Neonatal Sepsis and Associated Factors among Neonates Admitted to NICU in Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Sidama Regional State, South Ethiopia, 2020

Abstract

Background: Neonatal sepsis is a condition defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by signs and symptoms of infection in an infant 28 days of life or younger. In Ethiopia, regardless of the marked reduction in neonatal mortality neonatal sepsis still accounts for more than one-third (33%) of neonatal deaths in the country. Thus, identification of the magnitude and associated factors of neonatal sepsis has vital role in preventing and minimizing the related burden of neonatal illness and death.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to assess the magnitude of neonatal sepsis and its associated factors among neonates admitted to NICU, in Hawassa University comprehensive specialized Hospital, Sidama regional state, Ethiopia, 2020.

Materials and methods: Institution based cross-sectional study design was carried out among 287 neonates admitted to NICU at Hawassa University comprehensive specialized Hospital from April 25 to May 31/2020. Systematic random sampling technique was used to reach at study participants. Data was collected using pretested structured questionnaire and checked for completeness and consistency on a daily basis. Cleaned data was coded and entered in to Epi data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS software version 22.0 for analysis. Bivariate and Multivariable logistic regression analysis was done to identify variables having a significant association with neonatal sepsis. Variables with p-value < 0.05 at 95% CI was considered as having a statistically significant association with outcome variable.

Result: The study showed that the magnitude of neonatal sepsis was 56%. The finding revealed that mothers who delivered by Caesarean section [Adjusted Odds ratio [AOR = 2.13, 95% CI (1.090-4.163)], Neonates who had been resuscitated at birth [AOR = 4.5, 95% CI (2.083-9.707)] and Neonates who had NG tube inserted [AOR = 4.29, 95% CI (2.302-8.004)] were found to be significantly associated with neonatal sepsis.

Conclusion: The current study shows that neonatal sepsis among study population was high. Factors such as mode of delivery of the neonate, resuscitation during birth and NG tube insertion were contributed to occurrence neonatal sepsis.

Keywords

Neonatal sepsis, Neonates, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Magnitude, Hawassa, Ethiopia

List of Abbreviation

ANC: Antenatal Care; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; APGAR: Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration; CI: Confidence Interval; COR: Crude Odds Ratio; C/S: Cesarean section; EDHS: Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey; HUCSH: Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital; KMC: Kangaroo Mother Care; MSAF: Meconium stained amniotic fluid; MDG: Millennium Development Goal; NGT: Naso gastric Tube insertion; NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; SPSS: Statistical software for social science; SSA: Sab-Saharan Africa; UNICEF: United Nation Children Fund; WHO: World Health Organization

Background

Neonatal sepsis is a condition defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by signs and symptoms of infection in an infant 28 days of life or younger [1]. It is a serious blood bacterial infection in neonate which is manifested by systemic signs and symptoms of infection [2,3]. The manifestations of neonatal sepsis are nonspecific and vary among neonates [4]. World health organization (WHO) has recognized seven clinical indicators such as difficulty feeding, convulsions, the movement only while stimulated /lethargy, respiratory rate of > 60 breaths in a minute, chest in drawing, temperature of > 37.5 °C or < 35.5 °C and respiratory distress [5]. Another study has additionally incorporated cyanosis and grunting [6].

Globally, neonatal sepsis is one of the most significant causes of morbidity and mortality among neonates during the neonatal period (0-28 days) [7]. Out of 5.9 million child deaths in 2015, almost 1 million occur in the first day of life, close to 2 million occurs in the first week of life [8]. Post MDG report indicated that despite the significant progress that has been made during the MDG era, sepsis is still one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in neonates because of their weak and immature immune systems related to their age [7]. Despite improvements occur in the diagnosis and management of neonatal sepsis in recent years, NS become a leading cause of admission and death in neonatal units especially in developing countries [9].

In 2018 approximately four million global neonatal deaths occur per year, 7000 newborn deaths every day, accounting for 47% of all child deaths under the age of 5-years, and 2.5 million children died in the first month of life [10,11]. Of which about 98 % occurs in developing countries especially in sub-Saharan Africa [12]. The risk of neonatal death becomes 6 times higher in developing countries compared to that of developed countries [13]. According to the 2014 UNICEF report, neonatal deaths accounted for 52% of all under-five child mortality in South Asia, 53% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 34% in sub-Saharan Africa [14].

In spite of Ethiopia's remarkable success in achieving the millennium development goal (MDG 4) three years before, the reduction in neonatal mortality was comparatively low [15] and at the end of the MDG era the international community was in agreement on a new framework; the sustainable development goals (SDGs) to reduce newborn and under-five mortalities as low as 12/1000 and 25/1000 respectively by 2030. This could be achieved through better prevention and management of preterm births and severe infections [16].According to the2016 EDHS report, the neonatal mortality rate (NMR) was 29/1000 live births, which shows a small significant reduction from the 2011 EDHS report of 37/1000 live births [17,18].

Neonatal sepsis is the major cause of newborn death in Ethiopia, which constitutes more than one-third of neonatal deaths [19,20]. Although the causes of neonatal mortality are not well documented in Ethiopia, reports from various literature mentioned neonatal sepsis, asphyxia, birth injury, tetanus, preterm birth complications, intrapartum-related complications, and congenital malformations were cited as major reasons for neonatal mortality [21]. In order to avert significant mortality among neonates, the Every Newborn Action Plan, launched in June 2014, provides a stimulus to accelerate progress by implementing effective cause-specific interventions that can rapidly reduce neonatal mortality [22,23]. According to a 2015 UN report, neonatal death is reduced by 48% from the 1990 estimate to 28 per 1000 live births in 2013 while, the under-5 mortality rate has declined to 67% [24].

Even though several studies were carried out to assess the magnitude and associated factors of neonatal sepsis in Ethiopia [25-36], the findings were inconsistent and varied. As documented in different works of literature, neonatal sepsis is caused by factors related to both maternal and neonatal conditions birth weight, prematurity, and birth asphyxia [25,27,31,33,35] use of endo tracheal intubation, resuscitation at birth, and surgery were significant predictors of [31,37,38] neonatal sepsis. Maternal factors such as prolonged rupture of membrane, urinary tract infection, intrapartum fever, duration of labor, mode of delivery, and place delivery [15,23,25,32] were associated with neonatal sepsis.

Studies also revealed that Neonates born from women with meconium-stained amniotic fluid, age less than 20 years old mothers who received antibiotics during labor and delivery, more than three times digital per vaginal examination and never attend antenatal care (ANC) are at higher risk for neonatal sepsis [27,31,39-41]. Even though the improvements were done in the diagnosis and management of neonatal sepsis in recent years in Ethiopia, the admission of neonates to the NICU with infection, most typically sepsis has been increased and the mortality rates were stagnant. Despite this fact, there is no enough study conducted nationwide generally and in the study area particularly. Therefore; the main objective of this study is to assess the magnitude of neonatal sepsis and associated factor at Hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia, 2020.

Methods and Materials

Study design

An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted.

Study Area and Period

This study was conducted at Hawassa compressive specialized Hospital. Hawassa city is found 275 km far from Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. The former hospital was established in November 2005 for the purpose of health professionals training and health care service delivery. It has about 400 beds and expected to serve more than 18 million people in the Southern regions of Ethiopia. The Neonatology unit of the hospital has 9 pediatricians and 25 Nurses. It is well equipped and gives a full range of Neonatal service. Total Neonate admissions in Hawassa Compressive Specialized hospital was 1700 per year at 2011E.C. The study was conducted from March 1, 2020, to April 25, 2020, in Hawassa city, Hawassa university comprehensive specialized hospital, NICU.

Population

Source population

All neonates who were delivered at and admitted to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

Study population

Sampled neonates who were admitted to NICU in Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

All neonates who were admitted to Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital at neonatal intensive care unit were included in this study

Exclusion criteria

All neonates whose mother died of birth and without family who cannot disclose their information were excluded.

Sample size determination

The sample size is calculated using the single population proportion formula by taking the magnitudeof neonatal sepsis 21 % from a study conducted at Shashemenne town [42].

Where, D = margin of error (5% = 0.05)

P = best estimate of population proportion (21.0% = 0.21)

Q = 1-P = 0.79

Z = confidence level (95% = 1.96)

Sample size will be:

By adding a 10% non-response rate, the final sample size became 287.

We also calculate the sample size using Epi info software for the second objective by taking variables like Birth asphyxia (AOR=3.54), Age of neonate (AOR=3.01), and Premature Rupture of Membrane (PROM) (AOR=7.43) which showed statistically significant association with Neonatal sepsis and yields a sample size of 138, 148 and 188 respectively. Based on this the sample size resulted from the single population proportion formula (i.e. Proportion of neonatal sepsis) which is 287 was taken as a sample size for this study.

Sampling technique and procedure

A systematic random sampling procedure was used to select study participants from listed admitted newborns at NICU. The total number of neonates (N) was estimated by considering the client flow in the last year by reviewing the registration of neonates that yielded a total of 1700 neonates. Then the number of sampling intervals was determined by dividing the number of neonates (N = 1700) by estimated sample size (n = 287) and hence the sampling interval (k) was 6. The first sampling unit was selected by the lottery method and every 6th unit was taken until it reached the sample size.

Variables

Dependent variable

Neonatal sepsis (Yes/No).

Independent variables

Socio-demographic characteristics: Age of neonate, sex of neonate, maternal age, residence, educational status of the mother and monthly income.

Maternal factors: Parity, history of UTI, foul-smelling amniotic fluid, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, ANC, duration of rupture of membrane, the person assisting delivery, place of delivery, frequency of PV examination, maternal fever.

Neonatal factors: Prematurity, low birth, APGAR score status, breastfeeding ability, birth defect/anomaly, surgical procedure, resuscitation, intubation, umbilical catheterization.

Operational definition

Neonate

Newborn baby less than 28 days of life since delivery.

Neonatal sepsis

Neonates with the presence of at least one clinical sign plus at least two laboratory results which are suggestive for neonatal sepsis or neonates who are diagnosed as sepsis by attending physician and fulfill sepsis criteria within 0-28 days of life. According to this study, the magnitude of neonatal sepsis was determined using WHO main clinical signs (criteria) for diagnosing neonatal sepsis; and a neonate having two or more signs from (Convulsion, Respiratory rate > 60breaths/min, Temperature > 37.5C or < 35.5C, Not able to feed, Severe chest in drawing, Reduced movement and Grunting) was considered to have neonatal sepsis. Accordingly the main clinical signs, the least expected score of the neonate to have no neonatal sepsis is 13 (coding 'Yes' as 1 and 'No' as 2) and the least expected score of the neonate to have neonatal sepsis is 12. Therefore, the neonate with a score of ≥ 13 was considered as having no neonatal sepsis and with score ≤ 12 (score ranging from 7 to 12 (including)) were considered as having neonatal sepsis.

Data collection instrument and procedure

The data were collected using pre-tested, structured, and interviewer-administered questionnaires which contain three main parts; socio-demographic characteristics of the child and caregiver, maternal-health related and Neonatal-health related factors through face to face interview of the caregivers. The interview was conducted in a private room to create an atmosphere of empathy and confidence within a secure environment. Chart review was also done to identify the neonatal reasons for admission and lab investigation was taken from the client chart. Data were collected by four midwives (4) who are fluent in 'local language' and currently working in Hawassa University's comprehensive specialized hospital. The data collection process was supervised by two (2) Bachelor of sciences (BSC) Nurses. Finally, filled questionnaires were checked for completeness and consistency of the data by the principal investigator on daily basis.

Data quality control

The quality of data was ensured through training of data Collectors and pretesting of the questionnaire. The principal investigator along with data collectors made frequent checks on the data collection process to ensure the completeness and consistency of the gathered data and daily based corrections were made accordingly. Most of the questions were adapted from previously conducted studies with some changes based on the local context and data was collected by a health care provider who had a better experience in data collection. The questionnaire was translated into Amharic by an expert translator and then back to English to ensure consistency of questions (meaning). The questionnaire was pre-tested on 5% (15 neonates with caregivers) living in Shashemenie town which is out of the study area. In addition to this, the instrument was tested for reliability and validity, and accordingly; the cronbach's alpha coefficient was found to be very good. Then, necessary corrections were made to the tool prior to actual data collection.

Data processing and analysis

After checking for completeness, the data were coded and entered into Epidata version 3.1 and then exported to SPSS version 23.0 for analysis. The results of the analysis were mainly presented using frequency, tables, and graphs. A bi-variable logistic regression was carried out to determine candidate variables for the multivariable logistic regression model. Those variables which revealed statistically significant value at a p-value of ≤ 0.25 in the bivariable analysis were selected for multivariable logistic regression. For model fit, Hosmer and Lemeshow test was carried out and found to be (0.738) which indicated the final model was well fitted and The multicollinearity effect among candidate variables was carried out (checked) using variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance test between independent variables and found to be VIF < 5 (1.03-4.40) and tolerance test > 0.2.Variables with a p-value of ≤ 0.05 with 95% CI for AOR in multivariable logistic regression were used to determine the statistically significant association between independent and dependent variables.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Pharma College of health science. Official letters were taken from Hawassa University's comprehensive specialized hospital. The study participants were informed about the purpose of the study and informed verbal consent was also obtained.

Results

Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of mothers

A total of 287 neonates who were admitted in NICU with their mothers were included in this study with an overall response rate of 100%. According to this study, the mean age of mothers was 26.9 (SD±4.6) years. Most of the mothers of the neonates were from urban areas (59.9%) and most of them 256(88.2%) were married (Table 1).

Maternal related factors for neonatal sepsis

Of the total mothers of the neonates, more than half 164 (57.1%) were primiparous and 234 (81.5%) had antenatal care visits for the index neonate, of which 105 (36.6%) and 79 (27.5%) of them had three and four visits respectively. Concerning the place of delivery, all mothers gave birth in health facilities, 191 (66.6%) and 96 (33.4%) delivered in hospitals and health centers respectively. and nearly two-third of 174 (60.6%) of mothers gave birth with spontaneous vaginal delivery followed by 74 (25.8) with cesarean section. During labor, 251 (87.5%) mothers had ≤ 4 digital vaginal examinations, and 200 (69.7%) of mothers brown (green) discoloration of amniotic fluid, and 80 (27.9) had foul-smelling amniotic fluid. In addition, 81 (28.2%) of mothers had a history of pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Neonatal Related factors for neonatal sepsis

According to this study, the mean age of neonates was 3.2(SD ± 2.2) days and more than half 157 (54.7%) of them were females. Concerning gestational age, about three-fifth (58.9%) and two-fifth (39%) of neonates were in the gestational age of 38-42 and < 37 completed weeks respectively. About 286 (99.7%) and 250 (87.1%) of neonates had an Apgar score of ≤7 at first and fifth minutes respectively. about half of neonates 147 (51.2%) had low birth weight (< 2500grams). About two-third of 194 (67.6%) and three-fourth 215 (74.9%) of neonates did not cry and had been resuscitated at birth respectively. In addition, 234 (81.5%) of neonates were on oxygen, and 128 (44.6%), 90 (31.4%), and 16 (5.6%) of them were administered the oxygen through a nasal cannula, mask, and intranasal catheter respectively. Moreover, about half of neonates 145 (50.5%) had an NG tube inserted.

Magnitude of main clinical signs of neonatal sepsis

Accordingly, the main clinical signs to diagnose neonatal sepsis as recommended by WHO, out of 287 neonates admitted to NICU, more than two-third 197 (68.6%) had respiratory rate > 60breaths/min; among them, 141 (49.1%) had developed neonatal sepsis and about 109 (38%) had temperature instability (> 37.5oC or < 35.5oC); out of this, 92 (32.1%) had developed neonatal sepsis. About 51(17.8%) of neonates had a severe chest in drawing and 48 (16.7%) of them developed neonatal sepsis. In addition, 117 (40.8%) of neonates had grunting; among them, 105 (36.6%) were suffering from neonatal sepsis; and 45 (15%) of neonates had difficulty feeding; out of the 42 (14.6%) developed neonatal sepsis.

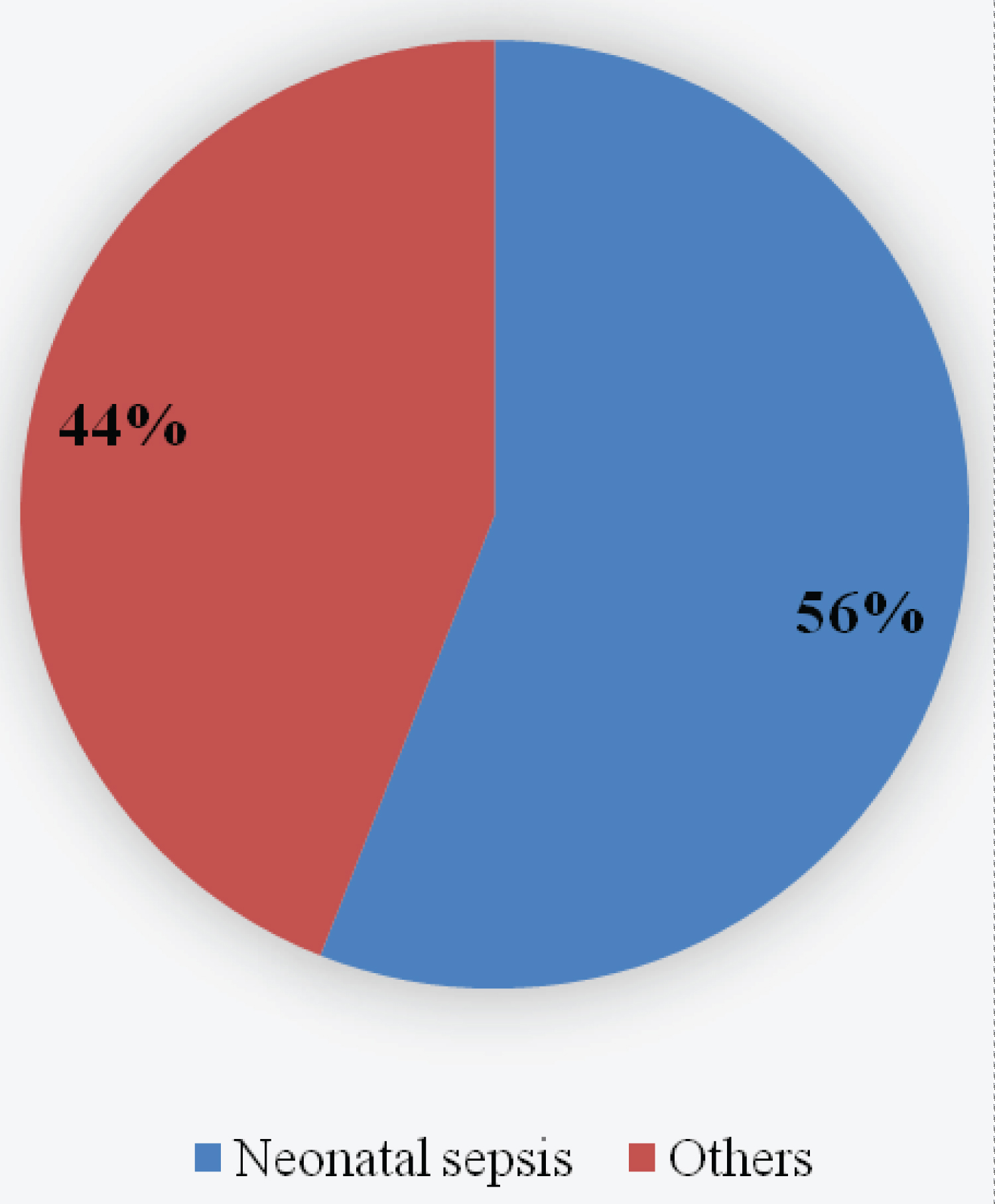

Magnitude of neonatal sepsis

Among 287 neonates admitted to NICU, 162 (56%) had neonatal sepsis whereas 125 (44%) had been admitted for other diseases (Figure 1).

Factors associated with neonatal sepsis

To assess the association of different independent variables with the outcome variable (neonatal sepsis), Bivariable logistic regression analysis was carried out and for a crude association, all variables with a p-value less than 0.25 (P-Value < 0.25) were become a candidate for multivariable logistic regression. Among the candidate variables, mode of delivery, ANC follow up, maternal fever, brown (green) discoloration of amniotic fluid, birth weight, APGAR score at 5th minute, with an immediate cry of the neonate at birth, resuscitation at birth, and neonate with NG tube inserted were significantly associated with neonatal sepsis in Bivariable logistic regression at P-value < 0.05.

From a multivariable analysis, mode of delivery, resuscitation at birth, and neonate with NG tube inserted were found to be significantly associated with neonatal sepsis at P-value < 0.05.

This study showed that mothers who delivered by Caesarean section were about two folds more likely to have their neonates higher chance of developing neonatal sepsis than those delivered by spontaneous vaginal delivery [AOR = 2.13, 95% CI (1.090-4.163)]. Similarly, the analysis revealed that neonates who had been resuscitated at birth were 4.5 times more likely to develop sepsis than those without resuscitation at birth [AOR = 4.5, 95% CI (2.083-9.707)].

Our study also found that neonates who were NG tube inserted were >4 times thehigh risk for developing neonatal sepsis compared to those without NG tube [AOR = 4.29, 95% CI (2.302-8.004)].

Discussion

The magnitude of neonatal sepsis in the present study was found to be 56%. This finding is relatively congruent to the study finding in southern Ethiopia (57.5%), Gondar (59%) [33], Jimma (52.6%) [28] and Iran (51.8%) [42] and it is lower than the study finding in Arbaminch (78.3%) [35], Shashemene (77.9%) [34], Sudan (65.8%) [40] and Ghana (78.7%). But the present study finding was relatively higher than the study finding in Gondar (11.1%) [43], Wolaita Sodo (33.85%) [44], Oromia, Arsi (34%) [27], Systemic review and meta-analysis in Ethiopia (45%) [45], Black Lion (44.7%) [46], Bahirdar (49.98%) [30], Uganda (11%) [39], Tanzania (31.4%, 49.8%) [40,47], systemic review and meta-analysis in developing country (29.2%) [48], Bangladesh (12%) [49], India (19%) [50], Jordan (12%) [51], Taiwan (15.2%) [52] and Srilanka (4.6%) [53]. The reason for this difference might be due to difference in Socio-demographic characteristic, sample size, study design, accessibility of health facility, skilled manpower/personnel, advanced equipment/health system, and differences in the way neonatal sepsis has been asserted as well as the techniques used to operationally define neonatal sepsis could be the attributes for the difference.

The current study revealed that 48.4% of neonates born to mothers who had ANC Visit developed neonatal sepsis. This finding is higher than the studies conducted in Northwest parts of Ethiopia in which cases 30.1% and 24.7% of neonates developed sepsis [31,54]. Meconium stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) is another maternal-related factor that increases the likelihood of developing neonatal sepsis. Neonates born to women with MSAF are more liable to aspirate it and fill smaller airways and alveoli in the lung; this in turn increases the multiplication of pathogens that cause sepsis, specifically, late onset of neonatal sepsis. The present study indicated that about 44% of neonates born to mothers who had MSAF developed sepsis. This finding is relatively higher than the study finding from the Northwest part of Ethiopia (18.6%) and Shashemene town, Oromia region (4.1%) [31,34].

Gestational age is one of the neonatal related factors that contribute to developing neonatal sepsis. In the present study, 28.2% of neonates with gestational age < 37 and ≥ 37 completed weeks had developed sepsis. This finding is relatively lower than the study finding in Arbaminch general hospital, Southern Ethiopia, and Shashemene, Oromia region [34,35]. But is relatively higher than the studies conducted in northwest parts of Ethiopia [54], Mekelle (North Ethiopia), [55] and Ghana [56]. Though neonates have immature immunity, especially, preterm (< 37 weeks gestational age), the difference might be due to intrauterine factors, health facility-related factors, and different procedures during and after delivery.

In the present study, mode of delivery (Cesarean section), resuscitation at birth, and neonate with NG tube inserted were maternal and neonatal variables significantly associated with neonatal sepsis. Cesarean section (C/S) delivery was statistically associated with the risk of developing neonatal sepsis in which case newborns delivered through cesarean section were about >2 times more likely to have a higher chance of developing neonatal sepsis than those delivered by spontaneous vaginal delivery [AOR = 2.13, 95% CI (1.090-4.163)]. This finding is consistent with the study finding in Ghana [38] and Iran [57] Newborns delivered through CS have a limited chance to be exposed to vaginal and fecal bacteria; but developing neonatal sepsis, in this case, might be related to late initiation of breastfeeding, poor aseptic technique during operation, lack of fumigation of the operation room, prolonged second stage of labor and prolonged hospital stay. Moreover, Cesarean sections, especially before 39 weeks of pregnancy, can be associated with several adverse neonatal events, such as respiratory complications and hypoglycemia due to prematurity. This leads to higher NICU admissions and higher chances of developing newborn sepsis.

Our finding investigated that resuscitation at birth was significantly associated with neonatal sepsis. Neonates who had been resuscitated at birth were nearly five times more likely to develop sepsis than those without resuscitation at birth [AOR = 4.5, 95% CI (2.083-9.707)]. This finding is congruent with findings from other studies: Northwest parts of Ethiopia (2019 and 2020) [31,54], Jimma [28], Ghana [58], and Tanzania [40,47]. This might be related to contaminated and forceful procedures during resuscitation that might cause laceration and easily breakage of the mucous membrane of the neonate that creates a conducive route for entering pathogens from unsterile equipment. Besides this, the lumen of the peripheral airway of the newborn is narrow and respiratory secretions are plentiful which could predispose the newborn to atelectasis. For the collapse of the lungs, performing vigorous procedures is may cause bruises to the delicate and fragile mucous membrane of the neonate and further serve as an entry point for microbial agents.

The current study also revealed that nasogastric tube insertion (NGT) was a neonatal related factor that was significantly associated with neonatal sepsis. Neonates who were NG tube inserted were > 4 times the high risk for developing sepsis compared to those without NG tube [AOR = 4.29, 95% CI (2.302-8.004)]. This finding was relatively in line with study findings from Northwest Ethiopia [31], Turkey [42], and Taiwan [52]. This might be due to the fact that not performing procedures aseptically and carefully that that might break the mucous membrane of newborns and create easy accessibility of pathogenic organisms.

Conclusion & Recommendation

Generally, the current study shows that neonatal sepsis was prevalent among more than half (56%) of the neonates admitted in the NICU which is still very high. Furthermore, the mode of delivery of the neonate, resuscitation during birth, and NG tube insertion were the major predictors of neonatal sepsis. According to the findings from this study, the following recommendation has been suggested to different stakeholders.

For health care workers

Professionals who are working in the labor ward should follow laboring mothers strictly and should adhere to aseptic precautions while performing invasive procedures.

For mothers

Women who didn't have complete ANC service should get all their antenatal care schedules according to the Ethiopian Ministry of Health(EMH) and take prompt action in seeking medical help during an obstetric emergency including rupture of membrane before labor.

For the ministry of health and health service organization

The government should increase the political priority given to sepsis by improving awareness of the growing medical and economic burden of neonatal sepsis. Primary care organization should increase their support towards maternal education and incorporate routine neonatal sepsis screening into the care of neonates and mothers.

Strength and Limitation of the Study

Strength of the study

Having a response rate of 100% and Utilization of a valid and standardized instrument could be the strength of the current study.

Limitation of the study

This study cannot ascertain cause and effect relationship between outcome variable and predictors' variables. since it is a cross-sectional type and since the study was done on admitted neonates, thus results might lack generalizability to the entire population.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Pharma College of health science. Official letters were taken from Hawassa university's comprehensive specialized hospital. The study participants were informed about the purpose of the study and informed verbal consent was also obtained.

Consent for publication

The study does not include images of or videos relating to the individual. But concerning other collected and used data in this study; while obtaining consent from each participant, information related to publishing the study finding was addressed and participants were agreed on that.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author under the reasonable request.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding

Not applicable for the publication of this manuscript.

Authors' Contributions

BZ: - The principal investigator has conceived of the study, carried out the overall design and execution of the study, design of questionnaires, performed the data collection, performed the statistical analysis, and served as the lead author of the manuscript.

TT:- Equally participated in the conceptualization of the study, design, analyses, and interpretation of results as well as drafting and review of the manuscript.

FS: - Equally participated in the conceptualization of the study, design, analyses, and interpretation of results as well as drafting and review of the manuscript.

FA: - Equally participated in the conceptualization of the study, design, analyses, and interpretation of results as well as drafting and review of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost we would like to thank Hawassa University comprehensive specialized Hospital for funding this research project. Secondly, we would like to express our profound gratitude to Hawassa university's comprehensive specialized hospital NICU staff for their valuable supports while collecting the data. Our thanks also go to all data collectors for carrying out their responsibilities effectively during the data collection and all study participants for their willingness to participate in the study.

References

- Edwards MS and Baker CJ (2004) Sepsis in the newborn. In: Gershon AA, Hotez PJ, Katz SL, ed. Krugman’s Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; Infect Dis Child 545.

- Warf BC, Alkire BC, Bhai S, et al. (2011) Costs and benefits of neurosurgical intervention for infant hydrocephalus in sub-Saharan Africa. J Neurosurg Pediatr 18: 509-521.

- Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A (2005) International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatric critical care medicine: J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc 6: 2-8.

- United Nations (2015) The Millennium Development Goals Report.

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development.

- Ranjeva SL, Warf BC, Schiff SJ (2018) Economic burden of neonatal sepsis in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Health 3: e000347.

- Fleischmann-Struzek C, Goldfarb DM, Schlattmann P, et al. (2018) The global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: a systematic review. Lancet Respir Med 6: 223-230.

- IGME (2015) Levels and Trends in Child Mortality.

- Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J (2005) Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet 365: 891-900.

- WHO (2018) Neonatal mortality. Global Health Observatory.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF (2017) 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey Key Findings. Addis Ababa.

- Seale AC, Blencowe H, Manu AA, et al. (2014) Estimates of possible severe bacterial infection in neonates in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America for 2012: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 14: 731-741.

- Edmond K and Zaidi A (2010) New approaches to preventing, diagnosing, and treating neonatal sepsis. PLoS Med 7: e1000213.

- UNICEF (2014) Committing to Child Survival: A Promise Renewed.

- Hisham Medhat, Abdelmoneim Khashana, Mohamed El kalioby (2017) Incidence of Neonatal Infection in South Sinai, Egypt. Int J Infect 4: e36615.

- WHO (2016) World health statistics: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data 1-136.

- Central SA and Ababa A (2011) Ethiopia: Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey Preliminary Report, Ethiopia, ICF International Calverton, Maryland, USA 1-29.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (Ethiopia) and ICF (2016) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF 2016.

- Berhanu D and Avan BI (2014) Community- Based Newborn Care Baseline Survey Report Ethiopia, October 2014.

- UNICEF (2014) Ethiopia - health maternal health brief.

- Klein JO and Remington JS (2010) Current concepts of infection of the fetus and newborn infant. In: Infect Dis Fetus Newborn: 1-24.

- Assefa Y, Van Damme W, Williams OD, et al. (2017) Successes and challenges of the millennium development goals in Ethiopia: Lessons for sustainable development goals. BMJ Glob Heal 7: 1-7.

- Seale AC, Blencowe H, Zaidi A, et al. (2013) Neonatal severe bacterial infection impairment estimates in South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America for 2010. Pediatr Res 74: 73-85.

- Ribbon W. No Title. 2017;1-7.

- Erkihun Ketema, Mesfin Mamo, Direslegn Miskir, et al. (2019) Determinants of neonatal sepsis among neonates admitted in a neonatal intensive care unit at Jinka General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia 11: 18-24.

- Alemu M, Ayana M, Abiy H, et al. (2019) Determinants of neonatal sepsis among neonates in the northwest part of Ethiopia: a case-control study. Ital J Pediatr 45: 150.

- Sorsa A (2019) Epidemiology of Neonatal Sepsis and Associated Factors Implicated: Observational Study at Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Arsi University Teaching and Referral Hospital, South East Ethiopia 29: 333-342.

- Bayana E, Endale K, Olani A, et al. (2020) Neonatal Sepsis among Neonates at Public Hospitals in Jimma, Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr 8: 12011-21.

- Mekonnen Y, Tensou B, Telake D, et al. (2013) Neonatal mortality in Ethiopia: trends and determinants. Int J Nurs Midwifery 13: 2-4.

- Amare Belachew and Tilahun Tewabe (2020) Neonatal sepsis and its association with birth weight and gestational age among admitted neonates in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 20.

- Akalu TY, Gebremichael B, Desta KW, et al. (2020) Predictors of neonatal sepsis in public referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: A case-control study 15: e0234472.

- AbdurahmenJ, AddissieA and Molla M (2012) Preferences of Place of Delivery and Birth Attendants among Women of Shashemene Town, Oromia Regional State 2: 1-19.

- Kassie DG, Tewolde AWS and BogaleWA (2020) Premature Rupture of Membrane and Birth Asphyxia Increased Risk of Neonatal Sepsis Among Neonates Admitted in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at the University of Gondar Specialized Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. Pediatr Infect Dis 5: 1.

- Aytenew Getabelew et al. (2018) Magnitude of Neonatal Sepsis and Associated Factors among Neonates in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Selected Governmental Hospitals in Shashemene Town, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia, 2017. Int J Pediatr 2018:7801272.

- Mustefa A, Abera A, Aseffa A (2020) Magnitude of neonatal sepsis and associated factors amongst neonates admitted in Arbaminch general hospital, Arbaminch, southern Ethiopia, 2019. J Pediatr Neonatal Care 10: 1-7.

- Magnitude of Neonatal Sepsis in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

- Bahl R, Seale AC, Blencowe H, et al. (2012) Estimates of possible severe bacterial infection in neonates in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America for 2012 : a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 14: 731-741.

- Agani Afay, Solomon Mohammed Salia, Peter Adatara, et al. (2019) Risk Factors Associated with Neonatal Sepsis: A Case Study at a Specialist Hospital in Ghana, 2018. Sci World J 8.

- John B, David M, Mathias L, et al. (2015) Risk factors and practices contributing to newborn sepsis in a rural district of Eastern Uganda,August 2013 : a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 1.

- Jabiri A, L. Wella H, Semiono A, et al. (2016) Magnitude and factors associated with neonatal sepsis among neonates in Temeke and Mwananyamala Hospitals in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res 18: 1-7.

- Ahmed MA and Magzoub OS (2015) Risk factors for neonatal sepsis in the pediatric ward at Khartoum North Teaching Hospital, Sudan. Res J Med Clin Sci 4: 37-43.

- Getabelew A, Aman M, Fantaye E, et al. (2018) Magnitudeof Neonatal Sepsis and Associated Factors among Neonates in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Selected Governmental Hospitals in Shashemene Town, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia, 2017. 2018.

- Ertugrul S, Aktar F, Yolbas I, et al. (2016) Risk Factors for HealthCare-Associated Bloodstream Infections in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Iran J Pediatric 26: e5213.

- Yismaw AE, Biweta MA and Araya BM (2019) The proportion of neonatal sepsis and determinant factors among neonates admitted to the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital neonatal Intensive care unit Northwest Ethiopia 2017. BMC Res Notes 12: 3-7.

- Mersha A, Worku T, Shibiru S, et al. (2019) Neonatal sepsis and associated factors among newborns in hospitals of Wolaita Sodo Town, Southern Ethiopia. Res Rep Neonatol 2019: 1-8.

- Moges Agazhe Assemie, Muluneh Alene, Lieltwork Yismaw, et al. (2020) Magnitudeof Neonatal Sepsis in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Pediatr 9.

- Demissie S (2008) Neonatal sepsis: Bacterial etiologic agents and their antibiotic susceptibility pattern in Tikur Anbessa University Hospital, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia. 2008.

- Kiwone, Nikolaus S. Chotta, Daniel Byamungu, et al. (2020) Magnitude and factors associated with neonatal sepsis among hospitalized newborns at Ruvuma, southern Tanzania. South Sudan Med J 13: 86-9.

- Desalegne Amare, Masresha Mela, Getenet Dessie (2019) Unfinished agenda of the neonates in developing countries: the magnitude of neonatal sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 5: e02519.

- Grace J Chan, Abdullah H Baqui, Jayanta K Modak, et.al. (2013) Early-onset neonatal sepsis in Dhaka, Bangladesh: risk associated with maternal bacterial colonization and chorioamnionitis. Trop Med Int Health 18: 1057-1064.

- Mamta Jajoo, Kapil Kapoor, LK Garg, et al. (2015) To Study the Incidence and Risk Factors of Early Onset Neonatal Sepsis in an Out born Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of India. J Clin Neonatol 4: 91-95.

- Dasoky HA Al, Awaysheh FN Al, Kaplan NM (2009) risk factors for neonatal sepsis in tertiary hospitals in Jordan 16: 16-19.

- Kung YH, Hsieh YF, Weng YH, et al. (2016) Risk factors of late-onset neonatal sepsis in Taiwan: A matched case-control study. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 49: 430-435.

- K S Y Perera, M Weerasekera, U D T M Weerasinghe (2018) Risk factors for early neonatal sepsis in the term baby. Sri Lanka J Child Health 47: 44-9.

- Alemu M, Ayana M, Abiy H, et al. (2019) Determinants of neonatal sepsis among neonates in the Northwest part of Ethiopia: a case-control study. Ital J Pediatr 45: 150.

- Gebremedhin D, Berhe H and Gebrekirstos K (2016) Risk Factors for Neonatal Sepsis in Public Hospitals of Mekelle City,North Ethiopia,2015: Unmatched Case-Control Study. PLoSONE 11: e0154798.

- Shahla A, Mohammad T, Amin S (2012) Trends in Incidence of Neonatal Sepsis and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Causative Agents in Two Neonatal Intensive Care Units in Tehran, I.R Iran. J Clin Neonatol 1.

- Siakwa M, Kpikpitse, Mupepi D, et al. (2014) Neonatal Sepsis In Rural Ghana: A Case-Control Study of Risk Factors in a Birth Cohort. Int J Res Med Health Sci 4.

Corresponding Author

Tigistu Toru, School of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Science, Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia

Copyright

© 2022 Toru T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.