Maxillofacial Bone Fracture Profiling amongst Adults and Elderly Population in Najran City, Southern Region of Saudi Arabia: A 20-Year Single Institutional Experience

Abstract

Introduction

Studies have shown that the pattern, incidence, and etiology of maxillofacial injuries differ between cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Maxillofacial injuries have not been extensively studied in southern Saudi Arabia, hence the justification for the present study.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective single tertiary hospital study of maxillofacial fractures in adults and elderly population from 1999-2019. Data collected include demographics such as age and gender, etiology, pattern and treatment of maxillofacial fractures. Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for windows Version 25 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Result

A total of 1007 patients suffered maxillofacial fractures during the study period. There were 973 males and 34 females with a M:F ratio of 29:1. Their ages ranged from 20-90-years with mean ± SD (30.4 ± 10.1) years. The age group from 20-30 years constituted the highest age group with maxillofacial fractures. Motor vehicular accident (MVA) accounted for the majority of the etiology in both genders, (86.3% males and 1.8% females). The most fractured bone was the mandible (47.4%). Within the mandible, the body was the most fractured site with 103 (10.2%) cases followed by angle 100 (9.9%), symphysis 87 (8.6%) and condyle 79 (7.8%) in decreasing order of frequency. Within the maxilla, Le Fort I fractures were the commonest fractures, comprising of 70 (7.0%) cases. Zygomatic body fracture was the most common, making up 228 (22.6%) of all fractures involving the zygomatic complex. Isolated orbital floor fracture was the most commonly observed among orbital fractures with 38 (3.8%) cases. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) was the commonest treatment modality and was used in 814 (80.8%) of the patients.

Conclusion

The results of the study revealed an overwhelming predilection of male gender over female and predominantly affected the age group between 20-30 years. MVA was the main etiologic factor and ORIF was the principal treatment modality. The data has brought out information for appropriate health education programs and application of firmer traffic rules to reduce accidents.

Keywords

Adults, Elderly, Maxillofacial, Trauma

Introduction

The epidemiology, patterns and management of the maxillofacial trauma in Southern Saudi Arabia have not been extensively studied and only two studies have so far been identified [1,2]. Although studies have reported the pattern and incidence of maxillofacial injuries in other regions in the Kingdom [3,4] to the best of our knowledge, none has been reported in Najran, a major city in the Southern Province of the Kingdom. The dearth of such information will make establishment of effective measures to prevent and manage such injuries difficult and lopsided [5]. Studies have shown that the epidemiology of maxillofacial fractures varies in etiology, form and severity depending on the population studied [3,6].

Road traffic accident (RTA), especially motor vehicular accidents (MVA), has been constantly stated as the leading etiology of maxillofacial fractures especially in the developing world including Saudi Arabia [2,3,7] although assault has been reported as the leading cause in the industrialized countries [8,9]. Apart from RTA and assaults, other common etiologies of maxillofacial fractures include sports, occupational accidents, domestic accidents, falls, and animal injuries [10,11].

The main aim of this present study was to analyze the maxillofacial fractures amongst the adult and elderly population, seen and treated at King Khalid Hospital, Najran, which is the only major tertiary referral hospital in Najran Region of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study of maxillofacial fractures seen and managed amongst adults and elderly in a major referral hospital in the Southern province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia over a 20-year period from 2000-2019. Data collected include demographics such as age and gender of patients, nationality, etiology and pattern of maxillofacial fracture as well as treatment modalities. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of King Khalid Hospital, Najran, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia with IRB number H-11-N-081. Inclusion criteria are cases of maxillofacial fractures in victims, aged 20-years and above, with complete medical records. Exclusion criteria are cases of maxillofacial bone fractures secondary to firearms injuries, victims under 20-years of age and cases with incomplete records.

Data was stored and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for windows Version 25 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Results were presented as simple frequencies and descriptive statistics. Pearson Chi-square was used to compare variables. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Result

A total of 1007 patients suffered maxillofacial fractures during the study period. There are 973 (96.6%) males and 34 (3.4%) females with a M:F ratio of 29:1. The victims included 763 (75.8%) Saudis and 244 (24.2%) non-Saudis. Their ages ranged from 20-90 years with mean ± SD (30.4 ± 10.1) years. The age group 20-40 years (88.3%) constituted the majority of the victims with maxillofacial fractures (Table 1).

Motor vehicular accident (MVA) accounted for the majority of the etiology in both genders (86.3% males and 1.8% females). This was trailed considerably behind by fall (3.3% male and 1.3% females). None from the female gender had maxillofacial fractures from sports, animal and occupational reasons (Table 1). There was significant difference when etiology was compared with age groups, as the age group of victims increases, MVA as cause of injury reduced significantly (p = 0.000) (Table 2).

The most fractured maxillofacial bone was mandible with 47.4% followed by maxilla with 26.6% and zygoma with 16.5% respectively in both genders. Other distributions were as shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Within the mandible, the body was the most fractured site with 103 (10.2%) cases followed by angle with 100 (9.9%), symphysis with 87 (8.6%) and condyle with 79 (7.8%) in the descending order of frequency.

Within the maxilla, Le Fort I fractures were the commonest with 70 (7.0%) cases followed by Le Fort II with 60 (6.0%) cases, while zygomatic body fractures with 228 (22.6%) cases, were the most common of the zygomatic complex. Isolated orbital floor fracture was observed to be the most prevalent of the orbital fractures with 38 (3.8%) cases while fractures of both inner and outer plates were observed in 6 (0.6%) cases. Other distributions were as shown in Table 3.

Majority of the maxillofacial fractures were simple fractures (84.1%), while 160 (15.9%) were comminuted. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with titanium plates and screws was the most common treatment modality and was used in 814 (80.8%) cases with statistically significant difference (Table 4). Other treatment options used in the management of the maxillofacial bone fractures were as shown in Table 3.

Discussion

Maxillofacial trauma is a serious public health drawback in Saudi Arabia [2]. They inflict a major public health burden regarding workload, treatment cost, psychological effects and overall poor health-related quality of life on the victims [12-15].

The epidemiology of maxillofacial injuries varies between and within the populations studied. This disparity occurs between nations, and in the different provinces of the same country. Factors like topography of the regions, cultural background, socio-economic status, population density and the time of the year, can greatly influence the type and distribution of oral and maxillofacial injuries [7,16-18]. Several studies have investigated the epidemiology of maxillofacial injures in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in different provinces such as Al-Medina [19], Riyadh [7,20], Aseer [1], Makkah [21] and Jeddah [22]. None has been reported in Najran region hence the justification for the current study.

A huge majority of victims in this study were males (96.6%) with a M:F 29:1. This is far-off higher than studies done in Taiwan (71.3%) M:F 7:1 [23], India (83.5%) 8.1:1 [24] and Iran (89.3%) M:F 8.4:1) [25]. In the Kingdom, despite the widely reported male preponderance in other studies, no higher male to female ratio as compared to the current study, has ever been reported. In the Aseer province, which is also in the same southern region like Najran, a similar high male preponderance was reported 91.1% with a M:F 10:1 [1]. The southern region of Saudi Arabia constitutes a very conservative and cultural population such that females spend more time at home with little or no outdoor activities while the males spend more time in motor vehicles as means of transport and entertainment [1]. On the contrary, lower M:F has been reported in Austria [26] and Canada [27] (2.1:1 and 1.6:1, respectively) where females in those nations aggressively participate in social activities therefore more predisposed to RTA, in addition to urban violence.

Young adults between the ages of 20-40 years constitute the majority of victims in the current study, accounting for 88.3% of the study population. Similar observations were reported in several other studies and countries [4,28-32] where bodily activities and movement, seen in this age bracket, have been responsible for this trend. Furthermore, aspiration for self-autonomy, high social passion, reckless driving, exposure to other high-risk events and sometimes, substance abuse in some countries, were also responsible for the high prevalence of maxillofacial injuries during this age bracket [4]. Frequently, the patient is injured while driving fast and not wearing seat belt. Another factor is good roads and fast cars in the hands of young drivers. Increase use of cellphones, texting while driving resulting in reduced concentration in driving and contribute to RTAs [23].

Globally, RTA especially MVA remain the major cause of maxillofacial injuries including Saudi Arabia [3,5,18]. In other less developed world, motorcycle related RTA has been the main etiological factor [22,33,34]. In our study and other studies from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, no motorcycle-related RTA was observed. This can be attributed to absence of use of motorcycles for commercial activities in the Kingdom. Majority of the citizens and residents have access to cars either as rented or privately-owned especially by the very young people [4]. However, this is in contrast to some parts of the developing world where motorcycles are the major means of transportation therefore most of the RTA-related maxillofacial injuries are attributed to them [33]. Furthermore, most of these motorcycle riders and passengers don't wear protective helmets to protect the head and neck region from injuries [23,33]. As motorcycle use is increasing among the youth in the Kingdom, crash helmet and body protection should be mandatory for the riders [23].

According to a report by Almasri, et al. 2015 [23], the severity and pattern of maxillofacial fractures can be attributed to the mechanism of injuries which are mainly due to the lower energy RTA at the city area compared to a higher energy injury in some mountainous regions such as the southern province of Najran which produces more severe injuries. The southern province is a mountainous region with many individuals living in smaller cities and villages mainly located in the mountainsides and connected by intercity roads and residents frequently use pick-up vehicles to transport goods for families and farms [1]. Reckless driving, failure to follow traffic rules and sometimes, driving by unlicensed individuals also contribute heavily to the high incidence of RTA in the region [1].

In the Kingdom, despite strict traffic law enforcements and the commencement of SAHER system, there is still high prevalence of MVA as observed in current and other studies. The SAHER system is a computerized traffic control technique in Saudi Arabia which is a complete and well-equipped network of digital cameras and online monitoring system linked with the National Information Center of the Ministry of Interior [35]. It has a robust check on traffic flow through a satellite system and has special features such as auto vehicle location and identifications, variable message signs, closed-circuit TV, law enforcement system, and traffic management system [35]. In addition, this system needs no human resource for its functioning and works even more than a traffic warden [35]. Anecdotal findings have identified indiscriminate use of mobile phones as a major cause of the higher prevalence of MVA in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Although, this factor has not been properly investigated, it is high time it is looked into and appropriate measures put in place to check this danger. While, camera monitoring of use of mobile phones for calls and even messaging while driving, has recently been incorporated into the SAHER system, it is still too early to evaluate its effect on the incidence of RTA. Furthermore, Al-Shahwan, et al. [36] have recently validated an Arabic instrument on the Problematic Use of Mobile Phones (PUMP) among the University students. This study should be given wider coverage in the Kingdom in order to identify this danger and its relationship with the persistently higher prevalence of MVA despite good roads and strict traffic control system.

Fall was observed as the second most frequent etiology of maxillofacial injuries, after MVA, in the current study. This was most common in the elderly and some young adults. Similar findings have been reported in the Kingdom [4], however, in other studies, fall was reported as the main etiology of maxillofacial injuries [27,37,38]. Other etiologies of maxillofacial injuries such as assault/domestic violence, sports, occupational and animals were not very common in the current study. Females were not involved in injuries secondary to sports, industrial, animal nor street assaults because they are less exposed to such factors [4]. However, from the current study, three cases of maxillofacial bone fractures were observed that was related to domestic violence. Assault-related maxillofacial injuries may also be on the increase in the Kingdom, although not very common in the current study. In other climes, assault-related maxillofacial injuries constitute the highest etiological factor of maxillofacial injuries [39,40].

In both genders, the mandible was the commonest maxillofacial bone that was fractured during the study period (47.4%) and closely followed by the zygomatic bone (26.6%). The literature is very robust with similar research findings in Saudi Arabia and other climes [12,16,28,31,37,41,42]. On the contrary, some other studies have reported midface fractures as the commonest. For example, Cabalag, et al. [40] in Australia have reported Le-Fort and orbital floor fractures as the commonest, while in Italy, Arangio, et al. [30] reported zygomatic bone fractures as the most observed. In Korea, Lee, et al. [39] have reported nasal bones as the most frequently fractured maxillofacial bone.

Different mechanisms of injuries may have been responsible for these variations. Nasal bone fractures were excluded from our study because they fall under the management of ENT which is strictly a hospital policy. Similarly, isolated naso-ethmoidal (NOE) fractures which were previously managed by the maxillofacial team was also moved to the ENT department hence the few cases, including those combined with other facial fractures, are reported in this current study. Furthermore, isolated frontal bone fractures were rare in our study with only 8 (0.3%) cases because most of the frontal bone fractures were associated with skull fractures and are, therefore being managed by the neurosurgery team and sometimes with collaboration from the maxillofacial surgery team.

The mandibular body was the commonest fracture location within the mandible (10.2%) in our study. This was similar to the study in Al-Madinah where body fracture was reported as the commonest [19]. There are wide variations of the commonest anatomical location of mandibular fractures reported within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The Para symphyseal fracture was reported as most prevalent in Riyadh [7], while another study reported angle fracture as most prevalent in the same city [20]. In our study, fracture of the body of mandible was the most common and angle fracture was the second most prevalent. However, in Aseer region, Almasri [1] reported condylar fractures as the most common followed by Para symphyseal fractures. Similarly, in Jeddah, condylar fracture was reported as most frequent [22]. This was in contrast to our study as condylar fractures were fourth most frequent. The higher frequency of condylar fractures have been attributed to the thin neck of the condyle which makes it to snap when forces are directed on it [43]. Symphyseal fractures were the third most common fractures in our series which was similar to a reported study [44]. However, this was in contrast to other studies in the Kingdom where the reported frequency of symphyseal fracture was much lower [1,4]. The frequency of ramus and coronoid fractures in our study was very low (2.3% and 0.7%) respectively, which is consistent with other studies in the Kingdom [1,4,7].

In the midface, zygomatic complex fracture was reported as the most common in our study (22.6%). This is in agreement to reported results internationally [16,30,41,45] and locally within the Kingdom [7,19,22]. However, our finding is at variance with study from Nwoku, et al. [20] in Riyadh where they reported Le Fort II fracture as the most frequent mid-face fracture. Orbital fractures were observed as the fourth most common maxillofacial bone fractures with majority presenting as isolated orbital floor fractures. Similar findings have been reported in the literature [5,11,46].

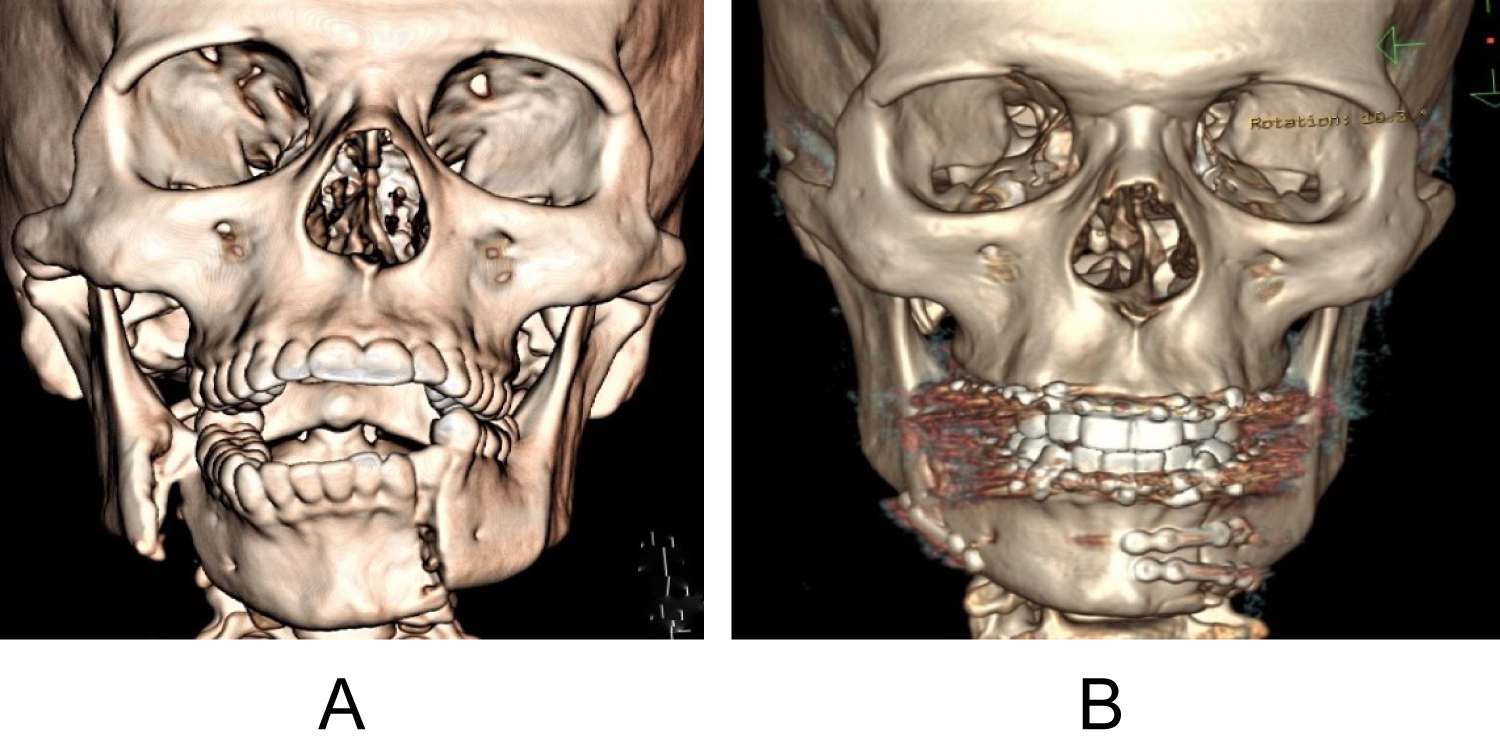

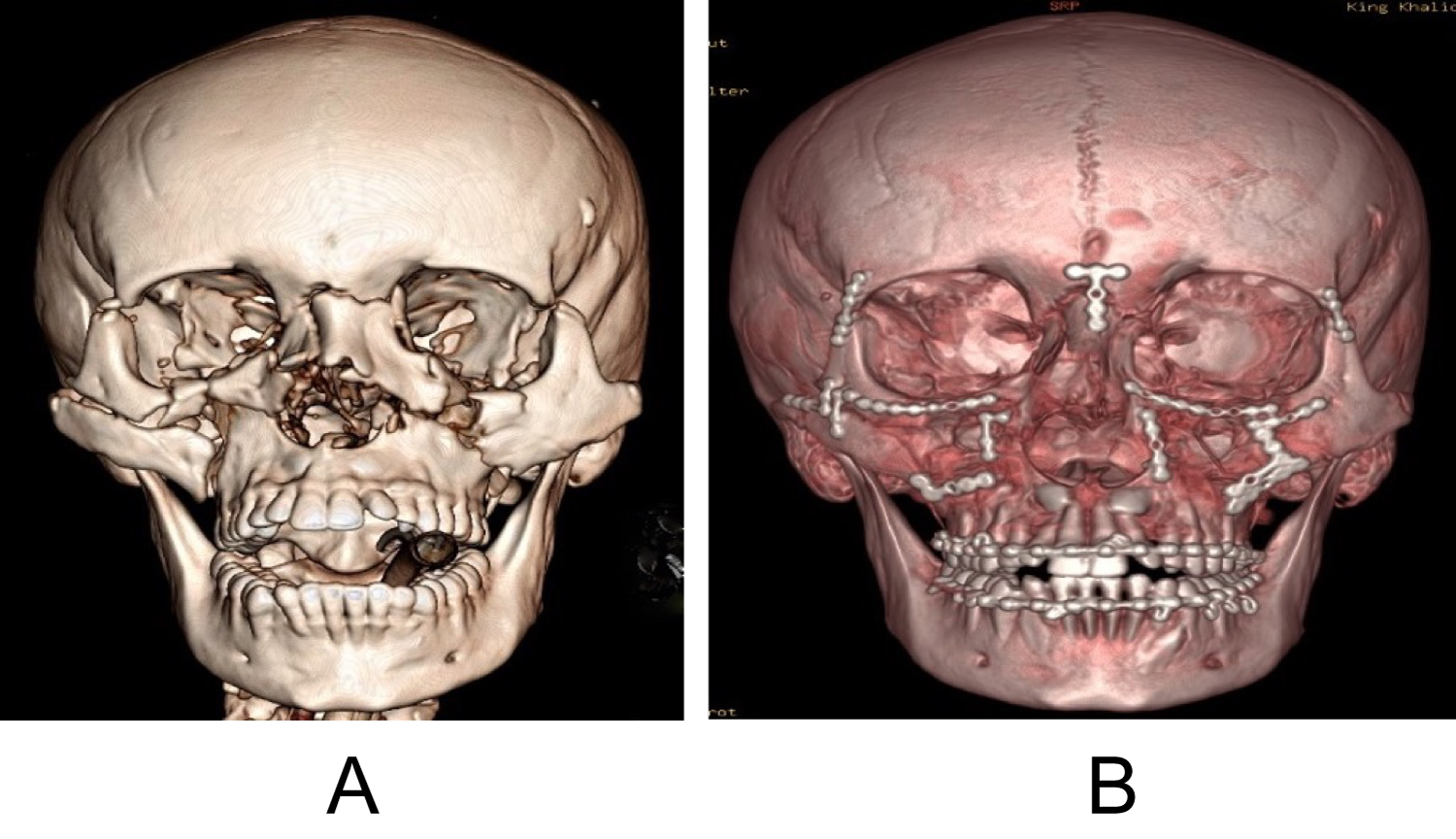

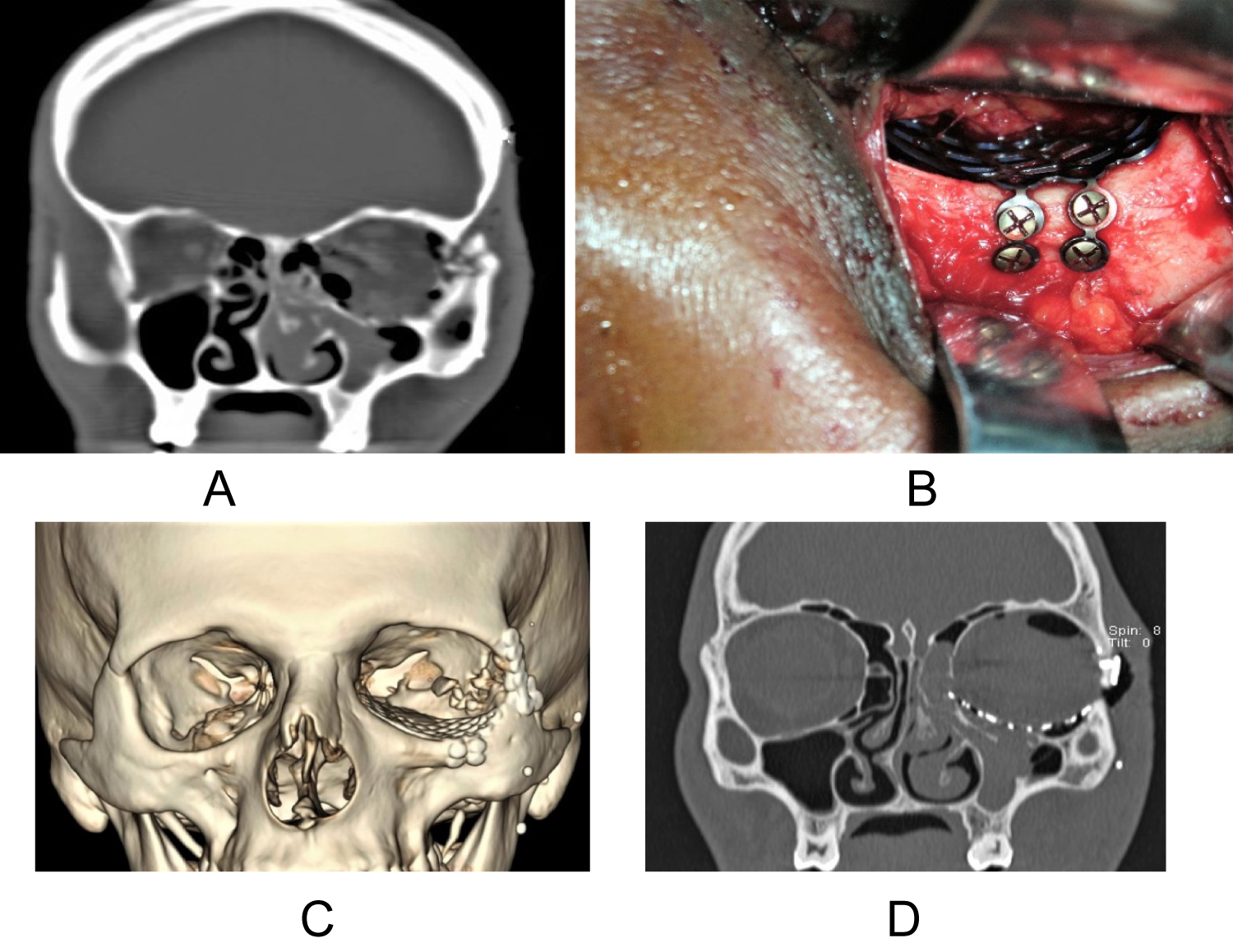

Maxillofacial fractures can be treated with either closed reduction, ORIF or a combination of these methods. The resolution regarding management depends upon a variety of factors such as nature of the injury, associated injuries, comorbid medical conditions, abilities of the surgeon, availability of facilities and instruments, and patient's ability to pay for the treatment cost [47]. In the developing world, cost of treatment and ability of patients to pay for hardware's is a major determining factor of treatment choice [47,48]. Our choice of treatment was not based on ability of patients to pay nor lack of facilities and equipments, it was based on nature of injury, associated injuries and comorbid conditions. In Saudi Arabia, healthcare is totally free with adequate provision of equipment including hardware. The majority of our cases (80.8%) were treated by ORIF using titanium plates and screws. In the mandible, Champy's principles of osteosynthesis was adopted with the use of 2.0 mm titanium plates and screws at the lower and upper borders (zones of tension and compression respectively) [49]. They suggest that when the plates are placed along the ideal lines of osteosynthesis, they give maximum stability and appropriate osteosynthesis necessary for healing (Figure 1). Larger load-bearing plates are used to provide absolute rigid fixation in comminuted fractures of mandible. For the midface fractures, plates ranging from 1.3 mm through 1.5 mm to 2 mm in size, depending on fracture sites, were deployed in the treatment. Usually a combination of ORIF and arch bars are used in the management of Le Fort level fractures of the maxilla (Figure 2). Defects resulting from orbital floor fractures were managed with orbital reconstruction plate or titanium mesh (Figure 3).

Conclusion

The results of our study showed overwhelming prevalence of the male gender over female and dominance of age group 20-30 years in the incidence of maxillofacial fractures. MVA was the main etiologic factor and ORIF was the principal treatment modality. The data has brought out information for appropriate health education programs and application of firmer traffic rules to reduce accidents. To minimize maxillofacial injuries and its physical and psychological impact on the society, more coordinated strategies for action by various actors are warranted including the issue of Problematic Use of Mobile Phones (PUMP). The use of seatbelts, observation of speed regulations and avoidance of use of cellphones for speaking or texting during driving will go a long way in reducing the incidence of MVAs. Emphasis on awareness must be made regarding safety rules which should be targeted at the high-risk groups, most of which are the economically productive age group.

References

- Almasri M (2013) Severity and causality of maxillofacial trauma in the Southern region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J 25: 107-110.

- Alqahtani A (2018) Patterns of maxillofacial fractures associated with assault injury in Khamis Mushait City and related factors. Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine 70: 325-328.

- Alghamdi S, Alhabab R, Alsalmi S (2017) The epidemiology, incidence and patterns of maxillofacial fractures in Jeddah city, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 16: 255.

- Al-Bokhamseen M, Salma R, Al-Bodbaij M (2019) Patterns of maxillofacial fractures in Hofuf, Saudi Arabia: A 10-year retrospective case series. Saudi DentJ 31: 129-136.

- Maliska MCS, Lima Júnior SM, Jose Nazareno Gil (2009) Analysis of 185 maxillofacial fractures in the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Brazilian Oral Research 23: 268-274.

- Girotto JA, MacKenzie E, Fowler C, et al. (2001) Long-term physical impairment and functional outcomes after complex facial fractures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 108: 312-327.

- Abdullah WA, Al-Mutairi K, Al-Ali Y, et al. (2013) Patterns and etiology of maxillofacial fractures in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. The Saudi Dental Journal 25: 33-38.

- Bali R, Sharma P, Garg A, et al. (2013) A comprehensive study on maxillofacial trauma conducted in Yamunanagar, India. J Inj Violence Res 5: 108-116.

- Fasola AO, Nyako EA, Obiechina AE, et al. (2003) Trends in the characteristics of maxillofacial fractures in Nigeria. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 61: 1140-1143.

- Braimah RO, Ibikunle AA, Taiwo AO, et al. (2016) Rare etiological factor of maxillofacial injury: Case series seen and managed in a tertiary referral centre. J Emerg Trauma Shock 9: 81-84.

- Udeabor SE, Akinmoladun VI, Fasola OA, et al. (2012) Trends in the aetiology of middle third facial injuries in southwest Nigeria. Oral Surgery 5: 7-12.

- Boffano P, Kommers SC, Karagozoglu KH, et al. (2014) Aetiology of maxillofacial fractures: A review of published studies during the last 30 years. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 52: 901-906.

- Braimah RO, Ukpong DI, Ndukwe KC, et al. (2017) Comparative study of anxiety and depression following maxillofacial and orthopedic injuries. Study from a Nigerian University Teaching Hospital Clin Exp Dent Res 3: 215-219.

- Braimah RO, Ukpong DI, Ndukwe KC, et al. (2018) Self-esteem following maxillofacial and orthopedic injuries: preliminary observations in sub-Saharan Africans. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Oral Maxillofac Surg 23: 71-76.

- Braimah RO, Ukpong DI, Ndukwe KC, et al. (2018) Health-related quality of life in Nigerian patients following maxillofacial and orthopedic injuries: A comparative study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 10: 49-53.

- Al-Khateeb T, Abdullah FM. (2007) Craniomaxillofacial injuries in the United Arab Emirates: A retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65: 1094-1101.

- Gandhi S, Ranganathan LK, Solanki M, et al. (2011) Pattern of maxillofacial fractures at a tertiary hospital in northern India: a 4-year retrospective study of 718 patients. Dent Traumatol 27: 257-262.

- Hogg NJ, Stewart TC, Armstrong JE, et al. (2000) Epidemiology of maxillofacial injuries at trauma hospitals in Ontario, Canada, between 1992 and 1997. The Journal of Trauma 49: 425-432.

- Rabi AG, Khateery SM (2002) Maxillofacial trauma in Al Madina region of Saudi Arabia: A 5-year retrospective study. Asian Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 14: 10-14.

- Nwoku AL, Oluyadi BA (2004) Retrospective analysis of 1206 maxillofacial fractures in an urban Saudi hospital: 8 year review. Pakistan Oral Dent. J 24: 13-16.

- Almasri M, Amin D, Aboola AF, et al. (2015) Maxillofacial fractures in Makka City in Saudi Arabia: An 8-year review of practice. Am J Public Heal Res 3: 56-59.

- Jan A, Alsehaimy M, Al-Sebaei M, et al. (2015) A retrospective study of the epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Am Sci 11: 57-61.

- Liang C, Liu H, Rau C, et al. (2015) Motorcycle-related hospitalization of adolescents in a Level I trauma center in southern Taiwan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr 15: 105.

- Verma V, Singh A, Singh GK, et al. (2017) Epidemiology of trauma victims admitted to a level 2 trauma center of North India. Int J CritIllnInj Sci 7: 107-112.

- Hosseinpour M, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, EsmaeilpourAghdam M, et al. (2017) Trend and seasonal patterns of injuries and mortality due to motorcyclists traffic accidents: A hospital-based study. Bull Emerg Trauma 5: 47-52.

- Gassner R, Tuli T, Hächl O, et al. (2003) Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: A 10 year review of 9543 cases with 21067 injuries. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg 31: 51-61.

- Al-Dajani M, Quinõnez C, Macpherson AK, et al. (2015) Epidemiology of maxillofacial injuries in Ontario, Canada. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 73: 693.e1-693.e9.

- Van Den Bergh B, Karagozoglu KH, Heymans MW, et al. (2012) Aetiology and incidence of maxillofacial trauma in Amsterdam: A retrospective analysis of 579 patients. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg 40: e165-e169.

- Mijiti A, Ling W, Tuerdi M, et al. (2014) Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures treated at a university hospital, Xinjiang, China: A 5-year retrospective study. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg 42: 227-233.

- Arangio P, Vellone V, Torre U, et al. (2014) Maxillofacial fractures in the province of Latina, Lazio, Italy: Review of 400 injuries and 83 cases. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg 42: 583-587.

- Adebayo ET, Ajike OS, Adekeye EO (2003) Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Kaduna, Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 41: 396-400.

- Mabrouk A, Mohamed AR, Mahmoud N (2014) Incidence, etiology, and patterns of maxillofacial fractures in ain-Shams University, Cairo, Egypt: A 4-Year retrospective study. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr 7: 224-232.

- Oginni FO, Ugboko VI, Ogundipe O, et al. (2006) Motorcycle-related maxillofacial injuries among Nigerian intracity road users. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 64: 56-62.

- Cavalcanti AL, Ferreira FHC, Olinda RA, et al. (2017) Motorcycle-Related Cranio-Maxillofacial Injuries among Brazilian Children and Adolescents. Biomed Pharmacol J 10: 1603-1609.

- Ministry of Interior. Saher System of Traffic Regulations in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

- Alshahwan H, Alosaimi FD, Alyahya H, et al. (2020) Arabic validation of Problematic Use of Mobile Phone scale among university students in Saudi Arabia. J Nat Sci Med 3: 101-106.

- Motamedi MHK, Dadgar E, Ebrahimi A, et al. (2014) Pattern of maxillofacial fractures :A 5-year analysis of 8,818 patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 77: 630-634.

- Sasaki R, Ogiuchi H, Kumasaka A, et al. (2009) Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial fracture by five departments in Tokyo: A Review of 674 cases. Oral Sci Int 6: 1-7.

- Lee JH, Cho BK, Park WJ (2010) A 4-year retrospective study of facial fractures on Jeju, Korea. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg 38: 192-196.

- Cabalag MS, Wasiak J, Andrew NE, et al. (2014) Epidemiology and management of maxillofacial fractures in an Australian trauma centre. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 67: 183-189.

- Brasileiro BF, Passeri LA (2006) Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures in Brazil: A 5-year prospective study. Oral Surg Oral MeOral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 102: 28-34.

- Kostakis G, Stathopoulos P, Dais P, et al. (2012) An epidemiologic analysis of 1,142 maxillofacial fractures and concomitant injuries. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 114: S69-S73.

- Lee CW, Foo QC, Wong LV, et al. (2017) An overview of maxillofacial trauma in oral and maxillofacial tertiary trauma centre, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 10: 16-21.

- Kyung-Pil P, Seong-Un L, Jeong-Hwan K, et al. (2015) Fracture patterns in the maxillofacial region: A Four-year retrospective study. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 41: 306-316.

- Mesgarzadeh AH, Shahamfar M, Azar SF, et al. (2011) Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial fractures in north western of Iran: A Retrospective study. J Emerg Trauma Shock 4: 48-52.

- AlHammad Z, Nusair Y, Alotaibi S, et al. (2019) A cross-sectional study of the prevalence and severity of maxillofacial fractures resulting from motor vehicle accidents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dental Journal.

- Chalya PL, Mchembe M, Mabula JB, et al. (2011) Etiological spectrum, injury characteristics and treatment outcome of maxillofacial injuries in a Tanzanian teaching hospital. J Trauma Manag Outcomes 5: 7.

- Ibikunle AA, Taiwo AO, Braimah RO, et al. (2016) Changing pattern in the treatment of mandibular fractures in North-Western Nigeria. Afr J Trauma 5: 36-42.

- Champy M, Lodde JP, Schmitt R, et al. (1978) Mandibular Osteosynthesis by Miniature Screwed Plates via a Buccal Approach. J Maxillofac Surg 6: 14-21.

Corresponding Author

Dr. Ramat Oyebunmi Braimah, BDS, FAOCMF, FMCDS, FWACS, Specialist, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Specialty Regional Dental Center, Najran, Saudi Arabia.

Copyright

© 2020 Antonella C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.