General Medicine in the Time of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) and Beyond: Is it Falling Apart, Changing or Reinforcing? The Theory of the Braid Group

Abstract

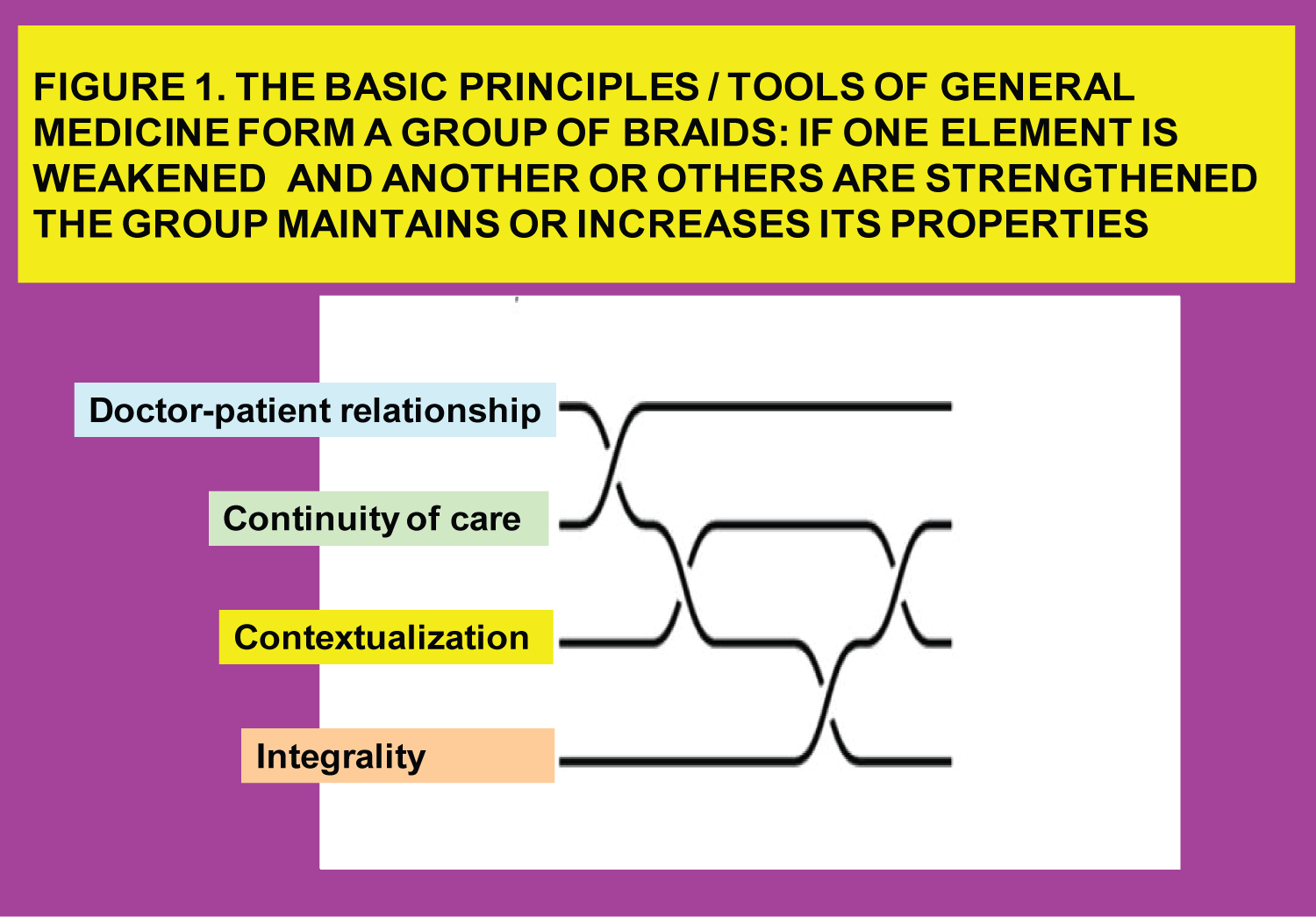

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has produced a dramatic change in the practice of general medicine (GM). Many of the aspects that were taken for granted in it have been profoundly altered. The most spectacular change has to do with telecare/telehealth: Remote consultations without the physical presence of the patient, which account for 80% of the total and which in all probability will be permanent. This situation affects the basic principles or tools of GM, especially the doctor-patient relationship that seems to disappear and consequently to crumble the practice. However, this article proposes another opposite view: The basic principles of GM - doctor-patient relationship, continuity of care, contextualization and comprehensiveness - are interwoven. In this way, even accepting the weakening of the doctor-patient relationship, the changes in the practice based on telecare may mean a reinforcement of the continuity of care, contextualization and comprehensiveness. What makes GM so effective and efficient is not the doctor-patient relationship in isolation, but the braiding of its set of basic principles/tools. Consequently, the braided group structure achieves a complex pattern that is greatly reinforced, achieving more strength, toughness and resistance to fatigue, suppressing cracks and supporting each other. Changes in the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 era will greatly strengthen GM.

Keywords

COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Telemedicine, Doctor patient relation, Continuity of care, Comprehensiveness, Contextualization, General practice, Framework

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has produced the biggest change in the organization of general practice for 200 years. The COVID-19 epidemic and the lockdown measures have significantly reduced the results of the follow-up, control, screening and vaccination indicators for patients in primary care [1]. Many of the aspects taken for granted in general medicine/family medicine (GM) has been profoundly altered. The coronavirus pandemic has caused a massive rewriting of the way healthcare is delivered [2].

The main modifications are related to social distancing and the most spectacular change has to do with telecare/telehealth or remote consultations without the physical presence of the patient, although other changes may be the use of masks, the limitation of the use of the waiting room and the presence of companions of the patients, the delay in consulting medical services for potentially serious health problems due to fear of COVID-19, etc. Telehealth is defined as the provision of health services through telecommunications technologies. The modalities include telephone, videoconferencing, health applications and programs through the Internet. Furthermore, telehealth interventions can be described as synchronous or asynchronous. Synchronous treatment is interactive communication that occurs in real time, such as by phone and video conference, and is the closest thing to face-to-face consultation. Asynchronous consultations include emails, text messages, faxes, applications, and online programs [3].

In many countries, face-to-face consultations have been reduced to approximately to 20% of their previous level, and most contacts are now provided remotely through consultations by telephone, electronic messaging, and more rarely video [2]. These changes will almost certainly be permanent by now; it will not return to the previous situation. There is no doubt that the expanded role of telehealth will continue even if COVID is no longer the threat. Telecare will likely get things done faster, more efficiently and more conveniently for patients and physicians alike. Obviously, remotely consultations will not be all visits, but it could be a large proportion of these and that can be an important element of risk for general medicine or, conversely, an opportunity to strengthen the primary care system [4,5].

For some general practitioners (GPs) this "new normal" of GM, where they stay away from patient consultations, without a genuine face-to-face doctor-patient encounter, does not make sense and generates suffering just thinking that the future clinical activity focuses more on the telephone keypad. This scenario seems to imply that the basic principles of GM as an academic discipline [6,7], which made it sustain itself, differentiate itself and maintain a specific status, are crumbling. How could we understand this fact that GM is experiencing a seismic shift? To understand it we have to review the four basic principles of GM/FM, which are the doctor-patient relationship, continuity of care, attention to context, and comprehensiveness.

Methods

The comments on this article should be considered as a personal point of view, based on the author's experience and the search and review of the literature using a non-systematic or opportunistic pragmatic approach, considering the bibliographic references of selected articles, book reviews related to the topic and Internet searches based on published studies on the topic.

Discussion

Doctor-patient relationship

The doctor-patient relationship is a complex phenomenon made up of several aspects, among which we can highlight doctor-patient communication, patient participation in decision-making and patient satisfaction. These characteristics have been associated with the communicative behavior of the physician and the autonomy of the patient in medical care [8-10].

While the doctor-patient relationship cannot be expressed in numbers or reflected in health statistics, there is overwhelming evidence that it plays a critical role in the health care process, and that it continues to largely determine the effectiveness of individual health care. Its usefulness to obtain better therapeutic results, its value in itself as a therapy, its value to obtain better data by obtaining more biopsychosocial information, more patient satisfaction), improvement in compliance, satisfaction and recall of the information given by the doctor, etc., have been reported [1-8,11,12].

For Balint, the drug most used in GM is the doctor himself; the interview itself is therapeutic. In his writings on "the doctor as drug" he establishes the fact that he himself as a drug should be dosed and is capable of producing intoxication like any drug. Relatively often, the relationship between doctor and patient is bad or strained; in these cases the "drug" does not achieve the expected results. This so-called "doctor" drug is powerful and can have many side effects. You have to know how to prescribing it. In any case, it is unanimously accepted that the chances of success in a treatment are directly proportional to the quality of the doctor-patient relationship [13,14].

Continuity of care

Continuity of care is other of the defining characteristics of GM [15-17]. It is at this level of health care that the opportunity to study the natural history of the disease is more easily presented to professional [18]. GP work includes the natural history of the health problems and the individual and family life cycle, and thus, it is in an optimal place to observe from the family history, the final consequences of any health problem. The most simple and useful way to achieve effective care is continuous care [19]. Continuity of care in GM - the long-term relationship established between the general practitioner and the patients in her office - has positive effects from a clinical and epidemiological point of view.

Continuity of care allows the physician to see repeated patterns of events and trends or regularities across generations, family functioning and its relationship to events, family structure, coalitions among members, family rules, myths, rituals, etc. The continuity of care in the sense that a patient repeatedly consults with a GP, forming a therapeutic relationship, has been described as an essential trait and a defining characteristic of GM. Although it can be seen from different perspectives, suggesting a hierarchy of dimensions from less to greater complexity, in any case the GPs offer continuity; that is, they offer the follow-up of specific health problems and the follow-up of the person with the set of health problems that will affect her throughout her life. The benefits of continuity are multiple, from the reduction of patient mortality to the reduction of the costs of the health system, including important opportunities for epidemiological knowledge of health problems. Continuity of care between doctor and patient builds trust and enables the doctor to use available time more productively. Overall, relationship continuity is highly valued by patients and clinicians, and evidence suggests that it leads to more satisfied patients and GPs, reduces costs, and achieves better health outcomes [20,21].

Contextualization

It must be remembered that individual disease depends on contexts and in turn produces consequences in the contexts: Social, cultural, economic, environmental and political where it takes place. Therefore, the clinical activity can always (must) have a community dimension, even when working with individuals or patients. The patients are in contexts (families, social groups, neighbourhoods) and immersed in social networks that involve: Resources, influences, connections. Contextualization is the GP's tool to implement family and community care with a biopsychosocial approach. At GM, individual, family and community care are elements of the same reality and cannot be separated. When we properly care for a person, we are doing individual, family and community care at the same time [22].

GPs do not treat illnesses, but they care for people in their contexts. So an important characteristic of GM is that the individual cannot be separated from her context. The diagnostic process is a mental operation by which the pathology is identified and the disease is evaluated in patient' context. The complexity of GM lies in the contextualization of medical care in each patient. The GP works in an environment in which there is a high prevalence of symptoms of discomfort, but a low prevalence of established disease and the disease episode is part of the entire patient' landscape [23-25].

Integrality

Integrality is other of the basic characteristics of GM. From the pedagogical point of view, some theoretical dimensions of Integrality can be described: 1.-Provision of integrated and accessible services (GPs are responsible for serving a large majority of personal care needs); 2.-Comprehensive health services (general practice services include promotion of health, prevention of morbidity, curative care and terminal care); 3.-Comprehensive care, which is to having a bio-psychosocial approach; 4.-Comprehensive understanding: Observer (the doctor) is an integral part of what he is observing, and GP must use data qualitative and quantitative; and 5.-Interactive Integrality: Reciprocal feedback and multiple perspectives. In GM, is needed to knowing that "dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants". [26].

In GM is conceiving the family/community as an integral system helps to understand individual symptoms that may play a role within the group dynamics. Thus, the persistence of symptoms in an individual may indicate a difficulty on the part of her system (the family, etc.) to adapt to a certain situation of change or to resolve a certain conflict. GP should use decentralized knowledge processes, without a single center, but that they are travelling from node to node. The GP should be a methodological opportunist in the sense that he is willing to go through various possible ways to achieve his goals in each particular situation [27].

Integrality in GM also means that GP is committed to the whole person and not to a set of knowledge, a group of diseases or a special technique in particular. That commitment extends in two ways: First, it is not limited by the type of health problems; the GP is available for any health problem in a person of any sex and age; its practice is not even limited to what is strictly defined as a health problem: the patient defines the problem. This means that a GP can never say, "I'm sorry, but your illness or illness is not in my field". Any health problem of patients is in GP work field; although the GP can refer the patient for specialized treatment, he/she is responsible for the initial assessment and coordination of care. The GP commitment with the patient does not have a defined end point; it does not end with the cure of a disease, the completion of a course of treatment, or the incurability of a disease; In many cases, the commitment is established while the person is healthy, before any problem has developed, that is, GM is defined in terms of relationships, which makes it unique in the main fields of clinical medicine [28].

The theory of the braid group

In reality, the doctor-patient relationship, continuity of care, contextualization and comprehensiveness are the GP's own tools for diagnosis and treatment. And these do not occur in isolation, but are linked to each other. This supposes an important reinforcement of the same. The basic principles/tools of GM form a "group of braids": If one element weakens and another or others become stronger, the group maintains or increases its properties (Figure 1).

A braid is a weaving that results from interlacing strands by alternately crossing them together and tightening them. A braid is a complex structure or pattern formed by weaving together two or more strands of flexible material. The structure is formed with each component strand which functionally zigzags forward through the overlapping mass of the other strands. In this way, interlacing can be compared to the weaving process, which generally involves two separate sets of yarns, the warp and the weft. Braids are a symbol of identity and resistance. A rope or fabric increases in resistance by braiding. Braiding creates a composite rope that is thicker and stronger than non-woven strands of yarn. Braided composites have superior toughness and fatigue resistance, as well as suppress crack production. Braids are often used figuratively to represent interwoven materials or combinations of materials [29,30].

General medicine in the times of COVID-19 and beyond

Is it possible to remain being GP when can't be physically present the patients? Can the computer screen, which has been criticized for decades, be used as a portal for connection? Can the connection and the doctor-patient relationship still happen? The COVID-19 experience is teaching us what is possible. GPs are facing a new type of connection/doctor-patient relationship, but also a new type of continuity of care, contextualization and comprehensiveness, with advantages and disadvantages [31].

For non-face-to-face consultations (by telecare: Telephone, etc.) to be useful for health outcomes, they must not destroy the value of the doctor-patient relationship (as a main diagnostic and therapeutic tool) However, it is true that in this telecare scenario it can suffer, weaken and change. Technology affects the user, be it the doctor or the patient.

The doctor-patient relationship model is a "context creator" element through the relationships and communications established with patients in face-to-face or remote consultation. "Context creation" is the result of implementing a series of doctor-patient relationship strategies to make services acceptable, relevant and accessible, in face-to-face or also in remote consultation. In this relationship model, the strategy cooperative-participatory-significant takes on special importance, where the relationship between doctor and patient is one of "sharing" and "helping", and implies a therapeutic relationship between doctor and patient, which can also be carried out through telecare. It is important to pay attention to the fact that this therapeutic context, also in remote consultations without face-to-face visit, can induce biomedical processes in the patient's brain that can improve or reduce the effects of the chosen interventions. Thus, the context works like a drug, with real and secondary effects, including nocebo-placebo effects, which also occurs in virtual consultations without the physical presence of the patient [32].

In any case, if the doctor-patient relationship changes or is limited by telecare, the key in GM for this basic tool to resist is to reinforce the other GM tools/principles in which it is woven or braided, in order to achieve sufficient strength. Doctor-patient relationship can be "lost" or changed in some or most of the remote consultations without face-to-face relationship; but that relationship, if it is already established, is maintained through continuity of care, contextualization and comprehensiveness.

In addition, the scenario that many consultations are through telecare or remote consultation, can contribute strengthening elements of the other basic principles/tools of GM. More flexibility in work patterns can be achieved by designing new consultation approaches to improve continuity of care; for example by ensuring that electronic messages and requests for phone calls are answered by the patient's GP whenever possible. Many GPs find remote consultation with patients they know easier, and patient satisfaction is significantly better when GPs have responsibility for a defined list of patients. Fewer face-to-face contacts can allow for longer consultations to be standardized that are more patient-centered and less stressful for clinicians. The COVID-19 crisis provides an opportunity to make general practice more personal and contextualized [2].

Until now, all the proven techniques to establish a good relationship with patients involved physical proximity. This has changed. But there are advantages to video visits. The elderly patient who is unsteady can now be asked to show GP the layout of his house to identify possible risks of falls on the camera. If a patient cannot remember the name of a prescription that needs to be repeated, he or she may be asked to go to the medicine cabinet to retrieve the bottle. Other family members can be seen, and even animal petd who have kept the patient sane during the lockout. For patients without a car who would otherwise have to pay for a taxi or take risky public transportation, these types of visits make perfect sense if they don't need a full physical exam or lab tests. It is possible to create and strengthen healing relationships in telehealth encounters, based on what can be called "physical distancing with social connection" [33]. In any case, it should be taken into account that the doctor-patient care relationship is a technical instrument at the service of the diagnosis and treatment of the patient and that the doctor-patient relationship can take many valid forms, including the one that can be formed through telecare [34-36].

The changes that COVID-19 has forced can be a great opportunity for a greater implementation of non-face-to-face consultations, especially in the follow-up and control of patients with chronic diseases. Telemedicine can allow shorter and more frequent virtual visits for chronic patients, and it can added the ability to connect multiple providers in caring for a patient [37]. This new form of communication has been very well accepted by patients, and at the same time it serves to ask many of them about other associated pathologies for which they are under treatment, achieving comprehensiveness and contextualization more easily than in face-to-face consultations. Also it enables reminders regarding adherence to their treatments and improving compliance. It can allow more easily the assessment of control objectives and current clinical situation. In addition, the possibility of non-face care sometimes represents an added advantage related to avoiding the need for family members or companions to request permits to leave their jobs for a few hours, and this also represents a social or labor advantage.

Telecare consultations increase efficiency and are especially useful for patients with a problem "simple" or request to consulting it without spending time in our waiting room, which is often the case for young patients and adult professionals with difficulty disposing of time for face-to-face visits, which may include not only travel time, but also waiting time to access the GP. Telecare can on the other hand reduce 30% in the "bureaucracy" of face-to-face consultation. But, in any case, it is necessary to define with more evidence those specific clinical scenarios and situations in which remote care can and perhaps should be carried out. At the very least, special care must be taken to avoid delays for critical conditions such as early cancer diagnosis, acute heart disease, and pain. Probably, the first visits and the visits that are repeated several times for the same problem that is not well understood by the doctor, would be two situations that would require face-to-face visits. Older patients may have more difficulties than younger ones, and these can easier to have the perception of being 'abandoned', and more not indicated drug prescriptions, including antibiotics, can be made [38-41].

It is possible that useless visits can be stopped with the telecare. Keep in mind that many of the clinical examinations that the GP does are normal or confirm what she already suspects from the history. It is very important to remember that 80% of the diagnosis is made by the clinical interview, 10% by the examination and 10% by complementary tests [42]. But sometimes an unexpected finding can come up. For example, when the chest exam that was expected to be normal reveals pneumonia, or when rapid atrial fibrillation is detected in the patient who feels a little tired [43]. That is, an advanced clinical guideline will be required to assess which services can be delivered safely and effectively through telehealth and which cannot. But, in general, again, the Braid Goups Theory is helpful: The continuity of care, context and comprehensiveness data allow the GP to recognize when an alarm "red flag" appears during a remote consultation.

Non-medical -contextual- factors (factors that are related to the patient, the family, the doctor himself, the interaction between the doctor and the patients, demographic considerations, etc.) have more impact on the doctor's decision-making process in telemedicine. In other words: Telemedicine strengthens and favors contextualization. In view of the fact that in telemedicine, the doctor does not have the standard "medical" measures to examine the patient, the "extra (non) medical" or "non-biomedical" factors (contextualization) can gain a lot of weight in this scenario for diagnosis and treatment. Difficulties in evaluating the patient's situation from a distance make the diagnosis based mainly on indirect reports from family members, or from parents in the case of children, or from the caregiver in an elderly person, and not only or not so much from the patient himself. This fact explains the importance of shared decision-making in this telemedicine environment. These non-biomedical factors (contextualization) allow GPs to use a holistic or comprehensive approach, in which patients are viewed as a whole, and their individual capabilities and preferences are also considered [44]. In short, telemedicine can reinforce contextualization and comprehensiveness.

Likewise, the new telecare scenario, paradoxically, can be an opportunity for the GP to act as a more humane doctor: This ideally implies less acting and more authenticity. The lack of physical proximity of telemedicine makes certain unaccustomed informalities (in greeting, farewell, conversation) seem less incongruous with the doctor-patient relationship. The doctor and the patient are sharing a historical experience, and in this way they are no longer strangers. Clinicians often equate professionalism with a kind of formal role-play and fear deviations from this attitude [45]. Telemedicine is an opportunity for the doctor to be more of a person and less of a hierarchical superior of the patient; it is a opportunity to make general practice on a human scale [46]. On the other hand, it is evident that in the telecare setting, the clinical interview will emphasize more the aspects of attentive listening (by phone, for example): Listening carefully and communicating as equals in conversations that respect the knowledge and experience of both parties [47,48].

Conclusion

Now is the time to strengthen to the GP, which includes recreating and reinventing it, but also building on a solid previous foundation. I mean, the MG and the GP have changed ... but they also haven't changed! Or put another way, they have been strengthened. Although the basic principles/tools of MG have changed, their braided structure allows the academic discipline to be reinforced. The same previous basic tools can be presented to the patient and the GP "in another way", but they are the same, and they reinforce and sustain each other because these basic principles and fundamental tools are interwoven; they are, braided (Figure 1). Although the COVID-19 crisis and the post-COVID-19 period will probably weaken or change the doctor-patient relationship, the telecare will make that the continuity of care is maintained or strengthened, and contextualization and comprehensiveness may be reinforced; so, in this way finally strengthens the GM. What makes GM so effective and efficient is not the doctor-patient relationship in isolation, but the braiding of its set of basic principles/tools. A majority distance consulting model does not put the GP at risk of losing their skills. Converting in-person visits to telemedicine is a possibility that can be exploited by GPs and patients.

References

- Coma E, Mora N, Méndez L, et al. (2020) Primary care in the time of COVID-19: Monitoring the effect of the pandemic and the lockdown measures on 34 quality of care indicators calculated for 288 primary care practices covering about 6 million people in Catalonia. BMC Family Practise 21: 208.

- Gray DP, Freeman G, Johns C, et al. (2020) Covid 19: A fork in the road for general practice. BMJ 370: 3709.

- Reay RE, Looi JC, Keightley P (2020) Telehealth mental health services during COVID-19: Summary of evidence and clinical practice. Australas Psychiatry 28: 514-516.

- Frieden RT (2020) Will primary care physicians be COVID-19's next victims? Medscape.

- Looi MK, Coombes R (2020) Risky business: Lessons from covid-19. BMJ 369: 2221.

- Turabian JL (2017) Fables of family medicine: A collection of fables that teach the principles of family medicine. SM Journal of Family Medicine.

- Turabian JL (2017) A short collection of fables for learning the fundamental principles of family medicine: Chapter 1. Comprehensiveness, continuity, contextualization and family. Arch Fam Med Gen Pract 1: 32-39.

- Turabian JL (2019) Doctor-patient relationships: A puzzle of fragmented knowledge. J Family Med Prim Care 3: 128.

- Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JEJr (1989) Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care 27: S110-S127.

- Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD (2002) Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: A systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract 15: 25-38.

- Turabian JL (2019) Doctor-patient relationship in general medicine has a diagnostic meaning. Int Res Med Health Sci 2: 20-27.

- Turabian JL (2019) Psychology of doctor-patient relationship in general medicine. Arch Community Med Public Health 5: 62-68.

- Balint M, Hunt J, Joyce D, et al. (1984) Treatment or diagnosis. A study of repeat prescriptions in general practice.

- Turabian JL, Pérez FB (2010) The concept of treatment in familiy medicine: A contextualised and contextual map of a city hardly seen. Aten Primaria 42: 253-254.

- White ES, Gray DP, Langley P, et al. (2016) Fifty years of longitudinal continuity in general practice: A retrospective observational study. Fam Pract 33: 148-153.

- Beaulieu MD (2013) Teaching the essence of family medicine. Can Fam Physician 59: 1017.

- Hill AP, Freeman GK (2011) Continuity of care. Promoting continuity of care in general practice. Rcgp policy paper. The Royal College of General Practitioners.

- Morrell D (1991) The art of general practice. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Stott NCH (1983) Primary health care. Bridging the gap between theory and practice. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Richards H (2009) We must defend personal continuity in primary care. BMJ 339: b3923

- Turabian JL (2020) Epidemiological value of continuity of care in general medicine (part one of two). Epidemol Int J 4: 000135.

- Turabian JL, Pérez FB (2008) Individual health care with community orientation-contextualized attention: The figure is the background. Revista Clínica Electrónica en Atención Primaria 16: 1-5.

- Turabian JL (2017) For decision-making in family medicine context is the final arbiter. J Gen Pract 5: e117.

- Heath I, Evans P, Van WC (2000) The specialist of the discipline of general practice. BMJ 320: 326-327.

- McWhinney IR (1996) The importante of being different. Br J Gen Pract 46: 433-436.

- Turabian JL (2018) Concept of integrality in general medicine. Arch Fam Med Gen Pract 3: 54-57.

- Turabian JL (2017) Stories notebook about the fundamental concepts in family medicine: Comprehensiveness and integrality, the fable of the tree and the grass. J Gen Pract 5: 284.

- Turabian JL, Perez FB (2001) Community activities in family medicine and primary care. Díaz de Santos. Madrid.

- (2020) Braid.

- Carey JP (2017) Handbook of advances in braided composite materials: Theory, production, testing and applications. Woodhead Publishing, Duxford, UK.

- Hata SR (2020) The ritual of the table. N Engl J Med 383: 1301-1303.

- Turabian JL (2018) Doctor-patient relationship in pharmacological treatment: Discontinuation and adherence. COJ Rev & Res 1: 000521.

- Lin K (2020) Telemedicine tales: Let's reschedule when you're not shopping. Medscape.

- Turabian JL (2018) Doctor-patient relationship as dancing a dance. Journal of Family Medicine 1: 1-6.

- Turabian JL (2018) Pharmacological non-prescription, doctor-patient relationship and biopsychosocial approach: Foreign lands or foreign travelers? Archives of Community and Family Medicine 1: 39-42.

- Turabian JL (2018) The enormous potential of the doctor-patient relationship. Trends Gen Pract 1: 1-2.

- Kichloo A, Albosta M, Dettloff K, et al. (2020) Telemedicine, the current covid-19 pandemic and the future: A narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Fam Med Community Health 8: e000530.

- Godley B, Mackey RC (2020) COVID-19 spawns an important new MD job title. Medscape.

- Pallarés CV, Górriz ZC, Llisterri CJL, et al. (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic: An opportunity to change the way we care for our patients. Semergen 46: 3-5.

- Bingham JM, Black M, Anderson EJ, et al. (2020) Impact of telehealth interventions on medication adherence for patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and/or dyslipidemia: A systematic review. Ann Pharmacother.

- Turabian JL (2020) Acute respiratory infections in children during coronavirus disease 2019: Without reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction test and with risk of over-prescription of antibiotics, the perfect storm. Pediatric Infect Dis 5: 1

- Hampton JR, Harrison MJ, Mitchell JR, et al. (1975) Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigation to diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. Br Med J 2: 486-489.

- Salisbury H (2020) Teleconsultations for all. BMJ 370: m3211.

- Haimi M, Brammli GS, Waisman Y, et al. (2020) The role of non-medical factors in physicians’ decision-making process in a pediatric telemedicine service. Health Informatics J 26: 1152-1176.

- Kahn MW (2020) Pandemic and persona. N Engl J Med 383: e1.

- Turabian JL (2003) A medicine on a human scale. JANO 65: 10.

- Boström E, Ali L, Fors A, et al. (2020) Registered nurses’ experiences of communication with patients when practising person-centred care over the phone: A qualitative interview study. BMC Nursing 19.

- Hollander JE, Sites FD (2020) The transition from reimagining to recreating health care is now. N Engl J Med.

Corresponding Author

Jose Luis Turabian, Specialist in Family and Community Medicine, Health Center Santa Maria de Benquerencia, Regional Health Service of Castilla la Mancha (SESCAM), Toledo, Spain

Copyright

© 2020 Turabian JL. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.