Socio-Economic Household Surveys on the Application of Basic Preventive Measures Dictated by the WHO to Stop the Spread of COVID-19 in the Northern Zone of Cameroon

Abstract

Currently, the emergence of a new human coronavirus, COVID-19, is of concern to all humanity. In order to understand the effect of this disease on the behavior of populations, we conducted surveys of 900 households in 300 households per Region (Adamawa, North, and Far North) in Northern of Cameroon. The surveys focused on compliance with the basic preventive measures dictated by the WHO, the means developed by households to block the way to this COVID-19, and the activities that occupy them during the period of confinement. Among the measures proposed by WHO, households are more likely to frequently clean their hands with a hydro-alcoholic product or with soap and water, cover their nose and mouth with a handkerchief or the hollow of the elbow when coughing or sneezing, avoid touching their face, keep at least 1 meter away from others and are most confined in the Adamawa region. In the context where no specific therapy is available at the moment, households equip their medicine boxes with chloroquine phosphate. They also include more spices in their menus. The habits of the population have not remained on the fringes: Television, internet followed by reading and finally sports have taken a major place in the daily occupation. As hospitals in developing countries remain less equipped, limiting the spread of COVID-19 is crucial. Nowadays, COVID-19 constitutes a harmful pandemic, hence the informative value of this study for new decision-making by the authorities.

Keywords

Socio-economic surveys, COVID-19, Households, Septentrion, Cameroon

Introduction

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) is now a highly feared pandemic that is increasingly affecting countries across continents and races. COVID-19 is characterized by mild symptoms including runny nose, sore throat, cough, and fever [1]. COVID-19 is the third highly pathogenic human coronavirus to emerge in the last two decades [2]. The disease may be more severe in some individuals and may result in pneumonia or breathing difficulties. More rarely, the disease can be fatal in young people. Its mode of transmission directly or by self-inoculation of mucous membranes of the nose, eyes or mouth [3,4] makes it a serious health problem and a pathology feared by both governments and communities because of its impact on socio-economic and cultural life. The elderly, and people with other medical conditions (asthma, diabetes, or heart disease), may be more vulnerable and become seriously ill [5]. Affected people may experience the following symptoms: Runny nose, sore throat, cough, fever, severe breathing difficulties [1]. In order to prevent these scourges from causing shortfalls, WHO has put in place some preventive measures such as regular hand washing, coughing into the elbows, avoiding touching the face, keeping at least 1 meter away from others and confining them. At this stage when the level of cases is increasing day by day, what is the level of application of these measures and the measures developed by the populations of the Great North of Cameroon (Adamawa, North and Far North)? The answer to this question is the focus of future decisions. Thus represents a guide for action to the authorities.

Materials and Methods

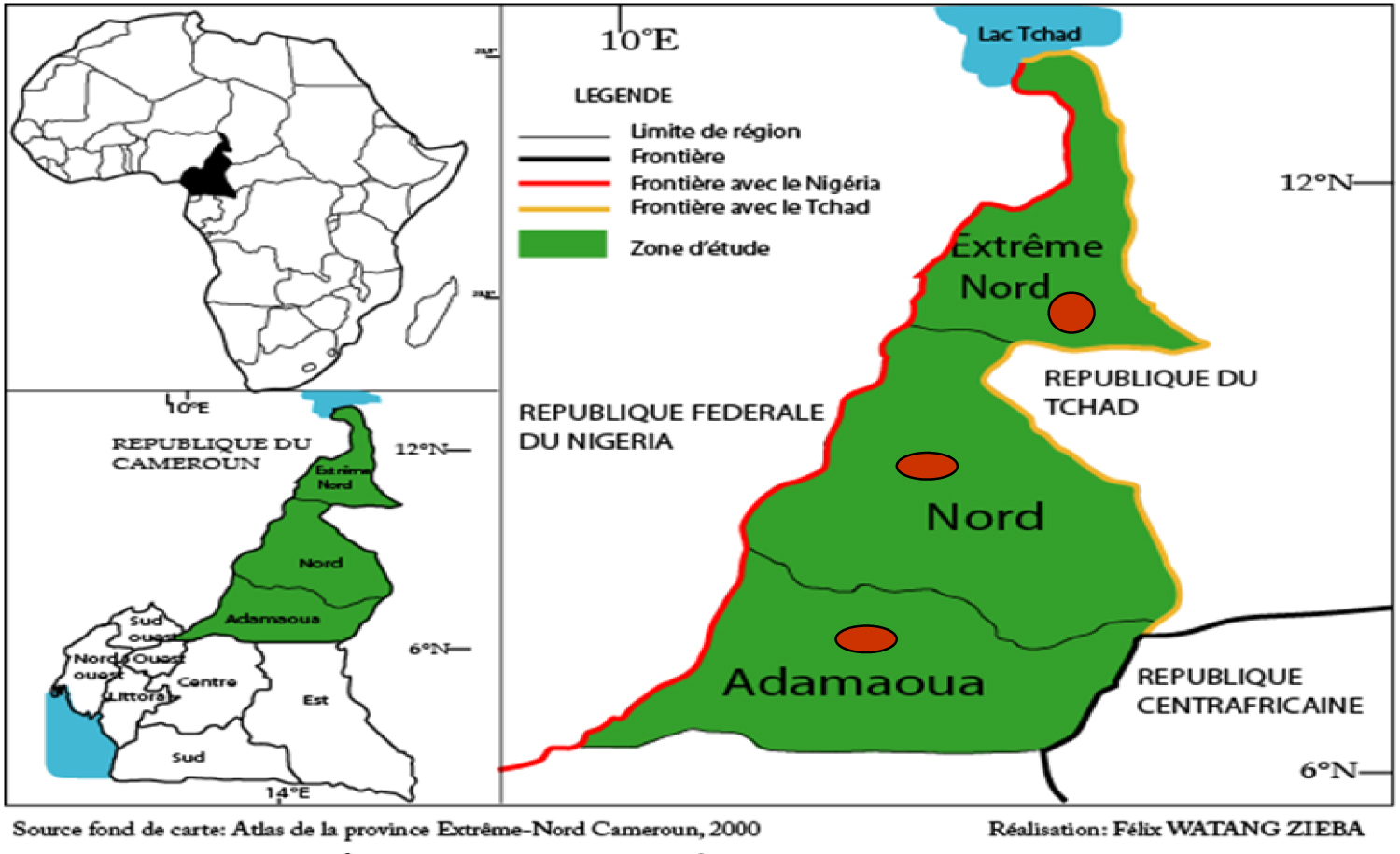

Study area

The study took place in the far north of Cameroon (Figure 1). The data collection period took place from 18 to 28 March 2020 in households in three (03) districts of the capitals of the Far North (Maroua), North (Garoua) and Adamawa (Ngaoundere) Regions.

Sampling and selection of informants

The quantitative household survey is the main source of data for this study. This survey was conducted on 900 households spread over 300 households per Region. Households were selected according to their proximity to transport agencies, markets and airports. These households thus represent the focal points of contact with the holy bearers propagating COVID-19 in the cities. The information sought from this survey was based on hygienic, therapeutic-preventive and social behavior.

Data analysis

Two main data analysis and exploitation grids allow us to highlight the results of the changes induced in the population in a state of psychosis. These data were transferred to the Statgraphicsplus 5.0 and Xlstat software for the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and correlation tests after the percentage calculation on the sphinx software. Duncan's test was applied to judge the difference between the means of the different treatments.

Results

Preventive measures against COVID-19

The prevention measures dictated by the WHO are applied in significantly different percentages (p ˂ 0.05) in the three Regions of the far North of Cameroon. Frequent hand washing with soap and water (75.0 ± 3.0%), covering the nose and mouth with a handkerchief or the hollow of the elbow when coughing or sneezing (42.0 ± 3.0%), avoiding touching the face with the hands (93.33 ± 5.51%), putting on a mask when you are away from home (12.66 ± 5.68%), keep the distance of at least 1 meter from the others (91.33 ± 1.53%), best maintain the distance of at least 1 meter (91.33 ± 1.53%) and containment (37 ± 1.47%) are best respected in the Adamawa Region compared to the Northern and Far North Region. However, the Far North Region practices more frequent hand washing with a hydro-alcoholic (54.66 ± 13.05%) compared to the Adamawa Region (43.0 ± 10.54%) and the North (34.0 ± 8.19%) (Figure 2).

Therapeutic-preventive means of COVID-19

Table 1 presents the measures developed by populations faced with the emergence of COVID-19. From this table, it emerges that the populations of the Far North remain in search and endow their medicine boxes in a non-significant way (p ˃ 0.05) with chloroquine phosphate, 72.0 ± 14.42% (North), 69.0 ± 5.59% in the Far North Region and 66.33 ± 10.01% (Adamawa). To this should be added the inclusion of spices 86.67 ± 4.73% (Adamawa); 69.67 ± 5.03% (Far North) and 66.67 ± 5.03% (North) with a significantly different difference (p ˂ 0.05) in the menus.

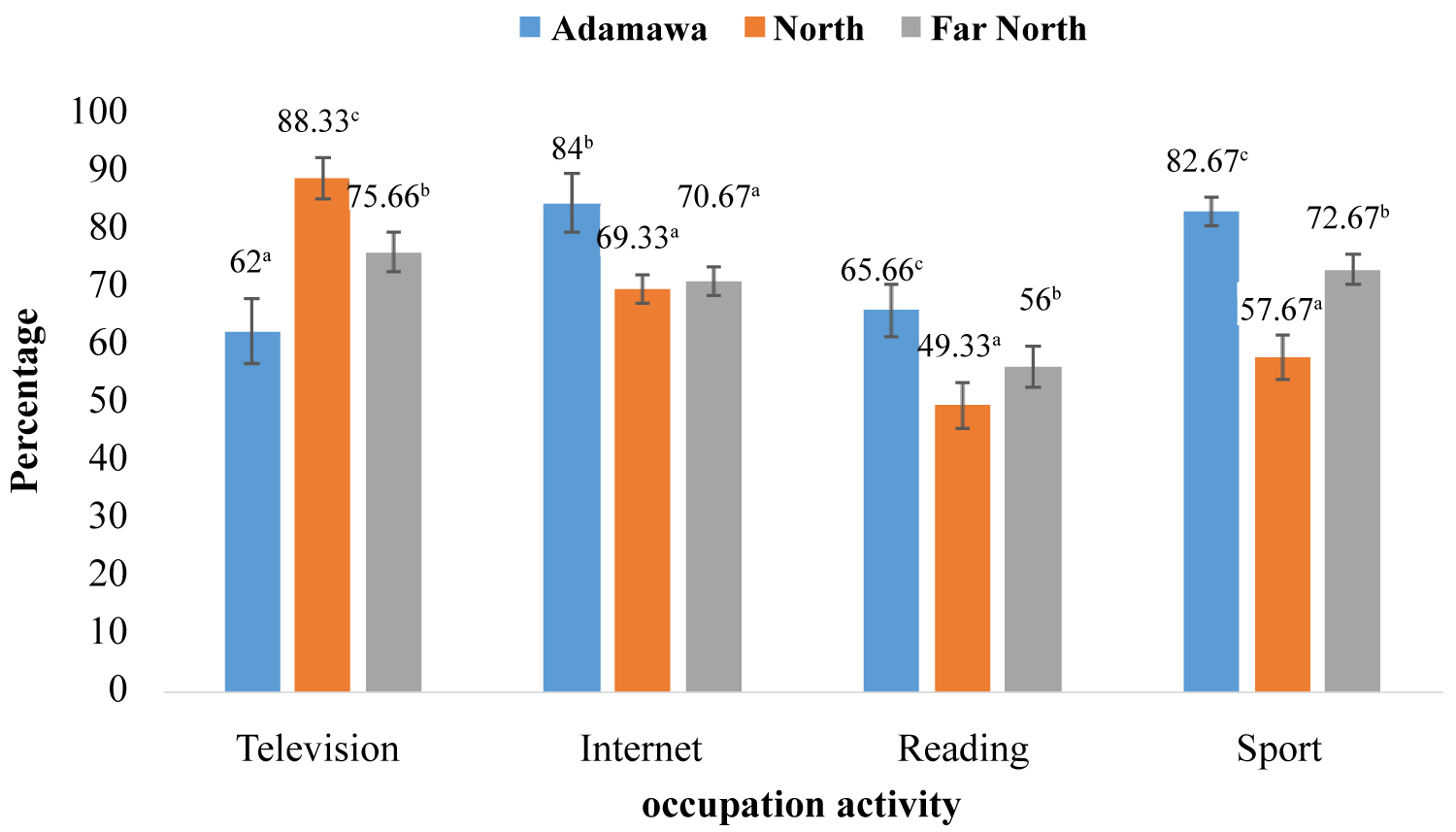

Occupation

Populations in the Far north Cameron adopted habits that differed significantly (p > 0.05) from one Region to another to reduce the stress of psychosis from the daily confinement inedited (Figure 3). Figure 3 shows that interest (84.0 ± 5.0%) and sport (82.67 ± 2.51%) are the major occupations of the populations of Adamawa region. While in the North region, television (88.33 ± 3.51%) followed by the internet (69.33 ± 2.52%) captivate households the most. Moreover, in the Far North Region, the population preferentially spends time in front of the television (75.66 ± 3.51%) and practices sports (72.67 ± 2.64%). However, the least popular activity is reading 65.66 ± 4.50% (Adamawa), 56.0 ± 3.52% (Far North) and 49.33 ± 4.04% (North).

Discussion

Human coronavirus can remain infectious when inanimate surfaces at room temperature for up to 9 days. At a temperature of 30 ℃ or higher, the duration of persistence is shorter [6]. As a result, populations in the far north of Cameroon are not immune to COVID-19 despite the high temperatures. Hence the need to carefully apply the preventive measures recommended by the WHO. Containment as a barrier measure (≤ 37.0 ± 1.53%) is weakly applied in the Great North Cameroon. Indeed, Cameroon, like most African countries, does not provide a strict minimum of income to the majority of the poorest population. As a result, people are forced to choose between staying at home and dying or leaving and exposing themselves to possible contamination. Faced with an uncertain future, heads of families leave their homes for their livelihood, which is an obstacle to the eradication of COVID-19. Frequent washing of hands with soap and water (75.0 ± 3.0%) is more prevalent in the Adamawa Region than in the North Region (64 ± 8.19%) and the Far North Region (39 ± 13.05%), which can be explained by the problem of access to water, which is all the more difficult in the North and Far North of Cameroon. Indeed, in the Far North Region, access to water is a crucial problem that requires a great deal of effort [7]. As a result, water is used in cases of extreme necessity in the dry areas of northern Cameroon. Yet hand washing with soap and water is very important both to avoid self-inoculation and contamination of relatives [8,9]. Covering the nose and mouth with a handkerchief or covering the hollow of the elbow when coughing or sneezing is less respected (˃ 50%) as this was not really part of daily habits. In addition, avoiding touching the face with the hands (˂ 90) is an ancestral practice and therefore easy to respect as a preventive measure at COVID-19. This does not corroborate the work of [10] where students touch their faces with their own hands an average of 23 times per hour. The very low wearing of masks during out-of-home periods (≤ 12.66 ± 5.68%) and frequent hand washing with hydro-alcoholic gel (≤ 54.66 ± 13.05%) is not within WHO expectations [11]. This could be mainly due to the shortage caused by border closures and reduced activity in manufacturing plants. In addition to the poverty and food insecurity in this part of Cameroon. In a context where having an economy to ensure a balanced and sufficient food ration is difficult it remains complicated or even impossible to buy a mask or gel. Maintaining a distance of at least 1 meter from others (≥ 91.33 ± 1.53%) is better applied because long before the populations of the Far North Cameroon claim to have always maintained this habit as it is perceived as a sign of respect. Moreover, the low respect of confinement (≤ 37 ± 1.47%) is the result of a failing socio-economic and educational system with low impact. Indeed, most of the inhabitants of the Far North of Cameroon survive activities (trade, livestock, agriculture and fishing) that require actors to leave their homes almost every day. Moreover, educated young people do not consistently apply what they are taught in educational institutions. However, transmission can be successfully prevented when appropriate measures are carried out regularly [12,13]. The medical measures developed by the populations of the Far north of Cameroon in the face of the emergence of COVID-19. Although chloroquine phosphate is banned because of its acute intoxication [14,15], the populations of the far North of Cameroon are increasing the search for and use of chloroquine phosphate (≤ 72.0 ± 14.42%). This increase in chloroquine phosphate could be explained by the increase in the flow of media information [16,17] on the potential efficacy of this molecule on the coronavirus and the strong dominance of self-medication [18]. In addition, there is a high incidence of the integration of spices in menus (≤ 86.67 ± 4.73%). This would be due to the anti-influenza active ingredients that continent spices. The populations of the far north Cameron have adopted habits to reduce the stress of daily newspaper psychosis that were unheard of in this period of emergence of COVID-19. The daily household occupation during this pandemic period is television (≤ 88.33 ± 3.51%) followed by interest (≤ 84.0 ± 5.0%), sports (≤ 82.67 ± 2.51%) and reading (≤ 65.66 ± 4.50%). Television occupies a large place thanks to the multitude of programs it offers through the variability of the channels. The interest comes in second position due to the fact that it is interactive and gives access to numerous social networks (WhatsApp, Facebook...). The Internet also provides operators with the option of teleworking and teleconferencing. In spite of the fake news of the ill-intentioned users whose use it conveys, it has not waned because it is a channel that leads to the users' imaginations. The sport of share these benefits is well practiced in the far north of Cameroon at this time of confinement. Indeed, sport allows the liberation of the mind strengthens the body and is a means of escape from boredom. Faced with the emergence of COVID-19, reading is very weakly applied. This low percentage compared to other activities could be explained by the high illiteracy rate in the far north of Cameroon and the scarcity of libraries. In fact, households with a family library have a high rate of illiteracy and access to recent books remains difficult [19]. It should also be added that the interest in reading and books is not better understood by many people in this part of the country.

Conclusions

The effects of COVID-19 on habits are considerable and could undermine the progress made on the WHO front over the past decade, particularly in the areas of poverty reduction, food security, education and health. The sharp drop in essential occupations is a source of discontent that could further reverse the progress made in peace-building, national capacity building and nationwide stabilization in Cameroon. The seriousness of the situation requires urgent action to halt the epidemic and respond to the huge toll it is taking on communities and individuals, particularly in terms of loss of income, livelihoods and employment. Livelihood regeneration, income support and social protection programs need to be institutionalized in confined communities. It is incumbent on the governments concerned to identify the direct and indirect channels through which affects household incomes (including through stigmatization) and to institute proactive outreach programs to educate and reorient communities and investors on all these issues. This needs to be complemented by capacity building to treat those affected, provide essential services and further prevent the spread of coronavirus 2019 to new areas.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank all the referred whose contributions have been very significant for the improvement of this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

References

- De Wit E, van Doremalen N, Falzarano D, et al. (2016) SARS and MERS: Recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 14: 523-534.

- Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. (2020) A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet 395: 514-523.

- Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, et al. (2016) Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: The possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect 92: 235-250.

- Dowell SF, Simmerman JM, Erdman DD, et al. (2004) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus on hospital surfaces. Clin Infect Dis 39: 652-657.

- WHO (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation report-23.

- Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, et al. (2020) Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect 104: 246-251.

- Wakponou A (2016) L'eau, facteur de vie ou de mort? Experience de la ville de Maroua dans l'Extreme-Nord Cameroun. SYLLABUS Revue scientifique interdisciplinaire de l'Ecole Normale Supérieure. Série Lettres et Sciences Humaines 7: 216.

- Alshammari M, Reynolds KA, Verhougstraete M, et al. (2018) Comparison of perceived and observed hand hygiene compliance in healthcare workers in MERS-CoV endemic regions. Healthcare (Basel) 6: 4.

- Wong TW, Tam WW (2005) Handwashing practice and the use of personal protective equipment among medical students after the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. Am J Infect Control 33: 580-586.

- Kwok YL, Gralton J, McLaws ML (2015) Face touching: A frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control 43: 112-114.

- Siddharta A, Pfaender S, Vielle NJ, et al. (2017) Virucidal activity of World Health Organization-recommended formulations against enveloped viruses, including Zika, Ebola, and emerging Coronaviruses. J Infect Dis 215: 902-906.

- Wiboonchutikul S, Manosuthi W, Likanonsakul S, et al. (2016) Lack of transmission among healthcare workers in contact with a case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in Thailand. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 5: 21.

- Ki HK, Han SK, Son JS, et al. (2019) Risk of transmission via medical employees and importance of routine infection-prevention policy in a nosocomial outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): A descriptive analysis from a tertiary care hospital in South Korea. BMC Pulm Med 19: 190.

- Servonnet A, Delacour H, Thefenne H, et al. (2005) Acute chloroquine poisoning: Clinical and analytical aspects. Ann Toxicol Anal 17: 87-94.

- Musshoff F, Madea B (2002) Demonstration of a chloroquine fatality after 10-month earth-grave. Forensic Sci Int 125: 201-204.

- Baxerres C (2013) From informal medicine to liberalized medicine: An anthropology of pharmaceutical medicine in Benin. Paris: Contemporary Archives, 317.

- Ntsama Essomba C, Tiwoda C, Essomba Y, et al. (2011) Identification des questions de recherche prioritaires en matière de politique d'accès et d'usage des médicaments dans des pays francophones d'Afrique Centrale, a revenus faibles ou intermediaries, 7-70.

- Pouhè Nkoma P (2015) Itinéraires thérapeutiques des malades au Cameroun: Les déterminants du recours a l'automédication. Rapport MINEPAT-Division des Analyses Démographiques et des Migrations, 1-79.

- Benedith AO (2009) La mondialisation et les bibliothèques en Afrique: Les problèmes de s'auto-decouvrir dans le monde numérique. Congrès mondiale des bibliothèques et de l'information, 1-14.

Corresponding Author

Ali Ahmed Davy, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, University of Ngaoundere; Department of Biological Science, Faculty of Sciences, University of Maroua; Ecole Nationale Supérieur Polytechnique de Maroua, University of Maroua, Cameroon, Tel: (+237)-679-578-764.

Copyright

© 2020 Davy AA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.