The Lived Experience of African American Women with Lymphedema

Abstract

Background

African American women have a greater number of aggressive cancer treatments and higher incidence of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema (BCRLE) than Caucasians. BCRLE cannot be cured and the treatment requires patients to make considerable lifestyle changes and maintain daily and lifelong care to decrease the swelling and prevent exacerbations. Breast cancer survivors (BCS) with BCRLE have higher levels of anxiety and depression, more substantial financial burden as well as greater difficulty in maintaining relationships than those without this condition. Research has used BCRLE samples comprised almost exclusively of married and well-educated Caucasian women. Few studies have included sizeable numbers of African American breast cancer survivors. Consequently, little is known about the experiences of BCRLE from the perspective of African American (AA) women.

Objectives

This article describes perceptions of African American women's experiences in living with BCRLE including physical changes, functionality, perception of body image, family and social roles, coping techniques, and patient-healthcare provider relations.

Methods

A descriptive, phenomenological, qualitative methodology was used to interview 11 women.

Findings

Themes included: (1) Living with Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema caused a private condition to become public, (2) Enduring the Unexpected (3) Diminished Perceptions of Self Image, (4) Feeling Triumphant: God, church, family, friends, and significant others were acknowledged as key support systems, and (5) Distrust of physicians and other healthcare providers.

Keywords

African american, Breast cancer survivors, Breast cancer-related lymphedema

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer among African American women [1,2]. More than one in five women who survive breast cancer will develop arm lymphedema [3]. More than 2.4 million breast cancer survivors (BCS) are at risk for or are living with post-treatment breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRLE) [4,5] an accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the interstitial tissue that causes swelling, most often in the arm(s), and occasionally in the chest [6]. In the U.S. this translates into hundreds of thousands of women living with complications of such as, premature morbidity and negative quality of life resulting from breast cancer treatment (QOL) [7] are African American women [8,9].

A review of the research literature concerning African American women and BCRLE revealed a paucity of findings. Very little published data was found on the effectiveness of follow-up care in preventing, managing, or improving long-term effects of BCRLE and its treatment. Previous research has identified instances where African American women may experience inferior quality of breast cancer treatment and poorer outcomes as compared to Caucasian women [8]. What has been determined is that breast cancer survivors with BCRLE have higher levels of anxiety and depression, more substantial financial burden [10], as well as greater difficulty in maintaining relationships than those without this condition [5].

Research has used BCRLE samples comprised almost exclusively of married and well-educated Caucasian women. Some prime findings have determined that Caucasian BCS were found to express their emotions, practiced problem solving, and used escapism and tended to frequently attend formal support groups to cope with BCRLE [11,12]. Caucasian BCS experience less aggressive forms of breast cancer primarily due to comprehensive insurance coverage, early detection and mass mammography screening and state of the art follow-up treatment [13,14]. Finally, advanced disease, more radical treatments including more extensive surgeries and higher levels of obesity have all been linked to an increased risk for BCRLE. All of these characteristics are less reported in Caucasian patient populations [15].

Few studies [16-19] have used sizeable numbers of African American breast cancer survivors. No studies have been found that explicitly investigated the phenomenon of the experience of African American women who have acquired BCRLE. Those that included African American women in the sample have not focused on any potential differences by race. This descriptive, qualitative, phenomenological inquiry was conducted to enhance understanding of African American women's experiences in living with BCRLE. The findings from this study may be used to help healthcare providers examine the long-term psychological and psychosocial effects of BCRLE on the survivorship of African American women.

Methods

Following approval from the institutional review board of a large urban University, the recruitment and selection process primarily consisted of referrals from the primary healthcare providers in a large, urban cancer treatment facility. Criteria for inclusion in the study required that participants be (a) Be self-identified as African American women, (b) Able to speak, read, and write English, (c) Between the ages of 18 and 89 years old, (d) Self-reported or diagnosed with BCRLE prior to enrolling in the study, (e) Cognitively intact, and (f) Completed axillary dissection and/or sentinel lymph node dissection at least six months prior to being enrolled in the study. Referrals of participants where be made by a nurse practitioner (certified as a lymphedema specialist), a physical therapist (certified/specialized in lymphedema), and other healthcare professionals.

Maximum variation sampling was used to allow exploration of common and unique expressions related to BCRLE across a broad range of demographically varied cases [20]. Some of the variations included experiences associated with the development of BCRLE such as symptoms, comorbidities, and obesity/body mass index. Open-ended interviews allowed particular issues of interest to be discussed and permitted each participant to take the discussion in directions that reflected her own experience.

Two face-to-face, audio-taped interviews were completed with each participant. A mutually agreeable time and place was established for the interviews. Most interviews were held...? The initial interviews lasted from approximately 45 to 60 minutes and the second interview lasted from about 20 to 30 minutes. In order to describe the participants, data collection instruments used in this study included: Demographic, Medial History and BCRLE Symptoms List Self Report Form, and Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema Interview Guide [21]. All interviews were audio taped and conducted by the principal investigator. A numerical code was used to identify participants and their data.

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using thematic analysis. Data analysis occurred concurrently with data collection. Each interview was transcribed into a computer file and printed to provide a paper record. The paper copy was compared with the audiotape for accuracy. Analytic memos from notes taken during and after interviews were reviewed in combination with the transcripts. Verbal and non-verbal notes from the analytic memos were placed in chronological order and inserted, as notes into the transcripts.

Open coding was used to identify themes emerging from the interviews [22]. Categories were then identified and grouped. The goal was to create descriptive categories that linked underlying meanings together to form a preliminary framework for analysis. Words, phrases, or events that appeared to be similar were grouped into the same category. These categories were gradually modified or replaced during the subsequent stages of analysis that followed. The unit of analysis was the reviewed line by line text of each of the individual interviews. The next stage of analysis, axial coding, and involved re-examination of the categories identified to determine how they were linked [22]. Data were coded and listed according to the topical areas suggested by the interview guide research question.

Findings

The sample consisted of eleven African American women whose ages ranged from 50 to 73 years (M = 62, SD = 6.65) (n = 11; see Table 1 and Table 2). Characteristics of the lived experience as expressed by the research participants, included issues described in living with BCRLE symptoms such as physical changes, functioning, body image, coping mechanisms, family and social roles, and patient- healthcare provider relations. A total of twenty interviews were conducted in the participant's homes, one interview took place at the participant's place of business and one interview was held in a physical therapy department.

Three participants were between 50 and 60 years old, seven participants were between the ages of 61 and 70 years old, and one participant was between 70 and 80 years old. The educational background of the participants included four high school graduates; two participants had some college preparation; and five participants reported having a college degree. Over half of the participants were employed. One participant owned her own business. One participant worked part-time; four participants worked full-time; two participants were retired; and three participants were unemployed (n = 11; see Table 1).

Nine participants had BCRLE beyond Stage 0. Six participants reported stage 3 or stage 4. All participants had undergone an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND); three participants had a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB); another three participants reported having had a combination of both an ALND and a SLNB. Three participants had radiation therapy and six participants had a combination of radiation and chemotherapy and one participant did not have radiation or chemotherapy (see Table 2).

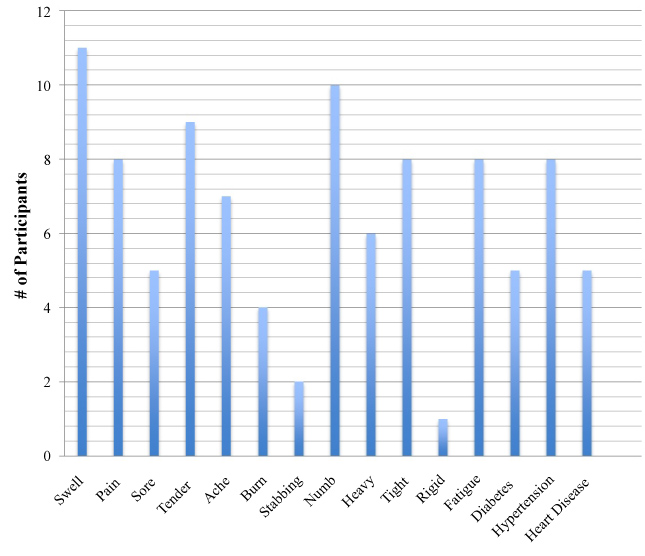

Participants had lived with BCRLE from 1 to 26 years. It has been suggested that preexisting co-morbid conditions of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease may influence the development of BCRLE [5]. The average height was 5'3'' (64.95 inches). The average weight was 192.3 lbs. A BMI over 25 indicates being overweight and 90.9% of the participants were considered overweight (BMI > 25). An adult who has a BMI of 30 or higher is considered obese (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012) [23]. In this study all of the participants, except one, had a BMI over 25 and eight participants were obese (see Table 3). African American women have the highest rates of hypertension (HTN) and diabetes (DM) which places them at greatest risk for unfavorable outcomes associated with BCRLE. However, in this study participants who reported greater numbers of preexisting co-morbid diagnoses did not consistently report more symptoms. Although ninety percent of the participants had a BMI over 25; being overweight and having BCRLE for longer periods of time were not related to more symptoms (see Figure 1).

Findings from interview data

Five themes were derived from the women's experiences in living with BCRLE. The first theme, Living with Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema, was identified from the participants' descriptions of what it was like to live with breast cancer-related lymphedema and whether the participants hid or shared their feelings with others. The participants' responses suggested that since breast cancer was a personal concern, the visible, physical symptoms of BCRLE caused a private health condition to become public and caused embarrassment. The visibility of BCRLE made having an illness harder to conceal. Thus, BCRLE made a private condition more apparent: "Sometimes your personal health is your personal business and nobody else's". By withholding their feelings about BCRLE and maintaining privacy these women perpetuated a sense of social isolation. Expressed views of BCRLE being a private/personal experience and why these concerns were not discussed with other people are further indicated in the following statements: "...once you get lymphedema it becomes public. ... it's a personal thing... I don't discuss it with my family... Not even all of my friends... it's just something that you don't tell everyone..."

Views regarding concerns/feelings about living with BCRLE were varied. Most of the participants in this study reported concealing their feelings about breast cancer and BCRLE for several reasons such as depression, fear of rejection, lack of knowledge, avoidance of confrontation with others, and resentment. Unfortunately, participants' level of comfort in being able to choose whether to discuss concerns about their breast cancer was altered with the onset of BCRLE. Participants' descriptions suggested a belief that their prerogative to decide with whom to disclose feelings represented a source of empowerment. This perception of power over a situation in which they perceived to have little to no control was seriously threatened with the onset of BCRLE. Women used terms such as "privacy" and "personal" to describe how they felt about having BCRLE.

The second theme, Enduring the Unexpected, emerged from participants' beliefs about the symptoms they had and how these tenacious and unpredictable symptoms affected their level of functioning in everyday life: "I'm having this thing the rest of my life... It's been 26 years with lymphedema...; "I think the most distressing thing about the lymphedema is that you never know when it's (BCRLE) going to come back... You can be symptom free for weeks at a time... but despite your best efforts, it will come back...".

Responses from the participants suggested that the two primary areas impacted by BCRLE in performing activities of daily living (ADLs) were discomfort from symptoms and impairments in function. The following responses are examples of how symptoms such as pain, swelling and weakness interfered with the performing ADLs: "...some pain, some discomfort and swelling is always there... If I move too quickly, or attempt to carry something, that sometimes is a problem... I noticed I have a deficit of strength... in that arm..." Another participant remarked: "I have to realize that I can't carry the grocery bag in my left hand and need to switch... if I drop a coin on the floor it's hard for me to pick it up because of the numbness...".

The third theme, Diminished Perceptions of Self Image, emerged from the participants' perceptions and beliefs regarding changes in how each participant saw herself as a woman after acquiring BCRLE: "it kinda of uh attacked my self-image". The majority of the women in this study reported that the physical changes caused by BCRLE negatively affected how they perceived their bodies. The overarching theme relevant to the physical changes had remarkable influence on body/self-image which represented more than physical appearance and/or sex appeal: "Yes it does change your body image because your body has changed... I see this as another challenge...because I'm still here... It is important to take time out for yourself..."; "I lost some of my independence...."; "... once you get lymphedema it becomes public. That was one of the reasons I was so afraid of getting it (BCRLE) because its noticeable...when you look at someone with that (BCRLE) you know they have had cancer I was really worried about that..."; "... I don't feel adequate or attractive because of the arm swelling... you want to have the arm look slim... I'm not a small woman but my arms are supposed to be smaller... that annoys me that I have to buy that larger top/extra-extra-large sometimes... "; "...I don't go anywhere, I don't want to be bothered with nobody. I rather stay in my room in the bed...."

Participants expressed how they didn't feel the same and how BCRLE imposed changes in attire and perceptions of physical attractiveness. Expressed views regarding body image suggested that the effects of BCRLE had monumental psychological effects on how women perceived the physical changes in their bodies. Their concerns exceeded outer appearance or sex appeal and went deeper altering psychosocial functioning. Their responses suggested that women living with BCRLE had to make a number of permanent adjustments in their lives which caused varied degrees of decreased self-esteem and social isolation.

The fourth theme, Feeling Triumphant, emerged from how the participants coped with BCRLE: "My support comes from God...and my family". God, church, family, friends and significant others were acknowledged as key support systems. These factors were prevalent influences in overcoming feelings of helplessness and hopelessness as reflected in the following comments: "My thing is I couldn't have fear and faith at the same time ..."; When I was diagnosed with this, I just ask the Lord I said, "Lord I know your will is going to be done. Help me to accept your will and help me to accept it with grace so I can be grateful"; "my support is my family and my friends..."

The majority of participants reported that they had no involvement with community support groups. Participants expressed diverse sentiments when describing why they had not support group involvement including disinterest, lack of knowledge, and/or motivation. God, family and friends were persistently acknowledged as the prominent factors that helped women cope with BCRLE. Participants reported having positive and unconditional relationships with their family members and friends for which they expressed feelings of gratitude. Faith-based cancer support groups have been recognized as more culturally appropriate and practical resources for African American women who tend to rely on family members, friends, ministers, and church members to assist with coping [24]. Women who had been involved in church-based groups agreed with this viewpoint.

The fifth theme, Distrust of physicians and other healthcare providers, was identified by participants' perceptions of how they were treated by healthcare professionals and what they had to say in response to that treatment: The women expressed frustration with their healthcare providers, "Just listen to us..." One participant said, "They just wanted me to know, go home take whatever therapy they had to offer, check for swelling myself...they seem to give me the impression that they expected me as an African American woman to handle and cope with it myself... I think there might be a perception in the greater healthcare industry that an African American woman will look after herself".

Responses from participants supported the assertion that a lack of information about breast cancer-related lymphedema before diagnosis commonly led to a perception that healthcare providers and especially physicians did not care about them as individuals. Most participants' responses indicated that between the time of their surgery and the initial discovery of symptoms of BCRLE they received no information regarding this condition.

To varying degrees participants reported healthcare providers were unconcerned and/or uniformed about BCRLE: "I got no information about lymphedema before my surgery... seems like the medical people should be able to give me some better answers than what they been telling me". Another participant shared a lack of concern by her provider: "... when I first told my doctor about the swelling, he said don't worry about that (arm swelling). The swelling will go down and I would be ok. But it just seems to come back on its own about a year later". Limited time with the provider contributed to participants' frustration: "... he wanted to only give me 5 minutes...he wasn't any help, I didn't go back to him..." Those perceived behaviors caused distrust and amplified perceptions of feelings of rejection, unconcern, uncompassionate and unsupportive attitudes on the part of some healthcare providers.

The emotions of the participants in this study varied and in most instances nurses and physical therapist were perceived to have shown more care and concern as compared to physicians who were generally considered less concerned. Descriptions of feelings of rejection, unconcern, uncompassionate, disrespectful, and no supportive attitudes by some healthcare providers were identified as contributing factors to participants' feelings of distrust. Among African Americans distrust of physicians has been attributed to the lack of interpersonal and technical competence, perceived quest for profit and expectations of racism during routine provision of healthcare [25].

Five themes emerged from participants' descriptions of perceptions and behaviors pertaining to the lived experience in living with breast cancer-related lymphedema. The first theme was identified from the participants' descriptions of what it was like to live with breast cancer-related lymphedema and whether or not the participants hid or shared their feelings with others: Living with Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema: "Sometimes your personal health is your personal business and nobody else's". The second theme emerged from participants' beliefs about the BCRLE symptoms they had and how these tenacious and unpredictable symptoms affected their level of functioning in everyday life: Enduring the Unexpected: "I'm having this thing the rest of my life!" The third theme emerged from the participants' perceptions and beliefs regarding changes in how they saw themselves as a woman after acquiring BCRLE. The physical changes caused by breast cancer-related lymphedema represented perceptions of dissatisfaction with body image. Participants acknowledged their bodies had changed and would never be like it was before. The overreaching theme relevant to the physical changes had remarkable influence on body-image which represented more than physical appearance and/or sex appeal. The fourth theme emerged from the participants' responses to the question of how they coped with breast cancer-related lymphedema. Participants expressed feelings of triumphant over BCRLE: Feeling Triumphant: "My support comes from God ...and my family". The fifth theme, Distrust of physicians and other healthcare providers: "There is no one black woman". "Just listen to us..." was identified by participants' perceptions of how they were treated by healthcare professionals and what they had to say in response to that treatment.

Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore African American women's experiences in living with breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRLE) including physical changes, functionality and perception of body image, family and social roles, coping techniques, and patient-healthcare provider relations. Data from this study contribute to the existing gap in nursing knowledge by assisting the profession to achieve a culturally-specific understanding of the influence of BCRLE on the lives of African American women. Findings suggest that BCRLE is a tenacious, unpredictable and recurrent condition which impacts the daily emotional and physical functioning, and perception of self-image in African American women with BCRLE. God and faith, and family are key support systems used by African American women to cope with BCRLE. All these factors support the necessity for culturally sensitive and compassionate care to African American women with BCRLE by healthcare professionals which is especially critical yet missing.

This research provides an unprecedented foundation for better understanding factors that influence perceptions in this patient population. Findings support the assertion that a holistic and culturally relevant approach is needed to adequately assess the perceptions of African American women in the following areas: (a) How the lack of knowledge regarding the consequences of BCRLE influence African American women's perceptions in living with BCRLE, (b) How the effects of the tenacious, unpredictable and recurrent symptoms of BCRLE impact daily functioning in African American women with BCRLE, (c) The influence of BCRLE on African American women's perception of their self-image, (d) The importance of faith and family as key support systems used in the coping by African American women with BCRLE, and (e) The implications of trust issues in the provision of culturally sensitive and compassionate care to African American women with BCRLE by healthcare professionals. These findings can be used to guide related research and clinical interventions. Research outcomes can enhance clinicians' understanding of the diverse (and in some cases similar) influence that BCRLE has on African American women.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Strengths of the present study include the focus on the lived experience of how African American women describe what it is like to live with BCRLE. Descriptions from African American women included perceptions of the physical and emotional effects of changes in body/self-image, emotional and functional challenges presented in coping with the chronic and recurrent exacerbation of symptoms, adaptation and lifestyle changes, as well as, interpersonal relationships with healthcare providers. The opportunity to study African American women with BCRLE provides a unique perspective of this patient population. The findings from this study will help advance culturally-sensitive interventions for African American women with BCRLE that focus on psychosocial, psychological, psychosexual, and physiological dynamics. The discoveries of this study will enhance understanding of how this patient population copes with the distress of this condition and the long-term effects of BCRLE on the survivorship of African American women.

Other strengths included the application of rigorous qualitative phenomenological research methodology that guided data collection (i.e., use of a semi-structured interview guide derived findings from the extant literature), member checks including the corroboration of information with each participant during a second interview, and analysis of data (i.e., review of transcript coding by other health professionals). A limitation of this study the sample was limited primarily to middle-aged to older African American women from an urban cancer medical center. The findings may not be generalizable to all African American women in other settings. In addition, variations and differences in perceptions of the lived experience of breast cancer-related lymphedema may not have been entirely reflected during the two brief interviews sessions. Similar to other women who received cancer treatment [26] some women may not have felt comfortable talking about sexuality and body image issues dealing with their BCRLE, which may have limited what they openly discussed.

Implications for Nursing Practice

Nurses who care for African American breast cancer survivors need to understand how African American women perceived the effects of BCRLE and be prepared to routinely assess them for the presence of comorbid conditions and the effects of the physical, psychosocial, and psychosexual aspects of BCRLE. An informed awareness of patients experiences in living with BCRLE is necessary to develop adequate assessment and supportive interventions for these women. As patient advocates, nurses need to be aware and understand issues of trust and distrust of heathcare providers among African American women with BCRLE in order to foster positive adaptation including trustful relationships with healthcare providers. Culturally-sensitive interventions for African American women with BCRLE that focus on psychosocial, psychological and physiological dynamics would enhance understanding of how this patient population copes with the distress of this condition. This understanding is crucial to enhancing their quality of life.

Conclusions

BCRLE is clearly a chronic condition which negatively affects the quality of life of women. To capture real-life experience coping practices, healthcare providers should include the development of wide-ranging assessments of psychological and psychosocial statuses obtained thorough medical histories. Historical evaluations should include aspects of preexisting problems with substance abuse, mental health, coping strategies of positive appraisal and seeking social support as these may be important factors in how African American women cope with BCRLE. Through knowledgeable, attentive and empathetic assessment, oncology nurses and other healthcare providers can promote positive adaptive coping techniques among African American women with breast cancer-related lymphedema. It is important for all healthcare providers to be vigilant regarding feelings of misunderstanding, separation, fear and resentment that patients may be express. Women in this discussion have described sentiments such as these when speaking of issues contributing to the perceptions of distrust and trust of healthcare providers.

With the lack of literature on the explicit experiences and perceptions of African American women living with breast cancer-related lymphedema, this study provides a foundation for better understanding factors that influence perceptions in this patient population. Findings from this study support the assertion that a holistic and culturally relevant approach is needed to adequately assess the perceptions of African American women in the following areas: (a) How the visibility of BCRLE made having an illness harder to conceal. Thus BCRLE made a private condition more apparent, (b) How the effects of the tenacious, unpredictable and recurrent symptoms of BCRLE impact daily functioning in African American women with BCRLE, (c) The influence of BCRLE on African American women's perception of their self-image, (d) The importance of faith and family as key support systems used in the coping technique by African American women with BCRLE, and (e) The implications of trust issues in the provision of culturally sensitive and compassionate care to African American women with BCRLE by healthcare professionals. All of these findings can be used to guide related research and clinical interventions. Research outcomes can enhance clinicians' understanding of the diverse (and in some cases similar) influence that BCRLE has on African American women. The findings may also be useful to assist investigators from diverse theoretical perspectives to identify future research questions that can use a grounded theory approach to develop a theory of living with BCRLE.

Historically, research has used BCRLE samples comprised almost exclusively of married and well-educated Caucasian women. Stage of disease at diagnosis and treatment may differ between African American women and Caucasian women for several reasons. First, more African American women are participating in mammography screening, although they may not have access to appropriate follow-up treatment [27,28]. Caucasian BCS tend to use formal support groups to help cope with BCRL. However, African American women are less likely to attend formal support groups due to lack of culturally sensitive topics and issues. Finally, as compared with Caucasians more African American women are diagnosed with more advanced stages of breast cancer [13,28].

Nursing's social policy statement (American Nurses Association, 2003) and the American Cancer Society [29,30] indicated that nursing practice is characterized by attention to the full range of human experience and integration of knowledge gained from understanding of patients' subjective experiences. "Nurses' ability to care for patients is predicated on shared understanding about the meaning of illness and treatment and the effect of experience on identity and ongoing life" [31]. This statement emphasized the need for nurses to understand the subjective experiences of all women including African American women with BCRLE and be prepared to address common adaptation problems in their practice. This study also illuminated the importance of identifying effective strategies for assessing patients' psychosocial dispositions, coping strategies including avoidance. Additionally, an informed awareness of patients experiences in living with BCRLE is necessary to develop adequate assessment and supportive interventions for these women. Furthermore, the perception of improved care is the patient's expression of satisfaction with their care which also fosters positive adaptation including trustful relationships with healthcare providers.

The stories as told by the African American women captured the essence or true meaning of their experiences. Knowledge was gained to better understand how African American women perceived the effects of BCRLE from the viewpoint of the participants. The findings described the effects of the physical, psychosocial, and psychosexual aspects of BCRLE and issues of trust and distrust of heath care providers among African American women with BCRLE.

References

- Palmer NR, Weaver KE, Hauser SP, et al. (2015) Disparities in barriers to follow-up care between African American and White breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 23: 3201-3209.

- Karcher R, Fitzpatrick DC, Leonard DJ, et al. (2014) A Community-based Collaborative Approach to Improve Breast Cancer Screening in Underserved African American Women. J Cancer Educ 29: 482-487.

- American Cancer Society (2015) Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts and Figures 2014-2015. Atlanta, GA.: American Cancer Society.

- Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Kidd N (2011) Breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema self-care: Education practices, symptoms, and quality of life. Support Care Cancer 19: 631-637.

- Ridner SH, Sinclair V, Deng J, et al. (2012) Breast Cancer Survivors With Lymphedema: Glimpses of Their Daily Lives. Clin J Oncol Nurs 16: 609-614.

- Armer JM (2005) The problem of post-breast cancer lymphedema: Impact and measurement issues. Cancer Invest 23: 76-83.

- Aziz NM (2002) Cancer survivorship research: Challenge and opportunity. J Nutr 132: 3494S-3503S.

- Kwan ML, Darbinian J, Schmitz KH, et al. (2010) Risk Factors for Lymphedema in a Prospective Breast Cancer survivorship study. The Pathways Study. Arch Surg 145: 1055-1063.

- Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry LN, et al. (2015) American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. J Clin Oncol 34: 611-635.

- Meeske KA, Sullivan-Halley J, Smith AW, et al. (2009) Risk factors for arm Lymphedema following breast cancer diagnosis in Black women and White Women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 113: 383-391.

- Bourjolly JN, Hirschman KB (2001) Similarities in coping strategies but differences in sources of support among African American and White women coping with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 19: 17-38.

- Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, et al. (2002) Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: Comparing African Americans, Hispanics, and Non-Hispanic Whites. Psychooncology 11: 495-450.

- Radina ME, Armer JM, Culbertson SD, et al. (2004) Post-breast cancer lymphedema: understanding women's knowledge of their condition. Oncol Nurs Forum 31: 97-104.

- Yoon J, Malin JL, Tisnado DM, et al. (2008) Symptoms after breast cancer treatment: are they influenced by patient characteristics? Breast Cancer Res Treat 108: 153-165.

- Ridner SH, Dietrich MS (2008) Self-Reported Comorbid Conditions and Medication Usage in Breast Cancer Survivors With an Without Lymphedema. Oncol Nurs Forum 35: 57-63.

- Bowman KF, Deimling GT, Smerglia V, et al. (2003) Appraisal of the cancer experience by older long-term survivors. Psychooncology 12: 226-238.

- Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, et al. (2005) Post-Treatment Symptoms Among Ethnic Minority Breast Cancer Survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 32: 250-254.

- Joslyn SA (2002) Racial differences in treatment and survival from early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer 95: 1759-1766.

- McWayne J, Heiney SP (2005) Psychologic and Social Sequelae of Secondary Lymphedema. Cancer 104: 457-466.

- Sandelowski M (1998) Writing a good read: Strategies for re-presenting qualitative data. Res Nurs Health 21: 375-382.

- Collins-Bohler D (2012) The Lived Experience Of African American Women With Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 644.

- Strauss A, Corbin J (1990) Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 1600 Clifton Rd. Atlanta, GA 30333, USA.

- Barg FK, Gullatte MM (2001) Cancer support groups: Meeting the needs of African Americans with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 17: 171-178.

- Jacobs EA, Rolle I, Ferrans CE, et al. (2006) Understanding African Americans' Views of the Trustworthiness of Physicians. J Gen Intern Med 21: 642-647.

- Sacerdoti RC, Lagana' L, Koopman C (2010) Altered Sexuality and Body Image after Gynecological Cancer Treatment: How Can Psychologists Help? Prof Psychol Res Pr 41: 533-540.

- Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, et al. (2006) Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med 144: 541-553.

- Coward DD (1999) Lymphedema prevention and management knowledge in women treated for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 26: 1047-1053.

- American Cancer Society (2006) Lymphedema: Understanding and managing lymphedema after cancer treatment. Atlanta: American Cancer Society.

- American Cancer Society (2007) Global Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society, Atlanta., GA: American Cancer Society.

- Rosedale M (2009) Survivor Loneliness of Women Following Breast Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 36: 175-183.

Corresponding Author

Deborah Collins-Bohler, PhD, CG, MSN, RN, Associate Professor, School of Nursing, Eastern Michigan University, 366 Marshall Building, Ypsilanti Mich., 48197, Michigan, USA, Tel: 313-4053757, Fax: 734-4876946.

Copyright

© 2019 Collins-Bohler D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.