Impact of COVID-19 on Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) from March 2020 to February 2021 in Bronx, NY

Abstract

Introduction: Patients with serious mental illnesses (SMI) have higher rates of metabolic illnesses, cardiovascular and respiratory disease, as well as social deficiencies such as poor housing, and limited support systems. This makes them vulnerable to relapses, symptom exacerbations, and a wide range of negative health and psychosocial outcomes especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, having appropriate strategies to address their needs and adequate accessibility to mental and medical health care services, can decrease the rate of psychiatrically/psychological and medical decompensation and save their life. The outreach to the patient with SMI during the pandemic was very challenging. Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) is an evidenced-based practice that offers treatment, rehabilitation, and support services to individuals that have been diagnosed with SMI. The Covid-19 pandemic caused an increase in the difficulty of accessing to ACT services as well. The current study evaluates the impact of COVID-19 on ACT services from March 2020 to February 2021 in NYC. Our aim is to make recommendations that would develop some interventions and action plans to improve ACT services during crisis.

Method: This is a retrospective study on patients who are followed by Bronx ACT team affiliated with the Institute for Community Living (ICL) in NYC from March 2019 to February 2021. The study compared the number of hospitalizations and the number of visits in March 2019- February 2020 (pre-Covid-19 period) to March 2020- February 2021(Covid-19 period). Data analyzed with SPSS.

Result: 68 patients were included in the study. A total of 311 hospitalizations registered. 189 from March 2019 to February 2020 and 129 from March 2021 to February 2021 which shown statistically meaningful decrease (P-value 0.026). A total 7968 Visits registered. 4201, from March 2019 to February 2020, 100% in person visit and 3767 from March 2021 to February 2021, 51% tele-visit and 49% in person visits, Which is statistically not meaningful (PV > 0.05).

Discussion/Conclusion: Our study demonstrated that if essential services are defined and maintained while promoting staff resilience and wellness, along with giving psycho-education to patients and their family members, the rate of hospitalization in SMI patients during the Covid-19 pandemic can be reduced and these patients can remain healthy in the community. It's also important to reiterate that Tele-health played a critical role to provide ACT services while lowering the patients and the healthcare-providers' risk of Covid-19 infection.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is caused by the novel coronavirus (CoV), SARS-CoV-2, that predominantly affects the respiratory system. In addition to the physical impacts, COVID-19 can have serious effects on people's mental health [1]. There is increasing evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can be neuro-invasive, resulting in neuropsychiatric complication [2]. SARS-CoV utilizes two pathways to manifest itself in a neuropsychiatric form: Direct and indirect. The direct pathway is infection via hematogenous and neural pathways while the indirect way includes hypoxia, immune injury and hypercoagulability. These pathways can cause viral encephalopathy, infection, toxic encephalopathy and acute cerebrovascular disease. A wide range of psychological outcomes has been observed during the virus outbreak, at individual, community, national, and international levels. Specifically, at the individual level, people are also likely to experience fear of getting sick or dying, feeling helpless, and being stereotyped by others [3].

The prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression, because of the pandemic in the general population, are 29.6, 31.9 and 33.7% respectively. In the current crisis, it is vital to identify individuals prone to psychological disorders from different groups and at different layers of populations, so that with appropriate psychological strategies, techniques and interventions, the general population's mental health is preserved and improved [4]. Recent studies have revealed an association between medical history and increased anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 spread [5,6]. Previous researches had shown that medical history and chronic illnesses are associated with increased psychiatric distress levels [7]. People who have a history of medical problems and are suffering from poor health may feel more vulnerable to a new disease [8]. Suicidal ideation was elevated during the COVID-19 pandemic; approximately twice as many respondents reported serious consideration of suicide in the previous 30 days than did adults in the United States in 2018, referring to the previous 12 months (10.7% versus 4.3%) [9].

For such groups - including the elderly, the minorities, the severely mentally ill, those suffering from substance use disorders and the homeless, COVID-19 has also created significant barriers to access to health services, partially due to the disruption of services, an overwhelmed healthcare system and the pressure on medical professionals.

Assertive Community Treatment is an evidenced-based practice that offers treatment, rehabilitation, and support services, using a person-centered, recovery-based approach, to individuals that have been diagnosed with serious mental illness (SMI).

ACT is well-established and best-researched community, psychiatric model of care. There are three broad categories outlined high standards of care: 1) Human resources: structure and composition, including using team approach, having frequent team meetings, and small caseloads 2) Organizational boundaries, including taking responsibilities for crisis intervention, admission, discharge planning, and defining admission criteria, and 3) Nature of Services, including community-based engagement, assertive outreach, high frequency and intensity of services, etc. In short, successful community psychiatry's best-practices of care rely on essential services that involved regular, in-person support of patients in the community milieu. Outreach is one of the core components of the ACT service delivery models, and the other fidelity features facilitated this by mandating high provider-to-client ratios, interdisciplinary collaboration and flexible work schedules to allow patients' timely access to care [10,11].

The main goal of ACT services is to assist individuals to achieve their personally meaningful goals and life roles. ACT is to help people become independent and integrate into the community as they experience recovery. Secondary goals include reducing homelessness and unnecessary hospital stays. In this way, ACT offers treatment in the "real world" and the team of professionals provides help using a "whole team" approach ([12] OMH).

COVID -19 could affect patients with SMI who get ACT services in different way. It affects them not only same as general population but also because of disruption of ACT services and difficulty with outreach, possibility decreasing quality of care increasing rate of medication non-adherence, as well as overwhelming and burning out of the ACT providers.

Telemedicine has proved to be a safe and effective method of providing services to patients with psychiatric disorders - including evaluation, psychotherapy, medication management, case management, supportive counseling, and psychoeducation. However, implementation of telemedicine in the United State in the mental health field in general and particular in ACT program has its own limitations such as lack of access to phones and broadband WiFi and is yet to provide a substantial level of care [13,14].

Our current study evaluates the impact of COVID-19 on ACT services from March 2020 to February 2021 in NYC. Our aim is to make recommendations that would develop some interventions and action plans to improve ACT services during the crisis.

Methodology/Data Analysis and Evaluation Techniques

This is a retrospective study on patients who are followed by Bronx ACT team affiliated with the Institute for Community Living (ICL) in NYC from March 2019 to February 2021.

The Electronic Health Record (EHR) and data would be reviewed from March 2019 to February 2021 to collect number of visits, number of hospitalizations. Visits including tele-visits and in-person visits which were done by a multidisciplinary ACT team member.

Data from March 2019 to February 2020 considered as pre- Covid-19 and from March 2020- February 2021 Covid-19 and data compared in two duration of time.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects in this study are patients who get psychiatric services from the ICL-affiliated Bronx ACT team in the Bronx, NY.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who has documented central nervous system disease or those with clinically significant or unstable cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or hematologic conditions and admitted to the hospital (Admitted to the hospital with medical problem, non-psychiatric problem).

This was a retrospective study based on chart review so it does not pose any physical threat to the patients. No identifying data would be gathered to eliminate any risk of confidentiality breach. All data was encrypted and saved in password protected digital files.

There were no provisions for treatment of adverts effects.

This is a retrospective study and does not include any recruitment or compensation.

Using encrypted files and saving in password-protected files would ensure that data was stored safely and confidentially.

The data was analyzed with statistical software such as Excel and SPSS.

Result

68 patients were included in the study during the 2 years from March 2019 to February 2021. There were 19 females (28.3%) and 46 males (71.7%). Ages ranged from 20 to 77 with a mean of 49 and a standard deviation of 14.8 years.

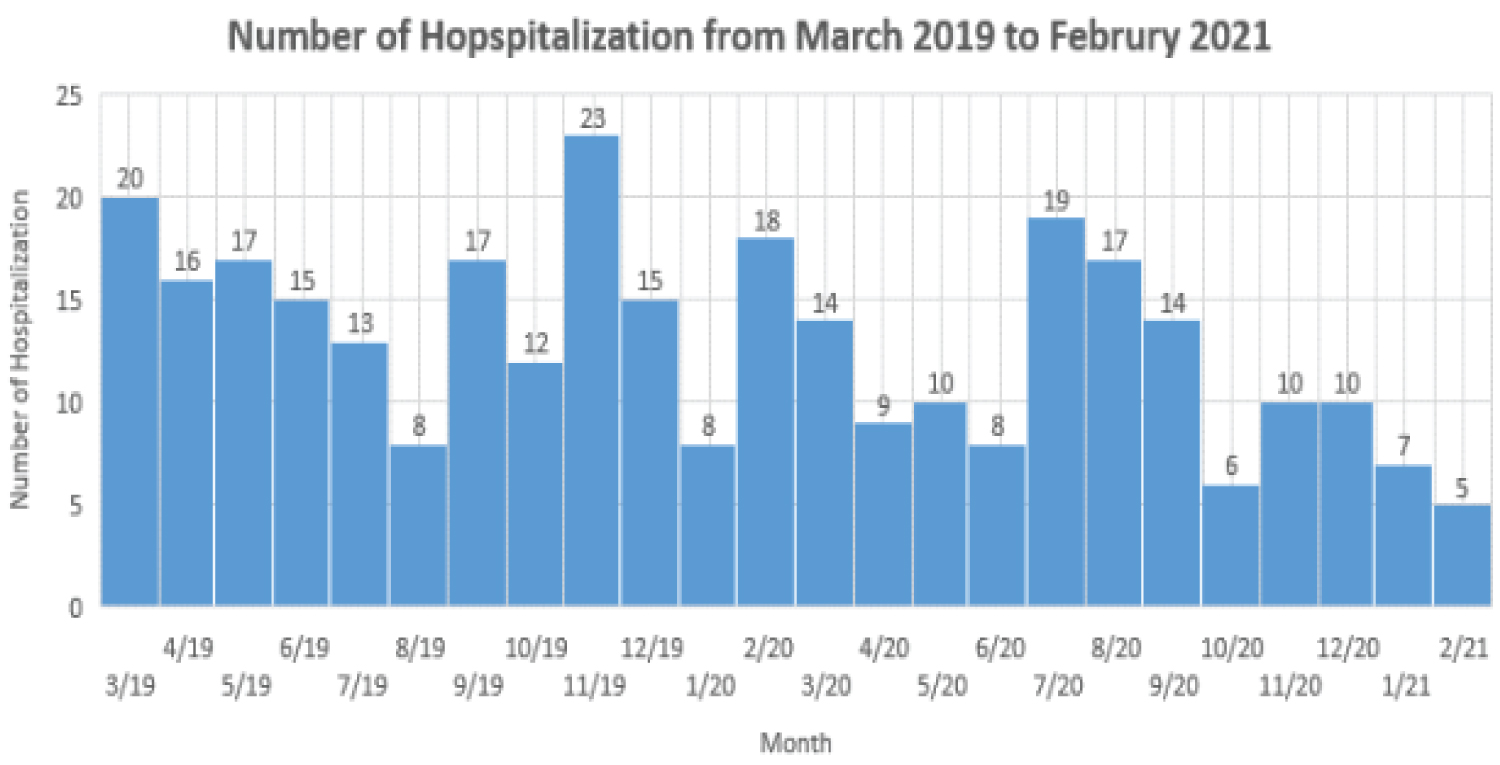

A total of 311 hospitalizations registered from March 2019 to February 2021, 189 from March 2019 to February 2020 and 129 from March 2021 to February 2021 which shown statistically meaningful decrease (P-value 0.026). Figure 1 shows hospitalization from March 2019 to February 2021 in different month.

A total 7968 Visits registered from March 2019 to February 2021. 4201 from March 2019 to February 2020 (mean = 350 + 39.3 Max = 431 Min = 270), 100% in person visit and 3767 from March 2021 to February 2021, (mean = 313 ± 61.5 Max = 385 Min = 219) 51% tele-visit and 49% physical visits, which is statistically not meaningful (P-value = 0.17). Figure 2 shown number of visits from March 2019 to February 2021 in different month.

Discussion/Conclusion

In the months following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, efforts to curb the spread of the virus have led to far-reaching socioeconomic upheavals and disruptions in the delivery of healthcare (World Health Organization [15], with unprecedented impact on the practice of community Psychiatry. Community psychiatry is often less prioritized in public health pandemic response planning, although it serves vulnerable populations, which are typically disproportionately impacted by disasters [16].

The definition of essential services in community psychiatry is not a clear one, and it relied on the best judgment in determining which services fall in this category, balancing guidelines from model fidelity literature, shifting availability of resources, and latest public health directives. Ethical principles including proportionality, minimizing harm, equity, and reciprocity also helped to guide these decisions [17].

The scale of the changes was large, and the pace of changes rapid, making it unfamiliar and challenging to the team. Gathering the different and often competing priorities presented by COVID-19, formulated the response strategies on three key principles: (i) Defining and maintaining essential services while limiting risk of contagion, include , protecting team capacity to preserve essential services, prioritizing and improving skills in contact risk assessments, adapting new communication media, creative solutions in keeping patient contact, harnessing community resources, developing new collaborations, on‑going focus on infection control, community testing and related advocacy. (ii) Promoting health and mitigating physical and mental health impacts on patients, such as systemically prioritizing the most vulnerable, addressing loss of community resources, patient support and group activities re‑imagined, on‑going psycho education on illness management and coping, maintaining preventative and medical legal measures, adapting Pharmacotherapy and (iii) Promoting staff resilience and wellness like, learning from experience and fostering staff resilience proactively, addressing staff morale and avoiding moral Injury, valuing responsive and responsible leadership [18].

We hypothesized that the COVID-19 pandemic would have a profound effect on patients who are followed by ACT teams due to the deceasing number of visits, and in-person visits, developing tele-visits, an increasing number of hospitalizations, lengthening admissions and finally an increasing number of suicide attempts and homicidal ideations.

The current study showed all our hypotheses to be wrong and hospital admissions decreased during the Covid-19 pandemic and the number of total visit decreased during this time in our patient. The following factors may apply: 1) ACT staff clearly understand that SMI patients are very vulnerable to decompensating, which led the staff to provide better quality of services to every individual 2) Tele visit became available which is more convenient for ACT team and help provide more services which may not be registered as a visit but help patient to not feel lonely and isolative which is very prominent during crisis, 3) Patients with ACT services developed a connection with the providers before the pandemic started, so limitations for tele-visit are less than other patients. 4) Patients stay at home more than before and they have been interacting less with society leaving less room for possible aggression in social situations, 5) Family members of the patients provided more support to the them helping stay psychiatrically stable.

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed a strong and unique challenge to particularly the nature of services involved in community psychiatry. The outreach-based practice was facing the potential compromise and developing virtual/ tele health outreach. Current study shows tele-visit helped to decrease the number of hospitalization during the Covid crisis in patients with ACT services. On the other hand, tele-visits can be more convenient for the team if the patient has access to a phone or other remote device to allow such visits.

The team need to identify what platforms were best suited to the wide variety of services that are provided, test those platforms, and implement appropriate and practical formats for encounters. These were stratified by services that have both audio and visual components as opposed to telephone contact only [19].

Tele-visits during the Covid pandemic play an important role in helping the patient to stay in the community and decreased the rate of hospitalization, so providing cell phones and devices to patient for tele visits is critical, and the ICL Bronx ACT strived to do just that. Educating health care workers for telemedicine and encouraging them to use it also can improve the quality of services.

In a study by Alavi, et al. they stated that during the pandemic all routine appointments were transferred to remote care, including medication reviews, post-hospital visits with established and stable patients, and medication refills. In person visits was limited to patients requiring injections, urgent psychiatric evaluations, or encounters regarding new and unstable conditions after hospitalization. Even for post-hospital encounters, were recommended first considering a tele health encounter with the patient in a clinic and the physician on camera from a different site. Most face-to-face appointments, including psychiatry, psychotherapy, home-based care, and autism services were modified to occur by phone or via a virtual platform, unless it was absolutely necessary to see the patient in-person [19].

If tele-visit is utilized in the ACT outreach program only after a certain number of in- person visits, the patient would be able to establish a personal connection with the providers thus allowing the providers to have an easier time finding an effective way to support patients to achieve ACT goals. With tele visit, providers spend less time on the way to reach out to the patient, so saving at least half an hour for every visit during the day, can save some hours in the month.

The team needs to evaluate patients during tele-visits to determine who needs in-person visits, injections or more frequent contact when in-person visits are limited for public health reasons.

As we know, there is always limitation for ACT services in every state. However, by cutting down commute times using tele-visit, ACT teams can take care of more patients and provide services to patients who have been on a waiting list and help them to be psychiatrically stable.

The COVID-19 pandemic and current study show that if Offices of Mental Health implement tele visits to the ACT team members under specific guideline and instruction, more SMI patients can get the help that they need.

The most important and interesting finding, in our study was that our patients did not do worse during the pandemic, That hospitalizations were down despite our fears that they would increase. We believe our data can be as the foundation for development of effective practices that predict susceptible populations and offer treatment and support services for these patients during emergencies such as pandemics.

References

- Huang Y, Zhao N (2020) Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 epidemic in China. A web-based cross sectional survey. Psychiatry Research 288: 112954.

- Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S (2020) Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric squeal of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun 87: 34-39.

- Hall RC, Hall RC, Chapman MJ (2008) The 1995 Kikwit Ebola outbreak: Lessons hospitals and Physicians can apply to future viral epidemics. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 30: 446-452.

- Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. (2020) Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta analysis. Globalization and Health.

- Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, et al. (2020) A Nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 3165.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. (2020) Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 1729.

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7: 547-560.

- Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, et al. (2018) Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder after critical illness: a UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care 22: 310.

- Results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health (2018) Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Bond GR, Salyers MP (2004) Prediction of outcome from the Dartmouth assertive community treatment fidelity scale. CNS Spectr 9: 937-942.

- Dieterich M, Irving CB, Bergman H, et al. (2017) Intensive case management for severe mental illness. Schizophr Bull 43: 698-700.

- Test MA, Stein LI (1980) Alternative to mental hospital treatment. I. Conceptual model, treatment Program, and clinical evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 37: 392-397.

- Egede LE, Ruggiero KJ, Frueh BC (2020) Ensuring mental health access for vulnerable populations in COVID era. J Psychiatr Res 129: 147-148.

- Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C, et al. (2021) The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Report - 117.

- Druss BG (2020) Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in populations with serious mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry 77: 891-892.

- Tauber AI (2002) Medicine, public health, and the ethics of rationing. Perspect Biol Med 45: 16-30.

- Kirwan IGN, Beder M, Levy M, et al. (2021) Adaptations and Innovations to Minimize Service Disruption for Patients with Severe Mental Illness during COVID-19: Perspectives and Reflections from an Assertive Community Psychiatry Program. Community Mental Health Journal 57: 10-17.

- Alavi Z, Haque R, Felzer-Kim IT, et al. (2020) Implementing COVID-19 Mitigation in the Community Mental Health. Community Ment Health J 57: 57-63.

Corresponding Author

Neda Motamedi, MD, Bronx Care Health System, psychiatry department, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Bronx, New York, USA.

Copyright

© 2022 Motamedi N, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.