Transition from Military Health Care Provider to Nursing Student

Abstract

Aims

To describe the transition process from military health care provider to nursing student from the perspective of the student veteran and to discover the types of resources, assets and liabilities involved in the transition process to ensure the student veteran is successful in seeking a baccalaureate nursing degree.

Design

A grounded theory qualitative study was conducted using individual interviews.

Methods

Individual semi-structured interviews were held with 17 student veterans in an accelerated Veteran to Bachelor of Science in Nursing program between December 2016-December 2017. Strauss and Corbin's grounded theory approach was used for data analysis.

Results

From the analysis, four main themes emerged for the military: (a) Joining the military; (b) Active duty; (c) Medical training/experiences; and (d) Academic preparation. Four main themes emerged for nursing school: (a) Nursing program; (b) Didactic; (c) Campus services; and (d) Blending in. The most important attributes contributing to successful transition were prior military medical training and experience and strong social support resources and personal coping strategies.

Conclusion

The present study makes a novel contribution to understanding the importance of the perspective of student veterans in developing a guiding theoretical framework specific to student veterans.

Impact

Nursing faculty play a major role in facilitating the transition from the military to nursing school, and are being challenged to develop strategies to provide quality education that supports learning and prepares student veterans to enter the nursing workforce across the world. Although student veterans transitioning from the military to nursing school have begun to be studied, no studies to date have examined Transition Theory as a theoretical framework for how student veterans experience this transition. For the first time, the results of this research prove that a guiding framework on transition is a key aspect to the development of a theory specific to student veterans.

Keywords

Nursing, transition, grounded theory, student veteran, military healthcare provider, Veterans BSN program

Introduction

Globally, military health care providers may serve as a pipeline to address the world-wide nursing shortage. According to the World Health Organization [1], by 2030 an additional nine million nurses will be required to fulfill the shortage of nurses world-wide. Every year, approximately 200,000 men and women leave U.S. military service and return to life as civilians [2]. In the U.S. the RN workforce is expected to grow from 2.9 million in 2016 to 3.4 million in 2026, which is an increase of 438,100 or 15% [3].

Creating educational options for service members who are transitioning back into civilian life is a challenge for colleges and universities. This is particularly the case for military medics and corpsmen who desire to attend nursing school. These potential nursing students have been prepared by the United States Military to generally function autonomously while performing complex medical procedures with a focus on saving lives following catastrophic injuries. The role of nurses encompasses many distinct differences which maybe contrary to the assigned responsibilities of the military health care provider; a health care provider who has often been called "Doc" by those in their care [4,5]. The adjustment of student veterans who are transitioning from military health care provider to nursing student is difficult and, often, not well understood.

Background

During the last 5 years there has been a dramatic increase in the nursing literature regarding veterans transitioning into baccalaureate nursing education, in large part due to the implementation of Veteran to Bachelor of Science in Nursing (VBSN) programs throughout the United States. The focus has been on how to best accommodate the growing number of veterans seeking to earn bachelor's degrees in nursing [6-8]; while creating supportive, meaningful educational programs to meet the needs and to promote educational success for student veterans [9,10].

The literature supports the major roles that nursing faculty have in facilitating the transition from the military to nursing school, developing strategies to support learning, and preparing student veterans to enter the nursing workforce. Elliott, Chargualaf, and Patterson [11] examined the experiences of faculty who were teaching student veterans and how they could facilitate the transfer of knowledge from their military experience to their nursing program. The study results reported that "In order for nursing faculty to enhance the transfer of learning, they must first understand what veterans bring to nursing education and how their past experiences influence the teaching-learning process" (p. 626).

In addition, faculty can facilitate the transition of veterans by demonstrating cultural sensitivity and competence, understanding the shared meaning between their military experiences and nursing, appreciating diversity, and teaching them how to apply their prior knowledge and skills to current nursing practice [11]. It is paramount that faculty emphasize the multitude of strengths that student veterans have to achieve academic success, such as leadership, integrity, responsibility, teamwork, perseverance, global health awareness, and work ethic [12-14].

Veterans may struggle with significant personal and social stressors during their transition, such as the stigma of being a veteran, difficulty with peer relationships, and personal and financial responsibilities [13]. Adjustment to the differences in military and nursing education environments and culture is stressful [15-17]. Therefore, nursing faculty need to focus on minimizing the stressors and maximizing the strengths of the student veterans.

The Study

Aims

This study sought to develop a grounded theory to explain the experience of transition for student veterans attending an accelerated Veteran to Bachelor of Science in Nursing (VBSN) program.

Design

A qualitative, inductive grounded theory approach was chosen for the study using individual, semi-structured interviews with student veterans to guide the identification of key themes relying on their shared feelings and experiences and the development of a theory of veterans' transition experiences [18]. Insight from a study by DiRamio, Ackerman, and Mitchell [19] exploring the transition of student veterans from wartime service to the college provided guidance for data collection and analyses. The basic results of the DiRamio, et al. study can be applied to military health care providers transitioning to nursing student in an accelerated VBSN program.

Sample/participants

The research was conducted at six state-wide clinical nursing sites of a large university in a southwestern state. Purposive sampling was performed based on student veterans who were enrolled in the first and second classes of an accelerated VBSN program. Participants were recruited via research team members who were faculty in the program either in a face-to-face or a videoconference meeting, asking each potential study subject if they would like to participate in the research (Table 1 Participant Demographics). At this meeting, the study was explained, questions were encouraged and answered, written informed consent was obtained, and a copy of the signed consent was given to each participant.

Data collection

Individual semi-structured interviews were scheduled at the student veteran's clinical location. Since the study began during Cohort 2016's final semester, those participants were only interviewed once--during their last semester. Cohort 2017 participants were interviewed three times, once during each semester of the accelerated VBSN program. Each participant completed a demographic questionnaire before the first interview. The interviews were audio-recorded and conducted either face-to-face or via electronic video conferencing depending on the student veterans' clinical location. The interviews varied in length from 20-60 minutes and consisted of eight scripted questions asking them to describe their transition from the military to nursing student (Appendix A). Some of the questions for the second and third interviews were altered to accomplish this process in order to further explore the student veteran views based on the semester of the program. Participants openly discussed their feelings and perceptions regarding experiences while in the VBSN program. Data collection continued until saturation was achieved in order to fully develop patterns, concepts, categories, properties, and dimensions of transition. Once all 39 interviews were completed, the audio recordings were transcribed by an independent transcriptionist adhering to ethical principles of confidentiality of the data.

Analytical memos were used by the research team between coding and writing. Memos were completed immediately following the interview to allow for the emergence of developing patterns and connections among codes, categories, subcategories, and themes of each transcript. Memos assisted in the identification of relationships between categories and provided a written record of analysis related to the formulation of theory [20] and allowed the researchers to gain movement away from the data to abstract thinking and then return to the data to "ground" these abstractions into reality [21]. The research team communicated electronically following each interview, to build consensus on what the emerging categories were, how elements within the categories related to one another, any social processes that were discovered, and to resolve any disagreements between interpretations.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the University's IRB and participation was voluntary. Participants had the option to withdraw from the study at any time without impact on their grade or performance evaluation and were offered support resources if needed. Participants were compensated with a $5 gift card at the completion of each interview. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Audio recordings were destroyed post-transcription and transcriptions were stored on a password-protected computer in the primary investigator's office.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously by the researchers according to the steps described by Strauss and Corbin [22]. The data was broken down into conceptual components to begin to understand and "make sense" of the data. Emerging codes were constantly compared with existing codes to examine similarities and differences and similar codes were grouped together to form categories. Using the NVivo® 2012 [23] software, content analysis of the 39 interview transcripts was completed using patterned coding and line by line coding was done to identify concepts and key phrases, moved into subcategories, then categories. Theoretical sampling was used to refine the categories by producing more data to support or refute the categories that were initially identified. Specific experiences, events, and relationships mentioned by the participants were each coded into corresponding categories and categories synthesized into themes. The research team worked together to compile a final list of themes which provided clear definitions, an excellent reliability check for the coding strategy and assisted the audit trail. The final list of themes were used to identify the types of transition and the factors of the 4S System (Situation, Self, Support and Strategies).

Rigor

Rigor was achieved in this study through eight key steps articulated by Chiovitti and Piran [24]. The steps included:

1. Letting the student veterans guide the process,

2. Checking the theoretical constructs that emerged against the student veterans' meanings of the phenomenon of transition,

3. Using student veterans' actual words in the theory,

4. Identifying the researchers' personal views,

5. Specify the criteria built into the researchers' thinking,

6. Describing how and why student veterans were selected,

7. Discussing the scope of the study and,

8. Describing how the literature relates to each category that emerged in the theory. (p. 430)

Due to the geographical distribution of the students, four researchers were needed to complete the interviews across the state. They were trained in the grounded theory approach, conducted semi-structured interviews, and used memos to record their reflections and impressions. An audit trail was kept to document the conformability of the results. One of the researchers had expertise in grounded theory, was immersed in the data throughout all aspects of the study, especially the data collection and data analysis, and provided the oversight for the study. Student veterans' own words served as examples of the research processes of data analysis and theory development. Credibility was established with five student veteran study participants providing additional clarity and elaboration to the themes.

Theoretical framework

The aim of this grounded theory study was to develop a theoretical explanatory framework for the transition process of student veterans from military health care providers to nursing student. The research team did not use a theoretical framework or philosophy to guide the current study, but rather remained open in our awareness of the concepts of transition. Once the data analysis had been completed, the researchers compared the preliminary theoretical concepts and explanations to established theories and theoretical frameworks for similarities, differences, and consistency. The theoretical concepts and explanations identified from the study were validated from psychology related to adult development, adult transition, and human adaptation.

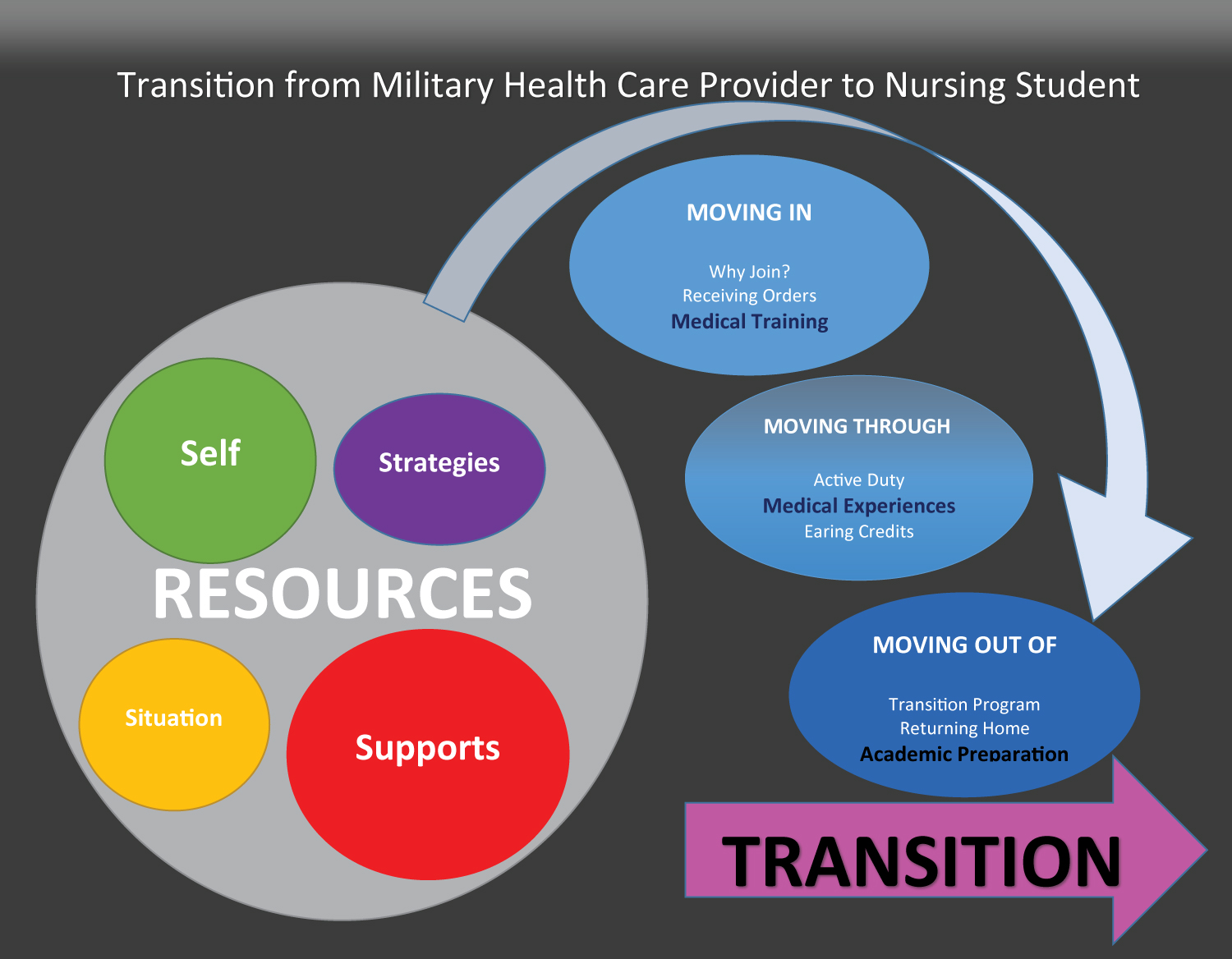

As was done by the DiRamio, et al. [19] study on student veterans, Schlossberg's Transition Theory [25], was explored in this study to determine the application to VBSN students. Transition Theory is considered a general theory of adult development that focuses on understanding how individuals make a transition and cope through life's various challenges. Coping is assessed by identifying the assets and liabilities an individual brings to a transition. According to Schlossberg, Waters and Goodman [26], transition is defined as "any event, or nonevent, that results in changed relationships, routines, assumptions, and roles" (p.27). The theoretical premises of this theory are that adults continuously experience transitions, adults' reactions to transitions depend on the type of transition, their perceptions of the transition, the context in which it occurs, and its impact on their lives. Transition Theory [26] identifies a process over time with no end point as adults move in, move through, and move out of transition.

Results

Nursing school transition

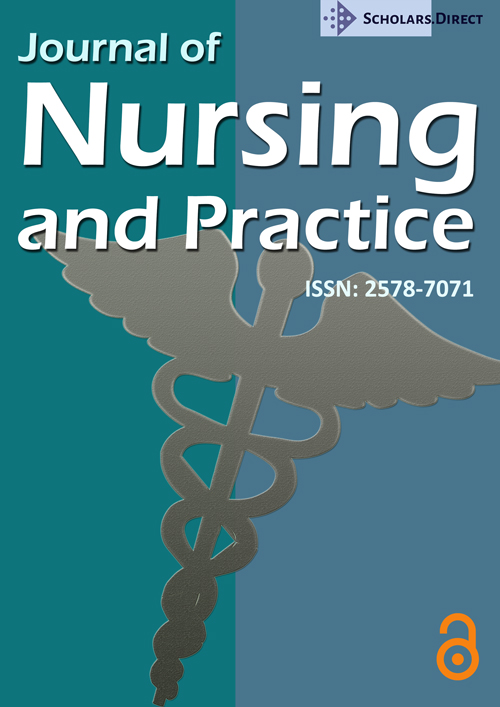

Through inductive analysis, transition emerged as the core category to describe student veterans' experiences of transition from military health care provider to nursing student. Two subcategories of transition were military health care provider and nursing school. Themes under military health care provider included: Reason why joined military, receiving orders, medical training, active duty, medical experiences, earning credits, transition program, returning home, and academic preparation. Themes under nursing school were: Program, blending in, finances, clinical, didactic, clinical competency assessments, campus services, veteran peers, and career services (Figure 1 Themes of Transition).

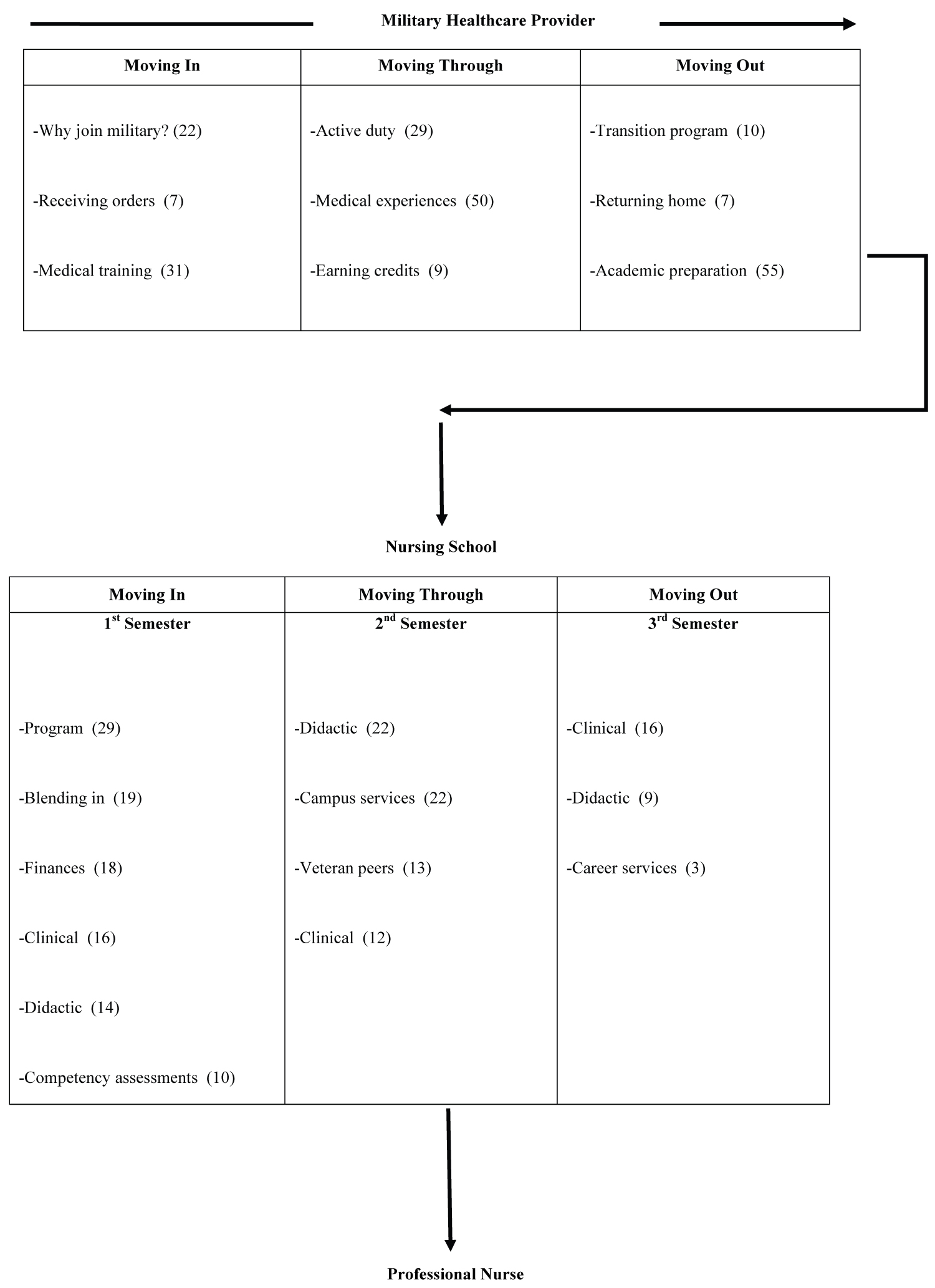

Transition types

In approaching a transition, it is important to identify the transition as it happens and determine if it is anticipated, unanticipated, or a nonevent. Anticipated transitions are events that are planned, scheduled, or expected over the course of a lifetime, such as marriage, graduation, or retirement. Unanticipated transitions are unexpected, unpredictable, or crisis events that are not normal, everyday occurrences, such as divorce, illness, or death. Nonevent transitions are events that are expected, but don't happen, such as promotion, marriage, or diagnosis [26]. All three types exist in the transition from military health care provider to nursing student (Figure 2 Nursing School Transition).

Transition process

The model for adult transition, "Moving In, Moving Through, Moving Out" [27], was useful to illustrate how the student veterans coped with transitions. The 18 themes identified in our study are organized within the model (Figure 1 Themes of Transition). As student veterans moved across the three phases, they evaluated each transition over the 3 semesters, decided the positive or negative effects in their lives, and utilized available resources (coping strategies, personal strengths and weaknesses, & social supports) to alter a situation, control the meaning of the transition and manage the stress [27]. Phase 1 (Moving In) began upon entering nursing school and ended at the end of the first semester. Phase 2 (Moving Through) involved the second semester, and Phase 3 (Moving Out) was the third semester in a one year accelerated VBSN program.

Coping

Individuals go through transitions in different ways. Often, when individuals are in the middle of one transition, they also have other transitions, which makes coping difficult for them. All individuals have assets, liabilities and resources that are used to influence the context of transitions. An individual's ability to cope effectively depends on their ability to balance assets and liabilities. Assets may outweigh liabilities making an individual's ability to cope with the adjustment easy; however, when liabilities outweigh assets the adjustment is difficult. Four major factors, identified as the '4S System', influencing an individual's ability to cope are Situation, Self, Support and Strategies [28]. These four factors are regarded as "potential assets and/or liabilities" (p. 61). The transition from military health care provider to nursing student revealed that the most important asset and resource were having a strong support system followed by self (personal psychological characteristics), with strategies (coping), and situation (circumstances) being equal (Figure 2 Nursing School Transition).

The 4S system

The 4S System provided a framework for identifying strategies to assist student veterans in their transition from the military to nursing school (Figure 3 4S System). Anderson, et al. [28] described this approach to help veterans "enhance their resources for coping by assessing their situation, self, support, and strategies" (p. 195).

Situation: What is happening and what are the stressors that are going on in a student veteran's life during this transition from the military to nursing.

Stressors reported by the student veterans in the study included requirements of the nursing program, blending in with peers, financial concerns, the difficulty of testing, fast pace and rigor of the nursing program, and managing commitments between school and ongoing military obligations as well as earning a living. The results are reinforced by DiRamio, et al. [19] who also found the transition to college was among the most difficult adjustments to be made when returning from the military. The value of conducting individual assessments prior to the start of classes enables faculty and staff to identify the resources that might be needed by individual students. Having a designated veteran's liaison to provide guidance and support during the application and admission process and to offer ongoing counseling following matriculation of student veterans is essential [29].

Veteran Asset: "I think the most interesting part is me transitioning to civilian life and remembering that they don't have the background that I have."

Veteran Liability: "I was afraid that my medical military experiences wouldn't transfer over to nursing school."

Self: Each student veteran has different life issues, personality, sense of meaning and resiliency.

Student veterans viewed themselves as being different than their peers. The military hierarchy carried over and student veterans expressed a reluctance to ask for help, to talk about their military experience, and struggled with the ambiguity of the academic environment. The student veterans observed the differences that arose from their level of maturity, stage of life, outlook, and values between themselves and their peers. Beginning in orientation and throughout the first two weeks of classes, the faculty need to inform the student veterans what the ‘Rules of Engagement' in academia are (i.e. nursing program rules and expectations, academic environment and culture, the role of faculty, etc.). Amore structured milieu within which student veterans can interact and feel comfortable helps them focus on learning. Providing more structure at the beginning of the nursing program and gradually increasing independent critical thinking and decision making is advantageous. By adapting the learning process to each student veteran's specific learning needs as well as their strengths and weaknesses, faculty can enhance their coping skills, promote a sense of control and define how their efforts will positively affect their learning outcomes.

Veteran Asset: "I think it really helped me develop a study sense and being able to kind of take learning in my own hands and in charge of my own learning process."

Veteran Liability: "One of the difficult transition points though from a military mindset in general but also as a medic in the military to trying to do something in the civilian world is how different the two worlds are."

Support: What help and social supports are available for each individual.

Social support was identified by student veterans as the major resource to help them cope with emotional burdens arising from the transition from the military to nursing school. Student veterans described the importance of the strong brotherhood of the military family, neighbors and friends who were veterans, veteran service organizations, and their intimate family unit. The student veterans in the study reported a variety of significant social support resources which they relied on consistently. It is important for schools to determine where there may be gaps in support, to provide information and/or referrals on local veteran support groups, the VA hospitals and clinics, student veteran services and associations, and to create a campus-based student veterans' network. A mentorship program with student veteran alumni can guide students, offer honest feedback, support the growth and development of the students, and serve as a source of wisdom.

Veteran Asset: "The military is something that is so unique in itself and intensive an experience that you develop such a close bond with these people and that bond will last a lifetime."

Veteran Liability: "I just kind of sat down and just cried because it's like I just don't know. You just hit those points sometimes where you hit that low or you hit that wall and it's just like is this some of my military issues flaring up as a result of or is it just purely just the stress?"

Strategies: How does an individual cope?

Coping involved the strategies that student veterans used to present, alleviate or respond to stressful events in their lives. Student veterans discussed various coping strategies which included communication with others, schedule planners to help with organization, self-reliance, adapting their prior military leadership styles, maintaining good mental health, study discipline, and seeking tutoring assistance. It is critical to identify and validate how student veterans cope with stress, since it is easier to build on existing successful coping strategies than to learn new strategies [28]. If existing strategies are ineffective, other options which might be considered include providing referrals for mental health counseling, maintaining open channels of communication, encouraging the development of study groups, creating an online student veterans' forum, establishing a military liaison on each campus, and coordinating a veteran speaker to meet with student veterans on an ongoing basis.

Veteran Asset: "Most important things always is communication."

Veteran Liability: "There's a lot of people that get in & out [of the military], so it's almost like an assembly line of things you have to do, just check the box."

Discussion

The main results of this study portrayed the challenging journey of student veterans transitioning from military health care provider to nursing student. This is consistent with the recent literature which shows that during transition from the military to an academic nursing program, student veterans encounter many difficulties and personal challenges [12], including adjustment to civilian and academic cultures [13], resulting in stress and increased suicide risk [8,30]. The student veterans in this study identified the transition to the nursing school as one of the most difficult adjustments to be made when returning from the military. Social support was the main resource to help them cope with transition and must be fostered in nursing programs.

Had the transition process changed for student veterans over the last decade?

Over the last decade, the transition from the military to a college setting can still be a difficult process for student veterans, but the majority are able to cope successfully with the various challenges along the way. "Blending in" with fellow classmates, connecting with peers, and financial concerns continued to be major aspects of the adjustment process for the student veterans [19]. Through the use of strong social support resources and personal coping strategies, student veterans transitioning to nursing student have managed the stress of transition without being overwhelmed by it. Furthermore, this study validates previous research recognizing positive experiences, qualities, and strengths that student veterans bring to nursing education: character, honor, strong work ethic, self-discipline, goal-focused, leadership skills, critical thinking, decision making, maturity, sense of purpose, integrity, responsibility, teamwork, disciplined, driven, perseverance, global perspective, and increased self-efficacy [12-14,29].

Had Schlossberg's Transition Theory (1984) been generalizable to different types of transition experiences for student veterans in nursing programs?

Our results indicated that Transition Theory (1984) is relevant to student veterans moving from military health care provider to nursing student. Overall, their vast military and medical training and experiences proved to be an enormous asset in their transition process from military life to campus life [19]. During nursing school, there were three unanticipated transitions that impacted their coping abilities the most: Changing their way of thinking, the fast pace and rigor of the program, and the complexity of the clinical competency assessments. Even though research has been documented on Schlossberg's Transition Theory to study student veterans who transition into higher education [31,32]; to date, no research has used this theory to study student veterans transitioning from the military into nursing school.

Had this study extended the research on student veteran transition from military health care provider to nursing student?

As a result of our study, we discovered we could extend the Transition Theory [25], as used in the previous study on student veterans transitioning to a college setting [19], by providing insight and understanding for student veterans transitioning from military health care provider to the role of nursing student. We expanded on old theoretical concepts and developed new ones. Since it is the accumulation of knowledge over time that is important, future refinement and validation of theoretical concepts and explanations will contribute to the development of a theory of transition specific for student veterans.

Limitations

Several limitations require consideration. A major limitation noted in this study was the small sample size from multiple geographical locations. Other limitations included unequal representation from the different branches of the military, varying military medical backgrounds and experiences, the amount of time from the actual military separation to nursing school, and several different faculty conducting interviews.

Conclusion

The data revealed the challenging journey of student veterans as they transitioned from a military health care provider to nursing student. These veterans had to adjust not only to the return to civilian life; but also to the culture of an academic environment. Implications for nursing education include: developing a better understanding of the challenges of student veterans coping with adjustment in an academic environment, creating relevant learning experiences based on their military knowledge and experience, using teaching strategies that support their individual learning needs and styles, and assisting student veterans in connecting with their own strengths and weaknesses, coping skills, and resources they need to achieve a successful journey.

Recommendations for further work include studying the transition from nursing school to professional nurse by evaluating how they have been adjusting to their new roles as registered nurses, determining the generalizability of Schlossberg's Transition Theory [25] to different types of transition experiences as student veterans transition into graduate nursing programs, and refining and validating theoretical concepts and explanations which will contribute to the development of a transition theory specific for student veterans.

References

- World Health Organization. (2018) Nursing and midwifery. Fact sheets: Detail.

- S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2018) The military to civilian transition 2018: A review of historical, current, and future trends.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN] (2020) Nursing shortage: Current and projected shortage indicators. Washington, D.C. USA.

- Kirkpatrick T (2017) 5 key differences between Army medics and Navy corpsmen. We Are The Mighty.

- Smith S (2020) Combat medics in the different military branches. The Balance Careers.

- Champlin B, Linck R, Darst E, et al. (2017) Veteran-centered exemplars in a prelicensure nursing program curriculum. Nurse Educ 42: 255-258.

- Hurlbut J, Revuelto I (2018) Transitioning veterans into a BSN pathway: Building the program from the ground up to promote diversity and inclusion. Med Surg Nurs 27: 266-269.

- Voelpel P, Escallier L, Fullerton J, et al. (2018) Transitioning veterans to nursing careers: A model program. J Prof Nurs 34: 273-279.

- Carlson J (2016) Baccalaureate nursing faculty competencies and teaching strategies to enhance the care of the veteran population: Perspectives of veteran affairs nursing academy (VANA) faculty. J Prof Nurs 32: 314-323.

- Gibbs C, Lee C, Ghanbari H (2019) Promoting faculty education on needs and resources for military-active and veteran students. J Nurs Educ 58: 347-353.

- Elliott B, Chargualaf K, Patterson B (2019) Committing to my mission: Faculty experiences with student veterans in baccalaureate nursing education. Nurs Forum 54: 619-628.

- Chargualaf K, Elliott B, Patterson B (2018) From military to academic nursing: Embracing an untapped leadership resource. J Nurs Educ 57: 355-358.

- Dyar K (2016) Veterans in transition: Implications for nurse educators. Nurs Forum 51: 173-179.

- Patterson B, Elliott B, Chargualaf K (2019) Understanding learning transfer of veterans in baccalaureate nursing programs: Their experience as student nurses. Nurse Education in Practice 39: 124-129.

- Gregg BT, Howell DM, Shordike A (2016) Experiences of veterans transitioning to postsecondary education. Am J OccupTher 70.

- Kato L, Jinkerson JD, Holland SC, et al. (2016) From combat zones to the classroom: Transitional adjustment in OEF/OIF student veterans. Qual Rep 21: 2131-2147.

- Patterson B, Elliott B, Chargualaf K (2019) Discovering a new purpose: Veterans' transition to nursing education. Nurs Educ Perspect 40: 352-354.

- Glaser B, Strauss A (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for quantitative research. Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, IL, USA.

- DiRamio D, Ackerman R, Mitchell R (2008) From combat to campus: Voices of student-veterans. J Women High Educ 45: 73-102.

- Corbin J, Strauss A (1990) Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol 13: 1-19.

- Strauss A, Corbin J (1994) Grounded theory methodology. In: N Denzin, Y Lincoln, Handbook of qualitative research. (5th edn), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 273-285.

- Strauss A, Corbin J (1998) Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. (3rd edn), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

- NVivo® (2012) Discover NVivo®. QSR International.

- Chiovitti R, Piran N (2003) Rigour and grounded theory research. J AdvNurs 44: 427-435.

- Schlossberg NK (1984) Counseling adults in transition: Linking practice with theory. (1st edn), Springer, New York, USA.

- Schlossberg NK, Waters EB, Goodman J (1995) Counselingadults in transition: Linking practice with theory. (2nd edn), Springer, New York, USA.

- Schlossberg NK, Lynch AQ, Chickering AW (1989) Improving higher education environments for adults. (1st edn), Jossey-Bass ,San Francisco, CA, USA.

- Anderson M, Goodman J, Schlossberg N (2012) Counseling adults in transition: Linking Schlossberg's theory with practice in a diverse world. (4th edn), Springer Publishing Company LLC, New York, USA.

- Morrison-Beedy D, Rossiter A (2018) Next set of orders: Best practices for academia to ensure student success and military/veteran focus. Nurs Educ Today 66: 175-178.

- Pease JL, Billera M, Gerard G (2016) Military culture and the transition to civilian life: Suicide risk and other considerations. Soc Work 61: 83-86.

- Bartee R, Dooley L (2019) African American veterans career transition using the Transition Goals, Plans, Success (GPS) Program as a model for success. J Veterans Studies 5: 1-13.

- Griffin K, Gilbert C (2015) Better transitions for troops: An application of Schlossberg's transition framework to analyses of barriers and institutional support structures for student veterans. J Higher Educ 86: 71-97.

Corresponding Authors

Dr. Jana C Saunders, School of Nursing, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, 3601 4th Street, Lubbock, Texas 79430, USA

Copyright

© 2020 Saunders JC, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.