Strategy Management of COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrative Review

Abstract

Objective: The objective of this paper is to analyze and evaluate public policies in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic in the world through publications and recommendations issued by countries and international organizations.

Method: We have suggested a research methodology based on expert opinion on the critical factors that determine the outcomes of national pandemic policies. Based on comprehensive literature review, three independent variables were calculated: The reach of public policy pandemic interventions, the timing of public policy interventions, and the success of public policy in motivating compliance with pandemic measures (e.g. Communication, safety and security coordination). The variables that ultimately condition the current mortality and morbidity rates of COVID-19 worldwide. We have collected information from various national and international health care guidelines and publications.

Results: Given the variability in growth rates of COVID-19 cases in different regions and countries, a number of criteria are proposed for the evaluation of quality improvement plans for COVID control: Potential for rapid implementation and completion; minimization of administrative and manpower burden required from stressed HCWs and healthcare institutions; effectiveness of and potential for revealing occupational risks; ability to identify inefficiencies in the management of known risks; and to monitor risks associated with transmission routes.

Conclusion: The COVID pandemic experience has taught us that the expansion of health systems requires the development of health practices based on an interdisciplinary vision, with outcomes oriented towards the dynamics of actions and the management of health problems. The central role of leadership and a strong organization are paramount in managing such crises.

Keywords

Strategy, COVID-19, Pandemic, Management

Introduction

The members of the coronavirus family have caused three major outbreaks in the past twenty years, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2002, the Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2012, and now the Coronavirus Disease 2019, named as COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 [1]. According to world meter data, [2] on 31 December 2020, the number of SARS-CoV-2 infected people globally was around 84 million, more than a million eight hundred thousand patients lost their lives, and more than a hundred thousand with serious critical health. This rapid spread of COVID-19 has prompted numerous community responses. Measures taken include closing schools, travel restrictions, banning public gatherings, strengthening health system facilities. Before the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries had their preparedness for pandemics assessed via the Global Health Security Index (GHSI) [3]. In its April 2020, COVID-19 Strategy Update WHO recommended that every country implement a comprehensive set of measures to slow down transmission and reduce mortality. Evaluating the performance of COVID-19 intervention systems in the implementation of these measures is very important in order to coordinate actions and reduce the negative effects of the spread of the pandemic. It requires an understanding of public health capacities, government actions, and community behaviors.

Taking action without such an assessment risks prolonging the pandemic. Efforts must be maintained to test as many people as possible, continue to improve tracing, treatment, and isolation activities [4]. World Health Organization (WHO) has issued several guidelines, started online courses and training sessions to raise awareness and preparedness regarding prevention and control of COVID-19 among HCWs [5].

The objective of this paper is to analyze and evaluate public policies in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic in the world through publications and recommendations issued by countries and international organizations, and to contribute to the discussion by identifying critical factors in the success/failure of public policies focusing on fighting the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, using a qualitative comparative policy analysis method as the main research tool. To evaluate the positive and negative aspects of experiences in service delivery, to adapt the services to changing conditions, and to take an organizational and holistic approach in solving the problems [6].

Methods

Research design

A systematic review of the literature using a narrative synthesis approach [7]. We opted for the qualitative method based on the interpretative approach. We have suggested a research methodology based on expert opinion on the critical factors that determine the outcomes of national pandemic policies.

Criteria for considering studies in the review

All peer-reviewed publication types including literature reviews, quantitative studies, qualitative studies, mixed-methods studies and discussion papers were included in the review. Included studies addressing the effect of Strategy management in COVID-19, and action plan and preparation against Covid-19, in English language.

Exclusion criteria

We have excluded papers that did not focus on strategy and action plan in COVID-19.

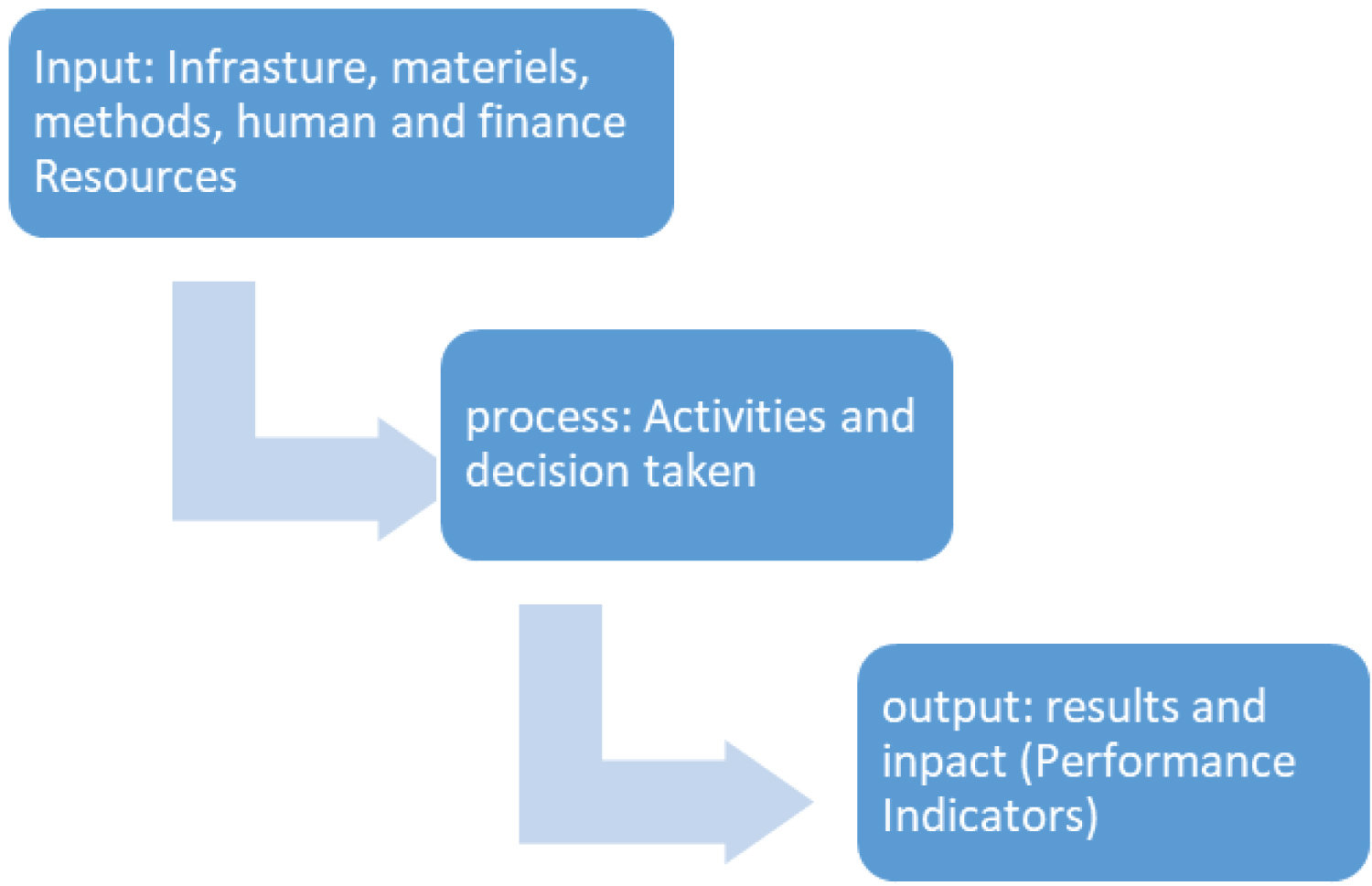

We advocated a systems approach (input, process and output) to describe the health care system (Figure 1).

The conceptual framework

Our conceptual framework had three main dimensions. First, health policy triangle was used to analyze the content, context, process and main actors involved in design, agenda setting and implementation of related policies [8]. We also used the Hall Model (legitimacy, feasibility and political support) to describe the components of agenda setting. Finally, we combined top-down and bottom up implementation theories (synthetizing approach) [9].

Both the data and the classification philosophy are inspired by the publications of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and the World Health Organization throughout the pandemic period. The Global Health Security (GHS) Index is intended to be a key resource in the face of increasing risks of high-consequence and globally catastrophic biological events and in light of major gaps in international financing for preparedness. The indicators and questions that compose the GHS Index framework also prioritize analysis of health security capacity in the context of a country's broader national health system and other national risk factors. The 140 GHS Index questions are organized across six categories: 1. Prevention; 2. Detection and reporting; 3. Rapid response; 4. Health system; 5. Compliance with international norms; 6. Risk environment [3]. Most of the variables are judged with objective and other subjective criteria, three independent variables are taken into account: The reach of public policy pandemic interventions, the timing of public policy interventions, and the success of public policy in motivating compliance with pandemic measures (e.g. Communication, safety and security coordination). The variables that ultimately condition the current dependent variables mortality and morbidity rates of COVID-19 worldwide. We know that this method has limitations (the data sources are not all equally reliable) but remains a way of understanding the subject.

Search strategy

The electronic databases were used to search for relevant articles: Medline, Cochrane, and Google scholar. The following search terms were used were Strategy management in COVID-19, COVID-19 Pandemic. The titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search strategy were independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (CY and GS). Full text copy of the different studies considered to be potentially relevant for the review was then retrieved for further examination. We have collected information from various national and international health care guidelines and publications.

Quality assessment

The study design of included publications was determined using the Medical Research Council guidance evidence hierarchy [10]. The methodological quality of individual studies was not assessed as this review aimed to examine the evidence regarding the core elements of, tools for, and barriers to performance evaluation rather than a review of effectiveness of performance evaluation systems. In addition, the majority of publications included in the review were discussion papers, which did not allow the use of a structured critical appraisal tool.

Data extraction and analysis

Content analysis was used in this review to provide a framework for data extraction and guide the synthesis of data from individual studies. This approach was chosen as it can be used to synthesize data from a diverse range of literature, [11] and is considered to be an appropriate method when data available are descriptive in nature [7], which was the case in this systematic review. The content analysis approach for this review drew on the systematic review techniques reported by Evans & Fitzgerald, is an established method in research and involves developing categories and coding the individual studies against these categories [12,13]. A series of steps were used to gather and analyses evidence from individual studies. Firstly, all included articles were read to develop an initial impression of the body of literature. Two reviewers worked collaboratively to identify recurring 'key issues' form individual studies, creating a list of initial categories, which informed the development of an extraction tool. Using a random sample of included studies, the initial categories were tested, revised as necessary, and then finalized by the two reviewers. Individual studies each contributed data related to a number of categories relevant to performance evaluation.

Results

Literature base

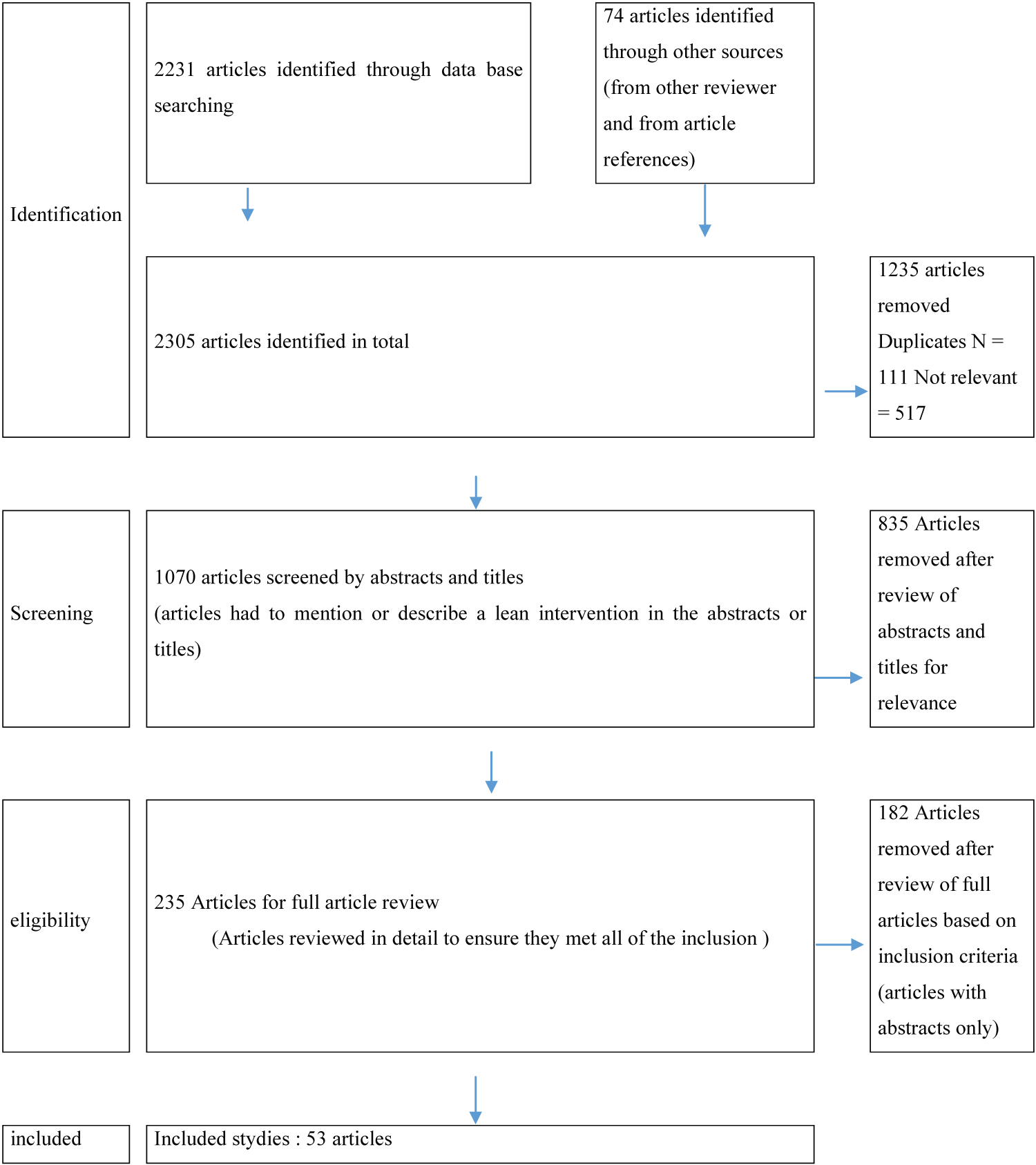

The database search yielded 2233 articles and 74 articles identified through other sources of which 1235 were excluded due to duplicates and selection criteria. 1070 articles screened by abstracts and titles. After scrutiny 835 Articles removed after review of abstracts and titles for relevance were further excluded; 235 Articles for full article review (Articles reviewed in detail to ensure they met all of the inclusion 182 Articles removed after review of full articles based on inclusion criteria (articles with abstracts only) leaving 53 articles for inclusion in the review. A consort diagram for the literature search is shown in Figure 2.

Risk factors related to Covid-19

Two groups of risk factors have been identified, those related to the transmission of the virus and those related to the complications of the disease [14].

Risk factors for contamination by the virus

Three risk factors have been identified as the most important: (a) Population density [15], (b) Precarious housing, and social exclusion. The risk of infection and death related to Covid-19 is higher in the most disadvantaged regions [15]. (c) Household contacts are more numerous and travel/travel is frequent [16].

Risk factors for complications

The risk factors identified are: (a) Age: People aged 50 and over are most affected by the severity of the disease [16,17]. (b) Gender: Women are less likely to develop complications from HIV infection than men [18]. (c) Co-morbidities: The risk of coronavirus infection is higher in people with one or more chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory system diseases, kidney disease, obesity, and malignant or immune-compromised tumors [19]. The risk mitigation measures implemented by many countries have been grouped into the following categories: (1) Mobility Restrictions; (2) Socio-economic restrictions; (3) Physical Distancing; (4) Hygiene Measures (5) Communication.; (6) International support mechanisms [20,21].

Surveillance

Epidemiological surveillance is based on anticipation, early detection, and response to an unusual increase in the number of cases. Setting up a surveillance system for a new epidemic is considered an essential intervention in the fight against the disease. Data from monitoring systems provide information to identify transmission chains and facilitate evidence-based decision-making. Comparing the effectiveness of surveillance systems for the COVID-19 epidemic in different countries remains very difficult; it appears that the WHO surveillance system remains very effective in detecting, recording, monitoring, updating and sharing information [22]. Active and reactive case detection and close contact tracing. Epidemiological investigations to prevent the spread of the disease. Mechanisms that are based on knowing how to assess, plan, implement and maintain risk mitigation measures, while appropriately deciding who needs to be involved, making decisions about the chain of command, and channeling communication [23].

Discussion

According to Mattiuzzi, et al. [24] the pandemic revealed many of the systems' faults and uncovered opportunities for improvement: (1) The existing public healthcare system is not adequate, with major deficiencies in managing various aspects of public health concerns, especially in the field of communicable diseases; (2) Emergency departments suffer from adequate infrastructure and resources to cope with the increase in critical patients; (3) System efficiency is not achieved and process overload and redundancy hinder good care; (4) Health personnel care is essential for optimal system performance [25]. It is very important to consider the sacrifices made by health officials, patients, their families, and society to bring about positive change in health care. A number of these changes have already begun to create a "new normal" in health care [26]. The opportunities to be seized to create a better health care system. (1) Reforming the health care system from one based on acute and chronic disease management to one based on prevention, prediction and population oriented. (2) To reorganize the health care system to make it leaner, by re-engineering processes, eliminating waste, using technology, and providing remote care. (3) Motivating staff by identifying and addressing their concerns early. (4) Encouraging research and innovation by building on the experience gained during the pandemic. Staines, et al. [27] propose a five-step strategy through, which we can contribute significantly during a pandemic to support patients, staff, and organizations: (1) Strengthen the system through readiness assessment, a training program, and a personnel security system. (2) Commit to close collaboration among all stakeholders to ensure that solutions are appropriate and jointly implemented. (3) Work to improve care through the introduction of teamwork and the development of clinical decision support. (4) Reduce the harm by proactively managing risk to both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients. (5) Energize the learning system in order to seize opportunities for improvement, adapt very quickly, and develop resilience. This pandemic poses innumerable challenges to the medical community with little scientific evidence to manage our uncertainty [28]. (1) Complexity between policy, science; and practice, and knowledge management, and the sharing of good practices in the area of risk management [29]. (2) Haghani, et al. [30] identify ten major dimensions of safety that so far have attracted the attention of the scientific community: Medicine, treatment and vaccine safety; blood safety; pregnancy safety; surgery and anesthetic safety; occupational safety of healthcare workers; patient transport and visit safety; biosafety of medical facilities; food safety; social safety; and mental/ psychological health and domestic safety. The recovery should mark the beginnings of a global transformation to strong, sustainable, inclusive, and resilient economic development and growth, if we are to limit the impact on the poor and vulnerable, make progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and manage the immense climate change risks.

According to Saurin A [31], the analysis of the current crisis is based on five guidelines to deal with the complexity that is: multiple perspectives in decision making, variability in the visibility of processes and outcomes, understanding the gap between the design and execution of work, and predicting and monitoring unintended consequences. According to Galsworthy, [32] providing visibility into processes and results helps reduce perceived complexity, enable real-time performance monitoring, and share useful information freely.

According to Rozner [33], well designed key performance indicators (KPIs) help field hospital decision-makers as follows: Set performance standards and targets to motivate continuous improvement, measure and report on improvements over time, compare performance across different geographic locations, benchmark performance against peers or regional and international standards, and enable stakeholders to independently judge health sector performance. Fisher, et al. [34] show that it is better to benchmark countries during a pandemic in ways that allow information on outcomes and performance to be obtained, analyzed, reported, and used in real-time. According to Ahmad, et al. [35], the top priorities globally are to tackle the public health emergency and prevent or limit a COVID-19 resurgence; to protect the most vulnerable, particularly in relation to employment; and to give strong support to the banking system and supply of finance. The role of primary care in epidemic management is also discussed and, finally, we offer our recommendations to the primary care system in optimizing their preparedness for an emergency response to the current coronavirus epidemic as well as future epidemics [36].

The management strategy of the COVID-19

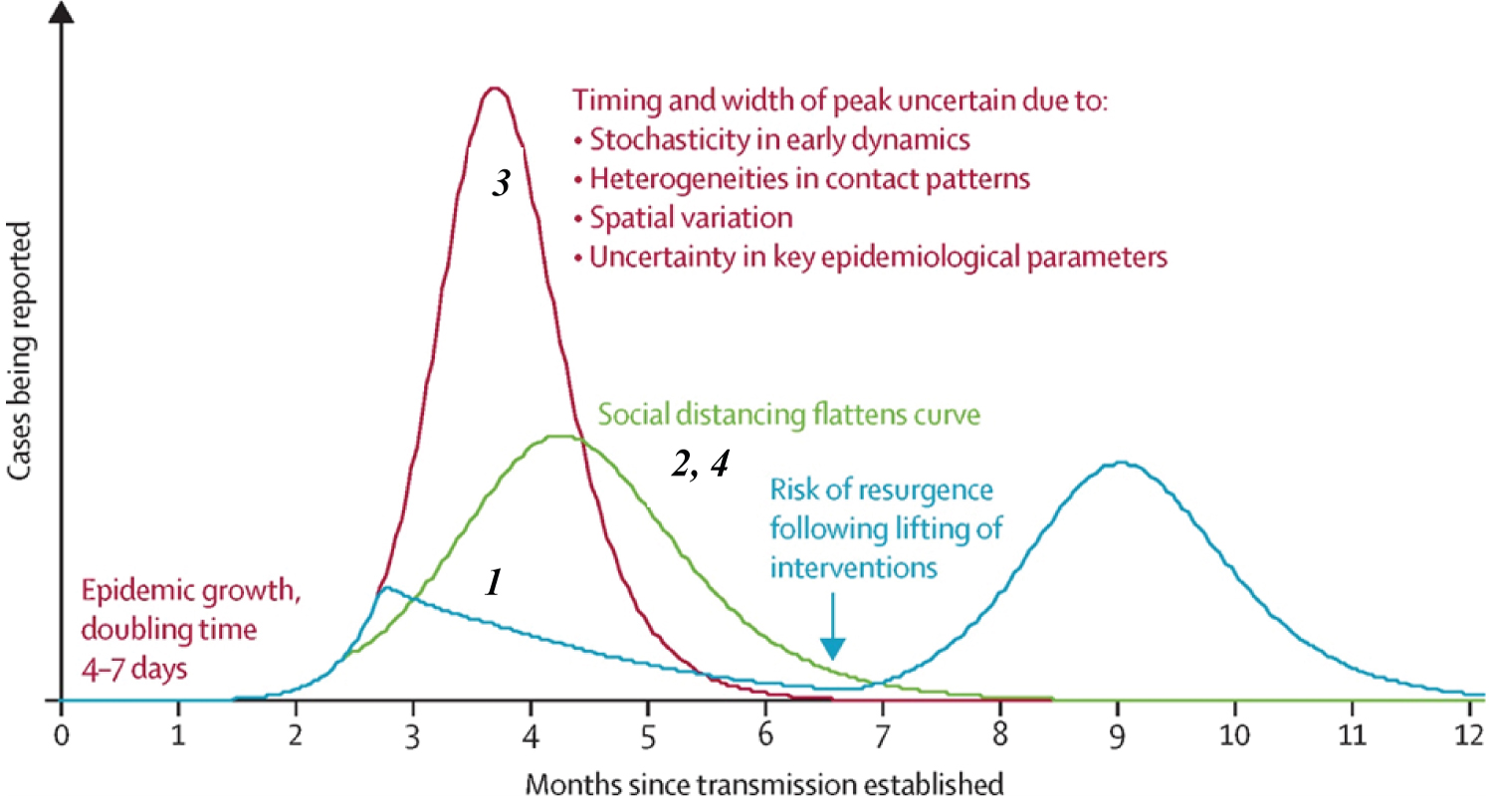

The choice of management strategies depends on multiple factors, including national resource levels, the capacity of the health system, and its responsiveness to the pandemic [34,37]. To assess the response to the crisis, one must ask how prepared the authorities were, how they made sense of the situation, how they collaborated across borders and took crucial decisions to manage the crisis, and how they communicated with citizens [38]. According to Scopetti, et al. [39] the management of the COVID-19 epidemic in similar contexts is extremely complex for three main reasons. First, the characteristics of the population being assisted are not the same. Second, the small number of health professionals, mainly nurses, involved in the care process. Third, the difficult access to biological tests and equipment, which hampers diagnosis and poses serious problems regarding patient and professional safety. The health systems have generally been able to adapt [40]. According to Legido Quigley, et al. [41] the core dimensions of the resilient health systems and their responses to the COVID-19 epidemic: (a) Surveillance systems were readjusted to identify potential cases while public health staff identified their contacts, (b) Intra-governmental coordination was improved, (c) All adapted financing measures so that all direct costs for treating patients are borne by the governments, (d) The health systems developed plans to sustain routine health-care services, but the integration of services has been problematic, (e) Critical care treatment and medicines have been available for patients with COVID-19, but adequate supplies of personal protective equipment in hospitals and face masks in the community are a key concern, (f) Training and adherence to infection prevention and control measures in hospitals have largely been appropriate, (g) Management of information systems is comprehensive in all locations, (h) Accurate, and transparent risk communication is essential and challenging in emergencies because it determines whether the public will trust authorities more than rumors and misinformation, and (i) The political environment and differences in communities and their moods and values are important. Christensen, et al. [42] enumerate two core questions that arise in connection with organizing for societal security and crisis management: First, governance capacity (preparedness or analytical capacity, coordination, regulation, and implementation or delivery capacity) to provide effective crisis management, and second, governance legitimacy (citizens' trust in government and concerns such issues as accountability, support, expectations, and reputation) [43] (Figure 3).

The prevention strategies

Three strategies have become recognized as the "backbone" of the response to COVID-19: testing, isolation, and contact tracing [2]. The prevention strategies are based on the general principles of infection control as well as the experience of clinical risk managers and healthcare professionals who were involved in managing these facilities during the pandemic.

The assessment of healthcare systems should be conducted using the Patient Safety Systems Engineering Initiative model to correlate design (structure) and patient safety (outcomes) across the processes of care. The assessment of structural aspects (e.g., physical environment, organizational culture, infection surveillance systems) should be conducted with consideration of the specifics of the processes of care and the operational effectiveness of the professionals involved in providing assistance, producing results that can be expressed in terms of expected outcomes. Training of health care professionals should cover hand and respiratory hygiene, use of appropriate personal protective equipment, good safety practices, safe waste disposal, proper laundry management, cleaning, and sterilization of equipment. Similar measures can help achieve desired outcomes such as patient safety, worker well-being, reduced risk of infection, and improved organizational performance [44]. According to Li, et al. [45] four key capacities are needed: (1) Communities must have the capacity to detect cases early and interrupt transmission chains. (2) Communities need the capacity for isolating individuals with COVID-19 and keeping contacts in quarantine. (3) The capacity for rapid and thorough tracing of the contacts of cases. (4) Public health laws need to be in place, understood, and accepted by the public to reinforce behaviors that are necessary for community wellbeing.

Communication and Leadership

The health care system faces at least two important challenges. One is the uncertainty caused by the lack of evidence, and the other is the high number of destructive rumors being propagated [46]. The combination of these two challenges can lead to a devastating public panic, a situation that could lead to severe disruption of social functions and eventually more complicated conditions and even failure of crisis control efforts [47,48]. Effective and timely communication with the public was vital in raising awareness and mitigating risks via public education on reducing transmission [36]. However, some gaps were identified which included the lack of a national and up-to-date database of identified cases and the protection of staff handling samples in the reference laboratory [36]. While countries have different governance mechanisms, a few governance decisions in respective countries did make a difference, along with strong community solidarity and community behavior.

Communication has proven to be a very important element in the fight against the pandemic. COVID-19 is new as a pandemic and people's expectations are very high. They expect consistent, honest and accurate communication. Effective communication strategies must be developed that use different means and methods to reach all language and cultural groups and all levels of education in the target community. All leaders need to work together for the best results: the virus thrives when decisions are inconsistent or non-transparent. Among other things, leadership must be cross-sectoral and flexible, adapting to new information as it emerges [34]. A combination of good leadership and strong public health systems with a fully engaged community can result in well-articulated and monitored response capacities. When response systems perform well, they allow for the successful removal of any movement restrictions and the opening of borders between and within countries [34].

Coordination

According to WHO (2020), the most important priorities in the fight against COVID-19 are to strengthen coordination mechanisms, including in the health, transport, travel, trade, finance, security, and other sectors, to raise public awareness of its active role in the response, and to engage with key partners to develop national and sub-national preparedness and response plans. Public trust in the healthcare system is a critical necessity of management in public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic [49]. To meet the growing demand for contaminated patients, the need for interprofessional skills is very high, in terms of conflict management, problem solving between work teams in addition to managing patient care [50]. Consequently, there is a worldwide increasing need for the development of complex practices that are based on inter-disciplinarity and inter-professionalism in order to achieve quality results in health care, through collaboration among professionals and expansion of interdisciplinary health care models [51]. Furthermore, there is an increasing perception that unidisciplinarity achieves ineffective results in front of the complexity of the health process and the illness of communities and population [51]. Although it proved to be a major challenge to existing research studies, this pandemic has allowed us to strengthen the use of technology, introduce new initiatives and large-scale collaborations.

Risks and Security

Global health security initiative (GHSI) 2001 has been very active recently in the bio field, various national or regional Centers of Disease Control [52]. Despite preventive measures to address public health risks and the regulatory efforts of many countries, the current COVID-19 epidemic reminds the world of the vulnerability to natural and man-made chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear hazards and the importance of mitigation measures [20]. For adequate risk management, the establishment of a coordinating committee, the implementation of a surveillance program, the identification of appropriate premises and equipment, the application of universal precautions, the adaptation of care plans to reduce the possibility of contagion, and the protection of operators and staff training initiatives are considered essential [53]. Occupational risk studies for COVID-19 are difficult and have only recently begun [54]. The SEIPS model "Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety" is a framework for understanding the systemic factors that contribute to patient safety by designing processes and improving outcomes [44]. One of the essential missions of infection control programs in health care facilities is to reduce the risk of occupational infections among health care workers (HCWs). According to Marmor, et al. [54] the evaluation of COVID-19 control quality improvement plans should be based on the following criteria: The potential for rapid implementation and completion; minimization of administrative burden; effectiveness of disclosure of occupational risks; ability to identify inefficiencies in the management of known risks; and monitoring of risks associated with transmission routes. Common strategies to prevent nosocomial transmission include outlining a clear plan for providing essential services during the pandemic, with dedicated COVID-19 beds and units [55]; separation of healthcare facilities for the treatment of infected COVID-19 patients and non-COVID-19 patients and increasing intensive care bed capacity [56]. Given the similarity of measures introduced by governments, the results suggest that the success of measures to encourage compliance may be critical factors in containing the pandemic [57].

Complexity of a Pandemic

A pandemic is a complex phenomenon, involving many aspects, parameters, and appropriate boundary conditions, and it probably cannot be described by simple bivariate correlations [58]. Containment policies are likely to remain in place much longer than expected, depending on the speed of reproduction of SARS-CoV-2 and the proximity of the collapse of national health systems. Granted that further extension of restrictions could be resisted by much of the population and reduce people's compliance with distancing rules [59]. According to Bontempi, et al. this pandemic demonstrates the need for a comprehensive inter- and transdisciplinary approach, involving a variety of experts, not only from the medical and natural sciences, but also from engineering, political, economic, social and demographic disciplines [58]. The failure to contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide can be largely attributed to a lack of awareness of the importance of airborne transmission of the virus via aerosols. Several inappropriate policy management strategies, which often occurred early in the spread of the virus [60].

Limits

Our study has several limitations. Like any policy intervention, the effect of the strategies is likely to depend heavily on the local political and social contexts, cultural factors such as trust and loyalty, structural factors such as coordination and regulatory capacity, and stronger evidence-based knowledge about the corona pandemic will be needed.

Conclusion

The COVID pandemic experience has taught us that the expansion of health systems requires the development of health practices based on an interdisciplinary vision, with outcomes oriented towards the dynamics of actions and the management of health problems. The central role of leadership and a strong organization are paramount in managing such crises. All countries of the world have sought to introduce appropriate containment measures and governance structures, have taken steps to support health care delivery and financing, and have developed and implemented management plans and structures. However, there are gaps in the coordination of services, access to adequate medical equipment, risk communication, and public confidence in the government.

Lessons Learned

The main lesson learned from the COVID crisis is the following:

- Pandemic preparedness was achieved quickly and efficiently.

- The spread of fake news and misinformation constitutes a major unresolved challenge.

- The trust of patients, health-care professionals, and society as a whole in government is of paramount importance for meeting health crises.

- Successful management of a pandemic must prioritize measures to protect citizens from infection without increasing negative economic impacts.

- Collaboration between countries, political authorities and international organizations is necessary.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Source of Funding

There is any sources of funding.

References

- Xie P, Ma W, Tang H, et al. (2020) Severe COVID-19: A review of recent progress with a look toward the future. Front Public Health 8: 189.

- WHO (2021) Coronavirus update (Live): 94,376,856 cases and 2,019,298 deaths from COVID-19 virus pandemic-worldometer.

- Center for health security (2019) The global health security index: Building collective action and accountability.

- Anderson RM, Hollingsworth TD, Baggaley RF, et al. (2020) COVID-19 spread in the UK: The end of the beginning? Lancet 396: 587-590.

- Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J, et al. (2020) Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) knowledge and perceptions: A survey of healthcare workers. Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS).

- Bulduklu Y, Yesil M (2020) Reflections on the Pandemic in the Future of the World. 2: 959-986.

- Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M (2012) Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. Journal of Development Effectiveness 4: 409-429.

- Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, et al. (2008) 'Doing' health policy analysis: Methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy Plan 23: 308-317.

- Buse K, Mays N, Walt G (2012) Making health policy. (2nd edn), McGraw-Hill Education, UK.

- Craig P, Dieppe, Macintyre S, et al. (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new medical research council guidance. BMJ 337: a1655.

- Pope C, Mays N, Popay J (2007) Synthesising qualitative and quantitative health evidence: A guide to methods. McGraw-Hill Education 30: 330-331.

- Evans D, FitzGerald M (2002) Reasons for physically restraining patients and residents: A systematic review and content analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 39: 735-743.

- Mays N, Pope C, Popay J (2005) Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 10: 6-20.

- Aazi FZ, Audibert M, Bouazizi Y, et al. (2020) Crise sanitaire et répercussions économiques et sociales au Maroc : évaluations et analyses d'un collectif de chercheurs. report.

- Lusignan de S, Dorward J, Correa A, et al. (2020) Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 among patients in the oxford royal college of general practitioners research and surveillance centre primary care network: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 20: 1034-1042.

- Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. (2020) Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in shenzhen, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 20: 911-919.

- Liu W, Qi Zhang, Junbo Chen, et al. (2020) Detection of Covid-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med 382: 1370-1371.

- Zhao S, Lin Q, Ran J, et al. (2020) Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: A data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak. Int J Infect Dis 92: 214-217.

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. (2020) Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 180: 934-943.

- de Bruin BY, Lequarrea AS, McCourt J, et al. (2020) Initial impacts of global risk mitigation measures taken uring the combatting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Safety Science 128: 104773.

- Gostic K, Gomez AC, Mummah RO, et al. (2020) Estimated effectiveness of symptom and risk screening to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Elife 9: e55570.

- Phelan L, Katz R, Gostin LO (2020) The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: Challenges for global health governance. JAMA 323 8: 709-710.

- Di Nucci MR, Brunnengräber A, Isidoro Losada AM (2017) From the "right to know" to the "right to object" and "decide". A comparative perspective on participation in siting procedures for high level radioactive waste repositories. Progress in Nuclear Energy 100: 316-325.

- Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G (2020) Which lessons shall we learn from the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak? Ann Transl Med 8: 48.

- Jazieh RA (2020) COVID-19 pandemic as a catalyst for healthcare transformation: Finding the silver lining in a global catastrophe. Glob. J Qual Saf Healthc 3: 117-118.

- Jazieh R, Kozlakidis Z (2020) Healthcare transformation in the post-coronavirus pandemic Era. Front Med 7: 429.

- Staines A, Amalberti R, Berwick DM, et al. (2021) COVID-19: Patient safety and quality improvement skills to deploy during the surge. Int J Qual Health Care 33: mzaa050.

- Kodadek LM, Berger JC, Haut ER (2020) Guidance vs. guidelines: The role of evidence-based medicine in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Patient Saf Risk Manag 25: 216-218.

- Daszak P, Olival KJ, Li H (2020) A strategy to prevent future epidemics similar to the 2019-nCoV outbreak. Biosaf Health 2: 6-8.

- Haghani M, Bliemer MCJ, Goerlandt F, et al. (2020) The scientific literature on Coronaviruses, COVID-19 and its associated safety-related research dimensions: A scientometric analysis and scoping review. Safety Science 129: 104806.

- Abreu Surin T (2021) A complexity thinking account of the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for systems-oriented safety management. Safety Science 134: 105087.

- Galsworth GD (2017) Visual workplace : Visual thinking. (2nd edn), Productivity Press.

- Rozner S (2013) Developing key performance indicators-a toolkit for health sector managers. HFG.

- Fisher D, Teo YY, Nabarro D (2020) Assessing national performance in response to COVID-19. The Lancet 396: 653-655.

- Ahmad E, Stern N, Xie C (2020) From rescue to recovery: Towards a sustainable transition for China after the COVID-19 pandemic. 20.

- Shehata M, Zhao S, Gill P (2020) Epidemics and primary care in the UK. Fam Med Community Health 8: e000343.

- Haffajee RL, Mello MM (2020) Thinking Globally, Acting Locally-The U.S. Response to Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382: e75.

- Galaz V, Tallberg J, Boin A, et al. (2017) Global governance dimensions of globally networked risks: The state of the art in social science research. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 8: 4-27.

- Scopetti M, Santurro A, Tartaglia R, et al. (2020) Expanding frontiers of risk management: Care safety in nursing home during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Qual Health Care mzaa085.

- Blanchet K, Nam SL, Ramalingam B, et al. (2017) Governance and capacity to manage resilience of health systems: towards a new conceptual framework. Int J Health Policy Manag 6: 431-435.

- Legido Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, et al. (2020) Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 395: 848-850.

- Christensen T, Lægreid P (2020) Balancing governance capacity and legitimacy: How the norwegian government handled the COVID-19 crisis as a high performer. Public Adm Rev 80: 774-779.

- Lodge M, Wegrich K (2014) The problem-solving capacity of the modern state: Governance challenges and administrative capacities. Oxford University Press.

- Carayon P, Wooldridge A, Hoonakker P, et al. (2020) SEIPS 3.0: Human-centered design of the patient journey for patient safety. Appl Ergon 84: 103033.

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. (2020) Early transmission dynamics in wuhan, china, of novel coronavirus-Infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med 382: 1199-1207.

- Baize S, Pannetier D, Oestereich L, et al. (2014) Emergence of zaire ebola virus disease in guinea. N Engl J Med 371: 1418-1425.

- Rolison JJ, Hanoch Y (2015) Knowledge and risk perceptions of the Ebola virus in the United States. Preventive Medicine Reports 2: 262-264.

- Böl G (2016) Risk communication in times of crisis: Pitfalls and challenges in ensuring preparedness instead of hysterics. EMBO Rep 17: 1-9.

- Vardanjani HM, S HeydariT, Dowran B, et al. (2020) A cross-sectional study of Persian medicine and the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran: Rumors and recommendations. Integrative Medicine Research 9: 100482.

- Adriano da Costa Belarmino A, Maria Eunice Nogueira Galeno Rodrigues, Saiwori de Jesus Silva Bezerra Dos Anjos, et al. (2020) Collaborative practices from health care teams to face the covid-19 pandemic. Rev Bras Enferm 73: e20200470.

- Ana Wládia Silva de Lima, Fábia Alexandra Pottes Alves, Francisca Márcia Pereira Linhares, et al. (2020) Perception and manifestation of collaborative competencies among undergraduate health students. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 28: e3240.

- McCloskey, Dar O, Zumla A, et al. (2014) Emerging infectious diseases and pandemic potential: status quo and reducing risk of global spread. Lancet Infect Dis 14: 1001-1010.

- Tartaglia R (2020) Patient safety recommendations for covid-19 epidemic outbreak: Lessons from the italian experience. Global Clinical Engineering Journal J 2: 7-30.

- Marmor M, DiMaggio C, Friedman Jimenez G, et al. (2020) Quality improvement tool for rapid identification of risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infectin among healthcare workers. J Hosp Infect 105: 710-716.

- Elizabeth Brindle M, Gawande A (2020) Managing COVID-19 in surgical systems. Ann Surg 272: e1-e2.

- Phua J, Li Weng, Lowell Ling, et al. (2020) Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med 8: 506-517.

- Chubarova T, Maly I, Nemec J (2020) Public policy responses to the spread of COVID-19 as a potential factor determining health results: A comparative study of the Czech Republic, the Russian Federation, and the Slovak Republic. Cent Eur J Public Policy 14: 60-70.

- Bontempi E, Vergalli S, Squazzoni F (2020) Understanding COVID-19 diffusion requires an interdisciplinary, multi-dimensional approach. Environmental Research 188: 109814.

- Gollwitzer M, Platzer C, Zwarg C, et al. (2021) Public acceptance of Covid-19 lockdown scenarios. Int J Psychol 56: 551-565.

- Bontempi E (2021) The europe second wave of COVID-19 infection and the Italy "strange" situation. Environ Res 193: 110476.

Corresponding Author

Zaadoud Brahim, Clinical Neurosciences Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fez, Morocco, Tel: 212-661-624-913.

Copyright

© 2021 Brahim Z, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.