Mental Health Issues Related to Some COVID-19 Aspects: Online-Based Bulgarian Survey

Abstract

The mental health of the population is affected during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The goal of our cross-sectional research was to explore some of the mental health dimensions and the attitudes of Bulgarian people during the pandemic through a direct online anonymous individual survey.

Materials and methods

The survey consisted of 24 questions and obtained responses from 1020 Bulgarian people.

Results

Our participants were in the predominant age group of 21-40 years (71.4%), mainly women, and 27.8% of all respondents were medical professionals. About one-third of respondents correlated COVID-19 with some malaise, and 29.8% were fearful of infecting themselves or their family members and friends. Nearly half of the participants were worried about the lack of specific treatment.

Conclusion

Our results and published data on previous epidemics and pandemics have shown that affected populations respond by affecting mental health and exhibit worrying symptoms.

Keywords

COVID-19, Mental Health, Pandemic, Coronavirus

Introduction

The complex term "mental health and psychosocial support" was introduced by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) specifically for crises, such as the current situation with COVID-19. The global definition of the term includes "any local or external support that aims to protect or promote psychosocial well-being and/or to prevent or treat mental illness" [1]. It is known that critical aspects of human mental health are affected during such trials [2].

Experience with previous epidemics caused by viruses from the coronavirus family shows that in addition to the social and economic damage to the affected countries, the psychopathological effects resulting from them are also a serious aspect of the crisis [2]. Not surprisingly, people working in medicine, including those on the front-line, are the most endangered contingent.

The MERS epidemic in 2012 also reported deterioration in the health of medical professionals during the epidemic [3,4]. Sometimes the disproportionate media dissemination of information about an epidemic can lead to adverse psychological and social reactions, as observed in previous epidemics with SARS, MERS, Ebola [5,6]. It should not be forgotten that the high mortality and virtually no asymptomatic contagion has limited the spread of these epidemics, which has limited severe psychological trauma only in the affected areas, sparing the world's population.

First of all, to choose the most appropriate approach to support mental health in a pandemic, it is essential to assess the mental state of the population. Our study aimed to examine some of the aspects related to mental health and perceptions of Bulgarian citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic through an anonymous direct survey conducted online.

Materials and Methods

For the cross-sectional study, a direct individual anonymous survey was created, containing 24 questions. The object of the study was Bulgarian citizens who received access to the survey online - through social media (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, etc.) and email. The design of the survey was such that it does not allow submission if the questions are not filled in as required. Primary empirical sociological information was collected through a questionnaire, prepared according to foreign questionnaires, and adapted to the existing conditions in our country. Responses were collected from 1020 Bulgarian citizens, and the individual empirical information was collected for ten calendar days in May 2020.

We used Software package for statistical analysis (SPSS®), IBM 2009, version 19 (2010), and Excel (v. 2010) for statistical processing of raw data. Statistical analysis of the raw data was performed by descriptive analysis.

Results

Demographic and economic characteristics of the participants

Out of all 1020 participants, women were predominant (n = 855, 83.8%). There were 156 men (15.3%), 5 people (0.5%) and 4 (0.4%) chose not to share their gender. In the age range 3.3% were under 20, 71.4% - between 21 and 40, 23.7% - between 41 and 60 and 1.6% - over 61.

Of all participants, 27.8% shared that their profession is related to medicine, including they are working on the front-line with patients with probable or proven COVID-19.

Answers to questions related to the health aspects of COVID-19

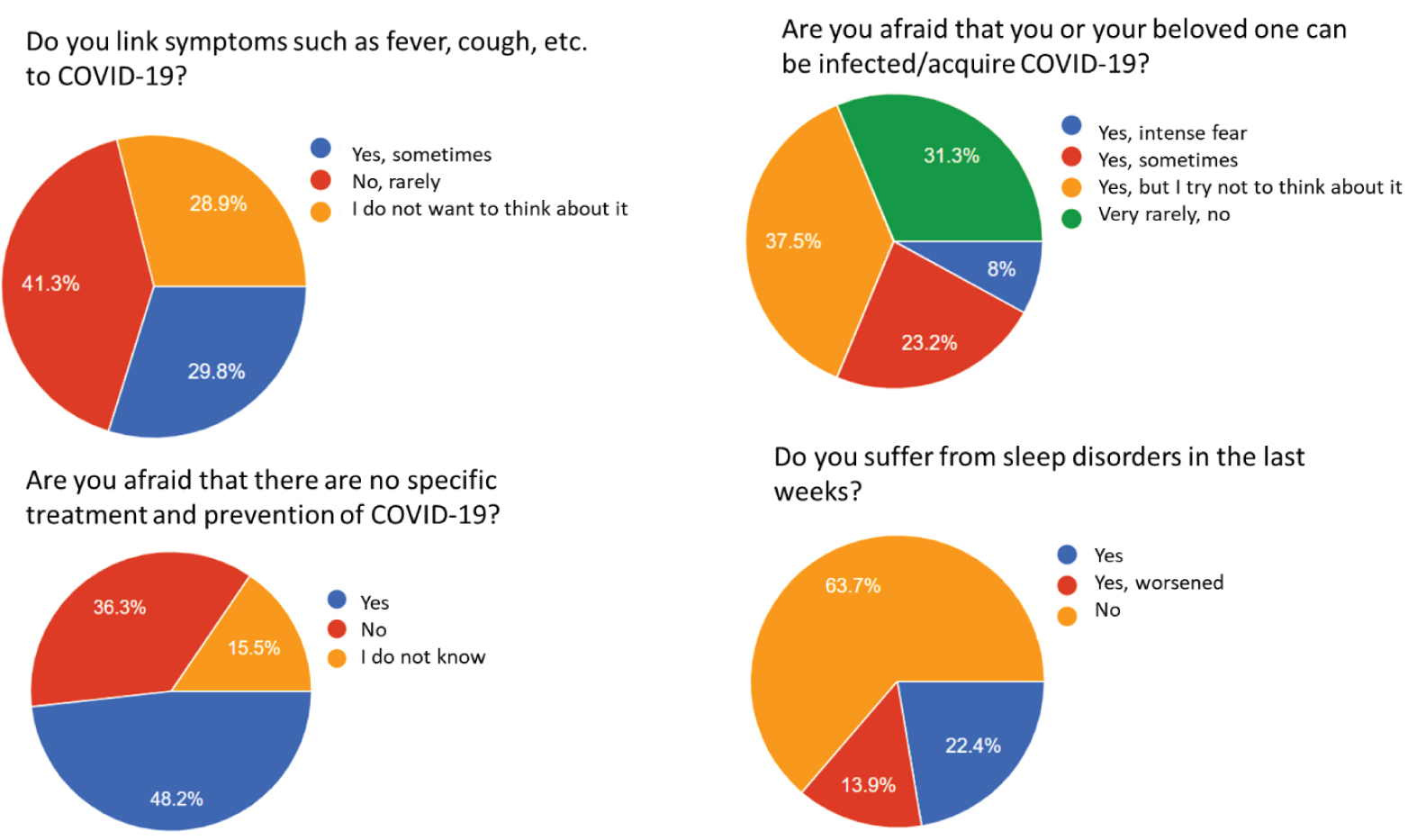

When asked whether respondents associated COVID-19 with the feeling of unwell and symptoms such as fever, cough, and others that may be related to the infection, the response rates were almost equally distributed as follows: 29.8% answered yes, 41.3% - with "no, rarely," and 28.9% - that they try not to think about it (Figure 1).

Regarding whether they feel an intense fear that they or some of their relatives may get sick, approximately one third (31.3%) answered with "very rarely, never." The remaining 69.7% admitted that they experienced such fear as follows - 8% - extreme fear, 31.3% - sometimes, and 37.5%, although experiencing such fear, tend not to think about it.

To the question "Are you afraid that there is no specific treatment and prevention?", Nearly half of the participants answered in the affirmative and 36.4% in the negative. 15.5% of the respondents could not judge their answers (Figure 1).

The majority of respondents (75.7%) did not want to get sick to "pass faster," 20.4% - said they thought so, but were not sure, and 3.9% answered "yes" to the question.

22.4% reported sleep disorders, 13.9% believed that they had a worsening of pre-pandemic sleep problems, and 63.7% did not report such conditions (Figure 1).

Discussion

Mental health and psychosocial responses to COVID-19 have changed since the WHO declared the crisis as a pandemic on March 11, 2020. It is common for people to feel stressed and anxious during any epidemic.

Frequent reactions of people directly and indirectly affected included fear of illness and death - for themselves and their loved ones (one-third of our respondents experienced intense fear); fear of losing a livelihood, inability to perform work duties during isolation, fear of being fired or not being able to find a new job.

The population was under stress due to the indirect effects of social isolation, quarantine, and restriction of citizens' freedoms. For our respondents, we observed the same trends for some specific stressful events accompanying the COVID-19 pandemic, such as symptoms of other diseases (especially respiratory) to be misinterpreted as symptoms of COVID-19 (almost one-third of respondents admit to such a tendency). When asked if they associated with COVID-19 symptoms such as fever, cough, and others related to the infection, the response rates one in three responded positively.

One of the most stressful aspects of the pandemic was the lack of specific treatment and prevention, which led nearly half of the participants to answer in the affirmative that it scared them. The majority of respondents did not want to get sick to "to end the fear," and one in five said they thought so, but are not sure. Only 3.9% would like to get sick, and the pandemic to end practically for them. Probably the low number of people willing to become infected is due to the possibility of complications such as mechanical ventilation or death. These results are not surprising, given the rapid spread and lack of prevention and treatment of COVID-19 [7].

What will be the frequency of psychiatric illnesses during and after the pandemic can not be said at the moment. Data on the current pandemic began to be published in February this year, but data are still limited [8,9]. Despite the limitations available, there is already evidence that psychiatric morbidity has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly among front-line health workers in China [10]. To the symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress can be added the risk factors for mental health impairment - female gender, low social status, and residence in regions with high morbidity and mortality [11].

In addition to psychological support, interventions are needed in the early stages of the current pandemic to reduce anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder in the population [12,13]. Among the measures to promote the mental health and well-being of all proposed by the IASC, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies [14] are messages to the general public that it is normal for people to feel sad, difficult, worried, confused, frightened. or angry during a crisis; to have recommendations for hanging out with relatives and friends, even respecting the social distance; to maintain a healthy lifestyle, to avoid bad habits, to seek professional help if they feel overwhelmed, overtired, depressed or scared [15]. Adherence to anti-epidemic measures, moderate time spent on tracking information about the pandemic, trusting only reliable sources, and acquiring skills to deal with negative emotions are essential measures to maintain mental health and well-being.

Conclusion

Our results and published data on previous epidemics and pandemics have shown that affected populations respond by affecting mental health. Risk factors for deteriorating mental health include fear of infection, social distancing, loneliness, stigma, and declining incomes due to emergency crisis measures by the government. The guidelines of the official bodies for the preservation of mental health and psychosocial support in crises, such as the pandemic, once again emphasize the need to work at all levels to deal with the situation, as well as to take extraordinary measures for the most vulnerable groups in the affected populations.

References

- Briefing note on addressing mental health and psychosocial aspects of COVID-19 Outbreak - Version 1.1. Inter-Agency Standing Committee IASC Reference group for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings.

- Arlington VA (2013) American Psychiatric Association. Trauma- and stressor-related disorders. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th edn), 265-290.

- Park JS, Lee EH, Park NR, et al. (2018) Mental Health of Nurses Working at a Government-designated Hospital During a MERS-CoV Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 32: 2-6.

- Lee SH, Shin HS, Park HY, et al. (2019) Depression as a Mediator of Chronic Fatigue and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Survivors. Psychiatry Investig 16: 59-64.

- Shultz JM, Baingana F, Neria Y (2015) The 2014 Ebola Outbreak and Mental Health: Current Status and Recommended Response. JAMA 313: 567-568.

- Thompson RR, Garfin DR, Holman EA, et al. (2017) Distress, Worry, and Functioning Following a Global Health Crisis: A National Study of Americans' Responses to Ebola. Clinical Psychological Science 5: 513-521.

- Vasterman P, Yzermans CJ, Dirkzwager AJE (2005) The Role of the Media and Media Hypes in the Aftermath of Disasters. Epidemiol Rev 27: 107-114.

- Chan AO, Huak CY (2004) Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium-sized regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup Med 54: 190-196.

- Banerjee D (2020) The COVID-19 outbreak: Crucial role the psychiatrists can play. Asian J Psychiatr 50: 102014.

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. (2020) Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 3: e203976.

- Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF (2020) Rethinking online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr 50: 102015.

- Zhu Y, Chen L, Ji H, et al. (2020) The Risk and Prevention of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Infections Among Inpatients in Psychiatric Hospitals. Neurosci Bull 36: 299-302.

- Pfefferbaum B, North C (2020) Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med 383: 510-512.

- WHO (2020) SURVEY TOOL AND GUIDANCE: Monitoring knowledge, risk perceptions, preventive behaviours and trust to inform pandemic outbreak response.

- DiGiovanni C, Conley J, Chiu D, et al. (2004) Factors influencing compliance with quarantine in Toronto during the 2003 SARS outbreak. Biosecur Bioterror 2: 265-272.

Corresponding Author

Tsvetelina Velikova, MD, Ph.D, Department of Clinical Immunology, University Hospital Lozenetz, Kozyak 1 str, 1407 Sofia, Bulgaria.

Copyright

© 2020 Velikova T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.