Work at Home and Psychological Wellbeing of Women with and without Children During COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic has had serious effects on women's mental health, with strongest effects reported for women living with children. The present study aimed at understanding how the work life reorganization of women with and without minors affected their levels of anxiety and depression. In addition, it investigated the potential protective role of perceived social support.

Methods: With an online survey administered to 678 women, the study investigated whether having children or not, work condition (work-at-home and go-to-work) and perceived social support, were associated with women's levels of anxiety and depression.

Results: Women with children experienced, when working at home, higher levels of depression and anxiety than when going to work, while an opposite pattern was present for women without children. Going to work was associated with higher depression and anxiety for women without children than for women with children. In addition, social support was found to be a protective factor against anxiety and depression, with differing effects.

Conclusions: The results of this study suggest that different work solutions should be implemented based on individual needs and characteristics to prevent the emerge of anxiety and depression.

Keywords

Women, COVID-19, Mother's wellbeing, Social support, Work at home, Children, Anxiety, Depression

Literature Review

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries around the world have implemented various procedures and regulations aimed at reducing contagion, profoundly changing the social life of individuals [1]. These procedures include the obligation to maintain social distancing and to wear personal protective equipment, and the closure of many activities. Consequently, many companies have reviewed their working methods by adopting new organizational strategies of work and incentivizing work at home. This work modality was encouraged especially for parents, since schools and many children facilities closed, and work at home was considered a solution to help adults looking after children.

However, working from home could also represent a source of stress affecting people well-being, due to the less social support received from colleagues and to the difficulty in disengaging from work [2]. This might be particularly true for parents who report difficulties in balancing work with childcare while working at home [3] with an increased rate of work-family conflict [4].

Studies conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic reported high levels of stress and depression in parents [5] with strongest effects on women [6,7] particularly women with children at home [8]. When examining the effect of work at home during the pandemic on parents, [9] found that mothers who were working at home exhibited higher levels of anxiety, loneliness, and depressive feelings than fathers. Taken together, these studies suggest that work at home might have affected adults' well-being during the pandemic differently according to their family condition.

Since working at home is a modality still incentivized by many institutions and will probably be permanently applied, there is a growing need to understand its effects on mental health and the factors that influence the psychological adjustment in such modified life and work conditions. The present study aimed to contribute to this line of research by exploring the impact of working modalities and social support on the symptoms of anxiety and depression of women with and without children. We expect that work at home represents a more difficult experience for women with children (rather than women without children) due to their increased difficulties in balancing work and family duties, with a protective role of perceived social support.

Material and Method

Participants

A total of 2387 participants completed the online survey, 679 of which (Gender: F = 100%; Age: M = 42.15 y, SD = 9.48 y) met the requirements for participating in the study. Men, those who did not complete the entire survey, those who were already not working before the lockdown or who stayed at home without working, and those who spent the lockdown alone were excluded. The distribution by geographical area reflects the typical distribution of the Italian population. Participants were divided into two groups: women who spent the lockdown with minors (children younger than 16 years old) (n = 323) and those who spent it without minors (n = 355). The mean age of women with minors was 43.94 y (SD = 6.5 y) and 54.2 % of them had earned at least a bachelor's degree. As for those without minors, the mean age was 40.52 y (SD = 11.31 y), 46.1% of them had earned at least a bachelor's degree, and 49% of them spent the lockdown with their partner, 32.4% with their parents, and 18.6% with other nonfamily adults

Procedure and Measures

Data were collected with an online survey in June 2020, at the end of the first lockdown imposed by the government started on March 9th, 2020. Participants were required to indicate their actual work modality: Go to work or work at home. Next, participants were asked to indicate the people with whom they spent the lockdown, if with minors or only with other adults. Socioeconomic status and age of children were not collected.

Anxiety and Depression: Participants completed the Anxiety and Depression scales of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) [10] consisting of 14 items (7 for each scale) rated on a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = Never to 4 = Always). Cronbach's alpha was 0.83 for the anxiety and 0.87 for the depression scale.

Perceived Social Support: Participants completed the Multidimensional Scale for Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) [11] consisting of 12 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree). Cronbach's alpha was 0.92.

Results

Univariate Regression Models

Two univariate regression models (Table 1) were conducted using having children or not, the modality of work (work at home, go to work), perceived social support, and the interaction between having children or not and the modality of work as predictors of anxiety and depressive levels. For continuous variables we used standardized z-scores. As the predictor working modalities was a categorical variable, we recoded the variables considering work at home values as a reference point.

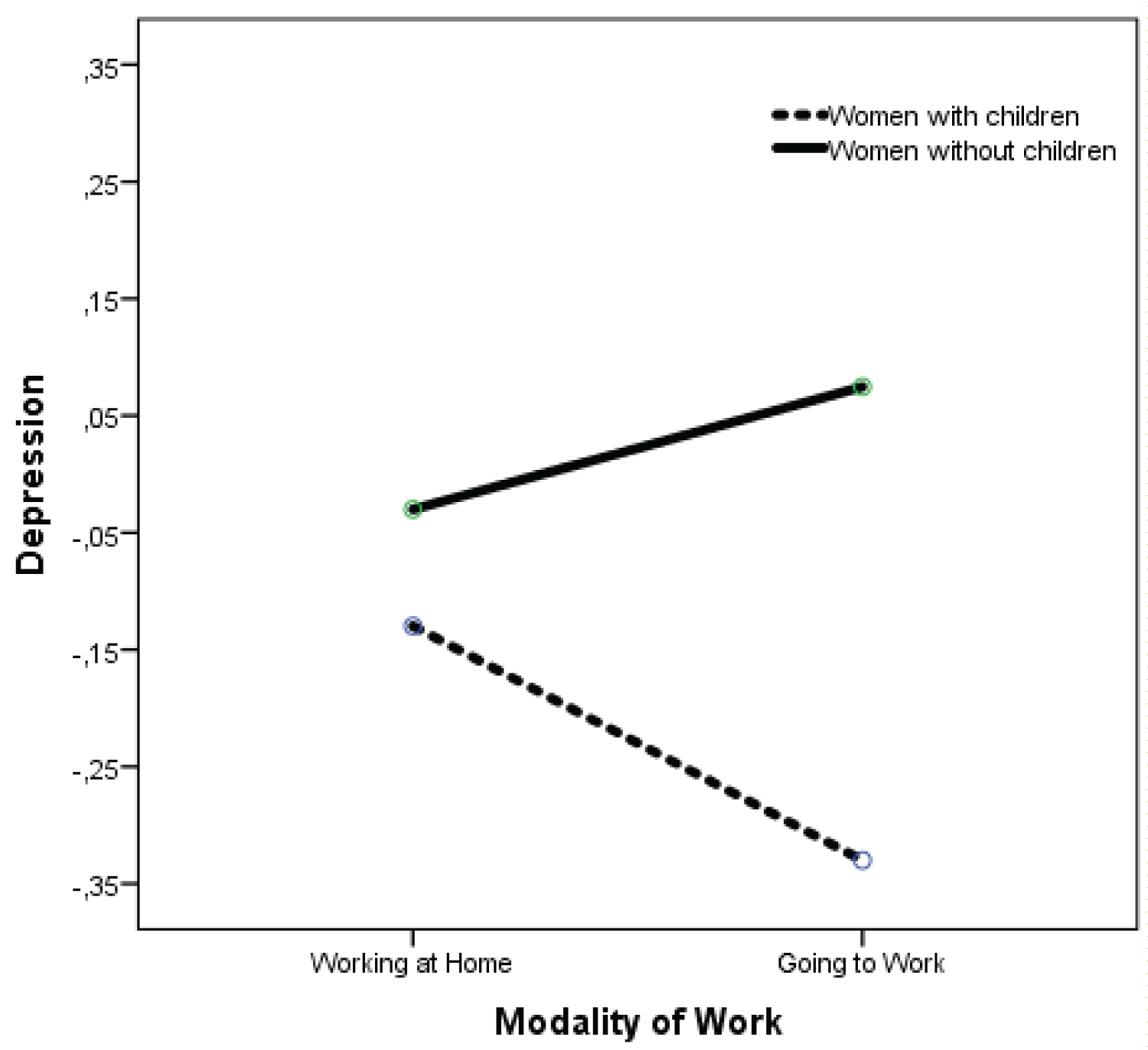

Depression: The main effect of perceived social support, F (1,677) = 38.84 p < 0.00, was significant. Higher levels of perceived social support were associated with lower levels of depression (ß = -0.017 p < 0.00). The effect of the interaction between having children or not and the modality of work F (1, 677) = 4.17p = 0.04 was significant. While no differences between the groups were present in the working at home modality, women with children who went to work reported lower levels of depression (M = -0.33; SD = 0.08) than women with children who worked from home (M = -0.13; SD = 0.06) (Figure 1).

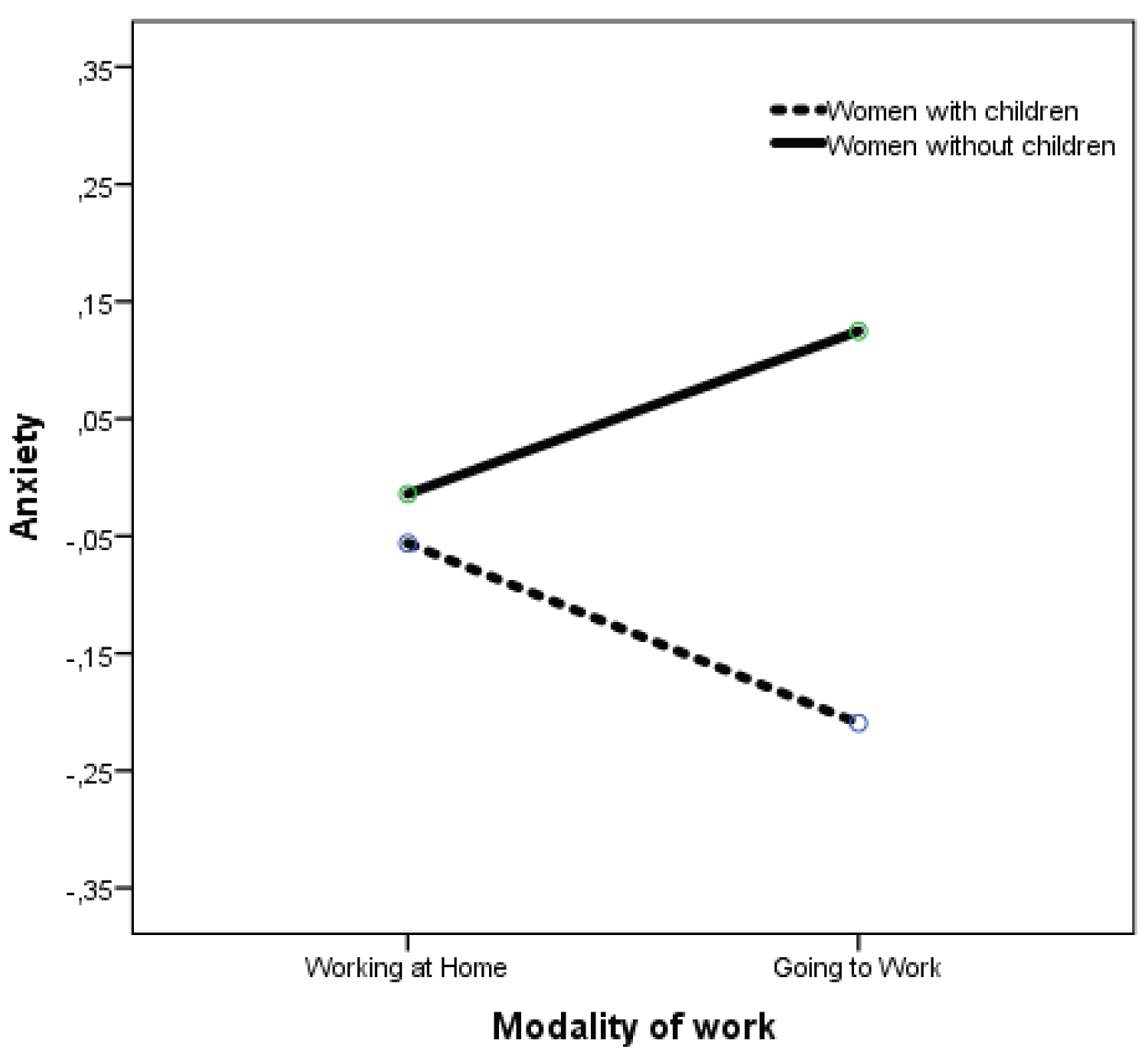

Anxiety: The main effect of perceived social support F (1,677) = 7.29 p < 0.01, was significant. Higher level of perceptions of social support are associated with lower levels of anxiety (ß = -0.008 p < 0.01). The main effect of having or not children was significant F (1,677) = 5.96 p < 0.01. Women without children reported higher levels of anxiety (M = 0.05; SD = 0.05) than women with children (M = -0.133; SD = 0.05). The interaction between having children or not and work modality was trending toward significance, F (1,677) 3.59 p = 0.058. Women with children who went to work reported lower levels of anxiety (M = -0.210; SD = 0.083) than those who worked at home (M = -0.056; SD = 0.07). Women without children who went to work (M = 0.125; SD = 0.090) reported higher levels of anxiety than those who worked from home (M = -0.014; SD = 062) (Figure 2).

Discussion

Our results showed that work modalities and perceived social support had an impact on women's wellbeing during COVID-19 lockdown, with some specificities and differences between women living with children and those who did not. In the group of women with minors, work at home was associated with higher levels of depression compared to go to work. For women with children, working at home might exacerbate the work-family conflict, and the difficulty to disengage from work commitments when working at home might be particularly evident for mothers who have to take care of their children. On the other side, working at home was associated with lower levels of depression than going to work in the group without minors. This may be due to the social support that can come from co-workers which helps reduce depression levels. Regarding anxiety levels, women with minors reported lower levels of anxiety than women without minors. In addition, women with minors who went to work showed lower levels of anxiety than women with minors who worked at home. Having these women to deal with balancing work, childcare, and housework, it may be that the difficulty of optimally dividing work-family schedules and roles may increase anxiety levels [12].

Consistent with the results of [13-15] who found that support was significantly and negatively associated with psychological well-being, we showed that the level of perceived social support received by others resulted as a protective factor both on anxiety and depression with different magnitudes of effects.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that the impact of occupational conditions on women's mental health varies also according to the presence of children or not. Interestingly, work at home was a source of a distress for women with children, suggesting that different solutions should be found to help parents dealing with the continuous lack of educational services and school closures that still are often necessary to reduce contagion. Given the strong effects of perceived social support on the levels of anxiety and depression, employers should reflect on the characteristics of their employees' needs according to their conditions, creating social support networks with tailored support programs to increase, especially in women with children, the sense of belonging to the group and decrease the sense of abandonment. Governments, on the other side, should improve the services and help given to working mothers in order to avoid the sense of being alone dealing with balancing work and care giving duties. It is recommended that further exploration of the phenomenon is needed after several other months. Future research is needed to confirm these patterns.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The work was partially supported with PON funding (MIUR, AIM 1811283-3) and the Department of Excellence MIUR funding awarded to “G. d'Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Song Y, Gao J (2020) Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. J Happiness Studies 21: 2649-2668.

- Kaduk A, Genadek K, Kelly EL, et al. (2019) Involuntary vs. voluntary flexible work: Insights for scholars and stakeholders. Community, Work & Family 22: 412-442.

- Vander Elst T, Verhoogen R, Sercu M, et al. (2017) Not extent of telecommuting, but job characteristics as proximal predictors of work-related well-being. J Occup Environ Med 59: e180-e186.

- Eddleston KA, Mulki J (2017) Toward understanding remote workers’ management of work-family boundaries: The complexity of workplace embeddedness. Group & Organization Management 42: 346-387.

- Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Pastore M, et al. (2020) Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Front Psychol 11: 1713.

- Giménez-Nadal JI, Velilla J (2020) Home-based work, time endowments, and subjective well-being: Gender differences in the United Kingdom.

- Kim, YJ, Kang SW (2020) The quality of life, psychological health, and occupational calling of korean workers: Differences by the new classes of occupation emerging amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 5689.

- Bruno G, Panzeri A, Granziol, et al. (2021) The Italian COVID-19 psychological research consortium (IT C19PRC): General overview and replication of the UK study. J Clin Med 10: 52.

- Lyttelton T, Zang E, Musick K (2020) Gender differences in telecommuting and implications for inequality at home and work (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3645561). Social Science Research Network.

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther 33: 335-343.

- Zimet G, Dahlem N, Zimet S, et al. (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Assess 52: 30-41 .

- Pfefferbaum B, North Cs (2020) Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 383: 510-512.

- Lo Destro C, Gasparini C (2021) COVID-19 psychological impact during the Italian lockdown: A study on healthcare professional. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 1-16.

- Hayman J (2010) Flexible work schedules and employee well-being. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations.

- Manuel JI, Martinson ML, Bledsoe-Mansori SE, et al. (2012) The influence of stress and social support on depressive symptoms in mothers with young children. Social Science & Medicine 75: 2013-2020.

Corresponding Author

Gilberto Gigliotti, University G. D'Annunzio of Chieti-Pescara, Department of Neurosciences, Imaging and Clinical Sciences, Via dei Vestini, 31 66100 Chieti, Italy, Tel: +39-3927235943.

Copyright

© 2022 Gigliotti G, et al. This This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.