The Forgotten Epidemic: A Niagara Health System Initiative to Reduce Postoperative Opioid Consumption

Abstract

Background: Opioid over-prescription is a great driver in the opioid epidemic, and there is significant variability in post-surgical prescriptions. This paper describes a large-scale quality improvement campaign at the Niagara Health System (NHS) to reduce postoperative opioid prescriptions.

Methods: This prospective study was conducted using a Plan-Do-Study-Act Methodology (PDSA) with the primary aim to improve postoperative opioid prescribing patterns at the NHS and reduce the number of opioids prescribed. 436 patients undergoing a same-day elective surgery linked to over-prescription of postoperative opioids in previous literature were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included patients younger than 18, pregnancy, and a history of opioid use. Initially, participants provided consent and completed a questionnaire. 10-14 days later, patients were contacted to determine prescription opioid use. We implemented two prescription reduction strategies: PDSA cycle 1 included multi-disciplinary educational sessions, and PDSA cycle 2 included redesigned patient handouts. Subsequently, trained reviewers remeasured the baseline by abstracting patient data from medical records to compare postoperative prescriptions with the baseline data following the interventions. This study received an exemption from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board.

Results: The baseline study determined that, on average, there was a -66.44% change in the number of opioids consumed by patients compared to those prescribed (p = 0.008). Overall, although not statistically significant, there was a 21.02% reduction in the number of postoperative opioids prescribed compared to baseline following the interventions (p = 0.492). There were also significant localized reductions in the following surgeries: Hand/joint (-64.25%, p = 0.0454), laparoscopic or open hernia repair (-43.56%, p = 0.0004), ureteroscopy (-65.00%, p = 0.0013), septoplasty (-76.69%, p = 0.0261), cholecystectomy (-34.09%, p = 0.0027), and tonsillectomy (-85.97%, p = 0.0005).

Interpretation: This is the first large-scale Canadian study to demonstrate the efficacy of prescription reduction strategies in a postoperative context in community hospitals. Future study modifications could include larger sample size and targeted approaches for individual studies.

Background

Canada ranks second to the USA in per capita consumption of prescription opioids [1,2]. In the past twenty-five years, opioid-related deaths in Ontario have increased four-fold [3]. In 2016, 1 in 3 opioid-related deaths occurred among Ontarians with active opioid prescriptions, and 40% of emergency department (ED) visits for opioid overdose had an active prescription [4]. Despite media awareness campaigns, the number of opioid prescriptions grew in the last three years, and in Ontario, physicians represent 97% of opioid prescribers [1]. Previous Canadian and American studies demonstrated that physicians play a large role in opioid prescribing, leading to long-term and recurrent use in opioid-naïve patients [5,6]. For instance, an Ontario study determined that opioid-naïve patients who were prescribed opioids within 7 days post-ambulatory surgery were 44% more likely to become long-term opioid users within 1-year compared to those not receiving a prescription [6]. A large number of overdose deaths can also be linked to postoperative opioid prescriptions.

Previous literature demonstrates variability in post-surgical opioid prescribing practices across specialties and between surgeons for the same procedure [7-10]. Ladha, et al. observed large differences between the USA and Canada concerning postoperative opioid prescription, suggesting local factors may also play a role [11]. Additionally, there is observed disparity in postoperative opioid consumption by patients; for instance, Hill, et al. reported that only 28% of prescribed opioids were taken by patients post-operatively [7]. These data support the need for prescribing guidelines.

Given these trends and lack of Canadian data, we embarked on a quality improvement campaign targeting postoperative opioid prescriptions. Previous studies have focused on select surgeries and specialties. This is the first large-scale Canadian study evaluating fourteen different surgeries across multiple specialties that have previously been associated with over-prescription of opioids in literature [12]. To our knowledge, few previous studies have included "community" hospitals, and studies have demonstrated that often there is no formal teaching given to residents on prescribing opioids post-operatively [13]. Our study focuses on a community site, the Niagara Health System (NHS), where primarily staff physicians write prescriptions. This study aims to improve opioid prescription strategies post-operatively at NHS and reduce the number of opioids prescribed post-operatively by 50% over one year through holding multi-disciplinary educational seminars and developing standardized, patient-specific, postoperative opioids and multimodal analgesia usage handouts. A secondary aim is to improve opioid prescription strategies post-operatively in NHS by identifying and ultimately mitigating the discrepancy between the number of opioids prescribed by physicians and the amount taken by patients.

Methods

Ethics approval

Given that this is a quality improvement (QI) project designed to address local opioid prescription patterns within the NHS, this study was granted an exemption from ethics review by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (HiREB).

Study design

This prospective study was conducted using a Plan-Do-Study-Act Methodology (PDSA) with the primary aim to improve postoperative opioid prescribing patterns in the NHS and reduce the number of opioids prescribed by NHS surgeons. Patients receiving selected elective day surgeries at all three NHS sites, including the Well and Hospital, Greater Niagara General Hospital and the St. Catharines General Hospital, were included in this prospective quality improvement study. These three hospitals are community teaching sites for the McMaster University Niagara Regional Campus, with approximately 32000 elective day surgeries per year for 2018/2019 [14]. The specific surgeries included in this study have been previously associated with the over-prescription of opioids in literature [12]. Table 1 displays the number of patients per surgery, both pre- and post-interventions. A total of 436 patients were included in the study, and no financial compensation was provided to participants. Participants whose charts had incomplete information, such as a lack of a photocopied prescription or incomplete contact information, were excluded from the study.

Establishing baseline

From March 2019 to June 2019, baseline opioid prescribing and usage patterns were measured post select elective day surgeries. Voluntary informed consent was obtained from patients meeting inclusion criteria. Nurses documented qualifying and consenting patients' details. Participants who provided consent were given a questionnaire to establish preoperative prescription use. Two medical students conducted telephone interviews 10 to 14 days post-operatively to establish opioid use patterns. Exclusion criteria included patients who were less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, pregnant, any history of opioid use or chronic pain, or who did not answer their phone after three attempts of calling. The primary outcome was to prospectively measure the number of opioid medications prescribed and consumed post-operatively and whether there was a difference between opioids prescribed and consumed.

Interventions implemented

Two strategies were implemented to reduce postoperative opioid prescribing patterns. In PDSA cycle 1, Educational sessions disclosing the baseline study results were held with nurses, surgeons, and other stakeholders to disseminate the results and provide safe prescribing education. In PDSA cycle 2, patient handouts, including information about the World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder and multimodal analgesia techniques, were attached to patient surgical packages. This information was also disseminated to patients by nurses verbally. Initially, PDSA cycle 3 included long-term plans to alter postoperative order sets to include multimodal analgesic options; however, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the cancellation of elective surgical procedures, this was postponed.

Determining change

By November 2020, given increased infection transmission concerns due to COVID-19, the postoperative prescriptions were uploaded electronically into patients' electronic medical records (EMRs). Two medical students independently abstracted patient data from patients' EMRs from November 2019, using Meditech. The number of opioid medications prescribed post-operatively after the elective day surgery procedures following the interventions was abstracted and compared to the baseline data.

Statistical analysis

The postoperative opioid prescription was converted into morphine milligram equivalents (MME) for standardization for each patient. The MME are reported ± standard deviation. The data was analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Two-tailed, two-sample t-tests assuming unequal variance were calculated for each elective surgical procedure included in this study to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between opioid prescribing and consumption patterns in the baseline study and in opioid prescribing patterns post-implementation of the interventions. A critical value of p < 0.05 was used to establish significance.

Results

Procedures and distribution

There were 256 patients included in the baseline study, and 180 patients were enrolled following the implementation of both PDSA cycles 1 and 2. Table 1 displays the number of patients undergoing each elective procedure. Of the 256 patients in the baseline study, the majority of the patients underwent Laparoscopic or Open Hernia Repair (15.6% of total patients enrolled), followed by Cholecystectomy (14.8%) and Dental Extraction (9.8%), and the least number of patients (n = 1) underwent Total shoulder repair (0.4%). Of the 180 patients enrolled following the implementation of the interventions, the majority of the patients underwent Knee Arthroscopy/Meniscectomy (16.1%), followed by Ureteroscopy (14.4%) and Breast (Lumpectomy, Mastectomy ± sentinel node biopsy (SNB)) (12.8%). The least number of patients (n = 1) underwent Dilatation & Curettage (0.6%). Of note, following the PDSA cycles, there were only two patients who underwent each of the following surgeries: Arteriovenous (AV) Fistula (1.1%) and Varicose Veins (1.1%).

Determining baseline opioid prescribing and usage patterns

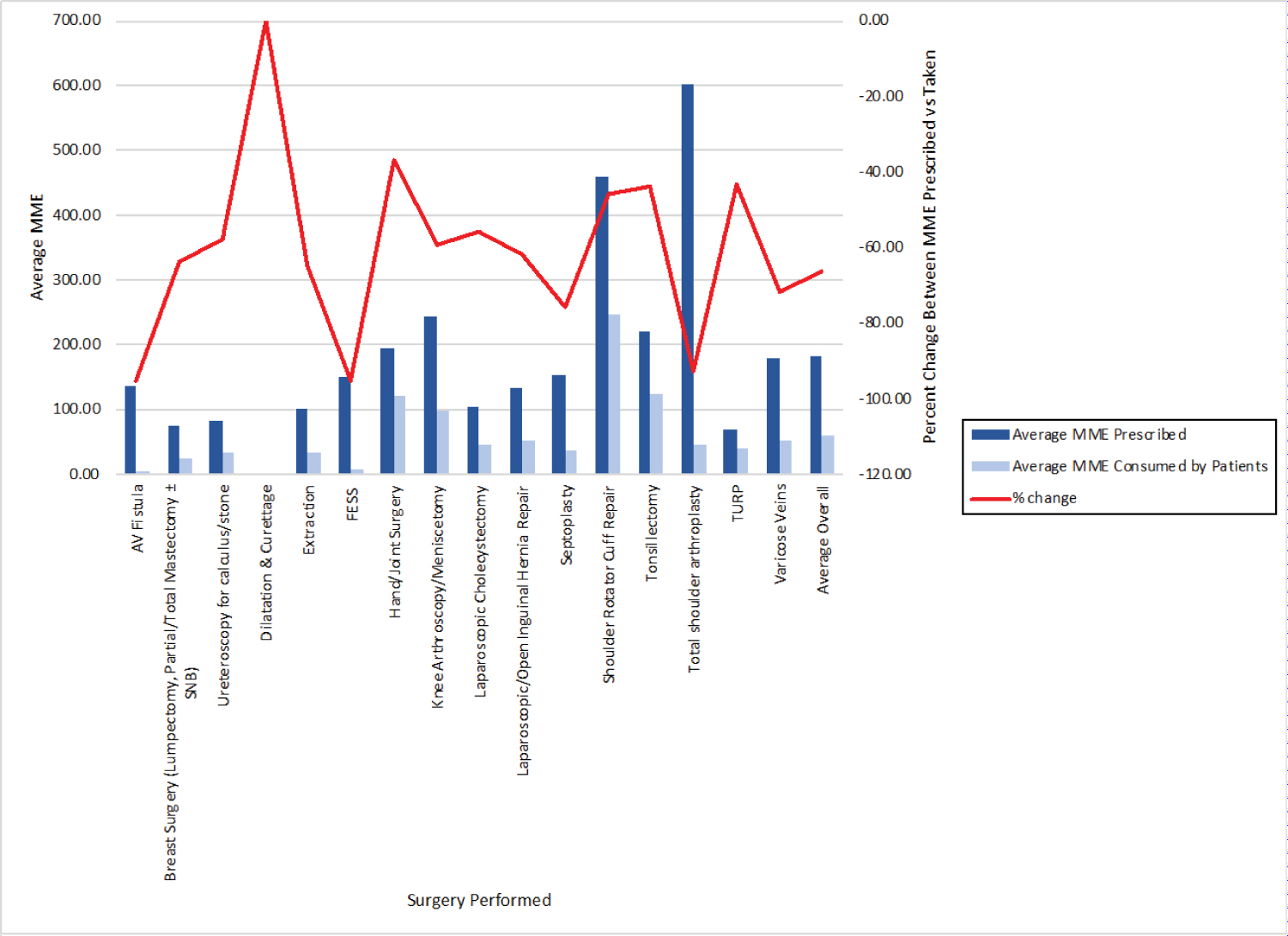

Table 2 outlines the pre-intervention opioid prescribing and usage patterns and the percentage of opioids used compared to those prescribed. Surgeries with the most opioids prescribed were total shoulder repairs (600.00 MME however, n = 1), shoulder rotator cuff repairs (458.26 ± 230.11 MME), followed by Knee Arthroscopies/Meniscectomies (242.50 ± 111.33 MME) and tonsillectomies (220.91 ± 126.81 MME). The least number of opioids prescribed post-operatively were following Dilatation & Curettage (0.00 ± 0.00 MME). In terms of opioid consumption, most opioids were consumed following shoulder rotator cuff repair (247.30 ± 209.50 MME), a -46.03% change from the amount prescribed by surgeons (p = 0.002). This was followed by tonsillectomies (124.55 ± 103.05 MME, which was -43.62% different than the amount prescribed, p = 0.065) and hand/joint surgery (121.56 ± 103.20 MME, which was a -37.01% difference from the amount prescribed, p = 0.274). The least number of opioids consumed post-operatively were following AV Fistula surgeries (6.43 ± 8.56 MME, which was -95.24% different than the amount prescribed, p = 0.00004).

Overall, on average, surgeons prescribed 181.31 ± 151.05 MME of opioids, and patients consumed 60.85 ± 61.96 MME of opioids (-66.44% change, p = 0.008). The average amount of opioids consumed by patients post-operatively were 42.54% of those prescribed (Figure 1). There was a statistically significant change in the amount prescribed by surgeons compared to the amount consumed by patients following all the surgeries examined, excluding dilatation & curettages (as no opioids were prescribed), hand/joint surgery, tonsillectomies, total shoulder repairs (as n = 1), and transurethral resections of the prostate (TURPs). The greatest statistical difference in the number of opioids prescribed compared to the amount taken post-operatively was after AV fistula surgery (-95.24%, p = 0.0000421), followed by functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) (-95.00%, p = 0.0116492) and septoplasty (-75.56%, p = 7.27135x10-9). There was the least statistically significant percent change in the average MME of opioids consumed following cholecystectomies (-55.97%, p = 0.000002), followed by ureteroscopies for calculus/stone (-57.86%, p = 0.003) and knee arthroscopies/meniscectomies (-59.28%, p = 0.0004).

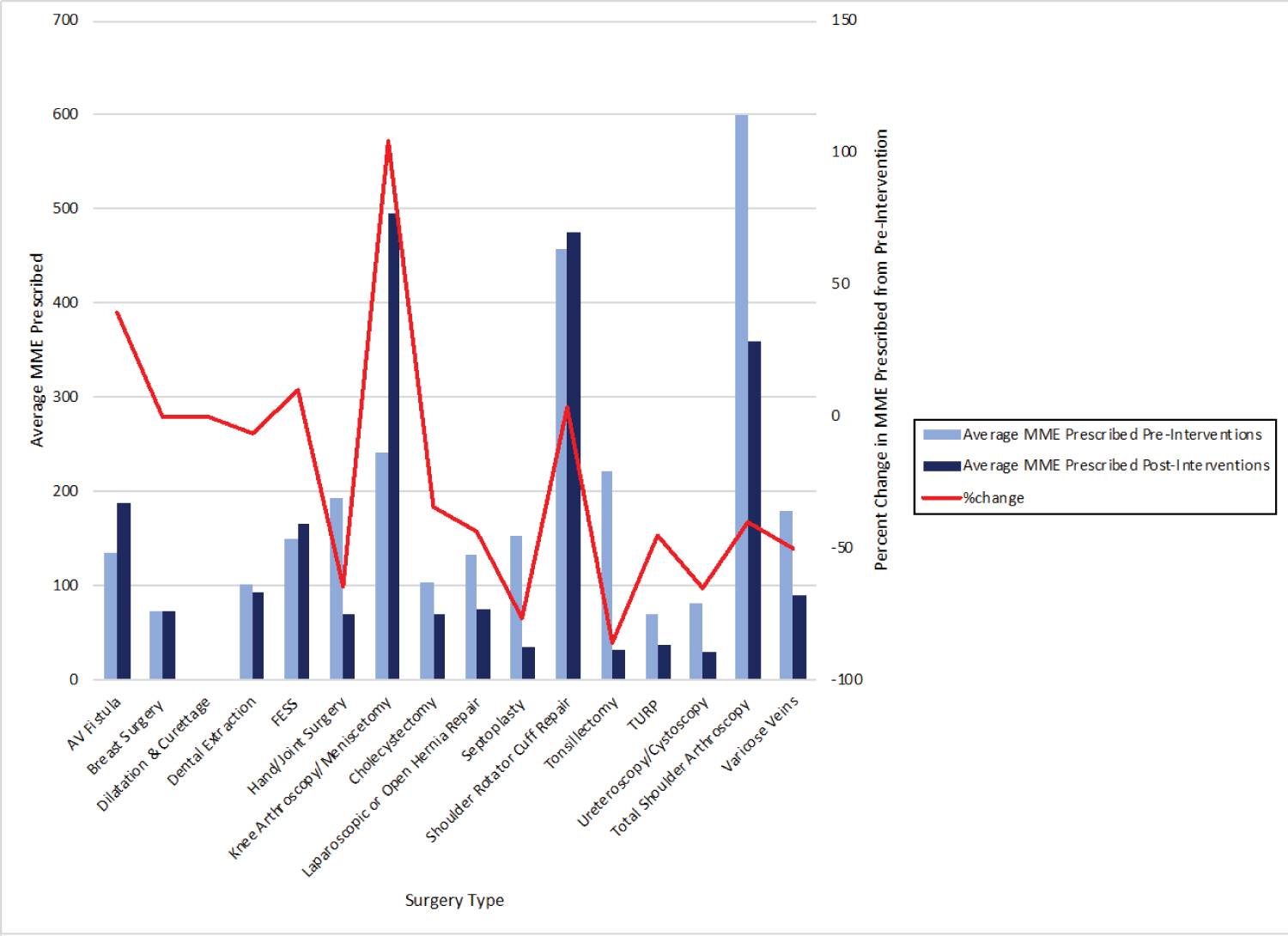

Determining change and outcomes of interventions implemented in PDSA cycles 1 and 2

Although not statistically significant, there was a clinically relevant 21.02% reduction in the average amount of opioids prescribed post-operatively following PDSA cycles 1 and 2 compared to baseline (p = 0.492). The mean MME of opioids prescribed following both PDSA cycles was 143.2 ± 158.83 MME, compared to the baseline of 181.31 ± 151.05 MME (-21.02% change, p = 0.49) (Table 3). A summary of the average amount of MME prescribed post-operatively after implementing the strategies, compared to before implementation, for each surgical procedure is demonstrated in Figure 2 and Table 3.

In particular, following both PDSA cycles, there was a statistically significant reduction in postoperative opioid prescribing select surgical procedures across multiple specialties (Table 3). The maximum reduction in postoperative opioid prescriptions was following tonsillectomies (-85.97% change, p = 0.0005). This was followed by, in descending order: Septoplasty (-76.69% change, p = 0.0261), ureteroscopy (-65.00% change, p = 0.0013), hand/joint surgery (-64.25%, p = 0.0454), laparoscopic or open hernia repair (-43.56%, p = 0.0004), and lastly cholecystectomy (-34.09%, p = 0.0027).

Notably, there was a statistically significant increase in postoperative opioid prescribing following Knee Arthroscopy/Meniscectomy (104.52% change, p = 0.00002). Although not significant, there was also a 3.37% increase in postoperative opioid prescriptions following shoulder rotator cuff repairs. These results should be revisited to understand prescribing patterns better within orthopedics and postoperative pain management among these patients. Specifically, the potential for a reduction in MME prescribed should be addressed as it appears to a potentially modifiable factor. The baseline study determined that there was a -46.03% change (p = 0.002) and -59.28% change (p = 0.0004) in the amount of narcotic consumed by patients compared to those prescribed following shoulder rotator cuff repair and knee arthroscopies/meniscectomies, respectively.

Overall, it appeared there was a statistically significant reduction in postoperative opioid prescribing in surgeries performed by general surgeons in specific as well, including the following: Laparoscopic or Open Hernia Repair (-43.56% change, p = 0.0004) and Cholecystectomy (-34.09% change, p = 0.0027). This may also be attributed to a province-wide campaign aimed at general surgeons specifically to reduce postoperative prescribing of opioids during the same time as this study.

Discussion

A statistically significant drop in postoperative opioid prescribing for select surgical procedures following our interventions was observed. Providing multi-disciplinary education sessions and distributing postoperative opioid discharge instructions to patients was effective in the context of the following procedures: Hand/joint, laparoscopic or open hernia repair, cholecystectomy, ureteroscopy, septoplasty and tonsillectomy. While the overall reduction across all surgeries was not statistically significant, there may be a clinically significant decrease in postoperative opioid prescribing in the NHS. A potential reduction of 21.02% from an average 181.3 ± 151.05 MME prescribed post-operatively could represent a decrease of 1.2 million MME prescribed to patients when multiplied across 32000 elective day surgeries annually. These results are timely given the surge of opioid-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada [15]. While deaths due to illicit drugs decreased since 2019, an increase in deaths has been noted in BC during the pandemic, with over 80% of these deaths attributed to opioid use [12]. Our study is highly relevant and well-timed as a reduction in postoperative opioid prescribing will directly impact reducing the number of opioids available for misuse, diversion, and overdoses.

The existence of variability in the number of opioids prescribed post-surgically across procedures [7,12] highlights the need to establish evidence-based guidelines for postoperative opioid prescribing. Variability also exists in postoperative opioid consumption by patients [9,10]. Feinberg, et al. reported that up to 59.1% of opioids were used post-operatively, while Bicket, et al. reported 67-92% of patients reported unused opioids post-operatively [9,10]. The leftover pills pose risks for diversion, misuse and improper disposal as patients were unsure of proper opioid disposal methods [9]. A recent study from Oakville, Canada, presented a newly developed three-phase integrated systems approach for pain management for ambulatory surgeries, which substantially reduced postoperative opioid prescribing [16]. They included preoperative, intra-operative and postoperative modifications to optimize pain management and decrease narcotic prescriptions. To our knowledge, this study is the first investigation of postoperative prescribing patterns in Canada at a community site, which diversifies the literature while also contributing to the growing body of research. Ladha, et al. highlighted differences between prescribing patterns in Canada, the USA, and Sweden, recognizing the need for country-specific guidelines [11]. Canada and the USA had a seven-fold higher rate of opioid prescriptions being filled post-operatively than Sweden, reinforcing the idea that opioid prescribing patterns are multidimensional. Investigating societal and cultural factors may be necessary to understand prescribing practices and should be studied further. Our study was conducted at a community site with primarily staff physicians writing prescriptions. A Yale University study demonstrated that residents are not always given formal teaching on prescribing opioids post-operatively [13]. Consequently, trainees learn to associate a particular prescription to particular procedures, which may lead to over-prescription. This potential confounder was avoided in our study. Furthermore, our study can contribute to evidence-based guidelines for postoperative analgesia prescription order sets. This will facilitate adequate analgesia for patients while also decreasing the risks associated with opioid use, including improper pain management, using extra opioids to mask surgical complications, developing an opioid use disorder, diversion or improper disposal of the opioids.

Our study's limitations include heterogeneity between sample sizes across the various surgeries. This may contribute to biases in our data as certain specialties may have developed particular preferences concerning postoperative opioid prescribing that would not be evident during analysis. Our intervention was not statistically significant across all surgeries among the various specialties begging the question of why the outcome was different among certain types of surgeries than others.

The amount of MME prescribed following orthopedic procedures appears to have increased post-intervention, specifically after rotator cuff repairs and knee arthroscopies/meniscectomies. Existing literature demonstrates that departmental guidelines may reduce opioid prescription, specifically in orthopedic procedures [17]. This is an important area to investigate further as data illustrates that patients undergoing orthopedic surgery are at potentially elevated risk for developing opioid use disorder [18].

Future directions include larger sample size and exploring targeted approaches to optimize our strategy to reduce postoperative opioid prescribing. For instance, the role of regional anesthesia and multimodal analgesia in reducing postoperative opioid prescriptions in orthopedic surgeries should be explored. Long-term, we plan to alter postoperative order sets to include multimodal analgesic options; this was put on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the cancellation of elective surgical procedures. Future studies should also determine whether there were significant differences in patient satisfaction and pain scores with reduced postoperative opioid prescriptions and whether improving discharge instructions altered patients' behaviours regarding narcotic disposal methods.

Not with standing these limitations, our study demonstrates a decrease in opioid prescriptions in the postoperative setting among various procedures and specialties following increased interdisciplinary education and disseminating improved discharge information and instructions. Pending validation in a larger setting, this data provides insight into mitigating physician contribution to the opioid crisis during a time that it is highly warranted.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

All the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Health Quality Ontario. Starting on Opioids.

- Opioid Prescribing in Canada - CIHI.

- Interactive Opioid Tool.

- Gomes T, Khuu W, Martins D, et al. (2018) Contributions of prescribed and non-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: Population based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ 362: 3207.

- Hoppe JA, Kim H, Heard K (2015) Association of emergency department opioid initiation with recurrent opioid use. Annals of Emergency Medicine 65: 493-499.

- Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, et al. (2012) Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery. Archives of Internal Medicine 172: 425-430.

- Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, et al. (2017) Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg 265: 709-714.

- Neuman MD, Bateman BT, Wunsch H (2019) Inappropriate opioid prescription after surgery. Lancet 93: 1547-1557.

- Feinberg AE, Chesney TR, Srikandarajah S, et al. (2018) Opioid use after discharge in postoperative patients: A Systematic review. Ann Surg 267: 1056-1062.

- Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, et al. (2017) Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: A systematic review. JAMA Surg 152: 1066-1071.

- Ladha KS, Neuman MD, Broms G, et al. (2019) Opioid prescribing after surgery in the United States, Canada, and Sweden. JAMA Netw Open 2: e1910734.

- Thiels CA, Ubl DS, Yost KJ, et al. (2018) Results of a prospective, multicenter initiative aimed at developing opioid-prescribing guidelines after surgery. Ann Surg 268: 457-468.

- Chiu AS, Healy JM, Dewane MP, et al. (2018) Trainees as agents of change in the opioid epidemic: Optimizing the opioid prescription practices of surgical residents. Journal of Surgical Education 75: 65-71.

- Patient Care Statistics.

- Tyndall M (2020) Safer opioid distribution in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Drug Policy 83: 102880.

- Rozario D (2020) A systems approach to the management of acute surgical pain and reduction of opioid use: The approach of oakville trafalgar memorial hospital. Canadian Journal of Surgery 63: E606-E608.

- Stepan JG, Lovecchio FC, Premkumar A, et al. (2019) Development of an institutional opioid prescriber education program and opioid-prescribing guidelines. J Bone Joint Surg Am 101: 5-13.

- Menendez ME, Ring D, Bateman BT (2015) Preoperative opioid misuse is associated with increased morbidity and mortality after elective orthopaedic surgery. Clin Ortho Rela Res 473: 2402-2412.

Corresponding Author

Dr. Maham Khalid, BMSc, Niagara Regional Campus, Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine, McMaster University, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, Tel: (647)-983-6096.

Copyright

© 2021 Khalid M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.