Epidemiological Profile of Cervical Cancer in Bahrain (2005 To 2015)

Abstract

Background

The objective of this study is to analyze the trend of cervical cancer in Bahrain over a 10 year period (2005 to 2015) with the aim of gaining insight into changes in the presentation of cervical cancer.

Methods

This is a cross sectional study in which we analyzed all cervical cancer cases that are registered in Bahrain cancer registry between the period of 2005 and 2015 for their epidemiological and clinical profile.

Results

A total of 165 cases were included and analyzed. The mean (SD) and median age of women at diagnosis during this 10-year period are 49.41 (12.57) and 49 years respectively. Almost 60% of the cases are for Bahraini and 40% for non-Bahraini women. Squamous cell carcinoma (43.6%) is the most common type of cancer followed by adenocarcinoma (17%). Surgery was the treatment of choice in 42.4%. Only 33.3% have received radiotherapy, and 32.7% have received chemotherapy. Forty-two patients out of 165 (25.5%) died because of the cancer itself.

Conclusion

The study findings revealed important implications to the formulation of new healthcare strategies and policies, particularly in regards to cervical cancer screening and introducing the HPV vaccine into the immunization schedule.

Keywords

Cervical cancer, Bahrain, Epidemiology, Cancer registry, Cervix

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most prevalent cancer among females. In 2012, the global incidence rate exceeded 500,000, and the worldwide mortality rate was estimated to be 266,000. It affects women at younger ages compared to other types of tumors and thus has a tragic impact on their lives. The burden of the disease is higher in developing countries, particularly in Africa, where the prevalence rate is the highest. The mortality rate is also higher in developing countries compared to developed countries [1]. The geographical variation that is depicted in the prevalence of cervical cancer is associated with differences in the provision of health services, in particular, screening services, which are important for early detection. In addition, the prevalence of the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is the most common cause of cervical cancer, and the utilization of the HPV vaccine differ between regions, and thus contribute further to the variation.

In the Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) states, cervical cancer is the tenth most common cancer. The highest incidence rate is in Qatar, followed by Bahrain, whereas the lowest incidence rate is in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [1]. In 2012, the annual crude incidence rate of cervical cancer was estimated to be 4.3 per 100,000 in the Kingdom of Bahrain, making cervical cancer the third most common cancer in women of all ages. The annual local incidence rate is estimated at 22 cases, while the annual deaths from cervical cancer are estimated at 5 cases [2]. The population of women in Bahrain at risk of developing cervical cancer is estimated at over 379,000 [3]. This includes women whose age is above 15-years-old. Screening for cervical cancer in the Kingdom of Bahrain is opportunistic with a coverage rate of 43.1% [3].

The Human papilloma virus and related diseases report established by the HPV information centre has shown that cervical cancer is the third most common cancer among women aged 15 to 44 years in Bahrain [3]. For the same age group, the report has shown that cervical cancer is the eighth most common in Saudi Arabia, the fifth most common in Oman, and the sixth most common in Kuwait [3].

The age standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of cervical cancer in Bahrain was 5.9 in 2017 [3]. This is lower than the world's ASIR of cervical cancer at that year, which was 14.0, and lower than that of UK (9.6), and Northern Ireland (8.8) [3,4]. However, it is higher than the ASIR in other gulf countries at the same year, like Kuwait (4.0), Saudi Arabia (2.7), and Oman (5.3) [3].

Cytology is the mainstay for primary cervical cancer screening in Bahrain. It is performed by the Papanicolau smear (Pap smear or Pap test), which is the most common screening test used for cervical cancer worldwide. Other alternatives for screening include HPV DNA testing and visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) [3,5].

Despite the documentation of the relevant data under the national cancer registry in Bahrain, the epidemiological profile of cervical cancer is not adequately studied. Staging and grading of cervical cancer are fundamental for developing a treatment plan, and determining disease prognosis. Hence, we sought to study the epidemiology of cervical cancer given the significance of the findings in setting a health policy and in creating a framework for public health action, particularly in terms of directing public health interventions.

Methods

Study design

Cross-sectional study.

Sample size

All registered cases of cervical cancer in Bahrain Cancer Registry between 1st January 2005 and 31st December 2015 were included.

Data collection

The data was obtained from Bahrain cancer registry, and included the time period between 1st January 2005 and 31st December 2015. The collected data in the study included clinical data related to the cancer like morphology, stage, grade, basis of diagnosis, treatment and cause of death, and sociodemographic data related to the patients like age and nationality. The data collected was of both Bahraini and non-Bahraini women.

Bahrain Cancer Registry (BCR) is a national system of population-based data that provides statistical data that covers all of the residents in the Kingdom of Bahrain, both Bahraini nationals and Non-Bahrainis. To ensure reliability, the data is assessed for duplication and consistency with the use of CanReg4 and the cases are matched to the unique personal identification number of the residents in the country. The data collection process is also very extensive and closely monitored. Cancer notification by physicians is mandatory as per the law, and an electronic notification form is made available in all healthcare facilities. Furthermore, the registrars of the BCR engage actively in data collection by making visits to collect data, and an outpatient registry at Salmaniya Medical Complex follows residents whose diagnoses are made abroad and thereby allows for the extraction of data from their medical records. Hence, underreporting is minimized [6].

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. Frequency distribution and incidence tables are generated using the CanReg4 program. Statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software.

Results

Sociodemographic

165 cases of cervical cancer were registered in Bahrain cancer registry, from 2005 to 2015. The mean (SD) and median age of women at diagnosis during this 10-year period are 49.41 (12.57) and 49 years respectively, with the lowest age being 24 years, and the highest being 90 years. The highest incidence of cases was seen in the age group 45 to 54 (32.1%) followed by the age group 35 to 44 (29%) Table 1.

Around 59.4% (98) of the registered cases are for Bahraini women while 40.6% (67) are for non-Bahraini women. Majority of the women are married (102, 61.8%), 24.2% (40) are single, 4.2% (7) divorced, 7.9% (4) widowed and the rest 1.8% (3) are of unknown marital status. Table 2 shows a summary of the sociodemographic data of patients with cervical cancer in Bahrain.

Clinical characteristics of the tumor

Table 3 shows that squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of cervical cancer (86, 52.1%) followed by adenocarcinoma (41, 24.8%). Most of the tumors (126, 76.4%) are localized to the cervix, with the majority being at an invasive microscopic stage (125, 75.8%), rather than in situ (1, 0.6%). Only (25, 15.1%) of the cases presented with regional or distant metastasis. About one third of the cases (48, 29.1%) are grade 2 tumors, which is moderately differentiated cancer, and about a quarter of the cases (42, 25.5%) were poorly differentiated and 36.4% (60) are of unknown grade.

Out of the 165 cases, 157 (95.2%) were diagnosed by histology. Only 7 (4.2%) of the cases were diagnosed by screening, whether by cytology or hematological testing. The rest of the cases (1, 0.6%) were diagnosed with clinical investigations like ultrasound.

Table 4 shows that surgery was the treatment of choice in 42.4% (70). Only 33.3% have received radiotherapy, and 32.7% have received chemotherapy. One patient out of the 165 cases has received hormonal therapy. Forty-two patients out of 165 (25.5%) died because of the cancer itself.

Discussion

This study described the epidemiological profile of cervical cancer in Bahrain in a 10-year period.

The mean (SD) and median age of women at diagnosis during this 10-year period are 49.41 (12.57) and 49 years respectively. Almost 60% of the cases are among Bahraini and 40% among non-Bahraini women. The mean age of cervical cancer patients in our study was 49 years with the highest incidence found in patients aged 35 to 45 and 45 to 55-years-old. This is lower than the mean age of cervical cancer patients in Morocco (52 years) [7] but higher than UK where the highest incidence rates were found in those aged between 25 to 29 years [4] and higher than the United States where 78% of the cervical cancer cases were diagnosed in women aged 30-39 [8]. Although 24% of the sample were single, one should not that this does not imply abstinence from sexual relationship putting in mind that almost 40% of the sample is non-Bahraini with a wide range of cultural and religious beliefs.

The results have shown that the percentage of patients presenting with squamous cell carcinoma (52.1%) was the highest compared to other types of cervical cancer. This is in agreement with international data in which squamous cell persistently stands out as the most common type of cervical cancer followed by adenocarcinoma [9].

Consistent with the literature, the majority of the cases (75.8%) are invasive and localized to the cervix [10]. However, more than half of the cases presented either with moderately differentiated or poorly differentiated cancer (29.1 and 25.5 respectively). One of the possible causes for this advancement in the presenting stage and grade of the cases could be the opportunistic as opposed to population based screening program of cervical cancer in Bahrain.

The implementation of routine population based cervical cancer screening in countries has led to significant reduction (≥ 50%) in the rates of cervical cancer worldwide [5,11]. In Bahrain, cervical screening is usually offered to married women when they present for postnatal checkup, and as it is an opportunistic program, patients are not actively invited to get screened, which keeps it highly dependent on the patients' decisions and the frequency of their encounter with healthcare providers. The estimated coverage of screening in Bahrain for those aged 30 to 65 years was 43.1% in 2017 [3]. Thus, a very low percentage of the localized cervical cancer lesions (0.6%) were identified as in-situ, which is non-invasive cancer that did not cross the anatomical barriers, and is not at risk of metastasis.

In addition, HPV vaccination has not yet been introduced to the national immunization schedule as a primary prevention strategy for cervical cancer in Bahrain. It is only available in the private health care sector, and is intended to prevent cervical and genital lesions caused by the HPV virus. However, it does not provide immunity against all HPV types. A study about the impact of HPV vaccination across the world has shown that implementing the vaccine as a prevention strategy caused a significant reduction in high coverage countries like Australia, and low coverage countries like the United States [11].

A study assessing the prevalence of human papillomavirus types among women in Bahrain revealed an HPV prevalence of 9.8%. The most prevalent HPV types according to the study were HPV-52, HPV-16, HPV-31, and HPV-51 [12]. One should note that the samples were taken from women attending the postnatal clinic with the majority exhibiting normal cytology.

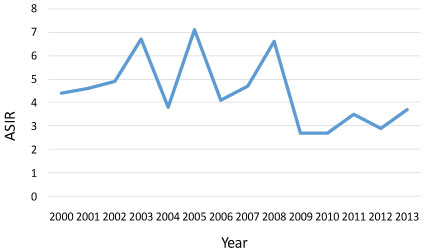

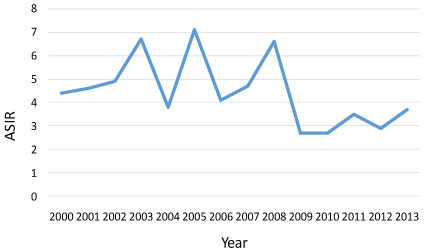

Overall, the age standardized rate of cervical cancer in Bahrain has decreased from 4.4 in 2000 to 3.7 in 2013 [13]. It has peaked to 7.1 in 2005, followed by fluctuations till it reached 3.7 in 2013. A study about cervical cancer prevention in Bahrain was done in 2009. It has shown that routine cervical screening was introduced in postnatal clinics of hospitals in the early 2000s, and that postnatal and antenatal clinics were made available in all heath centres at that period. This was also accompanied by increased collection of cytology smears from 2001 to 2007 [14]. This is in line with the overall decrease of ASIR from 2000 to 2013. Patients' attitudes towards screening also have an impact on the screening coverage of the country. A recent study conducted about knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding cervical cancer and screening among women visiting primary health care centres in Bahrain had shown that 194 out of 300 participants (65%) have heard about Pap Smears. This designates the advancement in the awareness and knowledge of the patients about screening [15]. Graph 1 shows the overall trend in the ASIR of cervical cancer in Bahrain from the year 2000 to 2013.

One of the limitations of this study is the complete case analysis which essentially revolves around dropping missing cases from the analysis leaving only complete cases.

Although cancer registry contains details of basic demographic information and information about the cancer, it lacks information about aetiology (specific strain of the virus), host determinants such as family history and comorbidities, treatment patterns, outcomes, recurrence and survival. Further, the information available on clinical management in the registry might not be as accurate as it should be or up to date. The notification form is usually filled and submitted as soon as the patient is diagnosed and therefore the treatment might have not been completed at that stage. With missing data representing a main challenge to epidemiological research and with over a third of cases in this study are of unknown grading, more efforts should be directed towards completing missing information in the registry. This is only achieved with the collaborative work of registrars or data technologists, clinicians, particularly oncologists, pathologists, diagnostic imaging specialists and other healthcare professionals.

In addition to the importance of raising the awareness about early detection of cervical cancer, it is equally important to educate the public (both men and women) about the main etiology of cervical cancer, ways of transmission and the importance of HPV vaccine.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study established the epidemiological profile of cervical cancer in Bahrain between 2005-2015, outlining the demographics of patients, types of cancer, pathological features and therapeutic modalities. The study findings revealed important implications to the formulation of new healthcare strategies and policies, particularly in regards to cervical cancer screening and introducing the HPV vaccine into the immunization schedule.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study had been ethically approved by the Ministry of Health and by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland-Medical University of Bahrain. Consent was waived as this study dealt with human data available from the Registry.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Authors' contributions

AM, MQ and ZA developed the research protocol, gathered data and had a major role in data analysis and interpretation. They contributed to writing the first draft of the manuscript. GJ supervised the whole research process and had a major role in analysing the data and writing the manuscript. NA helped in gathering the data and editing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

References

- Globocan (2018) Fact Sheets by Cancer.

- Al-Othman S, Haoudi A, Alhomoud S, et al. (2015) Tackling cancer control in the Gulf cooperation council countries. Lancet Oncol 16: e246-e257.

- HPV Information Centre (2017) Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report. Bahrain.

- Cancer Research UK (2015) Cervical cancer incidence statistics.

- G Hoste, K Vossaert, WAJ Poppe (2013) The clinical role of HPV testing in primary and secondary cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol Int 2013: 1-7.

- IACR (2018) Bahrain Cancer Registry.

- Berraho M, Bendahhou K, Obtel M, et al. (2012) Cervical cancer in Morocco: Epidemiological profile from two main oncological centers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13: 3153-3157.

- Benard VB, Watson M, Castle PE, et al. (2012) Cervical carcinoma rates among young females in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 120: 1117-1123.

- Marth C, Landoni F, Mahner S, et al. (2017) Cervical cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 28: 72-83.

- Adegoke O, Kulasingam S, Virnig B (2012) Cervical cancer trends in the United States: A 35-year population-based analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 21: 1031-1037.

- Bonanni P, Bechini A, Donato R, et al. (2015) Human papilloma virus vaccination: Impact and recommendations across the world. Ther Adv Vaccines 3: 3-12.

- Moosa K, Alsayyad AS, Quint W, et al. (2014) An epidemiological study assessing the prevalence of human papillomavirus types in women in the Kingdom of Bahrain. BMC Cancer 14: 905.

- Al Awadhi M, Abulfateh N, Abu-Hassan F, et al. (2016) cancer incidence and mortality in the kingdom of Bahrain statistics and trends. Bahrain Medical Bulletin 38: 30-34.

- Rajab K, Issa A, Jamsheer H (2009) Cervical cancer prevention in Bahrain-Review. Bahrain Medical Bulletin 31: 27-33.

- Jassim G, Obeid A, Al Nasheet HA (2018) Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding cervical cancer and screening among women visiting primary health care Centres in Bahrain. BMC Public Health 18: 128.

Corresponding Author

Ghufran Jassim, Senior Lecturer, Family Medicine Department, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland-Medical University of Bahrain, PO Box 15503 Adliya Bahrain, Bahrain.

Copyright

© 2019 Jassim G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.