history and its clinical traits are mediated by the interactions of the virus with the immune system. Non-specific innate immunity and HBV-specific acquired immunity have an important role in viral clearance. Also, during pregnancy, the immunological tolerance response to the fetus, such as hormonal changes, may have an important role in viral replication.

During the period of 2006-2012, patients with acute HVB were studied and followed in the Infectious Disease Hospital of Jinan. The group of individuals chosen for the study were pregnant and non-pregnant patients which was of the same sex and age at admission, discharge, and follow-up, and their demographic data, clinical manifestations, and results of laboratory tests were compared. During the studied period, there were a total of 618 patients with acute hepatitis B, 22 pregnant patients, and 87 non-pregnant patients. It was observed that, in pregnant patients, the prodromal fever was less common, serum ALT levels were lower, HBsAg has a > 250 IU/mL rate, and serum bilirubin levels were higher than in non-pregnant patients. 18.2% of pregnant patients and 4.6% of non-pregnant patients were still HBsAg positive after a mean of 7 months of follow-up; also pregnant patients had a relative risk of HBsAg positive of 4.6. Finally, pregnant patients had a mean HBsAg seroclearance days of 145.0 while non-pregnant patients had 80.0, showing a delay seroclearance in the first group. Therefore it was concluded that pregnancy might be a possible risk of chronicity following acute HBV infection [13].

In some studies, only HBV DNA levels have been reported and in some, the presence of HBV DNA could not be determined. Although there is a lower seroconversion during pregnancy, HBV commonly not considered a maternal mortality factor. Also, there is no specific association between hepatitis B and the presence of placenta previa, gestational diabetes, or preterm delivery [14,15].

The decrease of corticosteroid levels after childbirth causes fast changes in immunological status from suppression to activation during the postpartum, therefore these changes are consider triggers of hepatitis B flares. It is reported that the incidence of ALT flares varies between 0.3% and 9% among women with chronic HBV without treatment, and it is defined as mild (0.5 times the ULN [Upper Limit of Normal]) or moderate (0.10 times ULN) [16].

Patients with possible postpartum ALT flares could be divided into three subpopulations:

1. Patients with active CHB (Chronic Hepatitis B) who are on antiviral therapy during pregnancy and continue with postpartum treatment (on-treatment flares) [16].

2. Patients who are in the immune tolerance phase and are being treated with antiviral therapy for the prevention of vertical transmission before delivery. These patients discontinue treatment postpartum [16].

3. Patients who are not on antiviral therapy, neither during pregnancy nor postpartum until ALT flares, with antiviral therapy provided after a severe flare [16].

However, 25.45% of postpartum hepatitis B flares have been described in mothers without prior antiviral treatment and are more likely to occur in HBeAg-positive patients. These flares can happen after 3 months of delivery, asymptomatic, and they resolve spontaneously. Although, it is still a problem because there is few data to guide the treatment of flare events and to give supported recommendations. Primarily, ALT flares and exacerbations occur in patients with HBV DNA levels > 5 log10 IU/mL at delivery and ALT level or detectable levels of HBV DNA before delivery are independent risk factors for postpartum ALT events [12,16].

Treatment

It is important to remember that this infection in pregnant patients should be considered in the binomial (mother and child) since it is important to consider vertical transmission in patients with an e positive antigen, that implicates a 70% to 90% risk [17]. To start treatment for HBV infection in pregnant women, it has to be ruled out first other causes of altered liver biochemistry, such as fatty liver of pregnancy, other hepatotropic virus infections, or HELLP (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, Low Platelet Count) syndrome.

Patients of childbearing age without fibrosis can plan a pregnancy and it may be wise to advise to delay therapy until the baby is born. But if they are in advanced fibrosis, it must be a planned pregnancy with the follow-up of the obstetrician and hepatologist [1].

The PegIFNa (Alfa Peginterferon) is contraindicated during pregnancy. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies of LAM (Lamividune), ADV (Adefovir), and ETV (Entecavir) in pregnant women [1]. Reproduction studies in animals and humans with TDF (Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate) and telbivudine (LdT) support that no there is no harm to the fetus due to these drugs [1]; although TDF should be the first choice, because of its better resistance profile and more extensive safety data in pregnant HVB positive [18-20].

It should be considered that the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has classified Entecavir category C in pregnancy, and TDF, as well as tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (TAF) as category B. There are variable schemes but it is recommended to start treatment in all pregnant women with high HBV DNA levels (200,000 IU / ml) or HBsAg levels (4 log10 IU / ml), antiviral prophylaxis with TDF should start at week 24-28 of gestation, and continue for up to 12 weeks after delivery [1].

In some studies, it has been observed that only 33% of patients continue with negative viral loads, and the rest return to their normal levels of viremia when the treatments are suspended [1,21].

Therefore, it is important to individualize the treatment according to the situation of the pregnant patient. In cases where there is no response and the severity is extreme, the patient should be considered for liver transplantation [1].

In November 2016, TAF was approved by the FDA. Its antiviral efficacy is similar to that of TDFbut at a lower dose. Both of them are nucleotides that inhibits reverse transcriptase from HBV pre-genomic RNA (Ribonucleic Acid) [22].

Two phase III, controlled, double-blind clinical trials were made to demonstrate non-inferiority between TDF and TAF, including 873 patients with positive e antigen. Two groups were randomized: One with TAF 25 mg/day and the other with TDF 300mg/day. Both showed normal levels of ALT in 76% vs. 67%, and a decrease of antigen e (14% vs. 12%) in the groups of TAF and TDF [22]. There are no studies with TAF in pregnant patients, so its use is not currently recommended.

In Thailand, a multicenter, double-blind clinical trial was performed in HBeAg positive pregnant women with an alanine aminotransferase level of 60 IU or less per liter. A total of 331 women were enrolled and divided randomly into two groups: The first group (168 women) were given tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and the second (163 women) was given placebo from 28 weeks of gestation to 2 months postpartum. At enrollment, the median gestational age was 28.3 weeks, and the median HBV DNA level was 8.0 log10 IU per milliliter. There were 322 deliveries (97% of the participants) and 319 singleton births, two twin pairs, and one stillborn infant; 1.3 hours was the median time from delivery to the administration of the hepatitis B immune globulin and 1.2 hours median time for the hepatitis B vaccine. Also, the babies received the hepatitis B vaccine at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months. At the start, the (HBsAg) was measured with positive status in the infant and confirmed by the HBV DNA level at 6 months of age. It was found that none of the 147 infants in the TDF group were infected in comparison with 3 of 147 in the placebo group. The rate of adverse events did not differ significantly between groups. The incidence of a maternal ALT> 300 IU per liter after discontinuation of the trial regimen was 6% in the TDF group and 3% in the placebo group [23].

In another study, Nucleo (t) side analogues (NAs) were administered as adjunctive therapy to interrupt the mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of hepatitis B virus (HBV), although the efficacy and safety of this approach is subject to controversy. Another meta-analysis of 9228 mother-infant-pairs in 59 studies was made to evaluate the efficacy and safety of NAs treatment during pregnancy and they studied the differences among distinct agents and initiation trimesters. The observation was that NAs decreased the risk of MTCT, evidenced by the seropositivity HBsAg and HBV DNA in newborns. There were no differences in the efficacy of interrupting HBV MTCT among lamivudine, telbivudine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. NA was more effective when administered from the second than from the third quarterly showed by HBV DNA, but this effect was not seen by HBsAg. There was no higher risk for the newborns with the antiviral treatment started in the second trimester than started in the third trimester evaluated by weight, length, and malformation rate of newborns; therefore it was concluded that the antiviral treatment can be applied in the second trimester without safety concerns. Lamivudine, telbivudine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate are equally effective in blocking HBV MTCT [24]. In HBsAg-positive patients women or on TDF-based treatment or prophylaxis breastfeeding is not contraindicated [1].

The treatment for pregnant women with HBV is summarized in Figure 2 [1,25].

Prevention

Therefore, the instructions of the World Health Organization (WHO) in the use of immunoglobulin and vaccination must be followed. There is limited data but the HBV vaccine is not contraindicated during pregnancy since there is no evidence of fetus damage. It can be applied in any semester of pregnancy and with three applications for the baby: The first one at the moment of birth, the second one month after birth, and the third at 6 months of age [26].

For unvaccinated persons who have been exposed to hepatitis B, it is indicated the HBV immunoglobulin and the vaccine. Immunoglobulin provides passive immunity that lasts for 3-6 months, as long as high concentrations of antibodies from human serum continue. Within the first two weeks after exposure to the virus, it is recommended the application of 500 IU (10 ml) of intravenous infusion, and it can be re-administered every 2 months until seroconversion is obtained [26].

Conclusions

Hepatitis B infection has negative impacts on pregnancy outcomes and leads to higher rates of pregnancy-related complications.

In the setting of pregnancy in general, ALT has been reported to be lower than in non-pregnancy settings with low rates of ALT flare during this period. ALT flares during postpartum have been more commonly described, but reported rates are highly variable (2-62%), as a result of differences in definitions for flare, patient baseline characteristics, and antiviral therapy.

HBV infection should always include treatment for the binomial since it is a maternal disease with vertical transmission to the product. The treatment is based on international clinical guidelines with Nucleus (t) side analogues (NAs) from the second semester and depending on the viral load. Postpartum management of patients who have received antiviral therapy during pregnancy is less challenging because many of them will discontinue treatment if they are still at the immune tolerance phase. Based on previous studies suggesting that the majority of ALT events occur within 12 weeks postpartum.

The risk of severe post-treatment ALT flares is rarely based on a recent RCT (Randomized Controlled Trial) of using TDF on preventing MTCT. In other treatment experience, mothers are often at the immune clearance phase or have significant fibrosis, which requires the continuation of therapy during postpartum; thus, ALT flares could be managed as on-treatment flares. Although spontaneous flares were not associated with clinical decompensation in most patients, severe flares necessitating liver transplantation when salvage antiviral therapy failed have been rarely reported [27].

Primary care is the key to reduce HBV incidence. It is priority to improve health-care providers' knowledge and skills, counseling population, cross-cultural training, reducing the barriers by improving patient and community education, and increasing the support and resources.

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (2017) EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of Hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 67: 370-398.

- Hu KQ (2008) Hepatitis b virus (HBV) infection in Asian and Pacific Islander Americans (APIAs): How can we do better for this special population? Am J Gastroenterol 103: 1824-1833.

- Shin HR, Kim JY, Kim JI, et al. (2002) Hepatitis B and C virus prevalence in a rural area of South Korea: The role of acupuncture. Br J Cancer 87: 314-318.

- Tsui JI, French AL, Seaberg EC, et al. (2007) Prevalence and long-term effects of occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected women. Clin Infect Dis 45: 736-740.

- Walker TY, Smith EA, Fenlon N, et al. (2016) Characteristics of pregnant women with hepatitis B virus infection in 5 US public health jurisdictions, 2008-2012. Public Health Rep 131: 685-694.

- Ding Y, Sheng Q, Ma L, et al. (2013) Chronic HBV infection among pregnant women and their infants in Shenyang, China. Virol J 10: 17.

- Wang Y, Zhou H, Zhang L, et al. (2017) Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B and status of HBV care among rural women who planned to conceive in China. Sci Rep 7: 1-7.

- Bancha B, Kinfe AA, Chanko KP, et al. (2020) Prevalence of hepatitis B viruses and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in public hospitals of Wolaita Zone, South Ethiopia. PLoS One 15: e0232653.

- Wright TL (2006) Introduction to chronic hepatitis B infection. Am J Gastroenterol 101: S1-S6.

- Hwai-I Yang, Sheng-Nan Lu, Yun-Fan Liaw, et al. (2002) Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 347: 168-174.

- Breidbart S, Burk RD, Saenger P (1993) Hormonal regulation of hepatitis B virus gene expression: Influence of androgen receptor. Pediatr Res 34: 300-302.

- Chang CY, Aziz N, Poongkunran M, et al. (2016) Serum alanine aminotransferase and hepatitis B DNA flares in pregnant and postpartum women with chronic hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol 111: 1410-1415.

- Han YT, Sun C, Liu CX, et al. (2014) Clinical features and outcome of acute hepatitis B in pregnancy. BMC Infect Dis 14: 1-7.

- Jonas MM (2009) Hepatitis B and pregnancy: An underestimated issue. Liver Int 29: 133-139.

- Ter Borg MJ, Leemans WF, De Man RA, et al. (2008) Exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection after delivery. J Viral Hepat 15: 37-41.

- Yi W, Pan CQ, Li MH, et al. (2018) The characteristics and predictors of postpartum hepatitis flares in women with chronic hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol 113: 686-693.

- Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Wiersma ST (2012) The risk of perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission: Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) prevalence estimates for all world regions. BMC Infect Dis 12: 131.

- Chen HL, Lee CN, Chang CH, et al. (2015) Efficacy of maternal tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in interrupting mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 62: 375-386.

- Pan CQ, Duan Z, Dai E, et al. (2016) Tenofovir to prevent hepatitis B transmission in mothers with high viral load. N Engl J Med 374: 2324-2334.

- Greenup AJ, Tan PK, Nguyen V, et al. (2014) Efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in pregnancy to prevent preinatal transmission of Hepatitis B Virus. J Hepatol 64: 5-7.

- Maraolo A, Gentile I, Buonomo R, et al. (2018) Current evidence on the management of hepatitis B in pregnancy. World J Hepatol 10: 585-594.

- Lee HM, Banini BA (2019) Updates on chronic HBV: Current challenges and future goals. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 17: 271-291.

- Jourdain G, Ngo GHN, Harrison L, et al. (2018) Tenofovir versus placebo to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 378: 911-923.

- Song J, Yang F, Wang S, et al. (2019) Efficacy and safety of antiviral treatment on blocking the mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus: A meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat 26: 397-406.

- Zhou K, Terrault N (2017) Management of hepatitis B in special populations. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 31: 311-320.

- World Health Organisation (2015) Guideline for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection.

- Bzowej NH, Tran TT, Li R, et al. (2019) Total alanine aminotransferase (ALT) flares in pregnant North American women with chronic hepatitis B infection: Results from a prospective observational study. Am J Gastroenterol 114: 1283-1291.

Corresponding Author

Maria del Rosario Herrero-Maceda, Gastroenterology Section, Central Military Hospital, Ring Road, Blvrd. Manuel Avila Camacho, Militar, Miguel Hidalgo, 11200 Mexico City, Mexico; Gastroenterology Specialization Course of the Military School of Health Graduates, Army and Air Force University of Mexico, Batalla de Celaya 202, Lomas of Sotelo, Militar, Miguel Hidalgo, 11200 Mexico City, Mexico.

Copyright

© 2020 Herrero-Maceda MR, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.